| "The basic problem," I once wrote, "is that, if you are a senior executive at a public company, you always know stuff about your company that the public doesn't know, but you might want to sell stock sometimes." This is a real and hard problem. If you are the chief executive officer of a public company, every single minute of every day you know more about that company than the average retail investor does. If the standard was "you can never sell stock if you know anything the public doesn't know," you could never sell stock. Maybe that's fine! Maybe the rule should be "nobody who works for a public company can buy or sell stock in that company until they leave the company." But that does seem like a harsh rule. Companies like to pay senior executives in stock, to align incentives, and they like the executives to hold that stock for a long time, but they also want the executives to be able to buy houses and pay for their kids' college tuition and if all goes well buy yachts. If the rule was "stock can never be sold," companies would have to pay their executives with more cash and less stock, and executives who had liquidity problems would have to quit to be able to sell their stocks. You could imagine other clean, simple rules, but they all seem bad. "Executives are not allowed to own stock in the company they work for" would be a weird one. "Executives are not allowed to learn any nonpublic information about the company they work for" would be even weirder. "Insider trading is legal, executives can trade their company's stock whenever they want and make use of inside information, it is just another form of compensation for executives" has a real appeal in certain circles, and seems to have been the de facto rule in the U.S. a century ago, but is very much out of the mainstream right now. So what we have, in the U.S., is a rule that is essentially "corporate executives can trade their company's stock, but not if they have any material nonpublic information about the company." At some level this rule is nonsense: The executives always know something that public investors wish they knew; there is no meaningful standard for what information is "material" (and so illegal to trade with) and what is just, you know, relevant to making informed decisions about the stock. But we muddle through and it is, eh, mostly fine-ish. There are some simple crude quasi-rules to implement this theoretically rickety system. For instance: - If an executive sells stock after she finds out about some huge disaster at the company, but before the company announces the disaster publicly, she will get in trouble for insider trading, or at least get a lot of mean articles written about her.

- Similarly if she buys stock right before announcing good news, though people generally seem less fussed about this one.

- Most companies have "blackout periods," when executives are presumed to have lots of material nonpublic information and are not allowed to trade, and "open windows," when all of the information about the company is presumed to be public and the executives are allowed to trade. What this means in practice is that, for a few weeks after a company announces its quarterly earnings, executives are presumed not to know any more about the company than the public does, and they are allowed to trade. This is not true — obviously they still know more about the company than the public does! — but it is a widely accepted convention. When the earnings come out, the public is reasonably up to date with all the material stuff.

- Executives can use 10b5-1 plans to automatically sell their stock. If you have a baby, you can plan to sell a bunch of stock in 18 years to pay for the baby's college. You enter a binding agreement with your broker to say "in 18 years sell $100,000 worth of stock" or whatever, and then forget about it. In 18 years, you sell the stock automatically, and obviously you did not have any inside information; it's been 18 years since you made the trading decision. Of course I am kidding; nobody sets up 10b5-1 plans 18 years in advance. At the end of the year you think about your expenses for next year, and you think about what you think the stock will do, and then you tell your broker, like, "if the stock doubles sell a lot of it, and if it stays flat sell a little, and if it goes down just hang onto it," or vice versa or whatever. And obviously your 10b5-1 decisions will be informed at least a little bit by what you know about the company and what you expect the stock to do. And there are various ways that 10b5-1 plans can be gamed. Still, we muddle through.

Anyway here's a Bloomberg Businessweek story about how corporate executives trade their companies' stocks and know more than the public: Purchases made by U.S. executives outperformed the S&P 500 over the ensuing 12 months by an average of five percentage points between 2015 and 2020, according to a TipRanks analysis. The gap might seem scandalous to those with only a passing acquaintance with U.S. insider trading rules, which make it illegal for insiders to trade using material—or financially significant—nonpublic information. And yet on Wall Street it's long been an open secret that insiders trade on what they know. … Insiders will always have a better general sense than others about how their company is doing. But a growing body of research suggests that many insiders are trading well thanks to something more than luck or judgment. It indicates that insider trading by executives is pervasive and that nobody—not the regulators, not the Department of Justice, not the companies themselves—is doing anything to stop it. "There is a lack of appreciation for the amount of opportunistic abuse that exists under the current system, the amount of egregiousness," says Daniel Taylor, a professor at the Wharton School and the head of the Wharton Forensic Analytics Lab. "Most Americans today believe the stock market is rigged, and they're right."

I don't know. I guess you could imagine stricter, clearer rules. The stuff I mentioned about blackout periods is sort of informal and driven by corporate policies; you could imagine Securities and Exchange Commission rules imposing blackout periods on corporate executives. You could imagine them being very strict. "Executives can only buy or sell stock one day per quarter, two weeks after earnings, in a public auction in which everyone knows exactly how many shares the executives are submitting for purchase or sale"? They might still know stuff that you don't, but at least you know, like, how badly they want to buy or sell the stock, and you can adjust your views accordingly? Still seems harsh to me, but I don't really think this is a big problem that needs a big solution. If you do think that, though, the thing to do is to think realistically about solutions, and the place to start from is that executives always know something that the public doesn't. You can't avoid that problem; a rule that says "an executive can only sell stock if she has no nonpublic information" doesn't really work. Last summer, Mark Zuckerberg was hauled before Congress to explain why Facebook Inc. is not a monopoly. He had a simple and elegant answer: We face a lot of competitors in every part of what we do, from connecting with friends privately to connecting with people in communities to connecting with all your friends at once to connecting with all kinds of user-generated content. … Congressman, the space of people connecting with other people is a very large space.

Facebook is not a monopoly because there are other ways to have human relationships with people. You can call them on the phone, or walk over to them and say hi, or there are various forms of physical endearment that people enjoy. Facebook competes with all of these things. Relatively little human interaction takes place on Facebook, compared to all of the other possible ways to interact with humans. If Facebook dramatically raised the price of interacting with other people on Facebook, maybe you'd meet them for dinner instead. In antitrust terms this is an argument of "market definition." Congress worried that Facebook is the dominant player in what Congress thinks is its market (online social media),[1] but Zuckerberg explained that it is just one small player in the market correctly understood ("people connecting with other people"). You don't have to agree with him! Arguably it's absurd, to say, no, we compete in the global market for people having any sort of interaction with each other, we're a tiny fraction of that market. But let's say you take him seriously. Fine fine fine, Facebook, you are not a monopoly. You are just a scrappy competitor fighting for market share in the interacting-with-humans business. But … uh … how are you doing that? How are you going to take market share from talking to people? It is nervous-making. I wrote at the time: When Facebook says "we're not a monopoly, there's lots of competition in the connecting-with-people space, some of our most fearsome competitors include Having Dinner With Friends and Reading Stories to Your Children," you could interpret that as a threat. Facebook is good at disposing of competitors! Maybe it will copy enough features from Reading Stories to Your Children so that people will abandon it for a Facebook product, Instagram Reads Stories to Your Children or whatever. Maybe it will acquire Having Dinner With Friends so it can merge it into the Facebook experience.

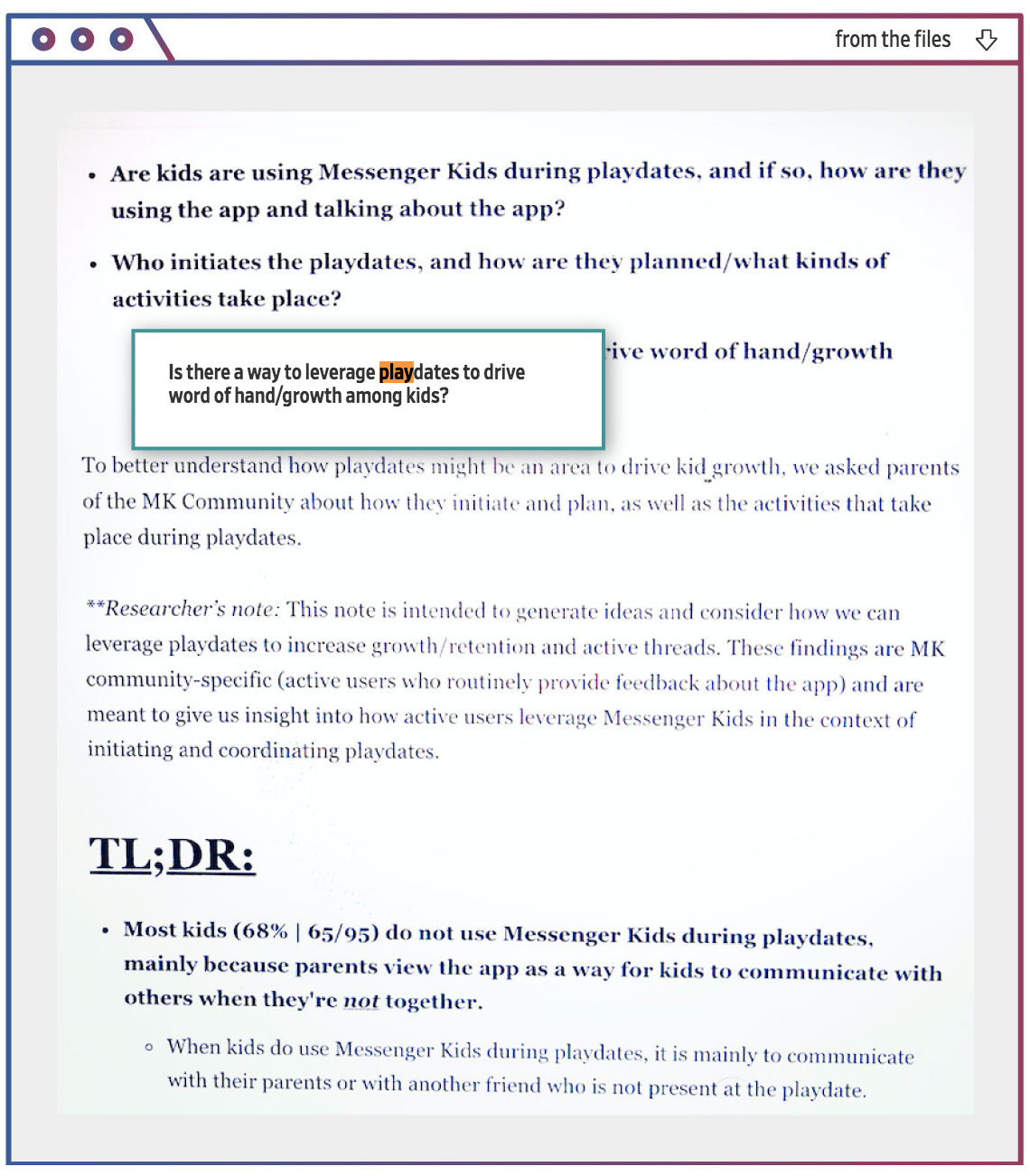

Honestly? If I do say so myself? I thought that was a pretty good joke. I patted myself on the back a little bit for that paragraph. Anyway today's Wall Street Journal has this page from an internal Facebook presentation about how to compete with children's playdates:  Yes! Right! The good news is that Facebook is still a relatively small player in the playdate space! It has only about a 32% market share in playdates! The bad news is that it works hard every day to disrupt Big Playdate and take over that market for itself! "Leverage playdates to increase growth/retention"! Great stuff. A common story about special purpose acquisition companies is that they are a good way for young speculative companies to go public, because if you go public by SPAC you can market your stock publicly based on projected future financials, while if you go public by a traditional initial public offering, you have to market your stock based only on historical financials. If you have never made any money, but hope to make a lot of money, the SPAC seems better. It's better marketing to say "we will have $100 billion of revenue in 2028" than "we have never had any revenue." This story is perhaps oversimplified — the legal regime is more complicated than that, and in practice traditional IPOs involve marketing based on projections, just not in the actual prospectus — but it is true enough. Intuitively you might assume something like the following: - The higher a SPAC's projected future revenue is, the more investors will want to buy its stock; and

- The higher a SPAC's projected future revenue is, the less likely it is that those projections will come true.

Both of those statements are sort of obvious. If you are trying to hype up your company to get people to buy it, and you get to write down "here's how much money we'll make in 2024," you might as well write down a high number because people like fast-growing companies. On the other hand, if that is your thought process then, you know, it is less likely that you'll actually make that much money in 2024. In theory those statements are in tension. In an efficient market, investors would know about Statement 2, which would make Statement 1 not true. If you know that high revenue projections are less likely to come true, you will not believe them; you won't pay more for a company based on its high projected revenue growth. But we are all fallible people and if a company is like "we will grow at 1,000% a year forever" you might be tempted. Anyway here is a paper called "Should SPAC Forecasts be Sacked?" by Michael Dambra, Omri Even-Tov and Kimberlyn George, finding that both of those statements are true: In this paper, we offer the first large-scale study on revenue forecasts disclosed in investor presentations given by SPAC targets. We document a positive association between the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in projected revenue and both market returns and abnormal retail trading during the five-day event window around the investor presentation. We also show that higher revenue growth projections are more likely to be optimistically biased and that firms with higher projections tend to underperform comparable firms during the two-year span following the SPAC merger. Overall, our results attest to the recent concerns expressed by both the SEC and the financial press, that SPAC firms' aggressive revenue projections compel retail investors, who end up faring worse on their investment.

If a company projects a high growth rate when it announces its SPAC merger, people buy the stock: We find that SPAC investors respond favorably to merger announcements as a function of the Revenue CAGR disclosed in the investor presentation. The mean investor presentation window cumulative abnormal return is 2.0% for firms in the lowest Revenue CAGR quartile and 11.0% for firms in the highest Revenue CAGR quartile.

And if it projects a high growth rate, it's likely to be wrong: We look at revenue realizations for the two years after a private firm has gone public. We compute forecast bias as the difference between actual and forecasted revenue scaled by actual revenue. In doing so, we find that revenue forecasts are biased overall and that the bias magnitude increases when revenue growth is projected to be higher.

My model of whistle-blowing is that anyone who finds themselves eligible for a whistle-blower award is either too ethical or not nearly ethical enough. One way to be a whistle-blower is that you and your buddies do a lot of fraud, and then you betray them to the government for a reward, which seems doubly unethical. The other way to be a whistle-blower is that you get a job in a new group and you spend five minutes there and say "everything here is fraud, I'm calling the police." Generally if you have that reaction it's because you're especially finely tuned to detect fraud? Anyway no prizes for guessing which one describes these guys: The Securities and Exchange Commission today announced that it has barred two individuals from the SEC's whistleblower award program, each of whom filed hundreds of frivolous award applications. The bars were issued pursuant to the 2020 amendments to the Whistleblower Program Rules, which were designed to allow the whistleblower program to operate more effectively and efficiently and to focus on good faith whistleblower submissions. Over the years, these individuals submitted award applications to the SEC that bore no relation to the underlying enforcement action for which they were applying. The filing of these applications consumed considerable staff time and resources, hindered the efficient operation of the program, and did not contribute to any successful enforcement action. The individuals were repeatedly warned to stop submitting the abusive filings, but refused to do so. "Frivolous award applications hamper our ability to efficiently process awards to meritorious whistleblowers who come forward with helpful information intended to assist law enforcement," said Emily Pasquinelli, Acting Chief of the SEC's Office of the Whistleblower. "Today's permanent bars send an important message that frivolous award filers will not be tolerated."

See, the SEC wants to attract people who were involved in fraud, but who are not currently doing fraud. It's a fine line! Would you like to chip in a few hundred euros to help a 27-year-old Harvard-educated Bohemian prince restore some of his family's castles? They own various palaces and "a collection of 20,000 artifacts, including works by Bruegel, Canaletto, and Velázquez, as well as hand-annotated manuscripts by Mozart and Beethoven," but some of them could use a refresh and he was hoping you'd help him out. Obviously he would keep the castles and paintings; after all he is a prince and you're not. But you would get the warm satisfaction of helping out a prince in his time of relative need. Is that not an appealing pitch? Well, okay, let's add a sweetener. He will give you a receipt. If you keep a receipts collection, you can put this one in your receipts collection. You can show it off to people. "This receipt represents the time I gave 100 euros to a Bohemian prince to restore one of his castles." Perhaps people will be impressed. Perhaps they will be so impressed that they want to buy the receipt from you. Perhaps they will pay you more than you paid. "Oh wow, I wish I had a receipt like that, tell you what I will pay you 200 euros for it." And then they can put it in their collection. "This receipt represents the time someone gave 100 euros to a Bohemian prince to restore one of his castles; I paid 200 euros for it," they will say proudly to some visitor, who will then offer them 300 euros for it. Perhaps a robust market will develop for these receipts. Who knows how much these receipts might be worth in 10 years? They are scarce assets; there will only ever be as many of them as this prince can get away with selling. That limited supply might make each receipt — particularly the early ones — worth way more than the amount you contribute. Early contributors — early investors in the prince-donation-receipts asset class — could become billionaires as their receipts appreciate in value. Honestly you can't afford not to chip in some money, to help this prince restore his castles, and get a receipt. The world is so strange, so strange: A 600-year-old Bohemian noble family is embracing the latest craze sweeping the crypto and art worlds, hoping that NFTs will help pay for the restoration of its artwork collection and an ancestral castle. The Czech Republic's Lobkowicz family — which once sponsored Beethoven, lost everything to the Nazis and Communists and then reclaimed their castles and artwork in the 1990s after the fall of communism — will auction a slew of non-fungible tokens and host a conference next month in Prague at the Lobkowicz Palace, from which you can see the entire city. ... This will kick off with a one-day, invitation-only conference called Non-Fungible Castle. It costs 400 euro to attend — payable in crypto, of course — and will explore themes around NFTs, such as whether the whole craze is a scam. Titles of scheduled panel discussions include "NFTs: Nothing F**king There?" and "What Are You Really Buying?" People will also be able to purchase blockchain-based proofs that they contributed to restoring certain items within the private collection. Several artists will sell NFTs with half of the proceeds going towards restoration.

What are you really buying. It is embarrassing for me that I wake up every morning and write a column instead of just selling people blockchain-based proofs that they gave me money. University Endowments Mint Billions in Golden Era of Venture Capital. Banks Are Really Cashing In on ESG Bonds. Bondholders Await Dollar Coupon Payment: Evergrande Update. China Evergrande to Sell Bank Stake to State-Owned Firm for $1.5 Billion. General Catalyst launches fund to buy future earnings of tech start-ups. Kraken Fined $1.25 Million for Offering Illegal Bitcoin Products. Bank Mergers Are On Track to Hit Their Highest Level Since the Financial Crisis. Ken Griffin tweets through it. Hong Kong Firms Start Flagging China Legal Risks in U.S. Filings. Is It Ever OK to Get Stoned With a Client? "The origin story of The Secret History." Dog earns Guinness World Record for longest ears. If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! [1] Later a court found that it's not even a monopolist in that market, but never mind that. Incidentally when I say "if Facebook dramatically raised the price …," I don't mean that too restrictively. If Facebook did something else that raised, as it were, the effective price of using Facebook, it would either lose customers (if it's not a monopolist) or not lose customers (if it is). Facebook is free but if it sold more of your data or whatever maybe you'd stop using it, I don't know. |

Post a Comment