| The great argument over equity valuations at present boils down to this: Everyone can agree that stocks, particularly in the U.S., look expensive, and everyone can agree that bonds look even more expensive. The question is how much the latter can justify the former. (And, more alarmingly, what happens if the latter ceases to be true.) If we take the raw dividend yield on stocks, then the S&P 500 appears to offer historically terrible value (as it does on many other metrics). It has tumbled dramatically over the last 12 months. This isn't just because of the rally in prices, but also because companies are happy not to raise payouts:  As on many other measures, the stock market looks extremely expensive on this basis, but still not quite as extreme as at the top of the internet mania in early 2000. Also as in many other metrics, this position is transformed if we also look at the yields available on bonds. If we take the spread of S&P 500 dividend yields over what 10-year Treasuries pay, we find they are almost equal. Historically, bond yields have tended to be far higher.  So on the crudest way to compare with bonds, stocks look a buy.

The International Dimension

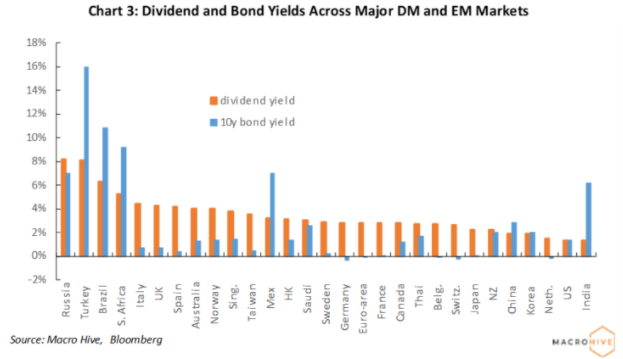

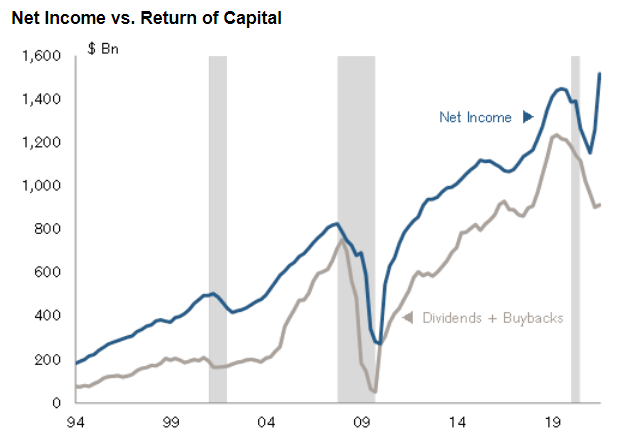

However, it still doesn't necessarily follow that U.S. stocks offer value. Bilal Hafeez of Macro Hive took to his Bloomberg terminal and produced the 10-year bond yield and the dividend yield for a range of large countries. For about 50 years up to the global financial crisis, it was taken as axiomatic that bond yields would be higher than dividends, to compensate for fixed-income's lack of growth. It isn't just in the U.S. that this is no longer the case:  Both China and the U.S. are in the camp where you get a lower yield on stocks than on bonds, reflecting pre-crisis orthodoxy. India, with the lowest dividend yield of the major economies, looks dreadful. Virtually the whole of western Europe, however, now offers far higher cash returns on stocks than you can get on bonds. The problems of the EU economy, and of the U.K., are well known, but the opportunities to pull in a healthy return of 4% or so from a well-supported dividend do look quite appealing in this environment. Investing in Europe involves swallowing hard and taking a risk in a deflationary environment. If you are more inclined to take the plunge into an inflationary environment, then a group of large emerging markets whose autocratic governments and questionable corporate governance have made them unpopular with investors are waiting for you. We know the risks of Russia, Turkey and Brazil. Their politics stinks. But the market does appear to be pricing those risks. Maybe it's worth putting in the work to decide whether the governments and companies in those countries really will be able to pay the yields currently on offer over the longer term. Yield Prospects As I mentioned, the fall in U.S. yields isn't just about the rise in share prices. Companies have been understandably reluctant to pay out cash in the pandemic era. That leads to a dramatic disjunction between their profits and the total amount of cash they devote to buying back stock and disbursing dividends. The following chart is from Jonathan Golub, chief U.S. equity strategist at Credit Suisse Group AG:  Over time, cash disbursed to shareholders tends to track net profits quite closely, which makes ample sense. But the sharp rebound in post-pandemic profits hasn't been matched by any rebound in the cash arriving in shareholders' wallets. Does this mean that we can expect a rebound some time soon? Golub argues that it does: When the global economy shut down in 2020, S&P 500 profits declined by -20%. Companies responded by cutting dividends and buybacks by an even larger -27%. More recently, earnings have jumped +32%, yet dividends and buybacks have increased by only +1%. We expect this corporate frugality to reverse over the next 1-2 years, supporting higher stock prices. While payout ratios are generally quoted as a percentage of earnings, they are more accurately paid out of Free Cash Flow. In recent quarters, FCF has expanded more quickly than profits, enabling further increases in dividends and buybacks.

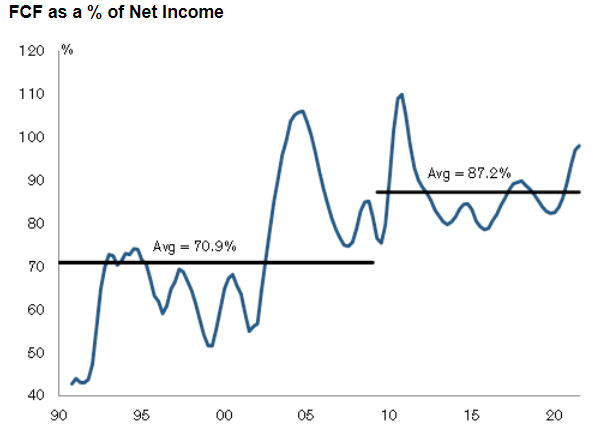

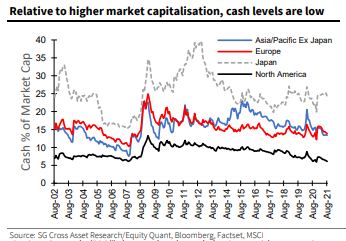

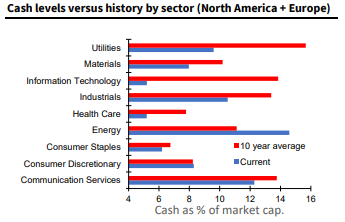

As he points out, companies do indeed have a lot of free cash flow, compared to their profits:  Unfortunately, there is another way to look at it. Andrew Lapthorne, chief quantitative strategist for Societe Generale SA in London, points out that higher share prices make buybacks more expensive (and beyond that, buying stock that is overvalued is a questionable way to spend shareholders' money). Cash may be high in relation to profits, but it is low in relation to market capitalization, except in Japan. In the U.S. buybacks are almost as expensive for companies on this measure as they were 20 years ago:  According to Lapthorne: Buybacks regularly come up in this conversation, but a return to booming buybacks comes with challenges, the main one being the size of the market cap itself. So, while cash balances are high in absolute terms, relative to market cap they are less impressive, particularly in the US, where the $2.2 trillion cash pile would only buy you back 6% of the non-financial market cap. So while capex and buybacks are once again growing, the US corporate cashflow surplus is heading back into negative territory, implying the balance sheet cash (or new debt) will be the source of funds. The reality of high equity prices is that buybacks are far less affordable than they were

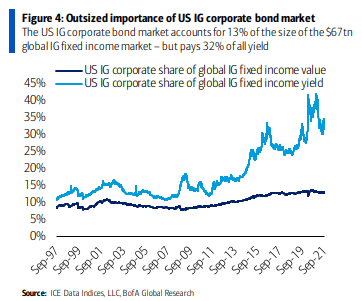

This exercise does, incidentally, explain why there is so much interest among Japanese investors in attempts to reform corporate governance. If it were easier for investors to force Japanese companies to disgorge more of their cash, there could be a very exciting opportunity to release value. In the U.S. and Europe, Lapthorne suggests that the only sector with enough cash to make it easier than usual to increase its disbursement to investors is energy:  For the time being it's noticeable that while European investors seem to be excited by the possibility of increased returns from companies, the same enthusiasm isn't present in the U.S. Companies with a record of buying back stock have strongly outperformed the average in Europe since the pandemic:  Nothing similar is afoot in the U.S. The Solactive buyback index for the U.S. was discontinued earlier this year. This is a similar chart of five-year performance comparing the S&P 500 buyback index (whose prior performance was very similar to the Solactive index) to the S&P 500 itself. Thanks in part to the continuing great performance of the FANG internet platform groups, high buyback companies have lagged during the post-pandemic rally:  How to Pay for It? There's one more awkward question about paying cash to shareholders: Where exactly does that money come from? If companies generate the cash by borrowing, it might not be healthy to expect them to continue paying. However, the laws of supply and demand are making it ever more attractive for large U.S. companies to raise debt. U.S investment-grade debt doesn't pay much in the way of yield, but it looks mighty generous compared to the yields on offer elsewhere. BofA Securities Inc. offers this devastating statistic: We estimate that the U.S. Investment Grade corporate bond market accounts for 13% of the size of the $67 trillion global Investment Grade fixed income market – but pays 32% of all yield.

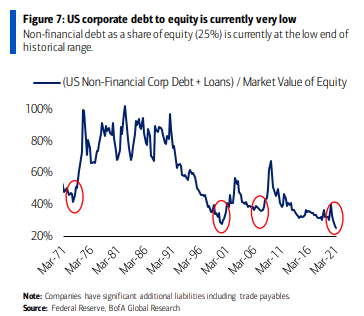

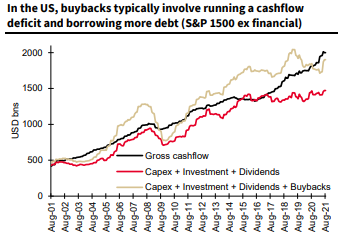

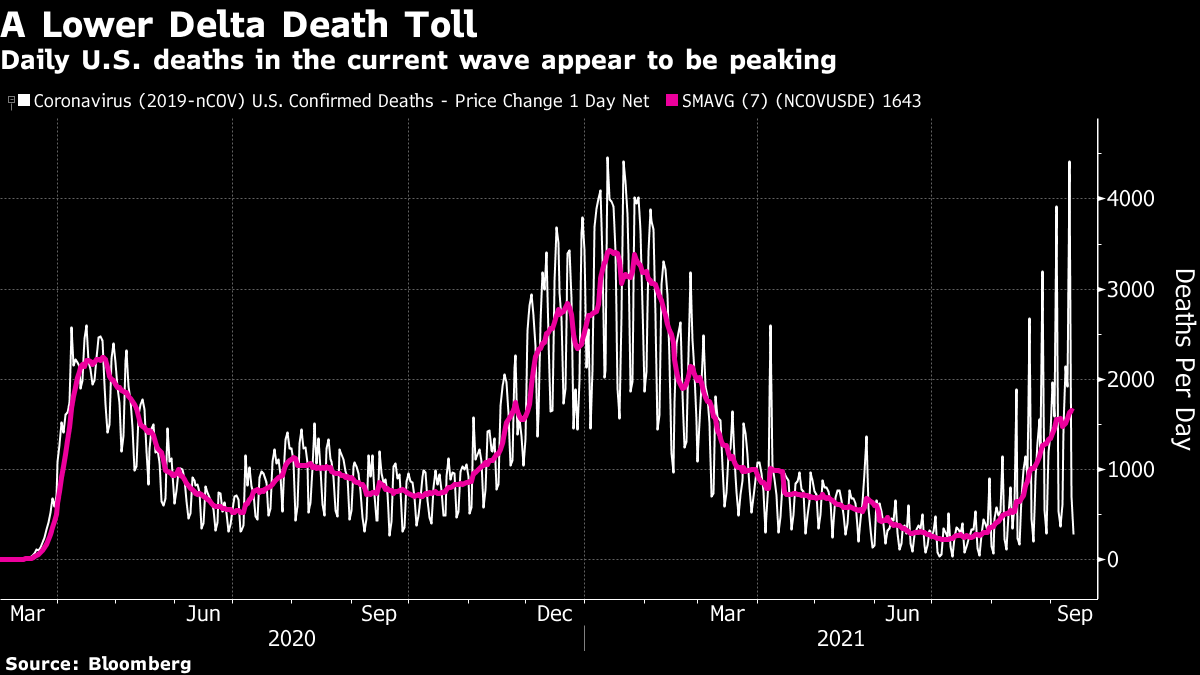

Here is that statistic in graphical form. The collapse in yields elsewhere has left U.S. corporates looking like a honey pot for the many large institutions that need to lock in a yield:  This gives U.S. companies a really big incentive to lever up. Thanks to the rise in the share price, the ratio of non-financial debt as a share of equity is reaching extremes. And note that all the previous extremes, when debt was particularly low as a share of equity valuation, came at a point when both the equity and credit markets were about to run into trouble:  U.S. companies can now, if they want to, borrow at cheap rates in order to buy back their own stock at very expensive valuations. Stock buybacks, as Lapthorne shows, tend to be funded by taking on extra debt:  Companies can do this, then, but it's not at all clear that their shareholders should want them to. The pandemic in the U.S. grows ever more political, with battle lines now drawn over vaccine mandates. It's very sad, and it has unquestionably had an impact on the economy. More importantly, it's hard to deny that more people have died than needed to over the last few months. But the good news is that the delta wave of Covid-19 does appear to have peaked. I'm getting very tired of producing Covid statistics from the terminal at this point, but here they are. Cases have clearly turned down nationally:  Meanwhile, as we all know by now, deaths tend to lag infections. But at least the rate at which deaths are increasing in the U.S. is slowing down, and still at barely a third of the appalling level they reached in winter:  With any luck, the economic figures for August, which will continue on Tuesday with the very important inflation data, will represent the worst of the delta wave. It doesn't seem too much to ask. I have a suggestion for light reading. While I was off, I managed to read through Robert Harris's Cicero trilogy: Imperium, Lustrum (sold as Conspirata in the U.S.) and Dictator. It's a series of novels that read like great political thrillers, because they are. But they also tell the story of how the Roman statesman Cicero rose from relatively humble beginnings to become consul in the days of the Roman Republic, largely through the power of his wits, and then of the steady and terrifying decline of that Republic. The final book of the trilogy takes us through the rise of Julius Caesar, his victory in the civil war, Caesar's assassination, and through to the rise of Octavian, who would eventually after another civil war do away with any lingering pretense that Rome still had a republic or a democracy, and install himself as the Emperor Augustus. Cicero's luck had finally run out by the time Octavian had made himself emperor, but the sweep of history the novels cover is remarkable, and the story they tell is very believable. It's easy to imagine that everything happened this way, and the lessons (many of them rather uncomfortable) for contemporary America are clear. It's great, unputdownable vacation reading, and you'll learn a lot from it. Especially if you have time off and the chance to bury yourself in a book for a few days, these novels are great. I really enjoyed them. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment