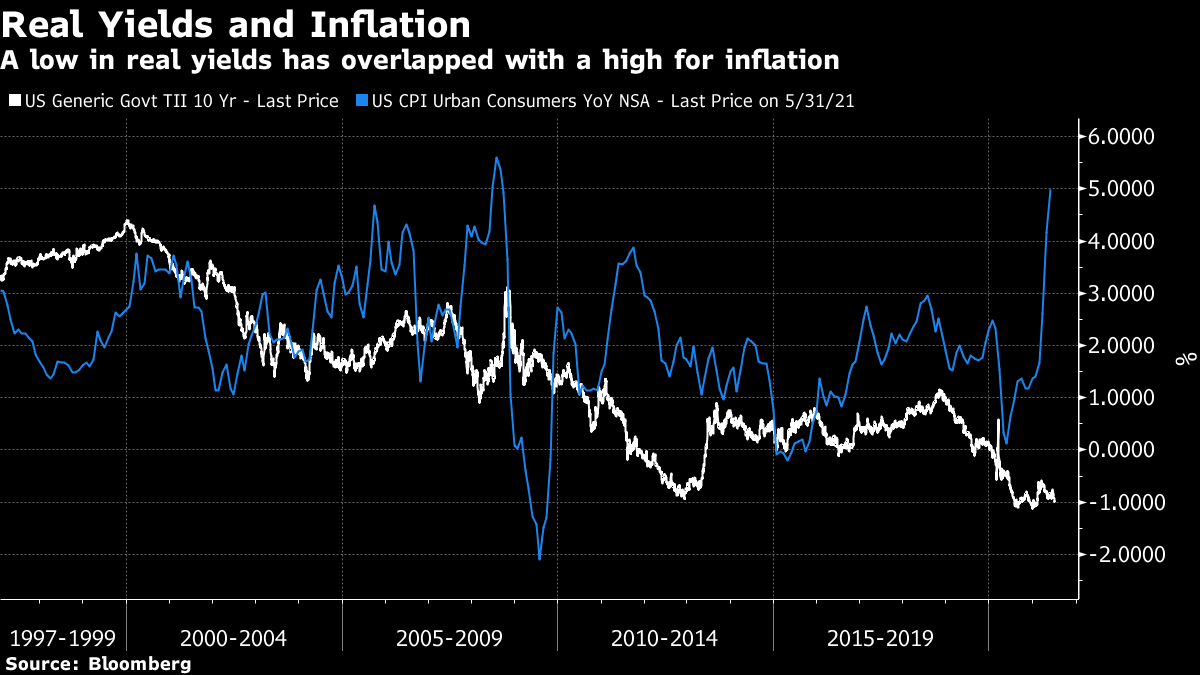

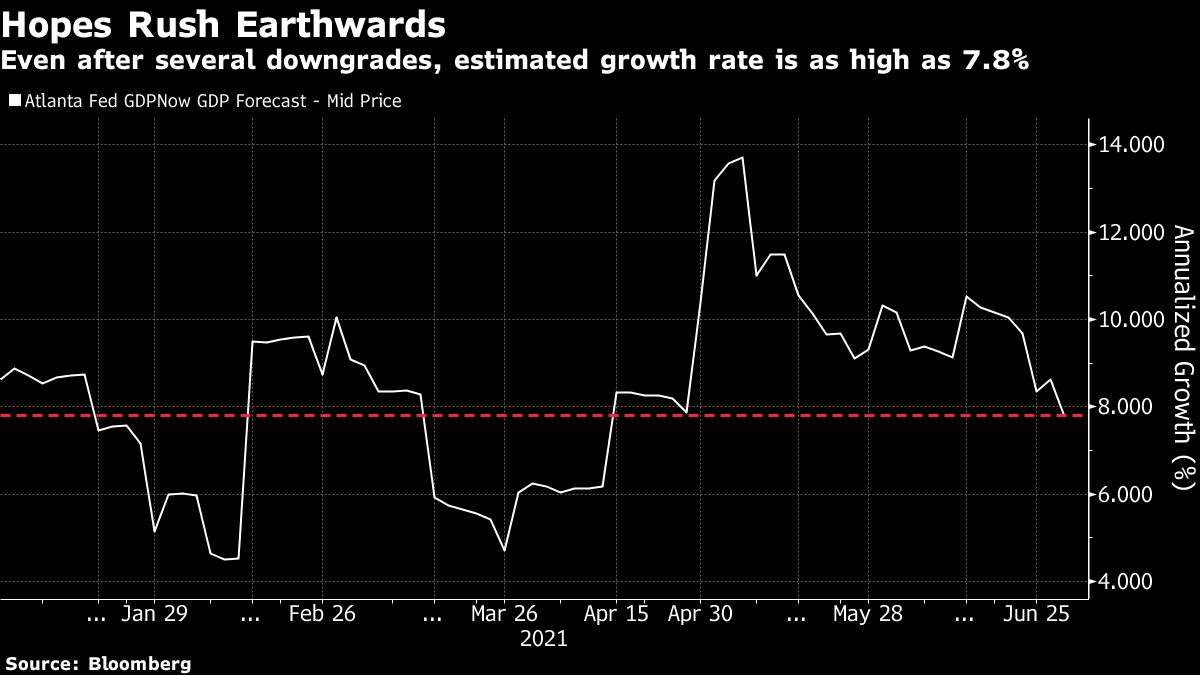

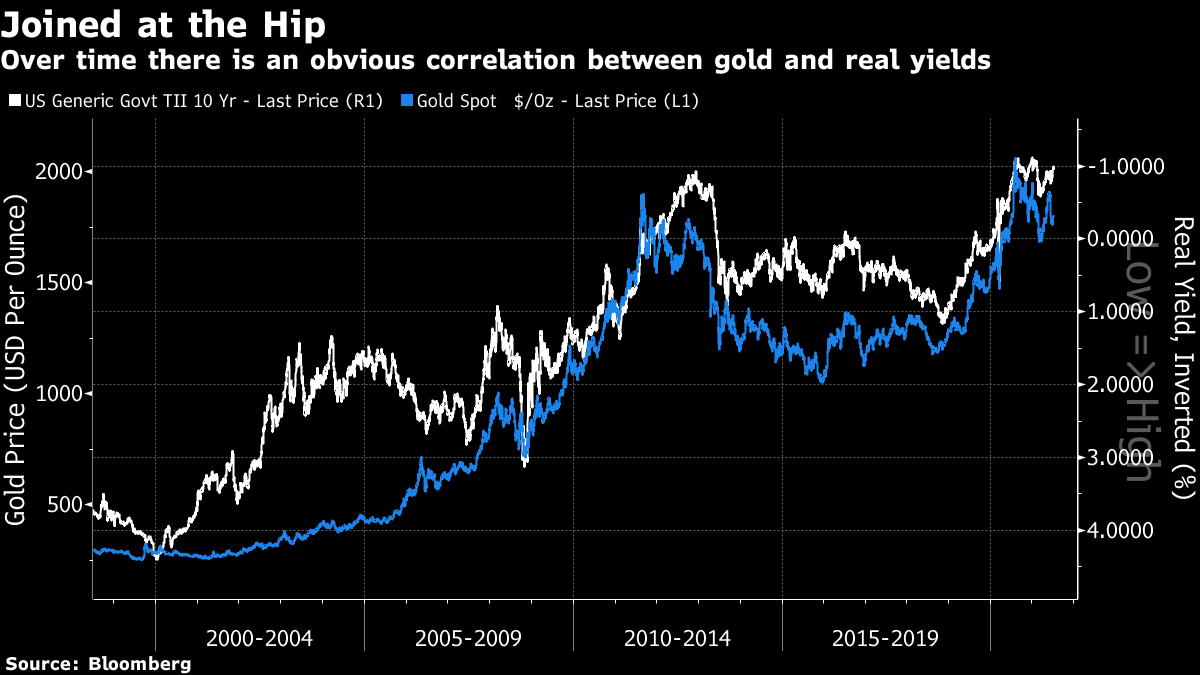

Over to You, FrankfurtIf inflation doesn't rise over the next few years, it won't be for want of trying. Last year the Federal Reserve moved to average inflation targeting — meaning it could happily allow the rate to be higher than its official target of 2% for protracted periods. And on Thursday, judging by a briefing from officials in Frankfurt, we can expect the European Central Bank effectively to follow it. According to my colleagues who cover the ECB, the bankers agreed "to raise their inflation goal to 2% and allow room to overshoot it when needed." For the last two decades, the target was "below, but close to, 2%," which some policy makers felt was too vague. ECB President Christine Lagarde will unveil the full results of the bank's strategic review, and then give a press conference at 2 p.m. Frankfurt time. There are many reasons to criticize the ECB, but failure to meet its inflation target isn't one of them. Core euro-zone inflation last exceeded 2% in 2003. Thanks in large part to the sovereign debt crisis, the ECB has kept inflation lower than in the U.S. since 2011:  Any change matters because the ECB is the practical and spiritual heir of the Bundesbank. Owing in part to cultural memories of hyperinflation in Weimar Germany, and the horrible consequences, the ECB has always been far more militantly focused on eradicating inflation than other central banks. While its new strategy will probably still be more conservative than the Fed's, it appears to be moving in the same direction, giving itself wiggle room to buy more assets and intervene further in markets and the banking system to jolt the region's economy back into action. We are now at a point where all the world's most powerful central banks, which are charged with maintaining the strength of their currencies, now actually want to raise inflation, and have announced that their ideal rate is higher than it used to be. We also have a world recovering from the pandemic after much government money has gone toward stimulus. Money supply has never increased during peacetime in the way it has over the last 18 months. And we have the highest consumer-price inflation in decades. So, of course, on the eve of the ECB announcement, the market seems to have given up all belief in the "reflation trade." In the U.S., real 10-year yields fell below -1% on Wednesday at one point — a level that suggests utter insouciance at the prospect of inflation. Such easy financial conditions are all the more remarkable in coming as actual inflation has spiked:  Last month, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell talked up the chances of taking action earlier to head off inflation. The minutes from that meeting, published Wednesday, implied that any aggressive moves weren't imminent. Uncertainty around the economic outlook was "elevated" and it was too early to draw firm conclusions, according to the minutes, a statement with which it is impossible to disagree. There has also been a steady downgrading of estimates on the pace of the recovery, albeit from levels that were obviously unsustainable. The Atlanta Fed's "Nowcast" suggests that economic growth has dipped to 7.8%. That's its lowest in three months — but still very high for people to decide that negative real yields are appropriate:  Let's Assume ReflationIt's in markets' nature to overshoot. For those who remain convinced that a recovery and inflation lie ahead, therefore, this looks like a generous opportunity to re-enter. Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing, used to refer to "Mr. Market," an insane and paranoid individual who would every so often give you the chance to buy at a great price. Mr. Market is now offering an obvious opportunity to buy value stocks. Companies that look cheap compared to their fundamentals tend to do well in good times, as growth is easy to come by and investors are more anxious to seek out bargains. Value had been performing well since the first successful vaccine tests were announced last November. But now, in the U.S., its performance relative to growth has dropped below its 200-day moving average again:  There is also, just conceivably, more of an opportunity for stock-pickers, and for smaller companies. For much of the last five years, the market had grown steadily narrower as the equal-weighted version of the S&P 500, in which the largest and smallest members all account for just 0.2% of the index, dropped further behind the market cap-weighted version. This was driven by investors flooding into the biggest internet platform groups. During the first blush of enthusiasm for the reopening trade, that changed. Now the equal-weighted index is lagging badly again. This re-narrowing offers opportunities for those with conviction:  Finally, there is the barbarous relic, gold. Over the long term, the relationship between gold and real yields is clear-cut, and logical. Gold produces no income. The lower the yield on alternative investments, such as bonds, the more appealing gold will be, and vice versa. There are many false correlations in finance, but this isn't one of them. Real yields are inverted on this chart:  Hugely negative real yields should be great for gold. But that isn't happening. After the June Federal Open Market Committee meeting, real yields rose and gold fell, which is exactly what we would expect to happen when a central bank announces that it's about to get serious. But since then, gold has gone sideways while real yields have reversed their rise, and then some:  If you believe in the arguments for reflation, it looks like gold is a good idea at present. What's Going On?Journalists are often accused of offering too many neat narratives and spurious causations. There's truth in this; but we only do it because there is demand to explain what's happening. Humility is in order. The pandemic created a shock to the global economy unlike any other, and we lack precedents for understanding how recovery will work. Anybody who says they know what's going to happen is deceiving themselves. There are too many possible outcomes for anyone to be confident. You should hedge any bet. I read a lot of research. Here are some of the best summaries I've seen. I'll admit I don't know the answers, but these passages may help find some order amid the chaos. Louis Gave of Gavekal boiled down four broad scenarios for the coming months: 1) The world does not reopen fully and supply chain disruptions persist. Against this backdrop, governments continue to spend massive sums (printed by central banks). Aggregate demand continues to outstrip aggregate supply and so inflation proves more resilient than central banks, or the markets, currently expect. The probability of this scenario is significant.

2) The world reopens fully as vaccines and improved treatments reduce hospitalization and mortality rates even though infections may rise again. Demand surges on the back of strong consumption and a rebound in capital spending. The world faces a textbook case of twin demand both for consumption goods and for the capital goods to produce the consumption goods. Inflation remains high as supply struggles to keep up with roaring demand. Currently, this appears to be the most likely scenario.

3) Even though the world does not fully open again, governments pull back on the massive stimulus they have promised. Demand disappoints, putting prices under pressure. Inflation rolls over. This is the scenario that the market has started to price in over the past few weeks following the US Federal Reserve's guidance, the scaling-back of President Joe Biden's stimulus plans, and … the growing perception that [various central banks will soon start to tighten].

4) Governments continue to stimulate. But as the world reopens, supply catches up and overtakes rising demand. Of all these scenarios, this is the least likely, if only because of the dearth of capital spending over the last year and the rise in protectionism.

This sets out the problem very clearly. My own gut is that 1) had been overpriced and is now underpriced, and that 3) is currently overpriced. Jason DeSena Trennert of Strategas Research Partners offers this exhaustive list of possible explanations for the fall in yields: 1) relative bond yields; 2) faith in the Fed; 3) liability-driven investing; 4) expectations that the economic pain from the pandemic is far from over; or 5) distortions in the reverse repo market resulting in a run on Treasuries. In sooth, we know we don't know, but we're still expecting higher yields.

Again, I'm inclined to agree. Then there is the imponderable issue of the labor market and wages. Something strange is going on, with lots of vacancies and persisting high levels of unemployment. Robert Griffiths of Credit Suisse Group AG in London offered this thought: Probably the most telling part of [Tuesday's] ISM services release (which fell short of expectations, and drove a fresh leg lower in yields) was the following quotation from one respondent: "Some locations cannot open for business or (have) limited hours, as we cannot staff the restaurant to meet consumer demand." The number of people in work in the US is still 7.5m below its 2019 peak: you can always find workers, you just have to pay them enough. But for now, companies would rather cut output and stop operating than pay what is necessary to open up their businesses, perhaps because at the marginal wage required to open, they simply wouldn't make any money.

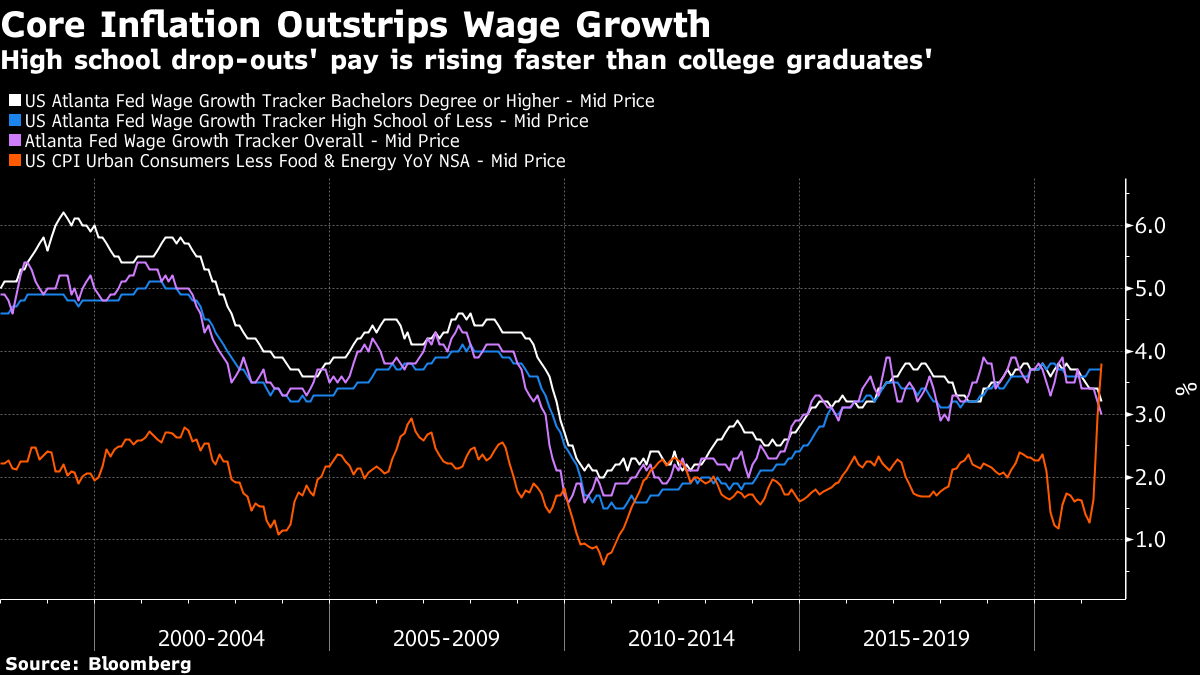

Griffiths doesn't use the word, but this sounds like an argument for the risk of stagflation. Reopening threatens to be expensive. Wage growth statistics are distorted by the pandemic shutdown, but the Atlanta Fed's trackers suggests something remarkable is afoot. Overall wage growth is down to 3%, but gains for those with no more than a high school diploma are exceeding those for college graduates by the greatest amount on record. At the same time, wage growth for everyone is behind core inflation, for the first time since the Atlanta Fed started keeping the statistics. Whatever is going on, this cannot last.  Griffiths opines that firms are betting, "probably correctly," that the worker shortage is temporary. That's creating a reluctance to pay more now. Firms will either have to push up wages to satisfy demand, driving a potential inflationary spiral, or hold back on expectation that conditions will normalize, he says. Either outcome leads to an economic mess that persists well into next year at least. My final offering comes from George Saravelos, strategist at Deutsche Bank AG in London: The market initially attempted to explain the moves via technical drivers and commentary has now shifted to a near-term growth scare. We disagree with both explanations. We think the single most important driver of the moves are persistent and rising global excess savings as well as a pessimistic reassessment of medium-term trend growth encapsulated in low real neutral rates, or r*.

For the uninitiated, r* is the real interest rate at which the economy can sustain full employment, without overheating or contracting. A lower r* means potential growth has declined. What brought us to this point? Saravelos offers three reasons: - A big turn in fiscal policy — Biden's honeymoon is over, and further growth will rely on the private sector.

- A big turn in vaccine efficacy — the one-off improvement is over; now attention is turning to the risk of persisting smaller Covid waves.

- The end of the V — the huge percentage improvements based on "catching up" after the pandemic are now over.

I hope these ideas help to frame discussion. Now, over to Frankfurt. Survival TipsSport can soothe the savage brow. England are through to the final of a major tournament for the first time in my life. They were decidedly lucky to win the penalty that won the match, and the behavior of some English fans was embarrassingly bad. I take no great pleasure in the defeat of the Danes, who had a great team representing a wonderful nation. But I'm not inclined to apologize. England have been the better team in every game they've played (except the one against Scotland), and they deserve their chance in the final. We can think of the final confrontation with Italy as a duel between theme tunes for two tournaments in which England lost semi-finals (unluckily) to Germany: Nessun Dorma, as sung by Pavarotti in 1990, and Three Lions, a 1996 song that appears to have been adopted as a new national anthem. Chances like this don't come around often; best to enjoy them. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment