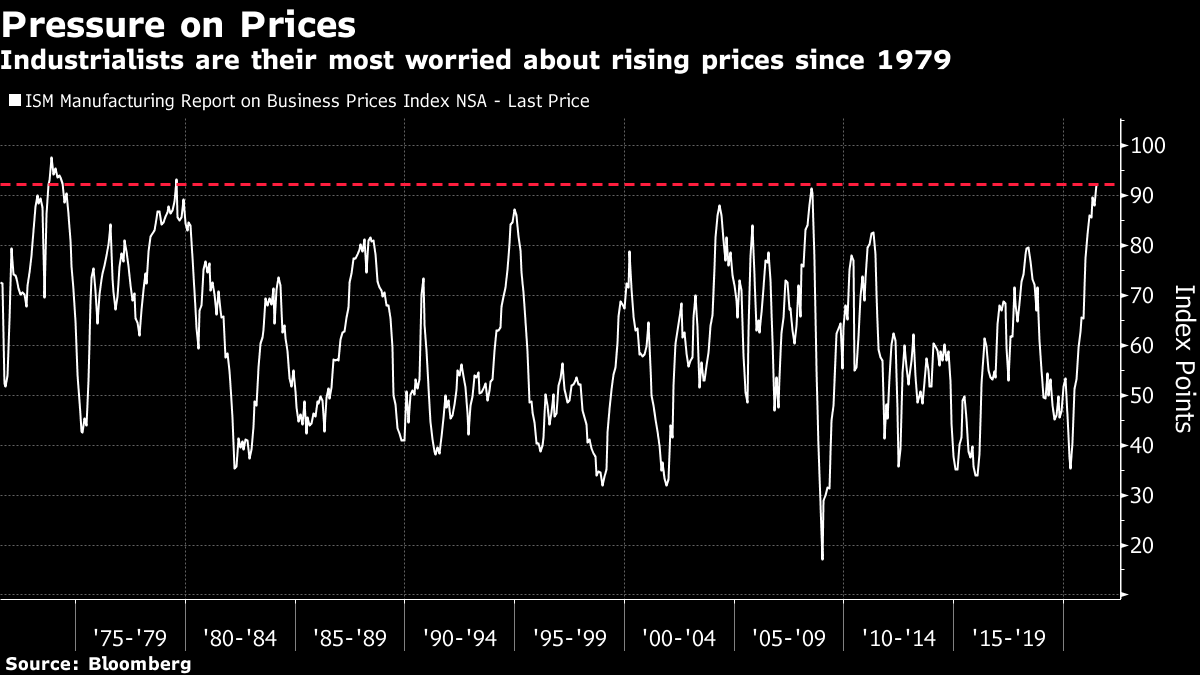

Wait for ItBusinesses are still bedeviled by post-pandemic logjams. There are signs of improvement, and they are enjoying growth, but the upward pressure on prices is still intense, and growing. That was the main readthrough from Thursday's regular download of monthly data. The U.S. ISM manufacturing survey dropped very slightly, but remained at high levels, confirming that the peak growth rate is behind us, while also showing that expansion continues at a robust pace. But the reading on prices paid to suppliers rose to touch its highest level since 1979. It has been higher than it is now on only eight months out of the last 50 years:  Crunching further into the details, the index for backlogs dropped slightly, having earlier this year hit its highest level since the ISM started asking the question almost 30 years ago. Backlogs, arguably another form of inflation, remain very high, but it is encouraging that the peak appears to be in:  The ISM also includes a question on whether deliveries are growing faster or slower. The excess of those finding them slower compared to those seeing them speed up dropped slightly, after hitting its highest in May since records began. But again, this number remains elevated. If inflation is to prove truly "transitory" in any meaningful sense, deliveries will need to start accelerating up soon:  What effect has all of this had on inflation expectations in the market? Not a great deal. Bond market breakevens dropped in June, particularly after the Federal Open Market Committee shifted its communications in a more hawkish direction. They have risen over the last two weeks, and climbed a little more after the ISM data came out, but remain at the kind of levels that suggest this burst of inflation will be shortlived, averaging about 2.5% for the next five years, and 2.2% for the five years after that, an outcome with which the Fed would probably be happy:  Now let's all get ready for non-farm payrolls, before America can retire to spend a weekend overeating in the sun. While you wait for the last big data download of the week, it might be interesting to listen to this podcast from MacroHive, which features an interview with London School of Economics academic and former Bank of England official Charles Goodhart. As distinguished a figure in monetary policy as it gets (he even has a law named after him), Goodhart, with his co-author Manoj Pradhan, has been banging the drum in recent months to make the case that demographic factors could drive a secular rise in inflation. A dose of long-term context might do us all good. The Bernstein Bubble CallThe impassioned debate over whether we really have an investment bubble saw a surprising new entrant this week when Rich Bernstein, who heads the eponymous Richard Bernstein Advisors LLC, published a piece listing his five customary tests, and found that the current market passes all five. I take Bernstein's views on this seriously because he was a prominent and consistent bear in the years leading up to the implosion of 2007-08 when he was a senior strategist at Merrill Lynch (then still an independent investment bank). Subsequently, he was persistently and consistently bullish about asset prices in the long and dissatisfying recovery that followed. He cannot be dismissed as a perma-bear, and the last time he made a bubble call he was right. There are two legs to his argument. The first, which I will deal with swiftly as this is well-covered ground, is to look through the reasons why this qualifies as a bubble. The second, much more complicated issue is what we should do about it. So, here are Bernstein's five tests. Does the market have: - Increased liquidity? Yes, I think we all know that. Enough said.

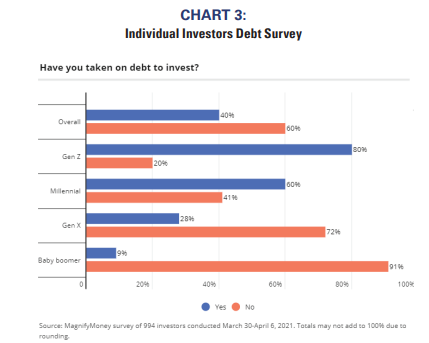

- Increased use of leverage? Yes, even if the credit market hasn't descended into some of the absurdities that were witnessed in 2007. Bernstein points to this survey of individual investors that showed increasing numbers in all generations borrowing to buy stocks:

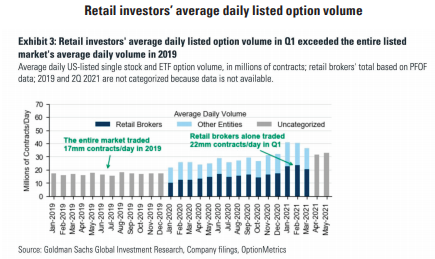

Bernstein also cautions that borrowing isn't the only way to increase leverage. "Investors have gravitated to the embedded leverage within single stock options." The following chart, of Goldman Sachs Group Inc. research which Bernstein used in his note, "shows how retail brokers place more single stock options trades than the entire size of the options market two years ago."  - Democratization of the market? Yes, again, we all know that this is going on. "Democracy" is the kind of motherhood-and-apple-pie issue to which it is hard to object. But if it means giving a large number of people with no prior experience of investing the opportunity to move markets, it can be dangerous. And the similarities with the late 1990s, when Charles Schwab, Datek and other discount brokers were pioneering the first great wave of individual day-trading, are closer than you might think. These magazine covers (from 1997 and 1999), sent to me by AJO Partners of Philadelphia make that point pretty clearly:

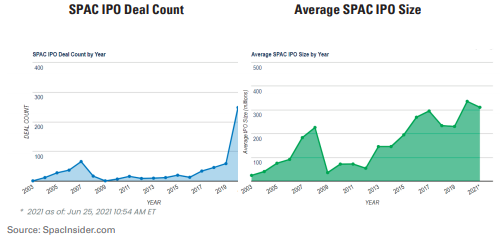

- Increased new issues? SPAC boom anyone? As the most speculative of speculative IPOs have increased greatly, this is another yes. Bernstein offered this chance of the rise in IPOs through special acquisition vehicles:

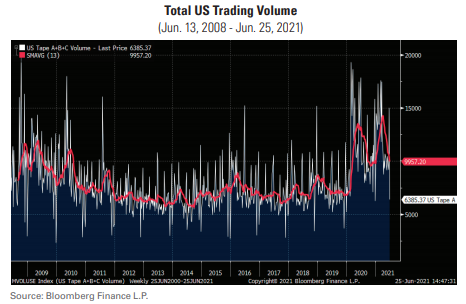

- Increased turnover? Again, yes, we all know this is going on. Total U.S trading volume is running 25% above its norm:

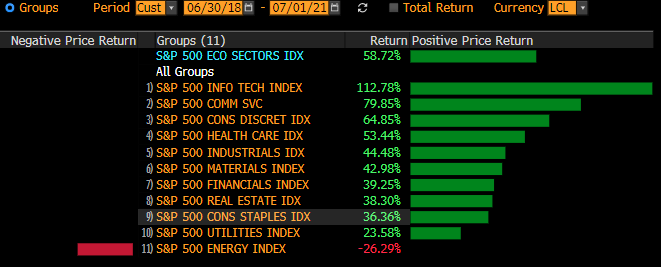

So, if we accept Bernstein's five criteria, and they're all reasonable, we are obliged to conclude that this is, indeed, a bubble. Now, what do we do about it? This is where it gets more interesting. Timing a bubble is prohibitively difficult, and can prove very expensive. Many of the various value investors who sat out the dot-com boom wished they hadn't; in the fullness of time, the investors who stayed with them did better than those who had piled into tech stocks, but that wasn't much use for the fund managers who had seen many clients yank their money. Some famous managers lost their jobs before the bubble burst. Things are even worse now that bonds and cash offer such unattractive alternatives to stocks. But Bernstein asks if this bubble has lifted the entire market equally, and finds that it hasn't. That creates an opportunity for survival. He says: Over the last three years, only three of the eleven S&P 500 economic sectors have outperformed the market, and those three sectors (Technology, Communication Services, and Consumer Discretionary) are at the center of the bubble. The remainder of the market has lagged, and the energy sector is actually down more than 15%. The Russell 2000 small cap index's performance would rank about 8th or 9th in the table, so the broader market has indeed been left behind.

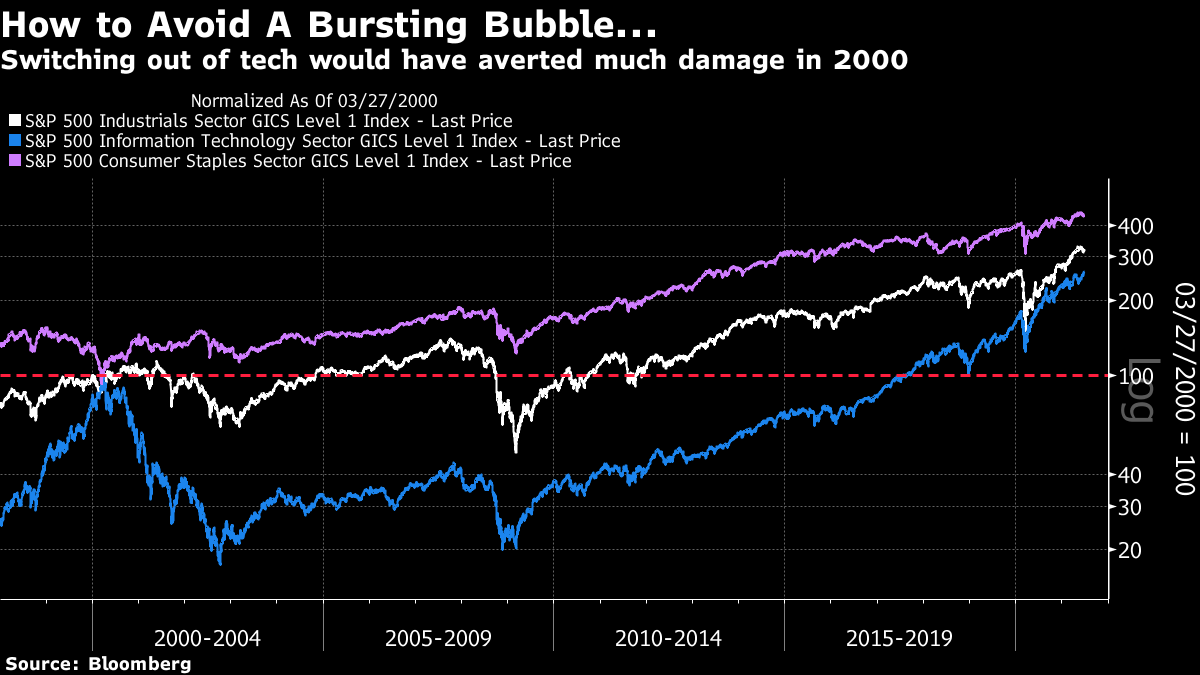

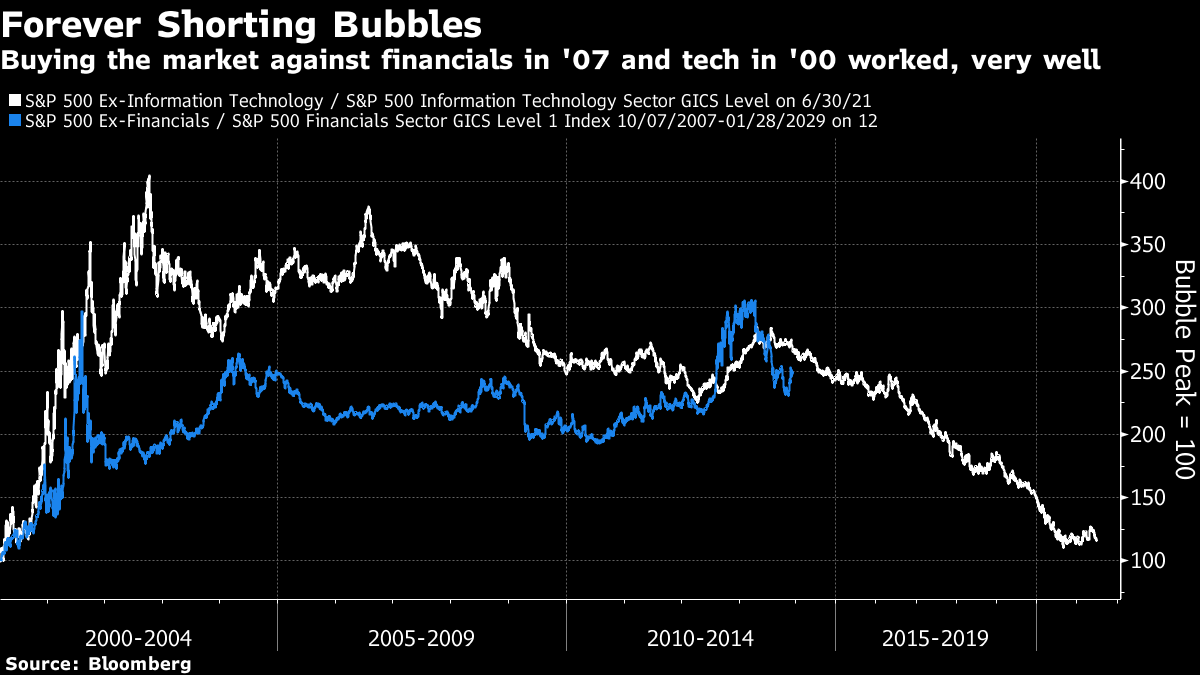

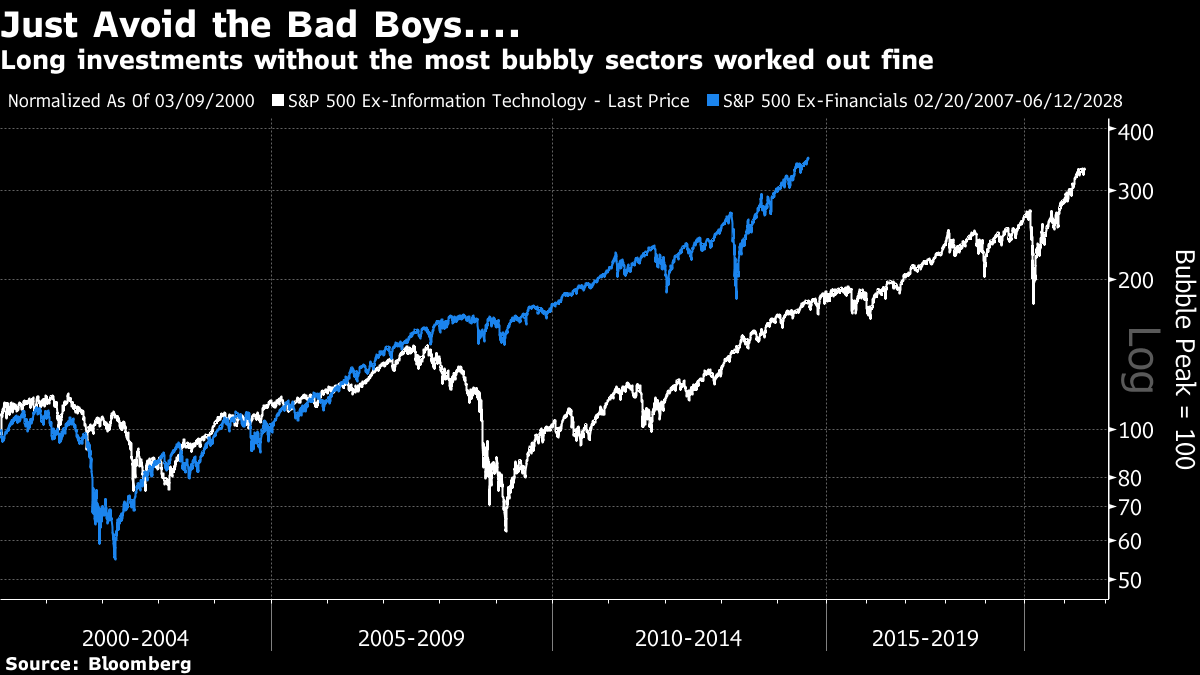

Here is that chart, as it now appears on the Bloomberg terminal:  That leads to a straightforward approach: avoid the momentum plays (which have been relatively pegged back for a while but still have a long way to go), and invest in the sectors that haven't shared in the bubble to the full. Bernstein suggests investing in recently boring U.S. sectors, and also in non-U.S. markets which — as I pointed out yesterday — continue to lag ever further behind the Americans. If the post-pandemic recovery unfolds as we all hope that it will, these are the kind of stocks that we would expect to do well in any case. Would this approach really have worked historically? Obviously timing matters, but it would have done much better than I had thought. This is how the S&P 500 tech sector performed compared to industrials and consumer staples, starting on the day the market topped in March 2000:  Consumer staples happened to sell off the month before, and you could have made money in the sector almost uninterruptedly. Industrials would have held their own. Buying into the tech sector at the top would have been an unmitigated disaster. Even now, after a protracted tech rally, tech hasn't caught up with industrials or staples. The bubble that peaked in 2007 was a little different, in that it was a true "everything bubble." Overall U.S. equity market multiples weren't so grotesque, but there were over-extended bull markets in credit, commodities, and emerging markets. There was no obvious shelter and indeed the hedge funds that managed to do brilliantly in the aftermath of the 2000 bubble failed to repeat the trick. But a policy of avoiding the most bubble-icious sectors would again have limited the damage nicely.  How about being more aggressive? An attempt to profit from a bubble would involve actively shorting the bubbly sectors and buying the rest of the market. If the timing was correct, this also proved remarkably successful. There were great differences between the markets that peaked in 2000 and 2007, but the results achieved by shorting the "epicenter" stocks and buying the rest were very similar:  The problem with this chart, of course, is that it starts at the absolute perfect time for a contrarian bet. Here is what would have happened if you'd taken a short position in the Nasdaq 100 balanced by a long position in the S&P 500, in 1997, three years before the market topped. Alan Greenspan had already inveighed against "irrational exuberance" a few months earlier, and this investment includes a long position in something as broad and stable as the S&P 500. Nevertheless, you would have lost almost 70% of your money at the worst, and it would take more than five years to break even. It's probably best not to try this one at home:  Without doing anything dangerous like shorting, how would the results have been in absolute returns to just buy everything but financials in 2007 and tech in 2000? Again, the results are surprisingly similar and surprisingly good. Your portfolio would have gone under water for a year or two, but would be showing a profit after four years, and rally merrily thereafter:  The debate over whether we are really in a bubble will rage on. And betting on an all-out burst involves fighting the Fed, which the market cliche-meisters tell us we must never do. But a shift into the sectors that have done the last few years, like staples, industrials and even energy, looks like an idea with a lot of upside and not too much downside if there is no bubble to burst. Which is to say that it seems a pretty good idea. Survival TipsSometimes only YouTube will do. Let me offer a couple of discoveries that might lighten your mood. First, try Jess Greenberg, who is an extraordinarily good singer and guitarist, and who has been posting videos of Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin acoustic covers for years. She's seriously talented — and I discovered on researching this today that she's also British and currently engaged in a very successful City of London career, currently at BlackRock Inc. after a few years at Winton Capital Management. I doubt I've ever met a fund manager capable of playing the guitar as well as she does, and there's something very life-affirming about the videos. That said, you might want to avoid the sexism in the comments threads, although that's not her fault. Alternatively, from my son there is a recommendation to keep an eye on Jelle's Marble Runs — televised marbles. It helped make up for the lack of sport in the worst of the lockdown, but it's still fun even now. And I can also recommend (via my younger daughter) Seth Everman, who shows how to recreate popular hits using household objects. There is some fun to be had in front of a computer. Have a good weekend everyone, even if it isn't a long one. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment