18 books that deserve more hype ✨

| The books that have people asking,

More for your #TBR list Fun & funny

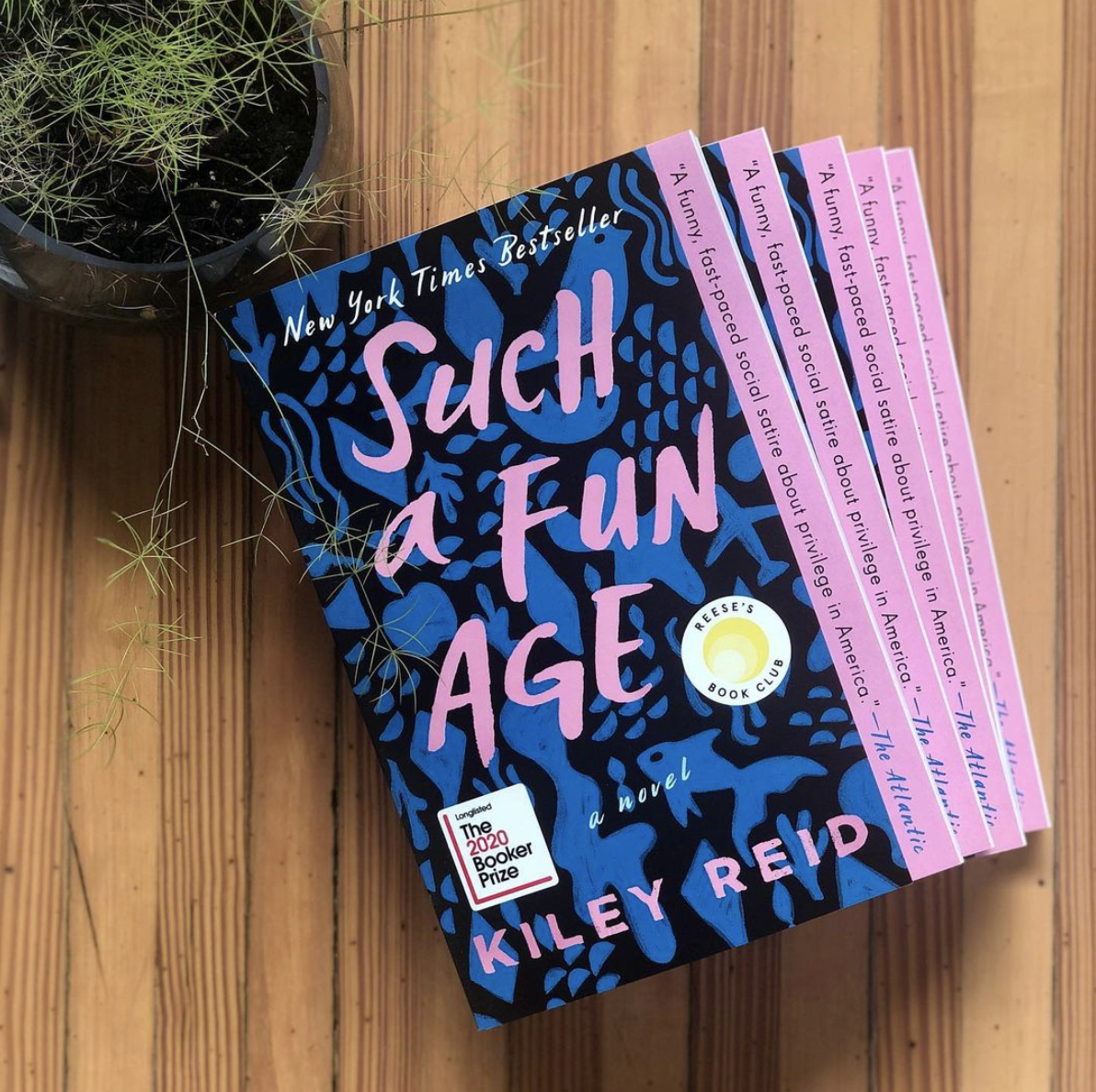

Read this if: You want to recommend next month's book club pick. Credit: @kileyreid Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid

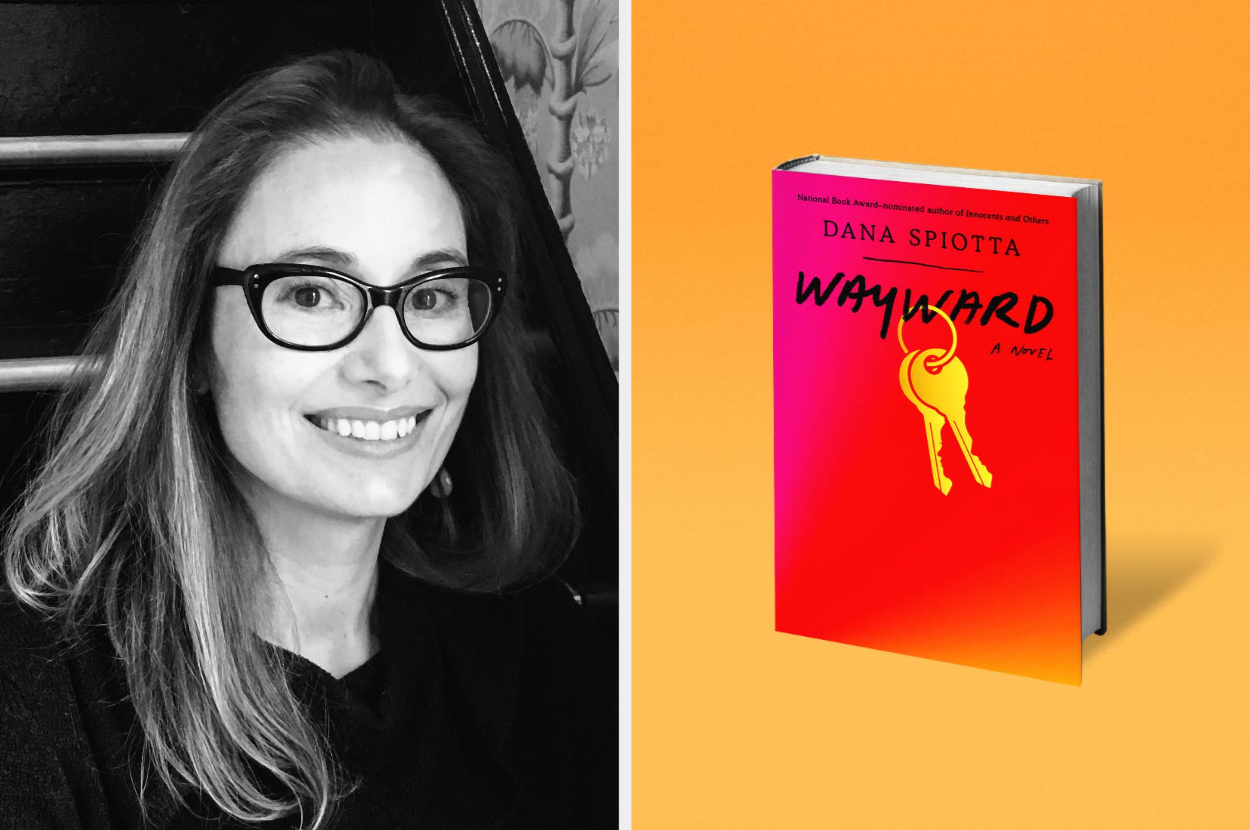

The beauty of Such A Fun Age is not only in the complex characters, but Kiley Reid's ability to showcase the insidious nature of racism, privilege, and prejudice in a world that feels authentic to the twenty-something experience. The book begins with a racist incident as a shopper falsely accuses 25 year old Emira Tucker of kidnapping the white child she is babysitting for the evening. We've seen this play out before time and time again; however, Reid dives further into what happens when people of privilege try to right their wrongs. The result? White saviorhood. We watch characters fumble through their attempts to make good without true care for Emira. It's a quick read that doesn't necessarily provide us with all the answers to white saviorhood but opens dialogue for whether intentions are as important as impact. Spoiler alert: they never are. Pick up your copy now and get lost in this story because the plot twists are well worth the wait. Get your copy here. —Kori Clay Credit: Jessica Marx; Knopf WAYWARD is narrated in alternating sections from the point of view of Sam, a middle-aged woman, and Ally, her (almost) seventeen-year-old daughter with a secret. The novel was first inspired by my own experiences of aging. I had the sense of time moving faster, and I had the sense that I was ill-prepared for what was to come: losing my parents and sending my child off into the world. As this was happening, a kind of peri-menopausal insomnia kicked in. Things (my body, my emotions) felt out of control. Sam is imaginary and very different from me, but we have this much in common. Aging is the reminder/realization that your body is not actually within your control; that you, in fact, inhabit a body. These terms apply to all of us but are experienced more starkly in menopause. And I wanted to write about menopause because I get the impression that we aren't supposed to talk about aging, that it is a private embarrassment to be endured.

In Wayward, Sam walks away from the comfort her middle-class suburban life has afforded her and becomes a sort of woman on the margins. What's exciting about writing about women who walk out of their manicured lives and take up nontraditional ways of living?

Sam's mother is dying, her daughter is growing up, and her husband ignores her. Sam deliberately, perversely, discomforts herself. She gives many reasons why she feels she has to radically change. She wants to see herself clearly, but that is hard. Sam is a "good liberal," a feminist, but she is also clueless about the world around her. "Ignorant but not innocent," is how she puts it. Following Sam as she recklessly (but earnestly) changes her life is a way to play out certain impulses people have. Ruptures are interesting to me; they create dramatic tension. People in crisis reveal themselves. Sometimes they even change. But when someone walks away from their life, there are consequences. In Sam's case, her teen daughter stops talking to her. Mothering her daughter has been the organizing focus of her life — and because Sam left, she misses the signs that her daughter is having a torrid sexual relationship with a much older man. We see the daughter's own perspective about her secret life. The reader sees the gaps and connections between these two characters and gains a perspective that neither Sam nor Ally has. That is a big part of why fiction can be so compelling — we see more than the characters can, we get the whole view. The book is really about their relationship, and with Sam's ailing mother too. It becomes a portrait of a family in transformation.

Sam blows up her life after buying a house. This isn't the usual mid-life crisis starting point. In fact, there's no massive betrayal that leads Sam to blow up her life. Can you talk a little bit about writing about a woman's mid-life crisis — and how it looks and feels different than a man's?

Sam is an eccentric; she has a special feeling for old, forgotten buildings and falls in love with a wreck of a house. Having said that, I think old houses do speak to a lot of middle-aged women. To Sam, it is a beautiful ruin, which is a little like how she views her own body. One of Sam's graces is that she makes a lot of jokes, especially about her own hypocrisies, contradictions, and vanities. I didn't want the cliché of a mid-life person (woman or man) having an affair as a way of coping with aging. Sam is after something more fundamental: a sense of purpose, maybe.

Sam also grapples with aging as she navigates starting over. So many of our cultural conversations are about women "turning back the clock" on aging while the aging process is hidden away or something to combat. I can't remember a novel that writes so candidly of the experience of perimenopause and the physicality of it. Why did you want to put women's aging front and center in the novel?

Not all people have menopausal symptoms — but if you do, they can upend your life. I observed that people were not talking about it enough. I got the sense that we are supposed to be ashamed of aging. It is unattractive or whatever. I wanted to write about what it feels like to inhabit a menopausal body. I think it is a compelling experience — it forces you to accept that time is going by and running out. Moreover, the insomnia — which Sam experiences — gives you plenty of time to contemplate your mental and physical state. And perhaps the hormone flux unleashes more emotion than usual, maybe the hormones are a kind of truth serum, or maybe they distort things. These are some of the things Sam is trying to figure out.

Sam finds a group of people who loudly embrace their aging. The book has a bit of fun with satirizing various forms of resistance. These women resist youth culture hegemony, as they put it, by being defiant "Hags, Harpies, and Harridans." I didn't want Sam to be preoccupied with her wrinkles or her dwindling attractiveness. She doesn't care about that — it seems trivial to her. But the seemingly confident women she befriends are also not all what they seem in the end. Where she lands is not about being in-your-face or being invisible. She ends up with a broader perspective; she tries to get over herself. She is not the center of everything, and she makes peace with that, I think.

The 2016 election was a moment that shook a lot of white women out of their complacency and after the shock of it, made them see the world with a new kind of urgency. (This despite the fact that many white women actually voted for Trump.) We saw people who had never engaged in protest suddenly hit the streets. What spurred you to use the election as a backdrop for Sam's life change? And was the election your catalyst to write the Wayward or did you start writing it before that?

For Sam, the Trump election is a clarifying event. She already knew the ugly truth it revealed about the state of America, but she didn't expect such a frightening manifestation. That is a function of her privilege, her complacency, and, she realizes, her own collusion with the status quo. She was "ignorant but not innocent." She understood there was great inequity in the country, both structural and personal. She knew about the racism, the xenophobia, the misogyny. But the election makes her realize that the state of things is on her, too. As an aging woman, she is trying to reckon with feeling both complicit and disdained. It was shocking just how much mileage Trump got out of disgust for women, and how many white women still voted for him.

Anger is also a galvanizing force in the novel. Can you talk about what makes women's anger in particular so compelling to write about?

We do live in angry times. Women, young and old, are judged more harshly for expressing anger than men are. It is unbecoming, still. But anger is complicated, and that interests me. There is piggish, entitled, Trumpy grievance and then there is what Rebecca Traister writes about, righteous rage that compels you to action, to change, to testify. Sam's anger is also a form of self-interrogation. Sam is mostly angry with herself. Sam's anger goes from a form of self-pity to something less self-focused. She stops being a spectator to the world and becomes, maybe, an honest witness. Ally, her daughter, is angry, and she also evolves in terms of where her anger is directed.

What are you working on next?

An environmental opera about the Newtown Creek in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. I have two brilliant collaborators: a composer, Kurt Rohde, and an artist, Marie Lorenz.

More From BuzzFeed |

Post a Comment