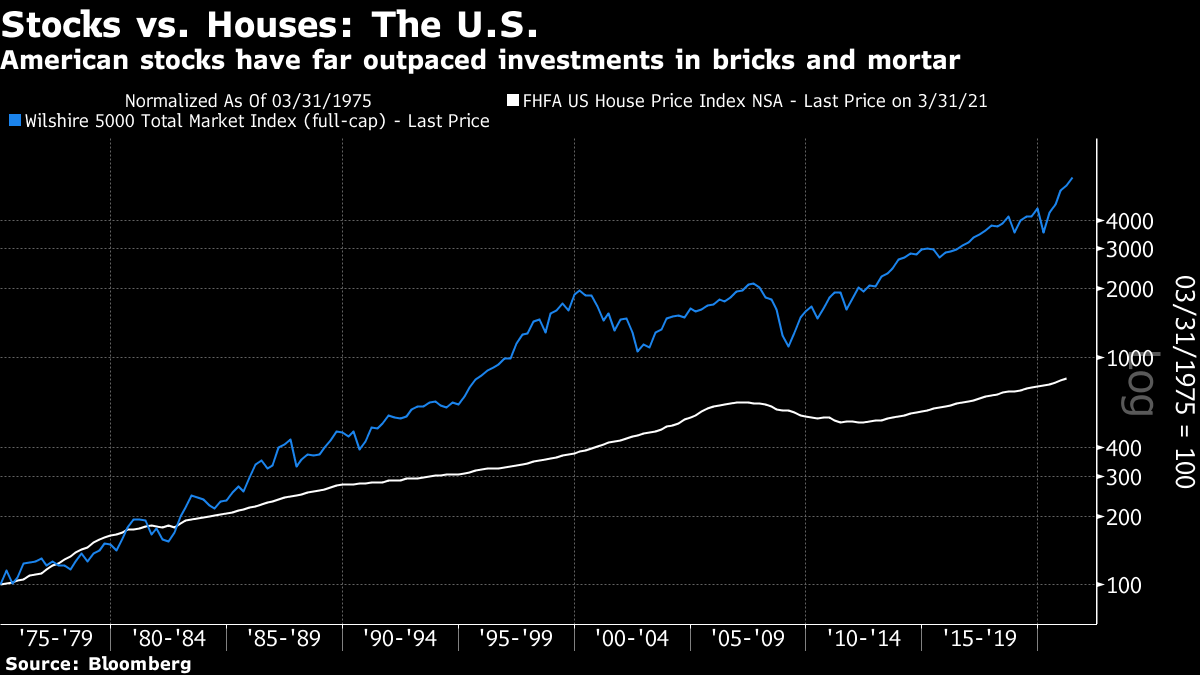

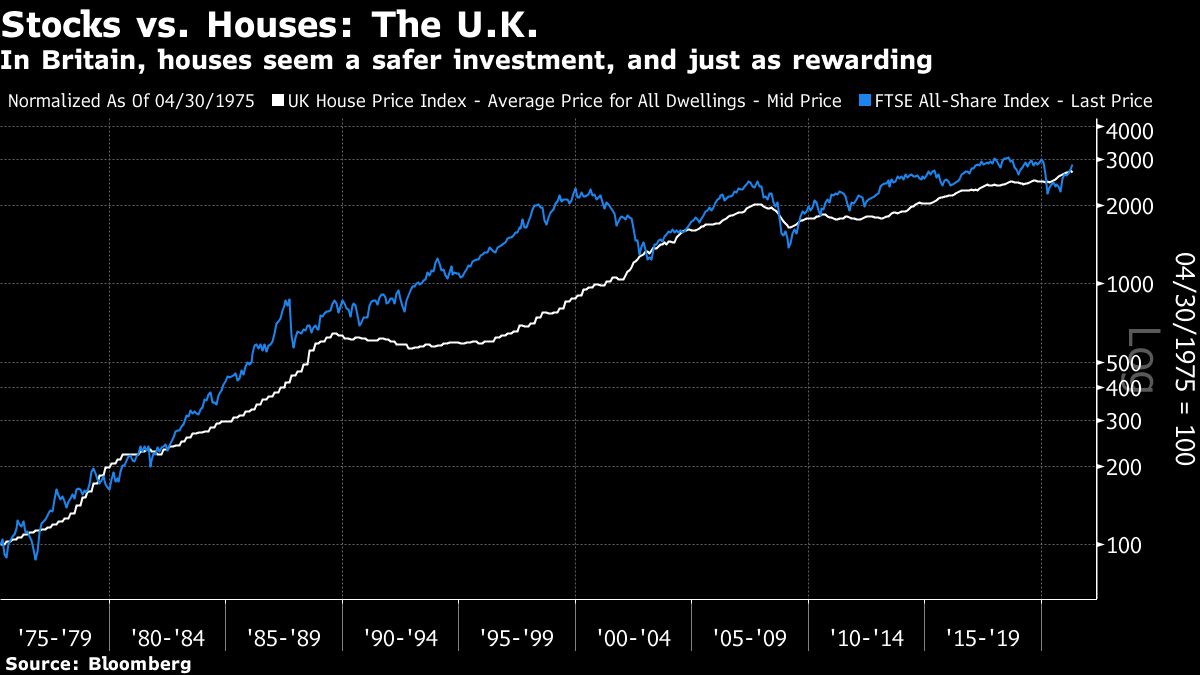

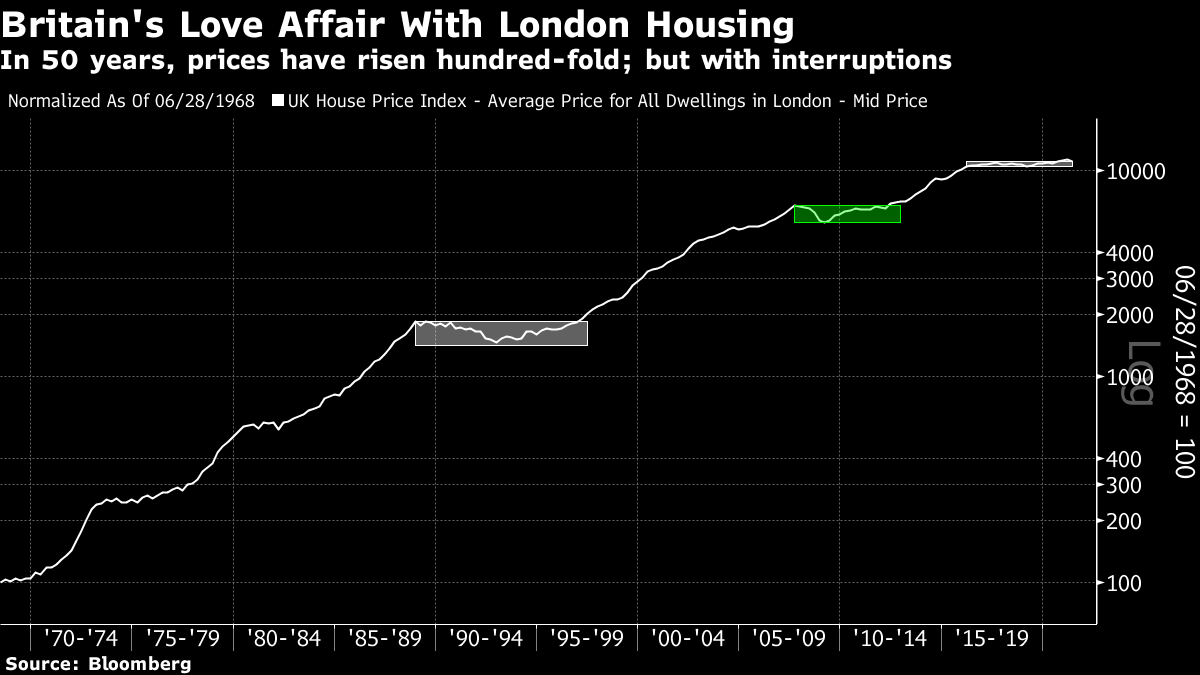

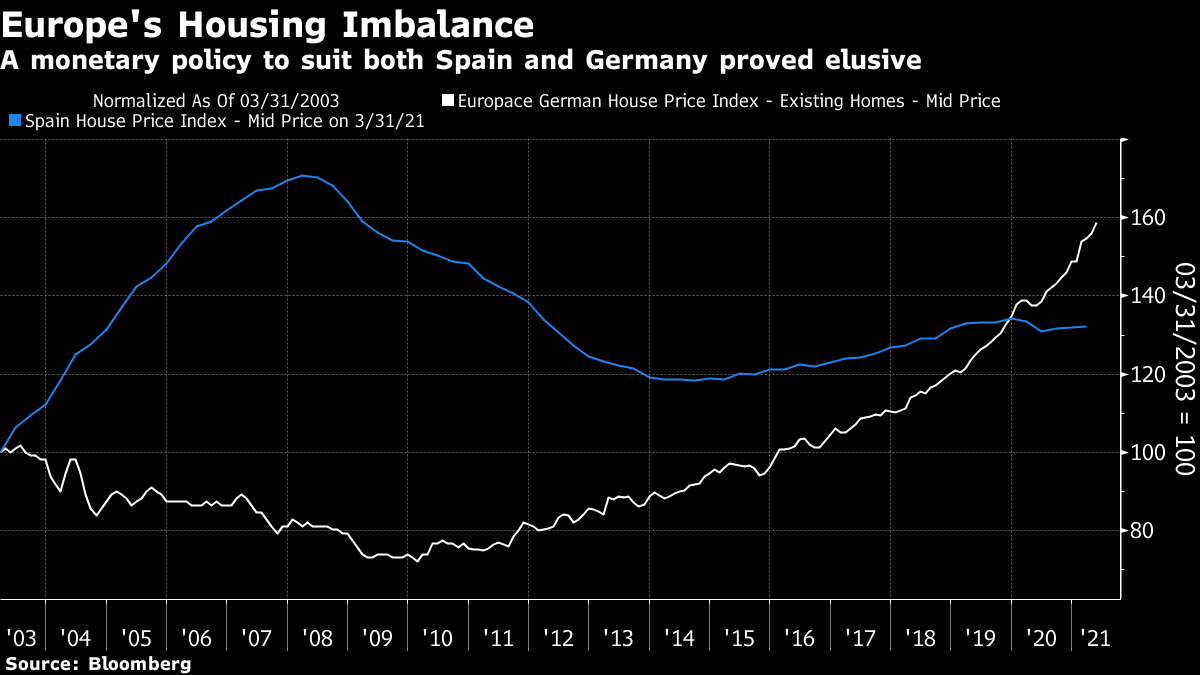

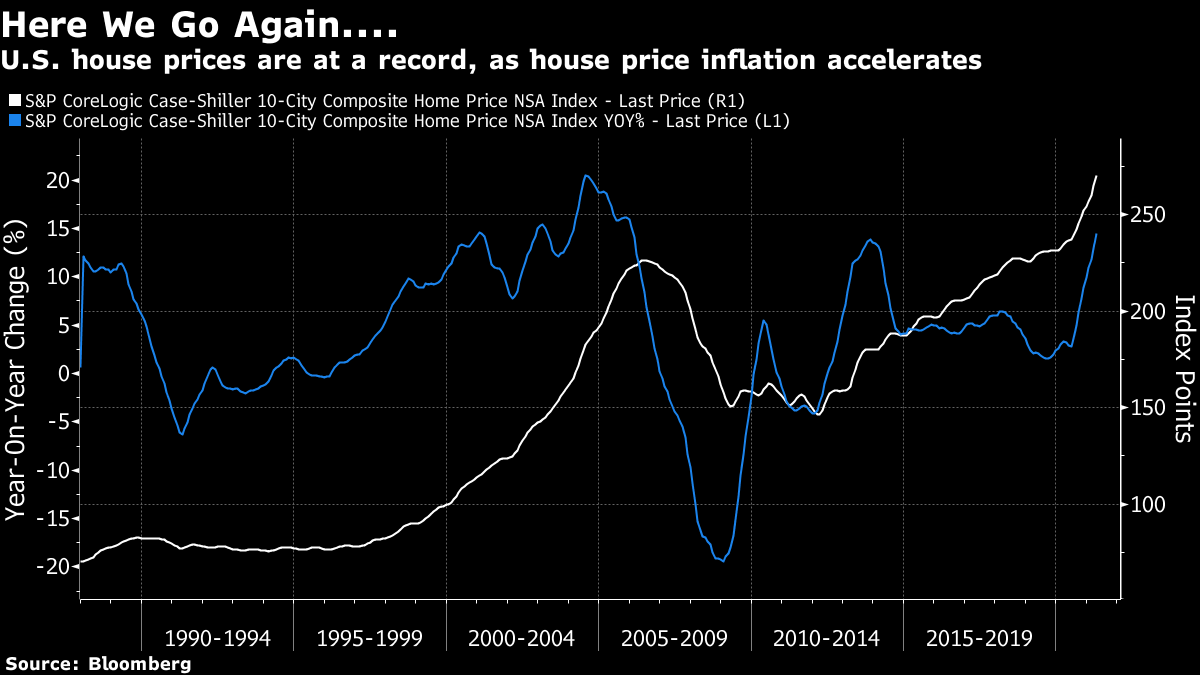

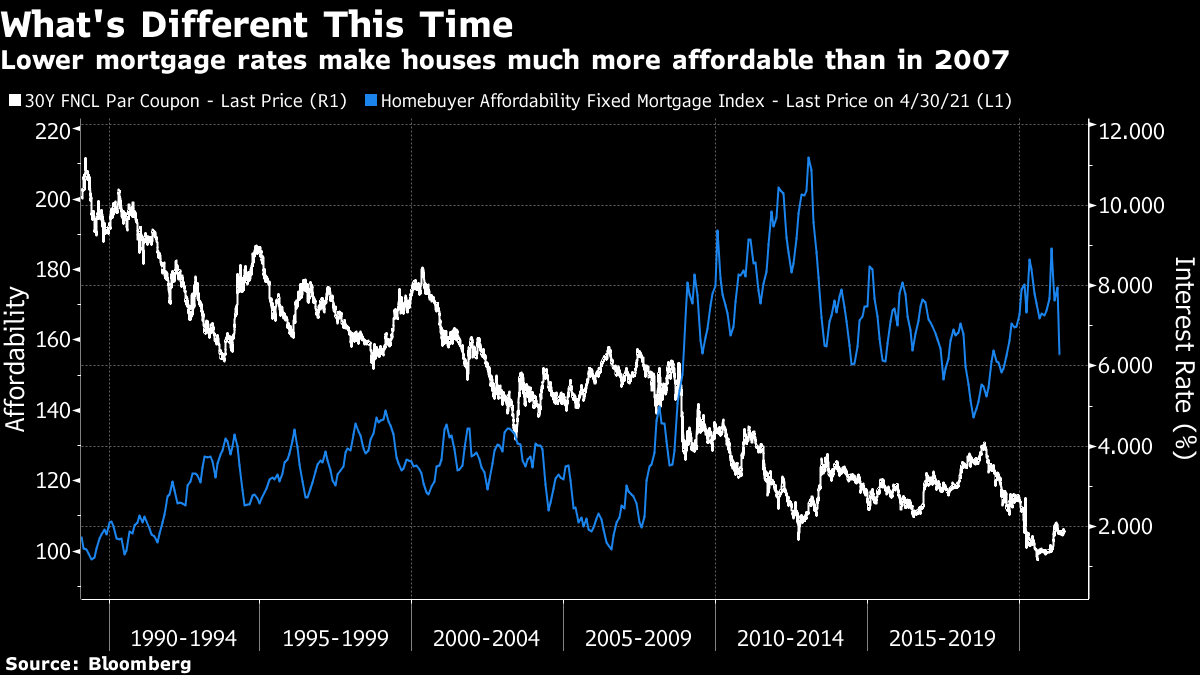

An Englishman's Home Is His Castle (and His Debt Burden)As I've grown older, I've learned to keep my temper in public. I've also managed to control the bad habit when younger of ridiculing people when I thought they were being stupid. There are advantages to growing up. But when it comes to housing, all bets are off. A few years ago I was speaking about the bond market at a conference in London. When it came to Q&A, a young man in his 20s stood up and asked me why anyone would invest in stocks these days, like the baby boomers once did. Wasn't it obvious that stocks and bonds weren't to be trusted? Younger people knew that the only safe investment was in real estate. How could I justify telling people to do anything other than buy a house? He was well-spoken and obviously intelligent. My immediate reply was that that was the stupidest comment I'd heard in years; could he please confirm that he wasn't being sarcastic? He did, and I proceeded to ridicule him. I shouldn't have (sorry, out there, if you're reading this). However, I still think it's important to stamp out such nonsense. We all need a place to live, and a house can indeed be a great investment, but over the decades I've seen misbegotten love of property create far more pain than any stock market infatuation. And the British are particularly susceptible. It's a disagreeable foible, much like the national obsession with the England football team (which many of my unfortunate colleagues know about after seeing me watch England play Germany in the Bloomberg newsroom). Americans think I'm mad when I say they aren't obsessed with housing the way the British are. Americans are, after all, obsessed by house prices. But it's true. Brits have never taken to the stock market with anything like the same excitement. They tend not to think of themselves as budding entrepreneurs or Warren Buffetts. But they all seem to be convinced that they can make a killing in real estate. To some extent, this is because of experience. Here is how houses have performed compared to stocks since 1975 in the U.S.:  Stocks have been a massively superior investment, as might be expected. Companies can grow with the economy in a way that houses cannot. Here is the same exercise for the U.K.:  In the U.K., housing and stocks have enjoyed much the same appreciation over the long term, but property has given a far less bumpy ride. And, of course, you can live in a house, but not in a share certificate. British home prices have also far outperformed those in the U.S. (almost as spectacularly as American stocks have beaten the blue chips of the U.K.) In part this is due to supply issues. Land is far easier to come by in the U.S. But there is also a particularly British presumption in favor or owning rather than renting, and a continuing predilection of politicians to curry favor by pumping up the market. While there is a peculiar Britishness to the excitement over London home prices, the psychological problems with real estate are universal. For most of us, a house will be the biggest purchase we ever make. It's important, and it's public. People can see where we bought, and we will spend much of our lives there. We zero in on the price, because it has been the focus of vital negotiations. Most of us can remember the prices at which we bought and sold every house we've had. In the psychological jargon we "anchor" on these prices, and this leads to apparent massive gains. We tend not to think of the interest expense, or the repairs, or taxes, or all the other costs involved, and we don't annualize returns and compare them to gains that might have been made elsewhere. Nobody provides a regular statement with the latest percentage return as they do for a pension or a portfolio. Bricks and mortar therefore tends to seem a far better and safer investment than it is. There's another important difference about housing investments; leverage is cheap and easy to come by. This means gains will be impressive compared to stocks; with an 80% mortgage, a 20% increase in price turns into a 100% return for you. But it also means that the potential downsides can be too easily ignored. Housing crashes are disastrous on the rare occasions when they occur because they cause leveraged losses for people who cannot afford them. With debt, a "crash" doesn't need to be so bad in price terms to have a severe effect. London house prices, for all their meteoric rise, have also had long periods when buyers could only sell for a loss — and having taken out massive mortgages, they were often in negative equity and couldn't sell at all. For much of the 1990s, people with growing families found themselves trapped in rabbit hutch-like London flats they had bought straight out of college to "get on the housing ladder." At times like this, fear of missing out can lead to lives going seriously awry:  To this we can add the political folly that elected representatives desperately want this not to happen, so they prime the market with subsidies and tax breaks. In Britain, at least, house prices are seldom allowed to fall much. That helps homeowners, but takes property ever further from the grasp of the younger generation, fomenting anger. And that leads an intelligent young man to regard housing as the ultimate safe investment. In Britain's economy, which has been rigged to help homeowners more than the capitalists who run companies, it's an understandable belief. But real estate can be dangerous. I'm going to get to the U.S., which has new house price data out, but next we head to continental Europe. Europe's Housing ImbalancesBritain has suffered much pain thanks to housing downturns. But perhaps the most calamitous outcome to an over-extended market has come in the euro zone. This is what has happened to house prices in Spain:  A boom so distended, followed by such a long bust, must have many causes. But it's worth focusing on the effects of the euro's adoption, beginning in 1999. The great monetary experiment started with Spain's economy already running hot, while Germany was still struggling to swallow reunification a decade earlier. With only one monetary policy, the new European Central Bank chose rates appropriate for Germany, the larger economy, which meant borrowing costs that were far too low for Spain. Investment funds flowed in from Germany and elsewhere in Europe, inflating an unsustainable Spanish construction boom. Then came the crash, Spain's financial institutions were left nursing loans with no chances of being repaid, and the euro-zone sovereign debt crisis soon went into full swing, extending the European leg of the financial crisis for many years. This is how Spanish and German house prices have compared:  It is only recently that German house prices have at last overtaken those of Spain. Property busts, when they happen, can cause deep and lasting damage. U.S. House PricesThat brings us to property prices in the U.S. S&P Case-Shiller data came out Tuesday, and showed a continuing sharp increase. Across 10 large cities, and on a national level, prices are now well above their peak before the global financial crisis. The FHFA home price index is up 15.7% from a year earlier, the highest rate on record. Whichever way we look at it, the market looks hot:  We know what happened after the last great peak, and nobody wants a repeat. However, as in many other market matters, today's exceptionally low interest rates change the picture. The benchmark Fannie Mae mortgage yield has fallen since the last crisis, in large part thanks to the determined efforts of the Federal Reserve. This means that affordability, defined by how easily someone on the typical income could cover the interest payment on a typical loan, remains unchallenging. Despite a dip in affordability recently, house prices are more manageable than they were at any point in the decade before the crisis:  While there is a lack of available homes, therefore, the rally could yet go further. Capital Economics Ltd. cautions as follows: These buyers will face strong headwinds this year. Annual house price growth surged to a record high… stretching affordability. Booming values have been accompanied by a sharp rise in house price expectations. That raises the risk of a self-reinforcing bubble forming, similar to that seen in the mid-2000s, as households look to take advantage of rising house prices. That could provide support to sales over the remainder of the year. But with lenders unlikely to significantly ease credit conditions over the next few months, we think a house price bubble and acceleration in sales is unlikely.

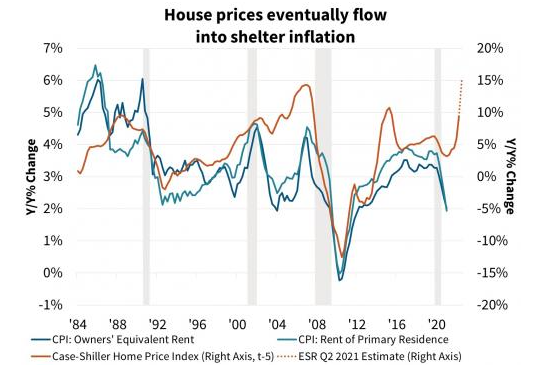

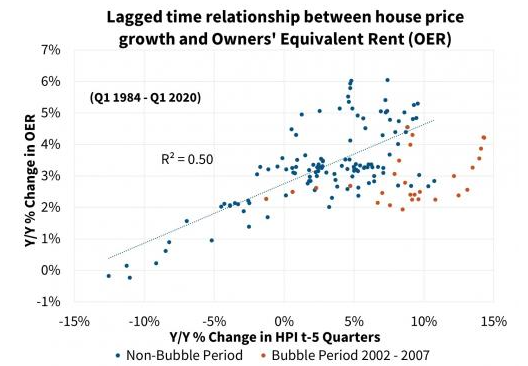

Without the crucial extra ingredient of irresponsible leverage, a housing bubble is much less dangerous. And if we look at another bubble indicator, money flows into homebuilding stocks, this incident is nothing compared to what happened 15 years ago:  A sharp rise in house prices always demands attention. But on balance this doesn't look like a destabilizing dose of speculation. But What About Inflation?This leads to the issue of the moment, which is inflation. Rising house prices actually increase the buying power of those who already own them, while the cost of financing more expensive homes causes families to cut back expenditures in other areas, so the effect is counterintuitively deflationary. Shelter is still the largest single component of the consumer price index, though. Via their impact on rents, higher house prices affect inflation, but with a lag. The following chart, from a rather sobering paper by Fannie Mae, suggests the CPI components for rents tend to follow the Case-Shiller price index with a delay of about five quarters:  When the property market is in a true bubble, and prices are higher than can be justified by the rental yield they could raise, the effect is less direct. That appears not to be the case at present. Excluding the "bubble" period from 2002 to 2007, the relationship is tight:  Eric Brescia, economist at Fannie Mae, makes these concerning conclusions: - due to how shelter costs are measured, the housing components of the indices decelerated considerably over the past year, despite strong home price appreciation. This has kept topline inflation from being even higher.

- Lagged effects from the past year's house price appreciation and more recent rent recovery could begin to flow into inflation measures as soon as the May readings. House price gains to date suggest an eventual acceleration in shelter inflation from the current rate of 2.0 percent annualized to about 4.5 percent. If house price growth continues at the current pace, shelter inflation would likely move even higher.

- Timing lags suggest increasing shelter inflation will last through at least 2022, meaning "transitory" increases to the rate of overall inflation may be more prolonged than many are expecting. Due to the heavy weight given to shelter, housing could contribute more than 2 percentage points to core CPI inflation by the end of 2022 and about 1 percentage point to the core PCE. Both would be the strongest contributions since 1990.

It would be stretching definitions to call this another housing bubble. But the natural human tendency to perceive housing as a more attractive investment than it is leads to the real risk of higher inflation than many now appear to expect. While this dose of housing inflation need not inflict the horrors of past bubbles, it could create problems if it carries on much longer. Survival TipsMaybe don't try writing rather a long and complicated financial newsletter while trying to watch England knock Germany out of an international soccer tournament for the first time since a couple of months before you were born, as I did today. But it was fun. Many congratulations to Ukraine for the remarkable way they beat Sweden at the death in Tuesday's other game. With few historical disputes between England and Ukraine, maybe the English can manage to be a little less chauvinistic before the quarter-final. Meanwhile, continuing last week's theme of the lessons that goalkeeping errors can have for investors, I should draw the first goal of the Spain-Croatia game from Monday to your attention. Here it is. The moral: Don't do whatever the investment equivalent is of standing with nobody anywhere near you and nonchalantly directing the ball into your own net. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment