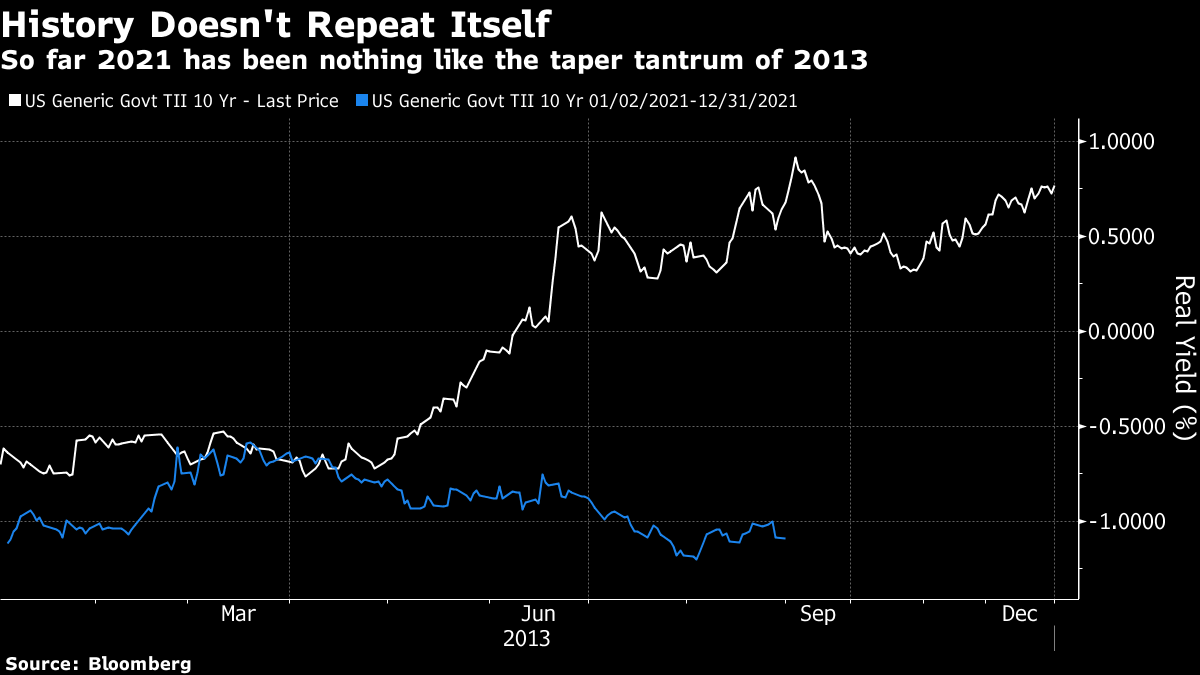

| So, what exactly went on at Jackson Hole? Emails to drop into my inbox over the last few days have referred both to a "dovish taper" and a "hawkish taper," and the Federal Reserve is being accused of both selling out on its aim to let inflation "run hot" and of going too far in that direction. So there's something for everyone. But what should we take as truth? Since I haven't touched a Bloomberg terminal in a week, working that out over a long bank holiday weekend in the U.K. involves, first, looking at what the market thinks about it, and the reality that the market has created, and second taking a look at what Fed Chairman Jerome Powell actually said in one of his most important set-piece speeches of the year. On the first, it's evident that the market interpreted the Powell message to mean there was far less need to worry about tighter monetary policy in the near future than they had thought. The last two trading days have seen the kind of reaction in stock and bond markets that might usually greet an outright cut in rates. Most importantly, this is how real 10-year yields have moved in August:  That's a dramatic response, suggesting the market perceives a determinedly dovish Fed. Real rates are marooned at levels far lower than ever seen before. They had picked up significantly, largely driven by the strong jobs report at the beginning of the month. But they remained lower than they had ever been before the pandemic, and now they are sinking back toward historic lows. That helped the main U.S. stock market indexes set further all-time highs. Armed with the knowledge that Powell had convinced the markets he was being nice to them, I then read his speech. It's not exactly Shakespearean prose, whatever its dramatic impact, but it carried a punch. By some margin the single most important line was this: The timing and pace of the coming reduction in asset purchases will not be intended to carry a direct signal regarding the timing of interest rate liftoff, for which we have articulated a different and substantially more stringent test.

Real rates had traced upward over the preceding weeks as investors reluctantly grasped that a taper of the Fed's $120 billion in monthly asset purchases was indeed going to happen this year. Powell's speech did nothing to disabuse them of this. He still allows for some variation in timing to take account of the next round of economic data and — critically — the progress of the delta variant. But barring something far worse than now seems likely, the Fed will begin to slow its purchases by the end of this year. What is interesting, and made far more explicit in this speech than before, is that Powell is presenting the decisions on tapering asset purchases and raising interest rates as entirely separate. Both are part of monetary policy, and both could be seen as tightening, but he managed to couple confirmation that a taper is imminent with reassurance that rake hikes aren't. Tapering merely required "substantial further progress" compared to the dire situation at the end of last year, and we're pretty much there. Raising interest rates will require "maximum" employment, and under the new regime heralded a year ago in Wyoming, even price gains above target won't change that; average inflation targeting, or AIT, means that the index can be allowed to run above the official goal of 2% for a while before borrowing costs start to go up. That is what cheered the markets so much. There is a different, and important, debate to be had over whether they should be happy, and whether the Fed will regret being so lenient about inflation in the long run. But for the short term, the investment community is delighted that the doves are still in control, and that accommodative economic policy will be around for a while longer. Lessons of History Why has Powell chosen this approach? History has many warnings but it's fascinating to see which he chose to accentuate, and which to downplay. What he didn't choose to mention, probably because it was unnecessary, was the episode that has preoccupied Fed-watchers since asset purchases were ramped up early last year; the taper tantrum of 2013. On that occasion, his predecessor Ben Bernanke started talking about tapering asset purchases in May, and provoked a dramatic rise in real rates that sparked a near-crisis in emerging markets. As bond yields rose sharply in the first two months of this year, it looked as though there was a real danger of a repeat. Whatever else the Fed can be accused of, it has avoided making that mistake. Communication throughout the year, moving from "not even talking about talking about" tapering, through talking about it, to now making it a matter of dependence on the data, has done a great job of preparing the market. Far from a tantrum, real yields remain at historic lows even as investors assume that a taper is coming this year. Without saying as much, the Fed's guiding historical narrative this year has been 2013, and the need to avoid any meltdown of the bond market. And 2013 per se won't be repeated:  Having avoided miscommunication and a preemptive tantrum, the issue will now be whether the practicalities of tapering can happen without causing a bond market accident. The Fed's purchases are now such a huge proportion of all available bonds that it will be difficult to withdraw without provoking a lot of volatility. Perhaps to try to reduce the risk of such a thing, Powell chose instead to emphasize a story from many decades ago, that detailed the risks of being too hawkish: The early days of stabilization policy in the 1950s taught monetary policymakers not to attempt to offset what are likely to be temporary fluctuations in inflation. Indeed, responding may do more harm than good, particularly in an era where policy rates are much closer to the effective lower bound even in good times.

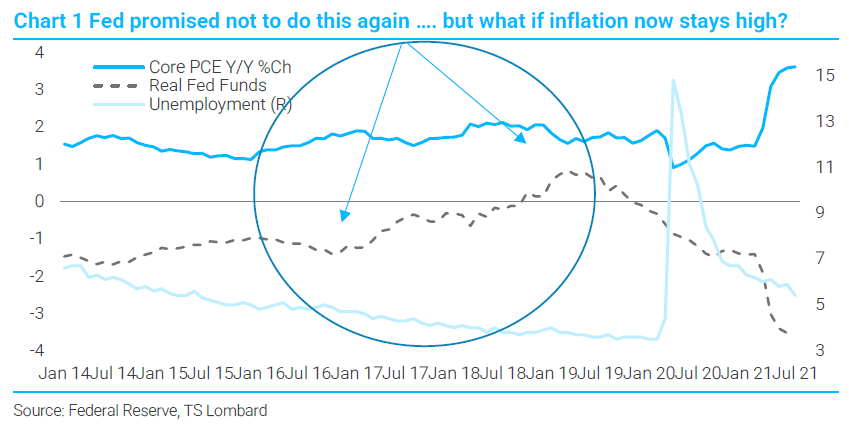

That's a strong hint that he really is prepared to err on the side of allowing inflation to go too high. It was safer to cite that episode than a much more recent one — the Fed's decision to raise rates starting in late 2015, even though inflation remained utterly quiescent. As rates started at effectively zero, there were plenty of defenses for this. But it's now widely regarded as a mistake. Effectively, as Steve Blitz of TS Lombard put it, this was Powell's way of promising he wasn't going to make that mistake again:  For now, this argument has evidently worked. There are differences between asset purchases and the setting of overnight interest rates, and Powell has for now persuaded the market to treat them as conceptually different. But that still leaves the biggest argument. Is there really any inflation ahead, and will the Fed really hold its nerve and stay its hand if price pressures persist? Inflation Indicators The issue of whether there is inflation in our future, and if so whether the Fed is prepared to go through with the dictates of the last Jackson Hole meeting and adopt average inflation targeting, is likely to be the dominant financial issue for the next year. Here, the Jackson Hole speech is open to plenty of different interpretations. Powell went through five reasons why the current dose should indeed prove transitory. This prompted Blitz to argue that he was protesting too much, and was evidently worried about inflation. That will be a real test of resolve because raising rates would damage growth: AIT will be tougher to sustain as policy than originally scripted. Powell let us know this by revealing the inflation doubt creeping into the Fed's conversation. The problem with breaking the AIT promise is that it also takes down the probability of an economic advance built on investment by, in part, rekindling a dollar bid underpinned by Fed policy that, in turn, damages the tradable goods sector of the economy, thereby potentially putting a lid on domestic capital investment by business.

Meanwhile, there is the continuing real risk of the opposite problem; deflation has preoccupied the West for a decade. If secular stagnation persists, then it's not at all clear what a central bank can do about it (just ask the Bank of Japan), but raising rates could be an issue. The continuing concern about secular stagnation helps explain why many economists, far from appreciating the "dovish taper," were alarmed by how seriously the Fed was taking the possibility of inflation. The most trenchant example of this that I've seen came from Steven Ricchiuto, U.S. chief economist of Mizuho Securities USA LLC, who suggests that the markets are correctly signaling a deflationary risk: Since the 1990s, however, the global economy has been shifting toward excess supply of tradable goods in the wake of technological advances, globalization, and the aging of the population. Economists have been slow to recognize this transition, partly because it renders the bulk of modern economic theory obsolete. As such, policy makers are blind to the deflation risks they face, even as 24% of the global bond markets trade in negative rates and Europe looks to have slipped into a deflationary spiral. We had hoped that the Fed's policy shift announced last year was policy makers realizing that excess supply is a problem and that the Fed would allow the economy to run hot to ward off deflation. Recent Fed policy decisions make it clear the FOMC can't let go of its inflation fighting framework, even when it is outdated.

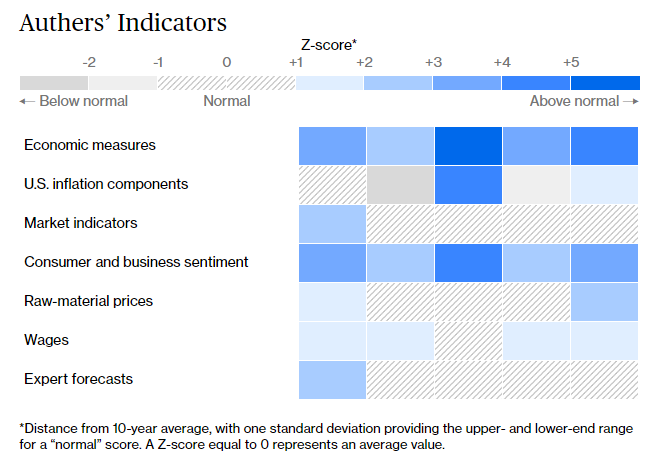

Many out there believe that the inflation issue is over-egged in the media, which is understandable. But the stakes are high, and the divisions over whether the events of the last year will lead to a secular increase in inflation are deep and hard to reconcile. For our own modest attempt to track the emerging evidence on inflation, the regular inflation heat map has been updated and can be found here. The summary heat map is barely changed from the last update, but there is plenty of data to come in the next few days:  The main point to note is that expert forecasts and market indicators suggest the risk of inflation is minimal to non-existent, even as the measures themselves are elevated. Perhaps the key line, on which the debate will now turn, is the labor market, where wage growth is running a bit above the average for the last decade. Numerous forces have kept wage growth down for decades, bringing deep discontent but also low inflation. The key question for Powell and his colleagues is whether labor now has enough power to force a wage-price spiral. He has successfully prepared the ground for a dovish taper; the labor market will determine whether he can perform the same trick for interest rates. Flying for the first time in a year and a half allowed me to catch up with movies that were all the rage 18 months ago. On the way to Heathrow I watched Parasite, a South Korean fable about class and social inequality that's utterly brilliant. It manages to be genuinely funny and make biting commentary on the Korean reality that also applies to most other societies around the world, while also being a remarkable fantasia that stretches your ability to believe. And a warning that it gets violent at the end. Unlike one or two other Oscar winners of recent vintage (Argo or Green Book being pet peeves), this one imprints itself in the mind and is destined to be a classic. If you didn't see the movie in theaters, in that brief window before Covid-19 descended, it's really worth catching. And enjoy what for many of us will be the last week of summer. I will be back next week with some ordered thoughts from the homeland. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment