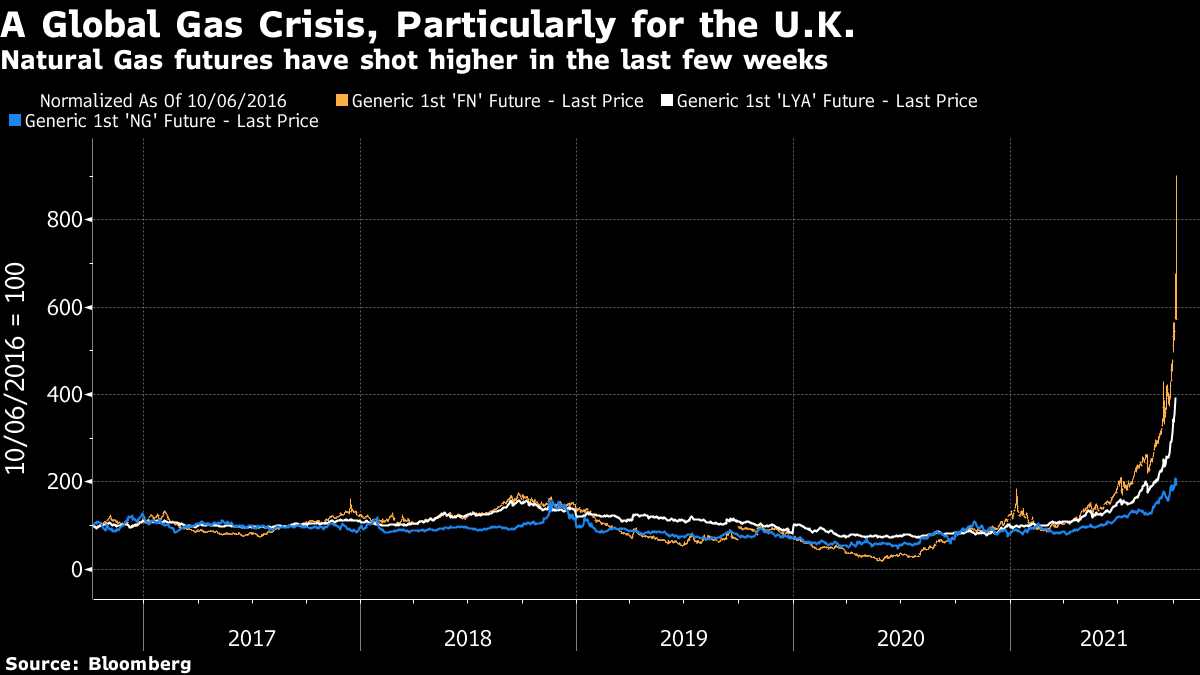

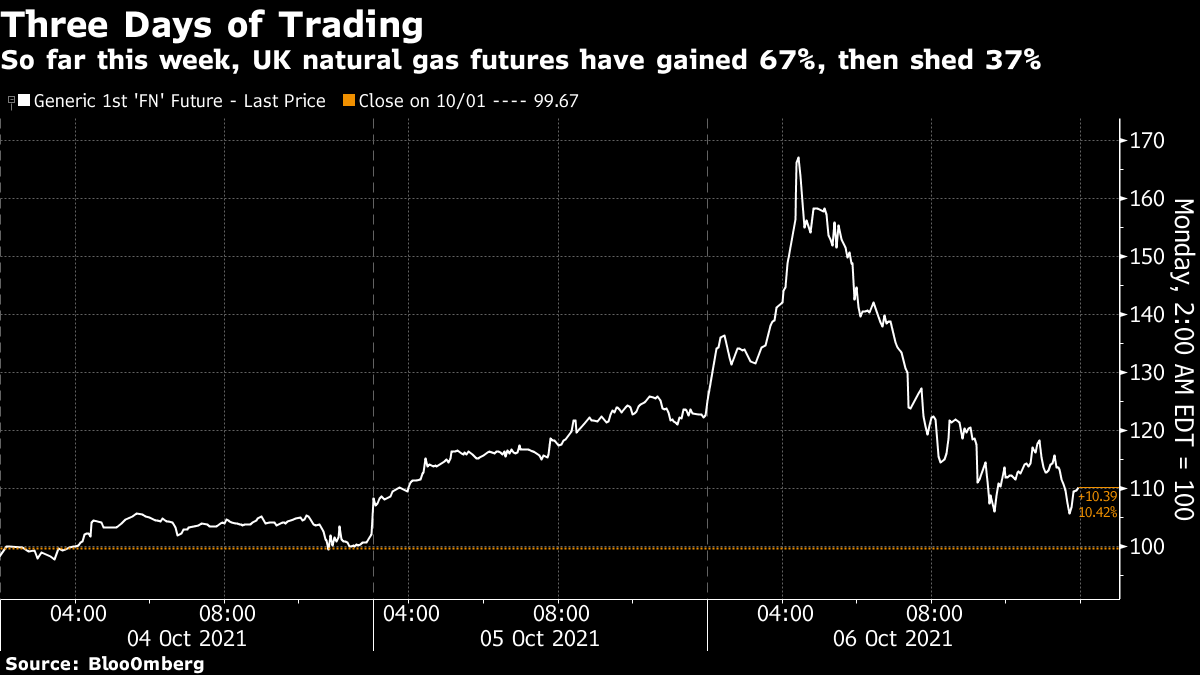

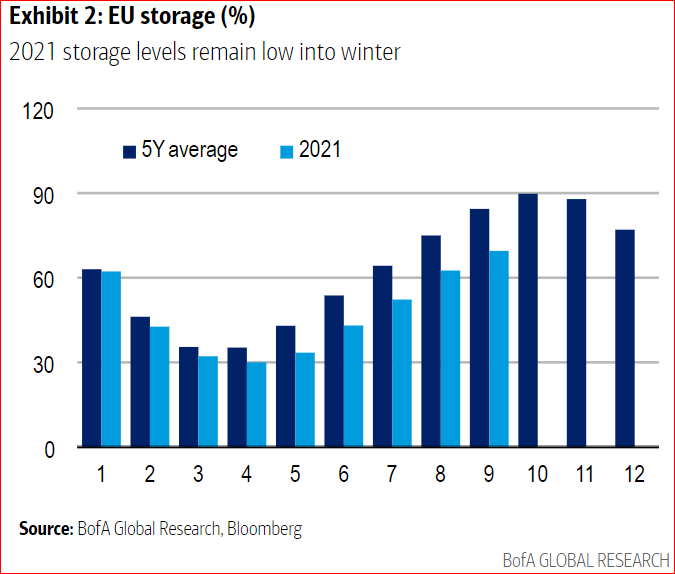

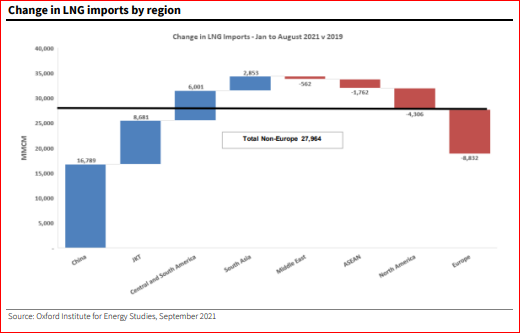

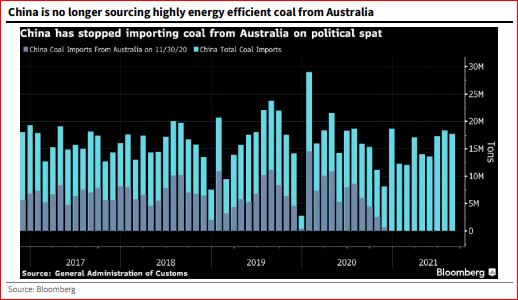

| What is happening in the natural gas markets is extraordinary, and it could create serious human hardship. On that we can all agree. Here is how natural gas futures in the U.K. (FN on the chart), Germany (LYA) and the U.S. (NG) have moved over the last five years:  And here is how U.K. natural gas futures moved in the first three days of this week:  Such things don't happen often. And while natural gas has seen the most extreme moves, the trend of suddenly rising energy prices goes further. This is how Europe's most widely traded forward contract for coal has traded since the beginning of the financial crisis 14 years ago:  Two questions now matter. First, how did this happen (and therefore, how might the situation be resolved)? And second, what could be the contagion effects for the economy and for global markets? What Happened? The answer has surprisingly little to do with the pandemic, and in Britain (as the problems elsewhere make clear), Brexit has been little more than an aggravating factor. One part of the problem is that the EU (and the U.K.) did a poor job of storing gas in advance, as this chart from BofA Securities Inc. shows:  Europeans also seem to have been blindsided by increased demand from Asia, particularly China. Over the first eight months of this year, total imports of liquid natural gas were far higher in non-European countries than in the first eight months of 2019. Imports by North America and Europe fell:  In part this was a byproduct of another geopolitical skirmish. China stopped importing coal from Australia last year as punishment for its call for an international investigation into the origins of Covid-19. As this chart from BofA shows, this forced them to step up imports from everyone else:  Beyond this, the climate issue arises in two ways. First, as has always been the case, demand for heating fuel tends to rise when people grow worried there will be a cold winter. Climate change and a succession of freak weather events have amped up concern. Second, there is the attempt to "de-carbonize" and move from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. The problem is to make sure that sufficient carbon-rich energy remains available until renewables are able to pick up the load. That hasn't happened. Finally, what has happened looks worryingly like another example of belief that markets could be relied on both to reduce prices for consumers and to police themselves. As was discovered during the financial crisis, this wasn't a great assumption. Numerous different suppliers can now offer energy in the U.K., but Sir Dieter Helm, professor of energy policy at Oxford University, this week offered a withering assessment of the way energy had been opened to market discipline: [I]t is remarkable that any supplier could hold a licence whilst being unable to meet its contractual obligations with customers under the price cap in the event of commodity price rises. There has been a big regulatory failure, and behind this lies the core issue of the reliance on spot real-time pricing and the relative absence of long-term contracts. This bears a remarkable resemblance to the failure of Northern Rock [a U.K. home lender which collapsed in 2007], which relied on spot market funding. The socialised cost of supplier failures may cost over £1 billion. The state – in the guise of the regulator – has to step in to make all customers pay. So much for the one-way bet of supplier competition.

Finally, there is the issue of Russia's role as a gas exporter to Europe. This could be held to involve malign or Machiavellian behavior by a country keen to isolate Ukraine and supply Germany through the controversial Nord Stream 2 pipeline. But as Helm pointed out, the problem runs deeper, and involves policy mistakes in western Europe. As Helm put it: Russia is the first immediate cause of the current gas crisis. Russia claims that it is fulfilling all its gas contracts. Presumably it could add some spot gas too, and especially at these prices… Did nobody see what was going on, as storage in Europe remained unfilled, the German election approached, and Biden engaged with the Ukrainian government? The Russian motivations surrounding Nord Stream 2 have always been in plain daylight for all to see. There have been repeated attempts to manipulate supplies through Ukraine since Putin came to power, and the Nord Stream pipelines have all the hallmarks of a Russian–German project bypassing the Baltic States and Poland, and deliberately isolating Ukraine. The EU failed to centralise its buyer bargaining power, as Donald Tusk once proposed, and allowed Russia to divide up the market and exploit its market power. Nothing unpredictable about all this.

For further evidence that this crisis is above all about Russia, Wednesday's market turn and the sudden fall in gas futures came after Vladimir Putin voiced some willingness to help. This is what he said, as translated by the Financial Times: "Let's think through possibly increasing supply in the market, only we need to do it carefully. Settle with Gazprom and talk it over," Putin said. "This speculative craze doesn't do us any good."

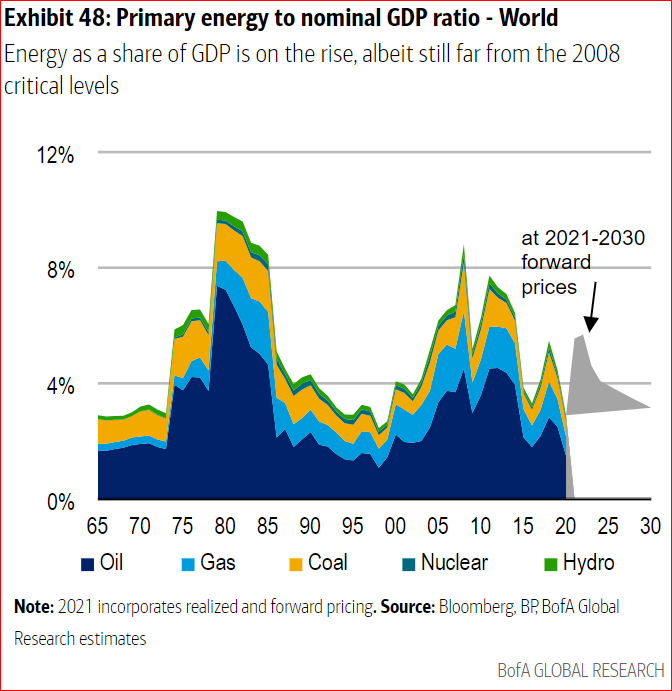

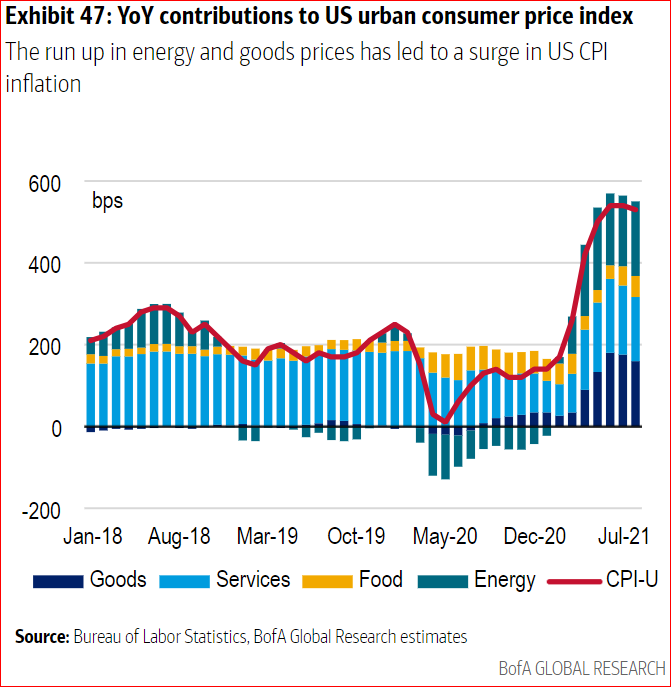

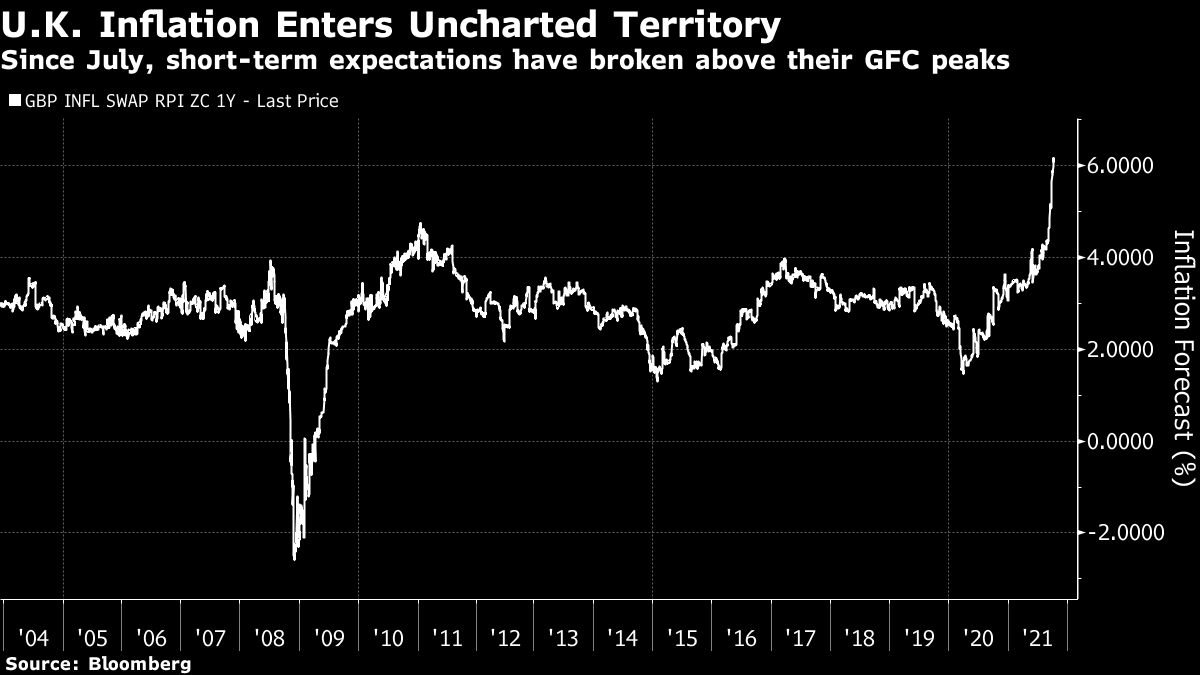

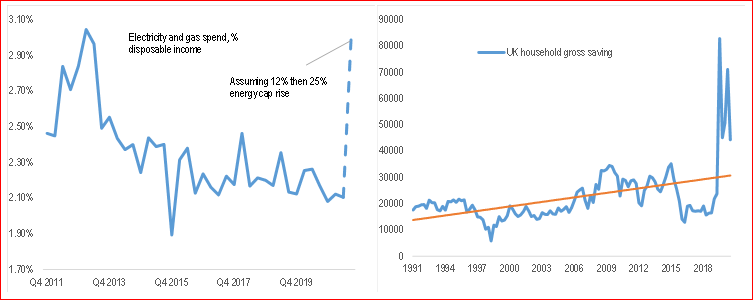

That's true, but he could have done this a while ago, and he is offering no specifics. The strength of the market reaction showed both that the previous rise had become extreme, and that traders genuinely feared Russia would do nothing to ease the crisis. There is a decent chance that Putin has marked the top, but prices remain extreme, and more progress is needed. What Happens Next? What of financial contagion? Any moves on this scale might have inflicted losses on some funds that could lead to forced sales. There is no evidence of this so far, but there can always be domino effects when investors are taken seriously by surprise. The risks of economic contagion are more immediate. If this is allowed to lead to power outages, that will take a direct bite out the economy, much as last year's Covid shutdown did. Beyond that, higher fuel prices can displace other economic activity. The 2008 oil spike brought the concept of the "oil burden" — the share that energy expenditure took out of global GDP. The 1973 surge inflicted much more damage because at that point the global economy was much more "oil-intense." Now, with services predominant and energy use generally more efficient, paying for oil is less of a drag. As the following chart from BofA shows, even current prices imply energy is barely half its weight at the end of the 1970s. Higher prices for fossil fuels are still bad news for the economy in the short term, and power cuts would also inflict great damage. But as it stands, the economic hit from the natural gas crisis isn't enough to tip Europe or anywhere else into recession:  More significant is the indirect impact via inflation. Much of the rise in U.S. inflation this year can be attributed to fuel price increases. These should be, to use the word of the moment, "transitory." A renewed bout of rising energy prices helps keep inflation higher for longer, and raises the risk that employees demand higher wages to compensate. And of course higher inflation, all else equal, increases the risk that central banks will raise interest rates. That crimps economic activity:  Within the U.K., particularly exposed to the problem, the gas crisis has fed into a startling rise in market-based inflation expectations, which make it all the harder for the Bank of England to avoid taking action:  Looking at calculations for a U.K.-specific "oil burden", there is a clear danger that price increases could take a full percentage point out of disposable incomes. That sounds like a recipe for 1970s-style stagflation. However, as this chart from Credit Suisse Group AG illustrates, pandemic after-effects mitigate this to an extent. British households have a lot of money saved up. They'd doubtless prefer not to spend any of it on higher fuel bills, but this does limit the potential economic damage:  In short, this is a dangerous crisis, but need not be as serious as the recurring energy crises of the 1970s. The greatest risk is that it will force up inflation, and force tighter money from central banks. My colleague Mark Gongloff has been writing about "idiot plots." The great movie critic Roger Ebert coined the phrase to describe "any plot that would be resolved in five minutes if everyone in the story were not an idiot." It's harsh to call the natural gas crisis an idiot plot, but it has elements. It's happened in large part because a lot of people have behaved like idiots, and Putin has treated them accordingly. For a true idiot plot, Mark suggests the latest furor over the U.S. debt ceiling. For historical reasons, the U.S. has a fixed amount of debt that the government is allowed to take on, and needs congressional approval to raise it. This has happened dozens of times, and the ceiling hasn't stopped politicians from both parties making spending commitments that can only be met by borrowing more than the limit. If Uncle Sam were to default, the consequences for the global financial system are hard to imagine. It would be a disaster, caused solely by Congress. Everyone has an interest in avoiding a default. You would think that the debt ceiling (which doesn't exist in any other major economy) could only become the center of a crisis if everyone involved were an idiot. Politicians might threaten not to raise the limit to give themselves some leverage, but to go through with such a thing would be insanity. Mitch McConnell, the Republican minority leader in the Senate, isn't an idiot, and he isn't insane, but it appears that markets truly feared he might be. Early Wednesday afternoon he made a statement that signaled a potential end to the crisis. Like Putin's, his comments were disingenuous in the extreme: "To protect the American people from a near-term Democrat-created crisis, we will also allow Democrats to use normal procedures to pass an emergency debt limit extension at a fixed dollar amount to cover current spending levels into December"

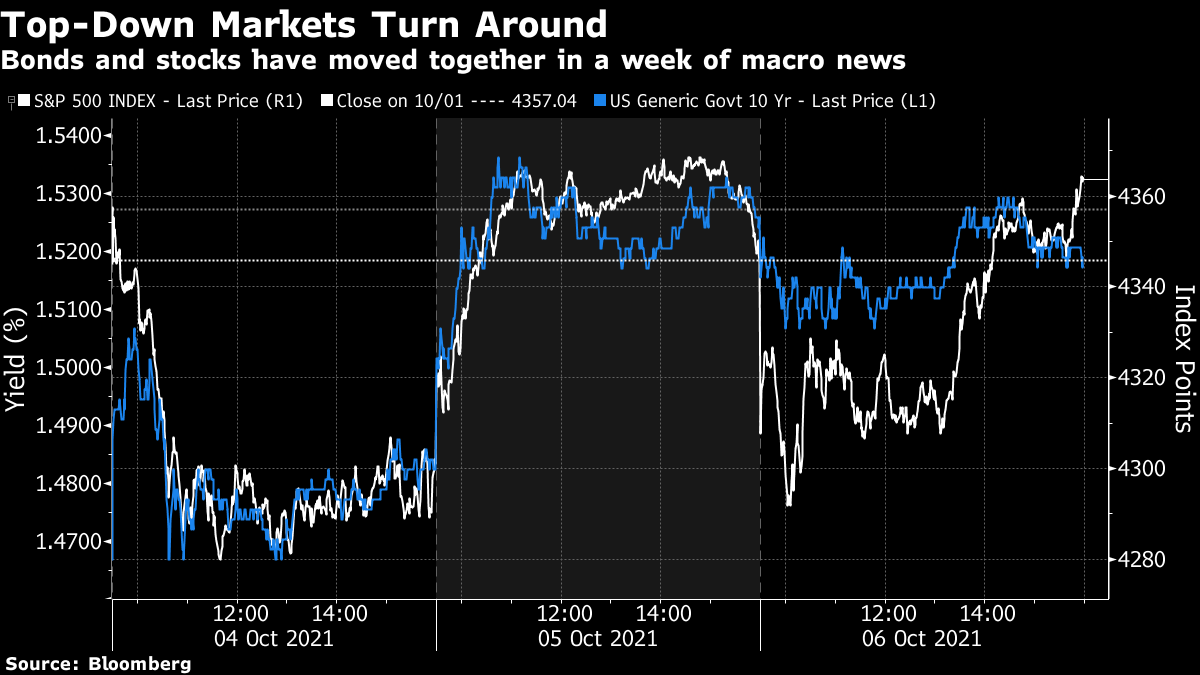

It's true that the Democrats played their full part in increasing spending. It's also true that the big tax cut McConnell shepherded through Congress four years ago had a huge role in creating the need for more borrowing — and that there would have been no crisis if he hadn't refused to raise the debt ceiling. Machiavellian behavior by politicians is to be expected in today's febrile environment but it's no less distasteful for that. Also, note that all McConnell has really done is give the Democrats two more months. If anything, you could argue that his statement prolongs the agony. The comments prompted a dramatic afternoon surge in markets, showing just how much traders had grown to worry that everyone on Capitol Hill was indeed an idiot:  The way that equities and bond yields have moved together shows that the markets are rigorously "top down" at present. It is macro and political developments that move prices. And the tale of Wednesday's tape said something profound about lack of trust. Gas markets and U.S. stock and bond markets reacted with joy to comments by Putin and McConnell that did no more than suggest they might help avert an almost unthinkable crisis that they themselves largely caused.  | Happiness is… watching your team beat their biggest rivals and end their season. It happened Tuesday night, as the Boston Red Sox beat the New York Yankees. What was greatest was seeing Yankee presumptions come to grief. Watch this video. In it, the fearsome Yankee slugger Giancarlo Stanton whacks the ball a long way, and it bounces high off the big green wall known as the "Green Monster." Stanton thinks he has hit a home run, pauses to admire it, and as a result only gets as far as first base, when he should easily have made it to second. John Sterling, the Yankees' veteran radio commentator, is so convinced that the ball is leaving the park that he launches into a home run call, tells his unfortunate listeners that it was a "Stantonian home run," and only then notices that somehow it was only a single. Commentators and hitters alike should check their presumptions. Otherwise fans of their rival teams will enjoy great mirth at their expense. They might even watch videos of your presumptuousness with mounting glee hundreds of times on repeat. That's a survival tip. And try listening to John Fogerty's Centerfield, a great baseball song that many rightly said I should have listed yesterday, Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment