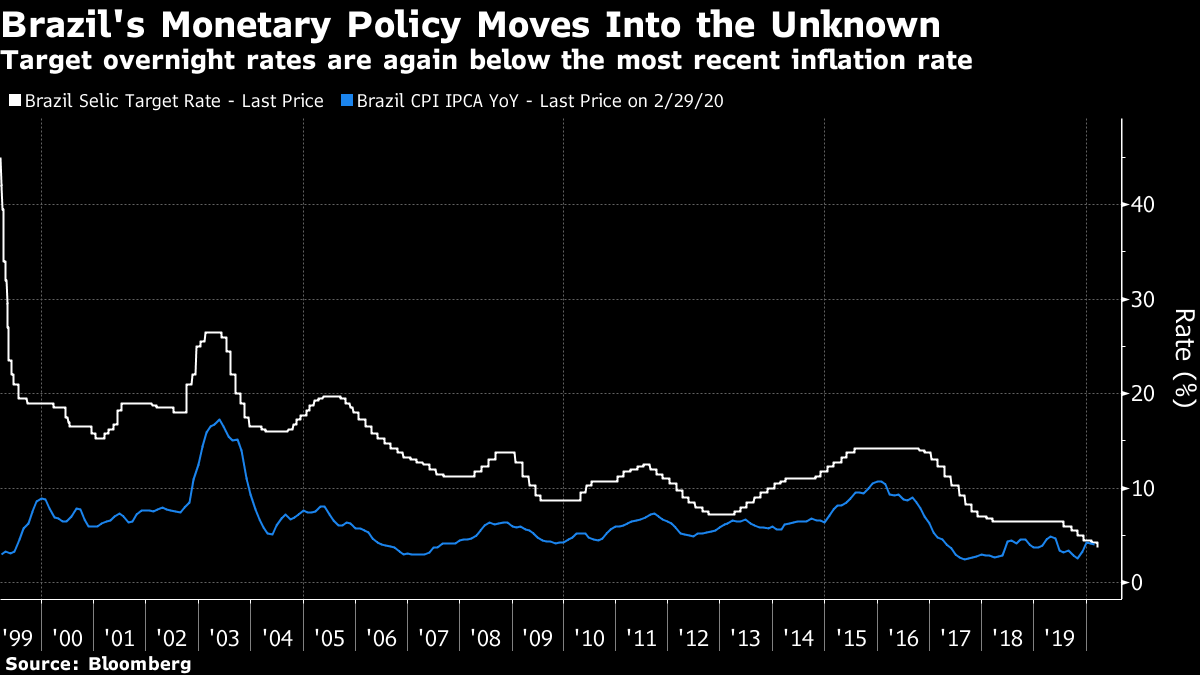

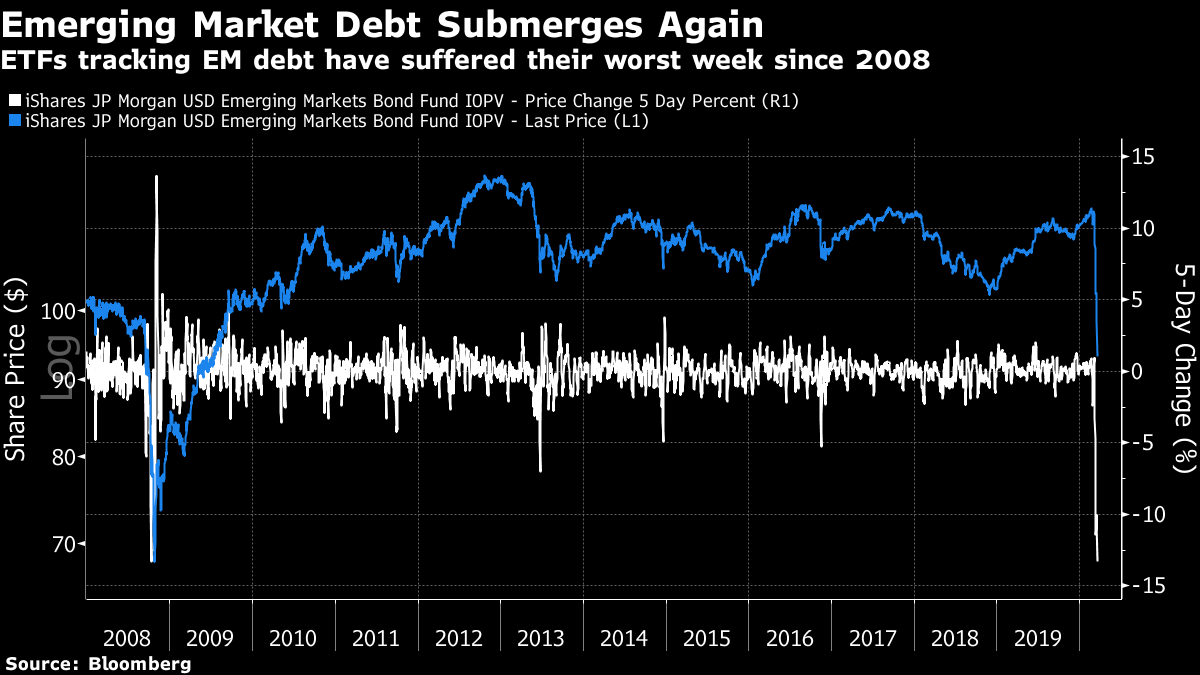

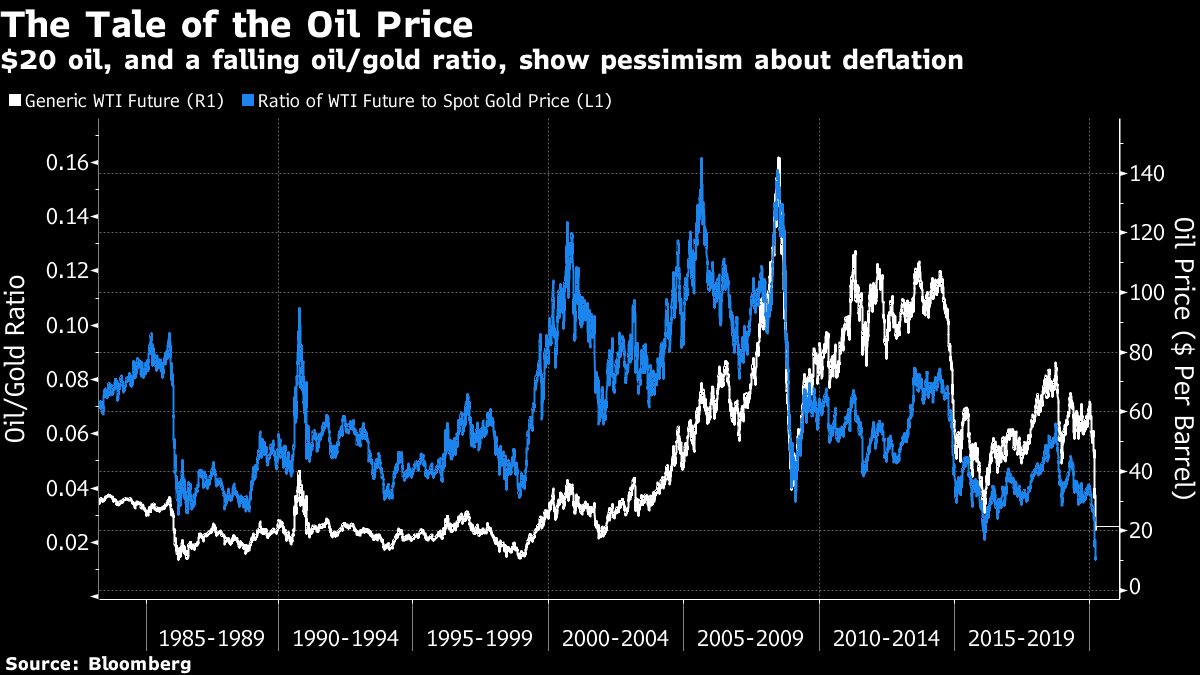

| On one thing it seems that everyone agrees. The world has changed in the last two months, and by the time the pandemic subsides, it will have changed utterly. The Archbishop of Canterbury (who started his career as an oil executive before going into the church), has likened the impact to a nuclear explosion — "the initial impact is colossal but the fallout last for years and will shape us in ways we can't even begin to predict at the moment." He was talking about the impact on society, but his analogy also works perfectly for the effect the virus is having on the financial world. It has already forced profound changes and extreme reactions. The final state is going to be very different from the current one; but it remains opaque what that final state could be. Perhaps the single biggest policy move of the last 24 hours came when the European Central Bank announced its latest package. To use the phrase beloved of central banks, it was an attempt at a "big bazooka" while the new president, Christine Lagarde, attempted to rectify her mistake of last week by stating that there were "no limits" on what the ECB would do. Last Thursday's attempt to deny that it was part of her job to close the spreads between peripheral and core bond yields can now be erased. Instead, to borrow the phraseology of Deutsche Bank AG's chief U.S. economist Torsten Slok, she is now at last making good on her predecessor Mario Draghi's promise to do "whatever it takes" to save the euro. It was always remarkable that the market never tested him to see whether he would make good on that pledge. Now his successor must do the job. The main headline is that the ECB has announced it is ready to expand its balance sheet by another 750 billion euros ($820 billion), which it can spend on securities. The kind of securities, and the timing of the purchases, are completely up to the bank — it has given itself great flexibility. It means that the ECB balance sheet, which has stabilized over the last two years, will increase another 16%:  There is every chance these measures will work, but only to solve a problem that now seems rather a narrow one: The transmission mechanism for monetary policy is no longer working within the euro zone, and interest rate moves by central banks aren't promptly feeding through into other borrowing costs within the economy. Lagarde and her colleagues have now given themselves the tools to, as Slok puts it, "make sure that monetary policy is functioning both in the north and south of the euro zone." To quote Draghi once more: "Believe me, it will be enough." The problem is that far more than monetary policy is needed. Nothing Lagarde announced will help any companies to open for business, boost their revenues or pay their staff. That instead depends on public health authorities containing the virus, while fiscal policy will be needed to mitigate the effects of whatever measures are taken to achieve that goal. Across the world, there is the sense of central banks doing all that they can, reaching the end of the road, and handing over to politicians to craft a fiscal response. In many cases they are doing so in the teeth of a severe financial crisis that will make it far harder to come up with the measures needed to coax the economy through the pandemic. For example, in other circumstances, the decision by Brazil's central bank to cut its own target overnight rate by 50 basis points, having previously said it was done with cutting, would have been major news. In historical context, this is extraordinary. The Selic rate is now below the most recent inflation rate. A country that for generations has been preoccupied by inflation, and can easily remember hyperinflation, has joined the club of nations worried about stagnation:  Those worries are alive despite the effects of an old-fashioned run on emerging market and particularly Latin American currencies that would usually raise the risk of importing inflation. The dynamics of this currency run have nothing to do with the pandemic, and everything to do with the financial crisis it has created. To date, Brazil has only suffered two coronavirus deaths, according to Johns Hopkins. Mexico has suffered none. And yet both have seen their currencies drop to all-time lows against the dollar.  Emerging market debt has also subsided into a crisis almost as severe as the one that struck it after Lehman. This also involves intense pressure on corporates and state-owned enterprises, particularly in petroleum-producing nations.  The pressure on nations reliant on commodities isn't letting up, and may even be exacerbated by the ECB's move as it should tend to weaken the euro and make buying dollars more appealing. The Australian dollar, currency of a "lucky country" that has gone almost three decades without a recession, fell to its lowest since 2002 after the ECB announcement:  That pressure comes from the pandemic, but also from the oil price shock prompted by competition between the major producers at the beginning of this month. That price war has mixed with the deflationary fears that the virus has aroused to bring oil prices down to levels once scarcely imaginable. West Texas Intermediate bounced having dropped below $21 per barrel, while the ratio of oil to gold continued to fall to historic lows. That implies deep pessimism about deflation, which monetary policy may not be able to deal with:  In the face of all these concerns, the focus is now firmly on the governmental response. The U.S. Senate voted a round of coronavirus aid on Wednesday, and much more is likely to come, with the administration setting its sights on mailing checks out to Americans — ideally within two weeks. In Europe, German Chancellor Angela Merkel made a rare televised address. The chances of unthinkables such as Germany deciding to increase its deficit, and consenting to some unified borrowing and fiscal policy across the euro zone have suddenly risen. The problem, as Slok pointed out, is that sending checks to people takes much more time than cutting an overnight interest rate. Even once agreed by all the necessary politicians, recent exercises in disbursing money directly have taken months, rather than weeks. As this is a profoundly new direction for policy, lawmakers on both sides of the Atlantic could be excused for wanting to take some time to discuss the precedents they are setting. But time isn't on their side. Many companies are making no revenue, and will need to close their doors and lay off staff unless aid reaches them quickly. Slok offered this back-of-the-envelope arithmetic. U.S. gross domestic product is $20 trillion in round numbers, of which 70%, again in round numbers, comes from consumption. That means that consumers contribute a bit less than $1.2 trillion each month. So if the nation comes to a complete halt and stays that way for three months, the implication is that it will take a bite approaching $4 trillion out of GDP. So a fiscal package of $4 trillion might be in order. Or even more if the lockdown carries on longer. Less if the pandemic comes under control earlier. What remains certain is that the first installments are needed quicker than fiscal policy can usually arrive. Let's return to the archbishop's analogy. Following the explosion, we can already see that the long-term fallout will be profound. With desperate urgency and little debate, the world is resorting to helicopter money — creating money and spending it. Faced with the pandemic, the state is expanding and few are resisting. I commented a week ago — although it seems much longer than that now — that a new financial order was needed, with a break as clear as the one that followed Nixon ending the Bretton Woods tie between the dollar and gold in 1971. At least in the first instance, it looks like the immediate shift will be similar to the one that Nixon ushered in. Governments will take a greater role, and spend far more freely. We know how that worked in the 1970s, so this version of the new order may not last long. But at this point, it seems hard to avoid moving into a new age of fiscal expansion, for the first time since the 1970s. As for the longer term, as the archbishop said, the explosion will shape us in ways we can't even begin to predict. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment