A Lost WeekShould we all have taken the past week off? Last Wednesday, the Federal Open Market Committee's regular meeting produced a notable shift in a hawkish direction, which was confirmed in the later press conference given by Jerome Powell, its chairman. In a departure from previous communications, he speculated that unemployment, not inflation, might prove transitory. There followed a sharp fall in bond yields, and in inflation breakevens, while stocks gave up ground. On Monday afternoon, the Fed released the testimony that Powell intended to give to Congress on Tuesday afternoon. That was immediately perceived as moving the Fed's rhetoric in a dovish direction — in other words, less worried about higher inflation. That impression was broadly confirmed when Powell came to answer questions. This time, he continued to argue that unemployment was transitory, but also said that "we're digging out from a deep hole" with "a long way to go." That might be an argument for tightening, except that Powell was very clear that he expected inflation to come down without great intervention. While accepting that inflation had increased notably in recent months he said that it was "expected to drop back toward our longer-run goal" as transitory supply effects abate. My colleague Steve Matthews, the Fed reporter, offered these takeaways, which were almost exactly what traders alarmed by last week's events would have wanted to read: While Powell didn't break a lot of new ground, the thrust of his remarks in his prepared text and in the Q&A was quite dovish on monetary policy and supportive of continued aid. The chair saw inflation as transitory, due to supply issues and reopening of the economy, and urged patience before judging that price pressures are here for the longer term. Powell dismissed the idea of 1970s-style inflation -- when it went higher than 10% -- as "very, very unlikely," in part because the central bank is committed to its average 2% target. At the same time, he stressed that the exact timing of price pressures' waning is uncertain. He said the labor market has a long way to go and needs continued support, adding that the process of filling job openings can take time. Job growth is likely to be strong in coming months and has been held back by a number of factors, including people worried about Covid, school closures, the time needed to find a job, and unemployment benefits.

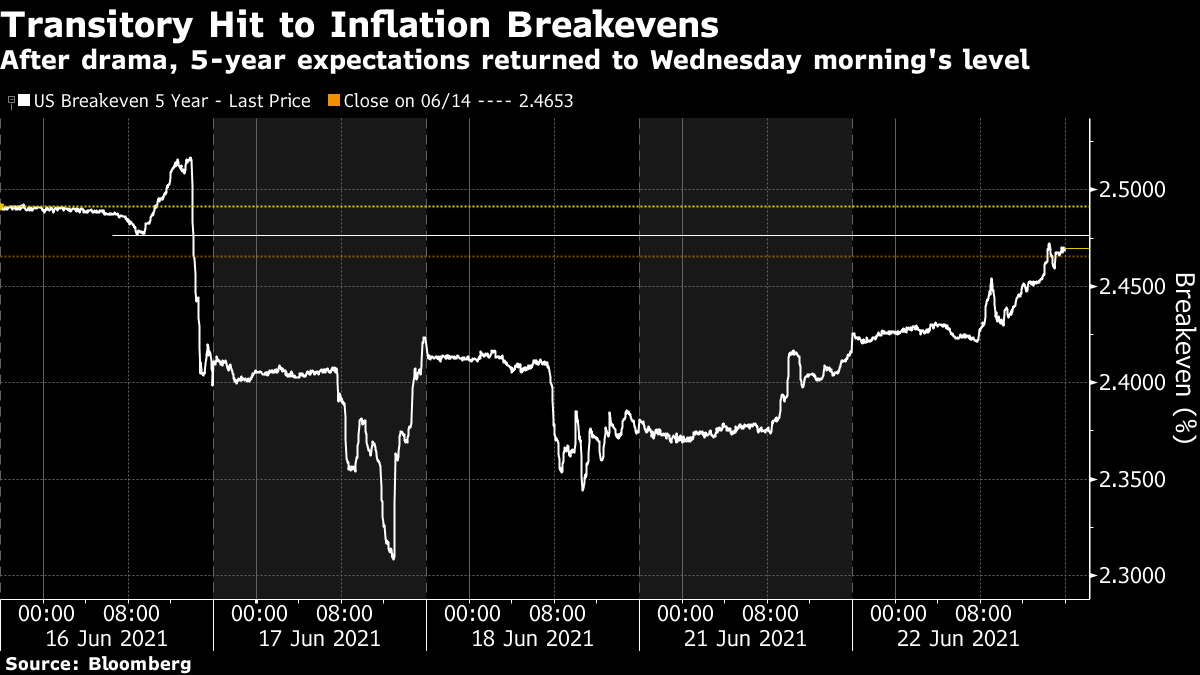

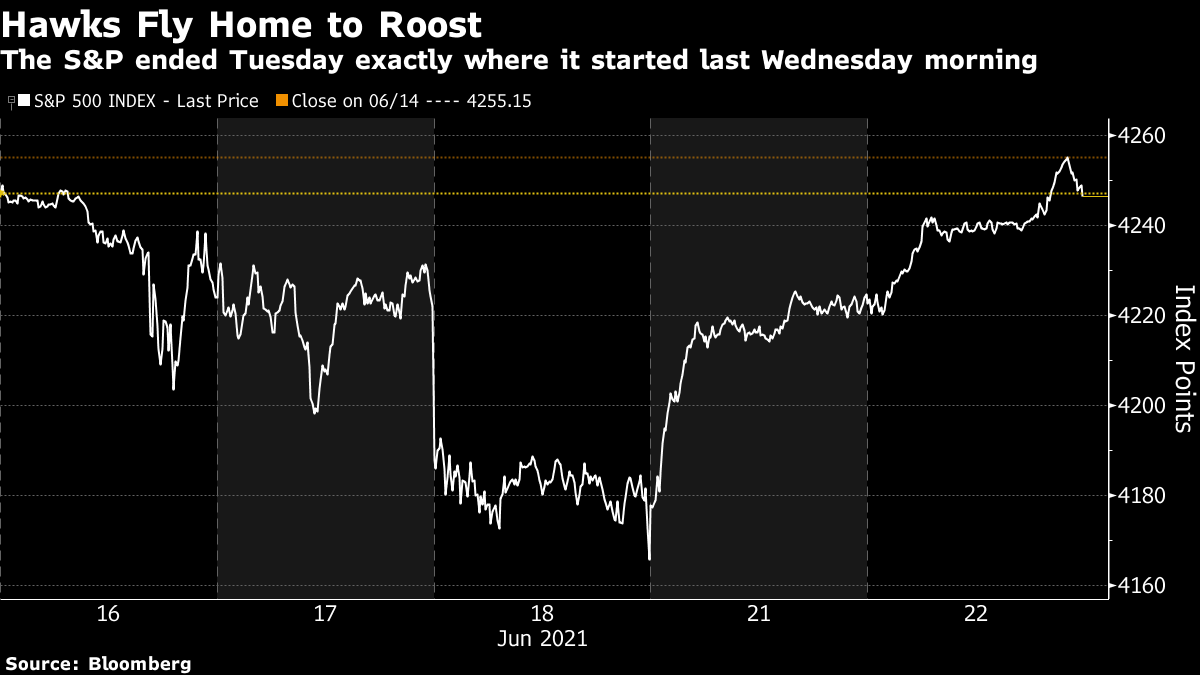

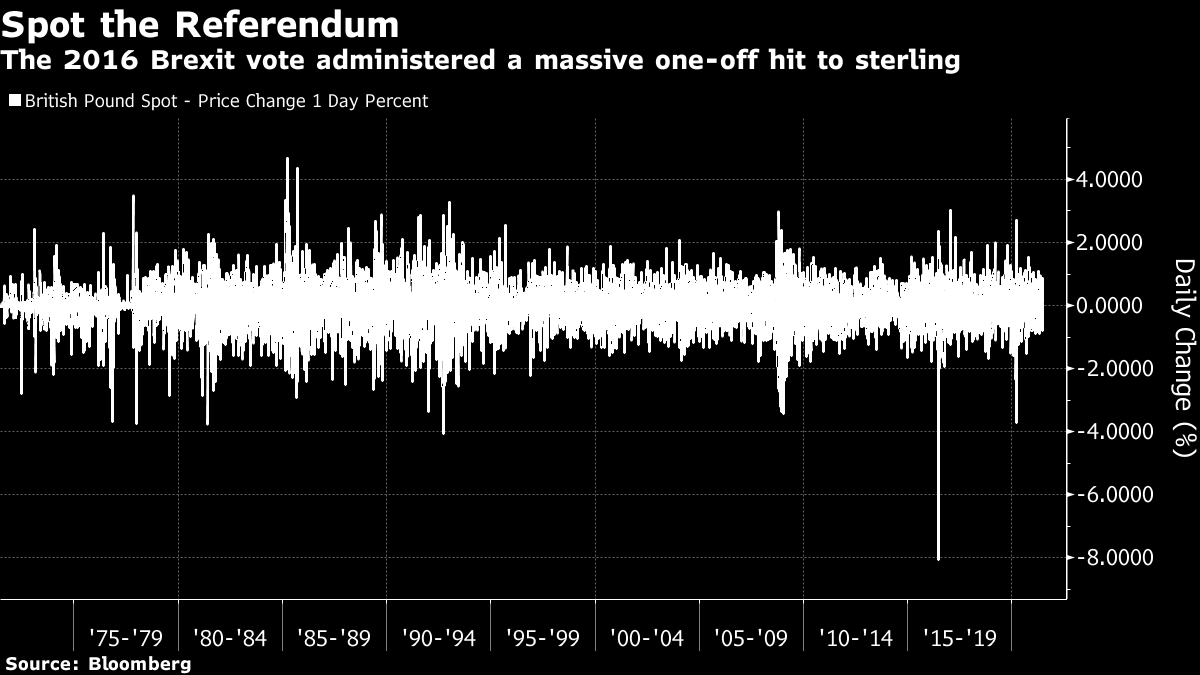

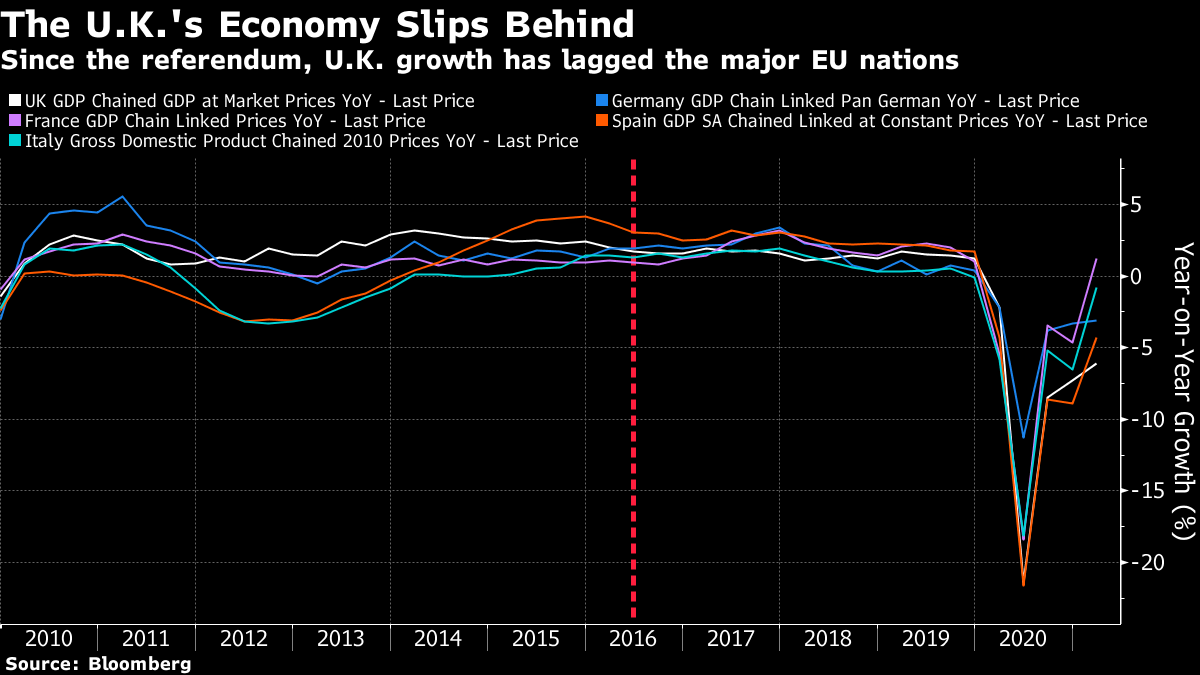

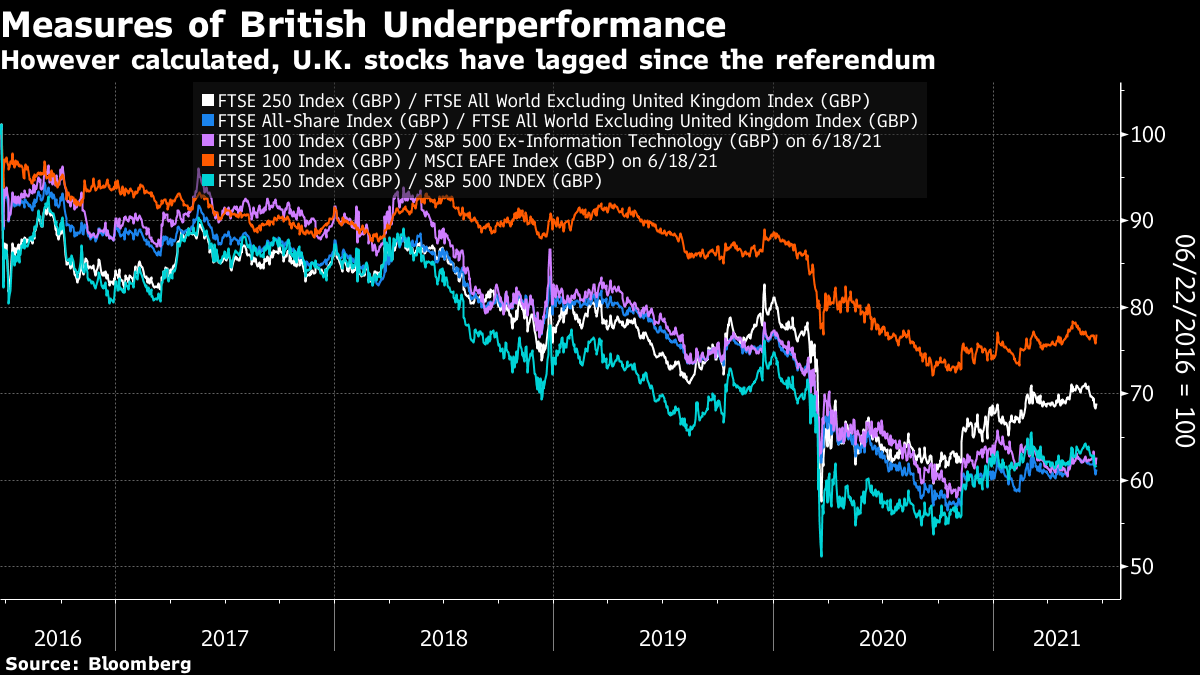

The result of all this was one of the market's most perfect round trips you will ever see. The dip in five-year inflation breakevens has been, for want of a better word, transitory. As of 4 p.m. Tuesday afternoon, they were almost exactly where they were at 9 a.m. last Wednesday:  The round trip in the stock market was even more perfectly executed. As of 4 p.m., it had moved exactly 0.0% since the opening last Wednesday, according to Bloomberg.  Digging further, the Bloomberg Factors To Watch function reveals that the momentum factor has also gained exactly 0.00% over the last five trading days. A shift from value (-1.17%) to growth (+0.98%) does however remain intact. That might have more to do with Powell's congressional inquisitors than the Fed chairman himself; declining confidence in a federal infrastructure spending splurge translates into lower confidence that cheap stocks will have enough growth to beat those with more reliable earnings gains. In other markets, the dollar weakened a bit Tuesday afternoon, but is still holding on to most of last week's rally. Commodities made some progress, but remain weaker than they were before the FOMC. What should we make of this? One cynical interpretation, with which I started, is that we could all have taken the last five days off. Traders and the commentariat (like me) need something to keep things moving, to give us a chance to say something interesting, or to provide an excuse to buy and sell. In this case, the symbiotic relationship between minute-by-minute traders and commenters has yielded sound and fury signifying nothing. Another explanation is to blame the Fed. Powell should have guarded his words more carefully. What were all the Fed governors thinking with their predictions anyway? One explanation is that the dot plot looked more hawkish than Powell had expected, with the result that his mild rhetoric came across as more hawkish than it would have done against a less scary backdrop. But there's no need to be so cynical. We've never been in this place before, with ridiculously low interest rates and an economy that still hasn't shrugged off all the effects of a global pandemic. Powell and his colleagues need to gauge reactions and opinion, which means trial balloons. Markets need to be confronted with different scenarios and see where there is demand and supply. Ultimately, the Fed wants to guide a gentle and slow path toward something like normality. Nobody's been hurt. A few people made some commissions, and I filled some column inches, and at the end of it all we had moved a tiny way forward on the path that Powell is trying to navigate. But still, five days of such excitement and speculation and all it got us was a 0.00% return on the S&P with 0.00% momentum? It's hard not to laugh. June 23 is the fifth anniversary of Britain's Brexit referendum. As a reminder, the U.K. voted to leave the European Union, 43 years after joining. Exit, in formal terms at least, finally came about early last year just as Europe and much of the rest of the world was about to succumb to the Covid-19 pandemic. It's way too soon to judge whether it's actually paid dividends for the U.K. and its economy. Even the most ardent Brexiteer wouldn't expect any great change by now. It's also too soon to say whether economic pain has been averted. Neither side of the divide, which was about far more than macroeconomic and trade policy, can claim to have been proven right, and neither has been decisively proven wrong. With the revised trade deal between the U.K. and the EU only coming into force at the beginning of this year, clarity will have to wait. But when it comes to global market resiliency, the referendum provided a stress test that the system passed. Arguably, the pound took the biggest one-off devaluation for a major currency in the 50 years since the floating currency regime started in 1971. This is a chart of the pound's one-day moves against the dollar. I think you can spot referendum day:  Hedge funds had, for reasons that remain mysterious, placed big bets on the pound (and therefore on a victory for "Remain"), and suffered great pain. The risk that an incident like this could create cascading losses in an over-connected system was obvious and led to an immediate spike in volatility, while investors seeking havens took the 10-year Treasury yield to what was then a historic low. But that spike soon subsided. In Europe, volatility on the Stoxx index, the equivalent of the U.S. VIX, topped out near the level reached during the Chinese devaluation of the previous summer. It didn't reach that height again until the pandemic. The VIX rose but the moment was seen as less dangerous than other shocks in the years before Covid-19.  As for the snap judgment that traders made in the New York night and the early hours of the London morning, it has stood up remarkably well. Sterling's devaluation persisted, and the currency has never — on a trade-weighted basis — exceeded the level at which came to rest on the day after the referendum. The market proved capable of accurately moving the currency down instantaneously from one trading level to another, without serious further shocks:  That cheaper level has buoyed British competitiveness at a time when Brexit uncertainty might have scared trading partners away. In the last five years, U.K. growth has been slightly slower than for the main EU nations, which were lagging in the years ahead of 2016 thanks to the euro-zone sovereign debt crisis. But it's hard to say that there's been a disaster:  On stock markets, however, there has also been a clear judgment. Whichever way you look at it, British stocks have badly lagged behind relevant international benchmarks since the referendum:  Whether using the FTSE-250 (a mid-cap index which is most directly exposed to the U.K. economy), or the broader FTSE All-Share, or the FTSE-100, which tends to be dominated by mega-cap banks and materials companies, and whether comparing with the rest of the world, the U.S., or the developed world outside the U.S., the bottom line is that the U.K. has underperformed by at least 20%. I continue to think that Brexit was a bad idea. It may well yet lead to further destabilization in Northern Ireland and Scotland. But broadly the market discount has been applied, and Brexit has now happened. On the morning of the referendum, the FTSE All-Share traded at just over 17 times prospective earnings, and the S&P 500 at just under 18. Now, the All-Share's prospective P/E is just below 15, while the S&P's is 22.5. The FTSE-Eurofirst 300 was slightly cheaper than the U.K. five years ago; it now trades at 17 times next year's earnings. Brexit is more than priced in now. It's probably created a nice long-term buying opportunity for British shares. The Words of Jeremy GranthamMany thanks to Jeremy Grantham for giving us more than an hour of his time Tuesday morning, and fielding a number of difficult questions. Thanks also to all those who submitted questions. I don't have space to write about Grantham's comments, but I urge you to read Kriti Gupta's neat summary here. The bottom line is that he thinks meme stocks are "the biggest fantasy trip ever." You can also find the whole thing on ALIV on the terminal. Two memorable moments for now include first this analogy about the reduction in the speed with which liquidity is accumulating: Just as bull markets turn down when confidence is high but less than yesterday, so the second derivative determines the effect of liquidity. The best analogy is the fun ping-pong ball supported in the air by a stream of water. The water pressure is still very high and the ball is high, but the ball has dropped an inch or two.

That analogy explains a lot. I suspect we'll have to return to it. And as for his confidence that we are witnessing a bubble that's about to burst (a confidence that, as several readers pointed out, has not been great for his company's investment performance of late) he said this: For the great bubbles by scale and significance, we also noticed that they all accelerated late in the game and had psychological measures that could not be missed by ordinary investors. (Economists are a different matter.) The data, like today, is always clear, just uncommercial and inconvenient for the investment industry and often psychologically impossible to see for many individuals.

He's still confident. Comments welcome.

Survival TipsSoccer continues to provide the goods (or at least England looked much better against the Czech Republic than they did against Scotland), but I've been asked what was so great about Antonin Panenka's penalty that won the 1976 European Championship for Czechoslovakia. After all, all he did was tap the ball forward as the goalkeeper made a despairing dive. That was the whole point. The literature of behavioral finance is full of "activity bias" — the feeling that we ought to do something, and that doing nothing is more embarrassing than trying and failing. There is money to be made out of other people's activity bias. Many years ago, I wrote up a paper on activity bias by James Montier (who by coincidence works these days for Grantham's firm GMO), in which he took soccer goalies as an example. Slaves to activity bias, they always dive one way or another. This means that most of the time, a striker with the confidence of Panenka can score just by lobbing the ball straight in front of him. To make the save, all the goalie has to do is stand still, but they don't. To hit such a penalty, the striker has to overcome his own activity bias. Having a penalty saved is bad; having it saved by tapping it straight in front of you must be mortifying. Just as it takes nerves of steel for a goalie to stand still, so Panenka needed nerves of steel even to think of doing what he did. And it worked. So that's a survival tip; let's all try to have the confidence of Antonin Panenka and conquer our activity bias. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment