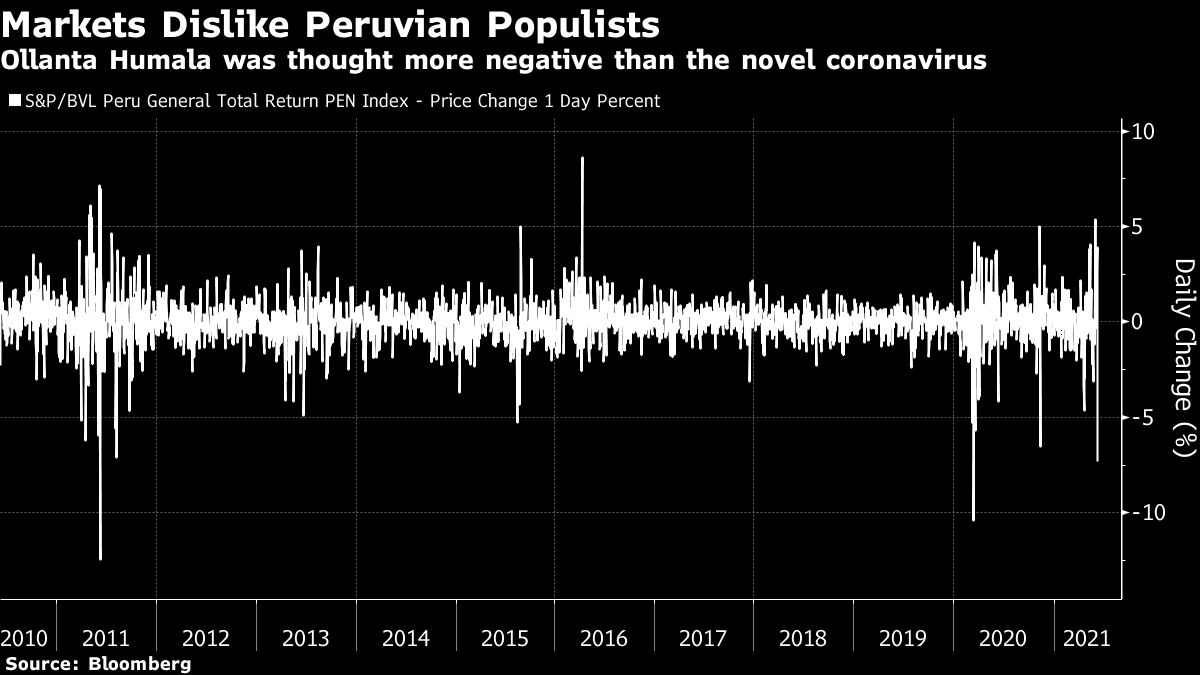

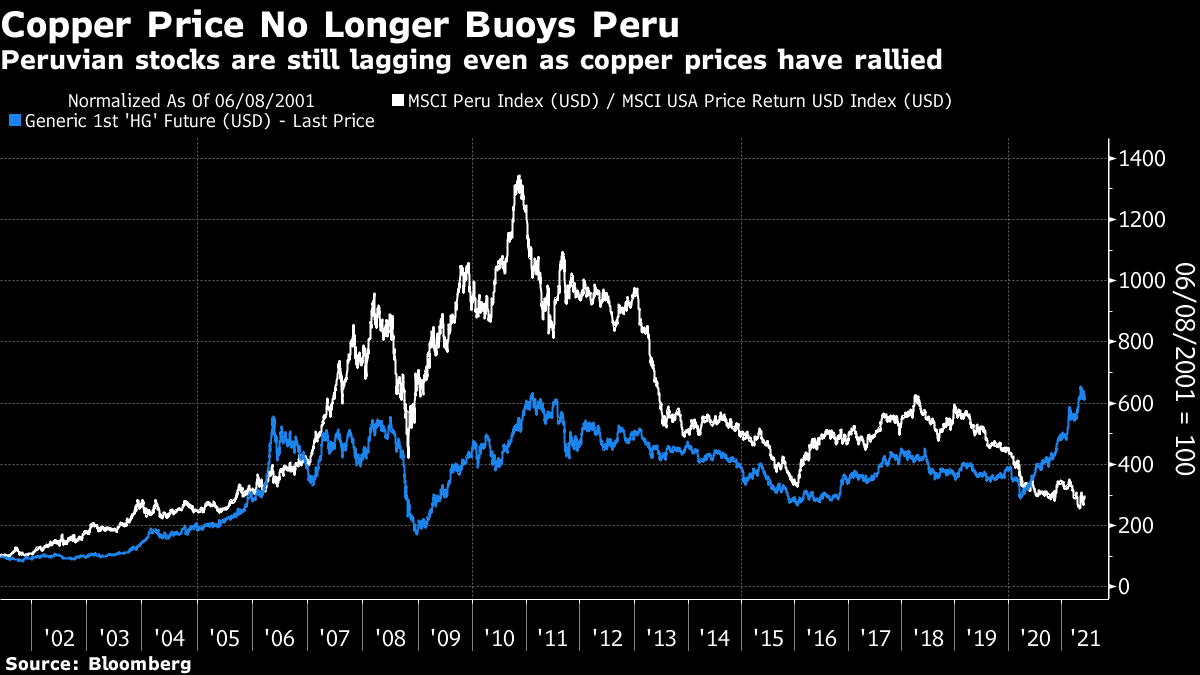

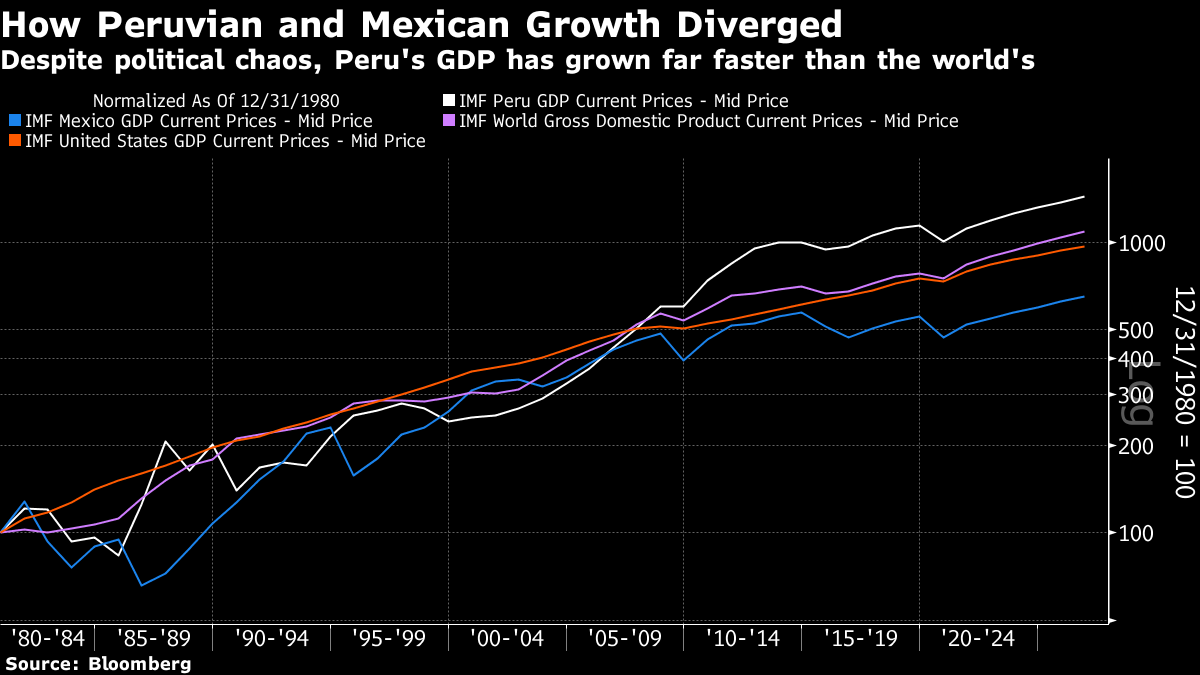

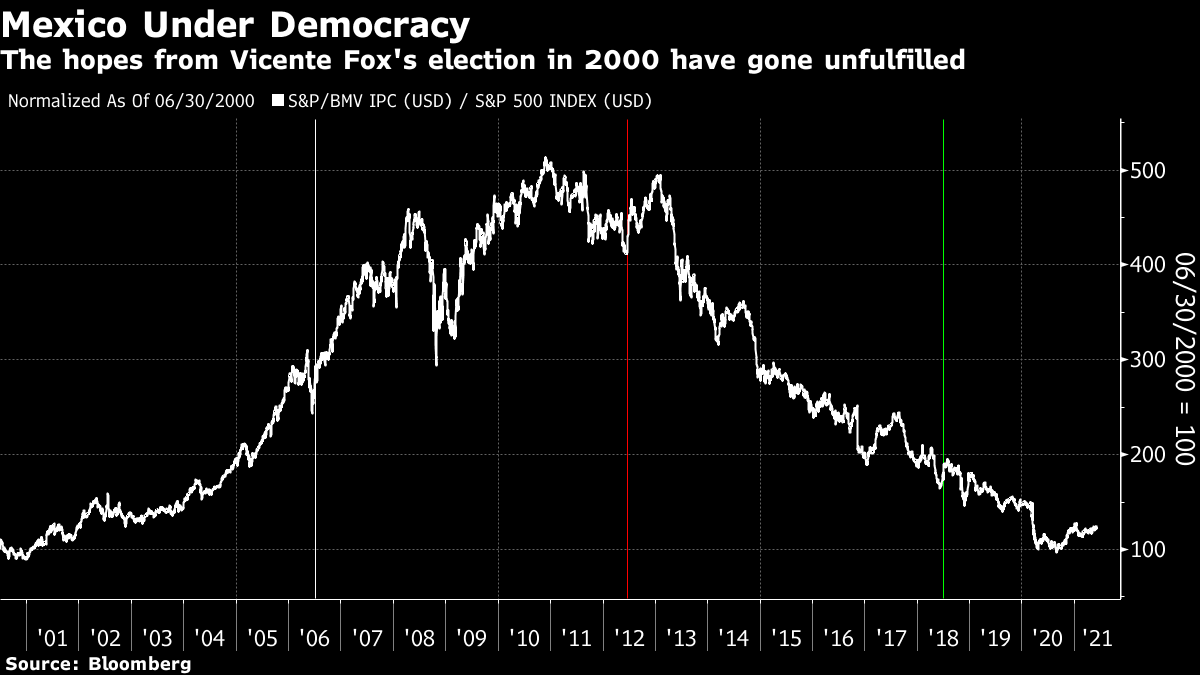

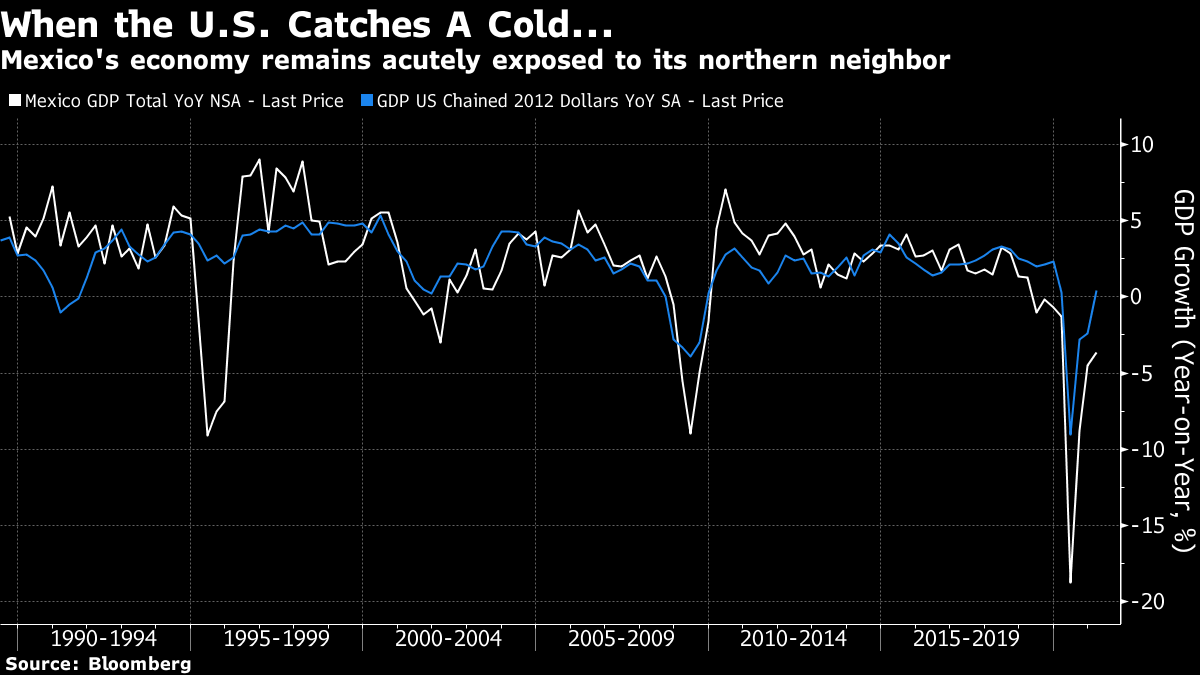

Latin ElectionsOn a day of market torpor, the drama was reserved for the ancient lands of the Incas and the Aztecs. Both Peru and Mexico held elections Sunday. Peru appears narrowly to have chosen the leftist Pedro Castillo as its president, while Mexicans in sweeping mid-term elections clipped the powers of left-wing President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (known as Amlo) somewhat, by denying him a super-majority in the lower house of Congress. There was no question how equity investors felt about this. Mexican stocks gained almost 2% on a day of nondescript returns elsewhere; Peruvian stocks tanked by some 8%:  This was one of the most brutal selloffs the Peruvian stock market has seen in decades. Outside of a few of the worst days of the pandemic last year, we need to go all the way back to June 2011 for a worse day, when Lima's stock exchange fell more than 11%. The only snag is that the plunge was caused by the election as president of another populist left-winger, Ollanta Humala. That selloff proved to be a buying opportunity; within a month the market had rebounded by 20%. Humala didn't do much to deal with Peru's intractable problems while in office, but he didn't impede steady economic growth either. His arrival was even more unwelcome to the stock market than the appearance of the novel coronavirus, but he turned out to be far less damaging:  Humala's election was only one of many examples of markets taking fright at the election of a Latin American populist, only to find their bark worse than their bite. Hugo Chavez and Nestor Kirchner showed in Venezuela and Argentina the lasting damage that a populist leadership can do; Luiz Ignacio Lula da Silva demonstrated in Brazil that it isn't that simple. Meanwhile, several reformist, market-friendly presidents have proved very disappointing. Enrique Pena Nieto in Mexico and Mauricio Macri in Argentina were greeted as economic saviors but failed to turn around the problems they had inherited. The depressing conclusion is that the politics of Latin America matter less than external factors. In the case of Peru, its fate is unhealthily tied to China, which has a continuing demand for its metals. Over the last two decades, Peruvian stocks massively outperformed even the U.S. for a while, but then came back to earth, moving almost entirely in line with the global copper price. What is unsettling is that the copper rally of the last 12 months hasn't helped spark a revival for equities. Investors were evidently more skeptical, even before Castillo won the presidency:  But at least Peru has managed to grow its economy persistently over the last 40 years, and it has done so despite politics that seem to come straight from the pages of a magical realist novel (indeed, in 1990 the country nearly elected Mario Vargas Llosa, a magical realist novelist and great admirer of Margaret Thatcher, as its president). Humala served for five years. Since the last presidential election, in 2016, Peru has had four presidents, plus another acting one. It also witnessed the suicide of a two-time former president as he was about to be arrested. And despite this basket-case, failed-state political record, Peru has enjoyed the stablest economy in the region. Taking GDP as a criterion, it emerged from the Maoist insurgency and hyperinflation of the 1980s to produce growth that far outstripped the world and the U.S. Meanwhile, Mexico (which started from a higher base) has conspicuously lagged the rest of the world:  Mexico spent seven decades under one-party rule, and aroused great hopes when the election of Vicente Fox in 2000 at last broke the hold of the oligarchic Institutional Revolutionary Party. Looking at the stock market, investors were evidently excited for a decade, and were even glad to see Pena Nieto, a member of the old ruling party viewed as a reforming technocrat, take power in 2012. In terms of market performance, however, Mexico's underperformance has been unremitting after a brief dose of excitement. Amlo didn't speed up that decline, but did nothing to slow it down:  Mexico's particular privilege, or curse, is to neighbor the U.S. (The old saying goes that Mexico is "so far from God and so close to the USA.") Since 2016, the election of Donald Trump, Amlo's victory two years later, Trump's defeat last year, and now the mid-terms have all been greeted as big deals. Trump and Amlo were seen as inevitably at loggerheads. In the event, immigration has continued to be a big issue in the U.S., but the Nafta trade deal was renegotiated with minimal changes, and the dramatic political shifts have left the Mexican peso barely any weaker than it was in November 2016, when markets were trading on the assumption that Hillary Clinton would take power:  All the while, Mexico's political class has diligently done all the things that the International Monetary Fund and the rest of the global financial community asked of it in the wake of its disastrous devaluation crisis in late 1994, which ended with more than half the country's banking assets being written off. Mexico's record in battling inflation over the last quarter-century has been remarkably successful:  The problem is that the country's economic orthodoxy has done nothing to reduce its dependence on its powerful neighbor. In the early 1990s, Mexico managed to keep growing as the U.S. suffered a minor recession. The 1994 meltdown was self-inflicted (with an assist from surprisingly high interest rates in the U.S.) Since then, every U.S. slowdown has been matched by a far worse decline in Mexico. And unfortunately, it finds itself in competition with China as a provider of cheap labor, rather than as a provider to it like many of the countries to the south. So whenever the U.S. catches a cold, Mexico contracts pneumonia:  Amlo is a true-believing left-winger, but he is also conservative (with a small "c"), instinctively frugal, and pragmatic. It was predictable from the moment when he set out his economic program for his run for the presidency (in an interview with me, as it happens), all the way back in 2005) Mexican economic orthodoxy has continued under his watch. Markets were evidently relieved to see his wings clipped a little in the mid-terms. But for good and ill, he has remained broadly true to the stall he laid out 16 years ago: "Inflation and instability affect the poor the most, since they have no way to defend themselves," Mr Lopez Obrador says. "In the case of Mexico, those who have benefited most from the crises are those with the most resources. The better off have more ways to defend themselves." A government led by him would run the economy in "a technical rather than an ideological way", he says.

That has been a recipe to avoid disaster, but also for continuing nagging underperformance. For all the excitement of Latin American politics, the truly consequential politicians, such as Chavez, have proven to be the exception rather than the rule. That implies that there may well be another buying opportunity in Peru before long. It also implies, with aching frustration, that the region's fate is still determined more in Beijing and Washington than by its own voters. Chile: A Long, Thin PostscriptFor one country where politics have made a huge difference to markets in the last couple of years, go to Chile. Like Peru a huge copper producer, it had risen and fallen with the metal's price in this century. Formerly an oasis of political and economic stability, the world was shocked when it erupted in violence in late 2019. The sharp fall for Chilean stocks is visible in the chart. Since that moment, Chile's stock market has underperformed the U.S. by some 50%, despite the gain in the copper price:  What is happening in Chile is genuinely exciting. A referendum last year determined that its constitution, adopted under the Pinochet dictatorship, should at last be rewritten. Last month, the voters chose a startlingly left-wing and populist group of politicians to oversee that rewrite. And stock markets liked that not one little bit. Chile's voters are trying to take their fate into their own hands. The evidence from the rest of the region is that international markets may not let them do that. Survival TipsThis tip is also by way of a personal request. Medical research helps us all. And the experience of the last year, when long investigation into the abstruse world of mRNA proved invaluable in speeding the development of a Covid-19 vaccine, shows that research is seldom wasted. Some areas may seem less important than others, but they always matter. About a decade ago, I discovered the hard way that the pancreas remains one of our least-understood organs. I was hospitalized with acute pancreatitis, a misfortune that has befallen me a few times since. I don't recommend it. But what has been interesting about being a patient has been to discover how much there is still to learn; a large proportion of pancreatitis cases remain unexplained (like mine), and much of the research into the pancreas is tied to pancreatic cancer, which remains the most deadly of all cancers. At a pragmatic level, however, the medical profession is getting much better at alleviating the effects, and for this I am very thankful. It hasn't stopped me from having a career. During my medical adventures, I discovered that there is relatively little in the way of funded medical research into problems of the digestive tract. The whole field tends to be something of a Cinderella. (If any brilliant biotech venture capital investors out there would like to get involved, that sounds great to me, and I've just declared my interest!) Somehow, those explorations have ended up with my becoming a pitch man. Those of you in Britain will next week have the chance to hear me give an appeal for the charity Guts UK on BBC Radio 4. All the details can be found here. I don't profit myself (of course), but if you have the time to give it a look, or even the funds to give it some money, I'd be very grateful, and so would many others who've been less lucky than me. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment