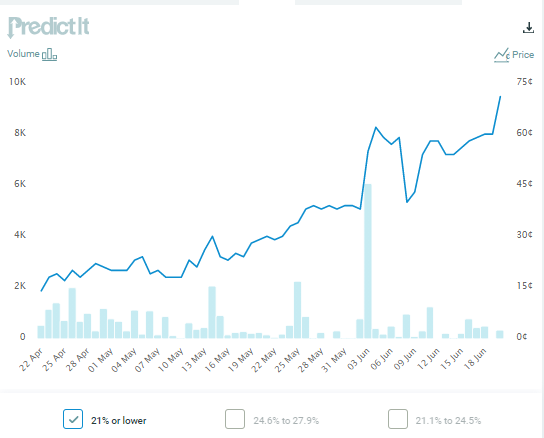

Is It the Liquidity, Stupid?Markets are still trying to work out what would be most comfortable in the wake of the Federal Reserve's shift in emphasis. After a big move away from the "reopening trade" at the end of last week, there was a return to it Monday, with stocks doing well, and bond yields rising a bit. The overall judgment that the latest Federal Open Market Committee meeting was bond-positive and stock-negative remains in place. The same sentiment applies to fiscal policy. After the Biden administration's startling success in pushing through extra coronavirus relief money in its first weeks, the attempt to follow it up with a big infrastructure package is getting bogged down in some complicated congressional horse-trading. Nobody wants to take responsibility for nixing it altogether, so some package still has a political chance, but the odds of a significant further fiscal push are definitely falling. With it, the chances of a corporate tax hike to pay for it are also receding. That might be good for the stock market in the short run, but it would also mean less government largesse. For some attempt to quantify this, here is how the likelihood that the corporate tax rate stays at 21% or lower for 2022 has moved over the last 90 days on the Predictit prediction market:  Dan Clifton, political analyst for Strategas Research Partners, similarly suggested that the odds of more infrastructure dollars had been trimmed back in recent weeks, with the chance of a corporate tax increase now at about 40%. But the chance of a tax cut four years ago, in the first year of the Trump presidency, seemed to have evaporated by the end of the summer. Clifton suggests that politics could still produce some more money before the year is out: the current stalemate over infrastructure is similar to the headwinds President Obama faced over Obamacare and President Trump faced over his tax cuts at this exact point in their presidencies. Both policy initiatives hit their lowest probabilities in mid-August. Upon returning from August recess, in both cases, Congress became more practical, lined up the votes, and passed their legislation in 4Q. In both cases, the policies had to fail before they could succeed. And the prospect of not passing legislation a year before the midterm election was a big catalyst for action.

So there is a chance for fiscal stimulus to return to the agenda. And Jerome Powell, chairman of the Fed, has the opportunity to put right any market misunderstandings on monetary policy when he speaks to Congress on the economic impact of the pandemic Tuesday morning. His prepared testimony, released in advance, seems to push the emphasis back toward arguing that current inflation is transitory: Inflation has increased notably in recent months. This reflects, in part, the very low readings from early in the pandemic falling out of the calculation; the pass-through of past increases in oil prices to consumer energy prices; the rebound in spending as the economy continues to reopen; and the exacerbating factor of supply bottlenecks, which have limited how quickly production in some sectors can respond in the near term. As these transitory supply effects abate, inflation is expected to drop back toward our longer-run goal.

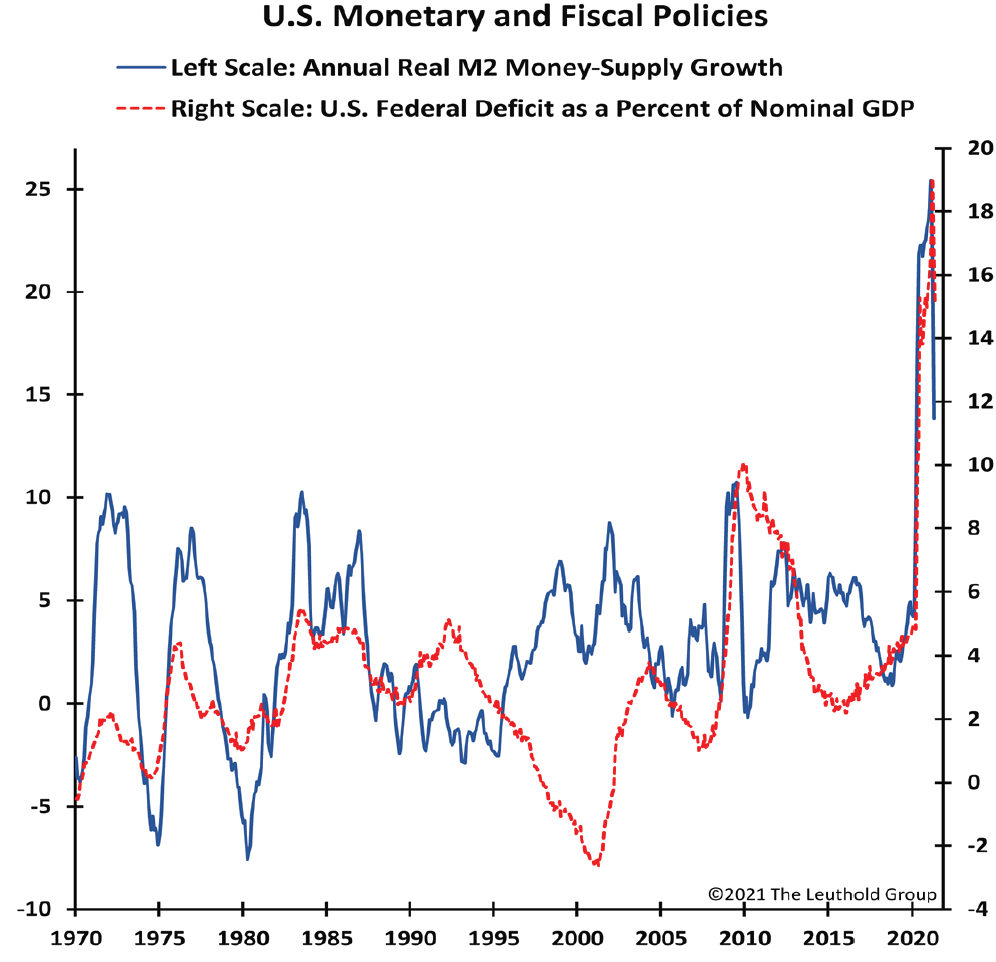

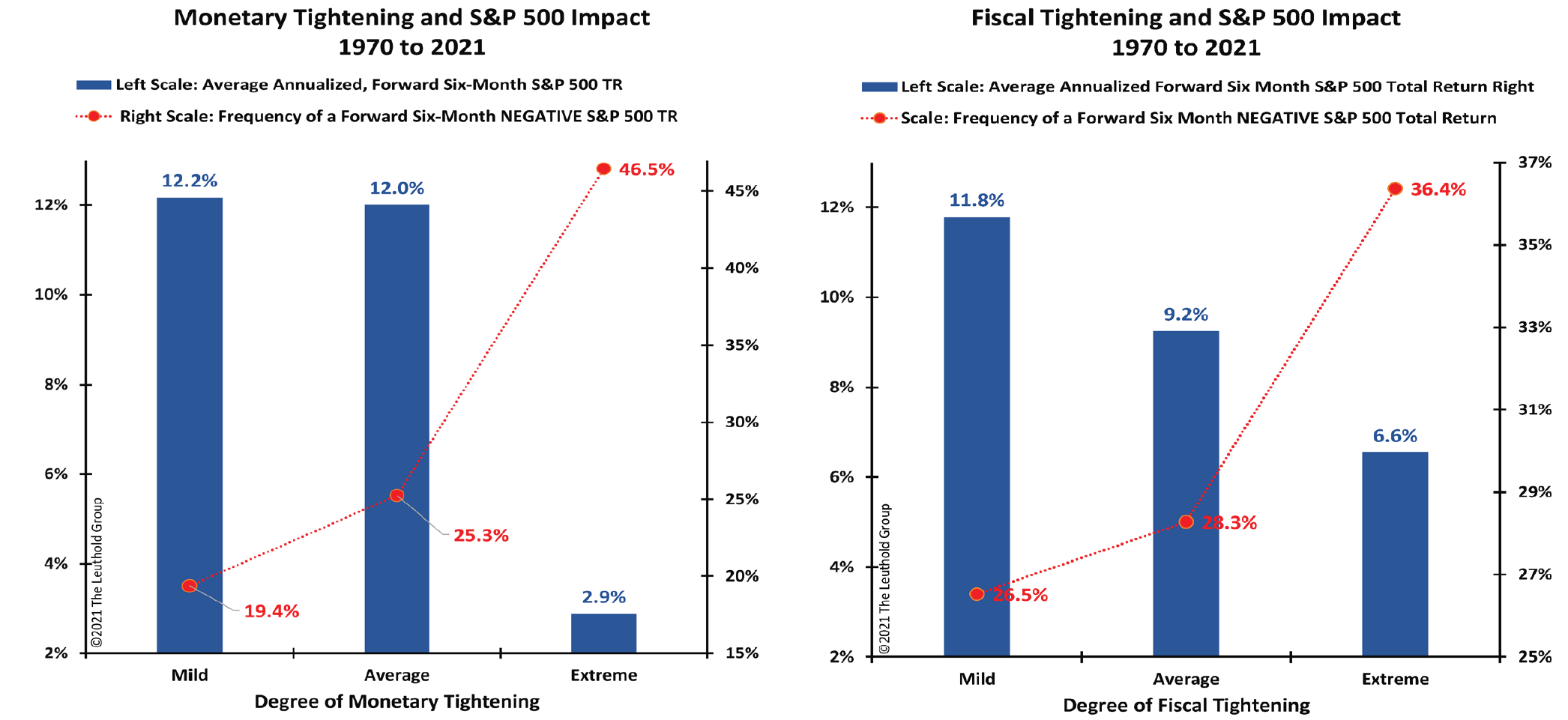

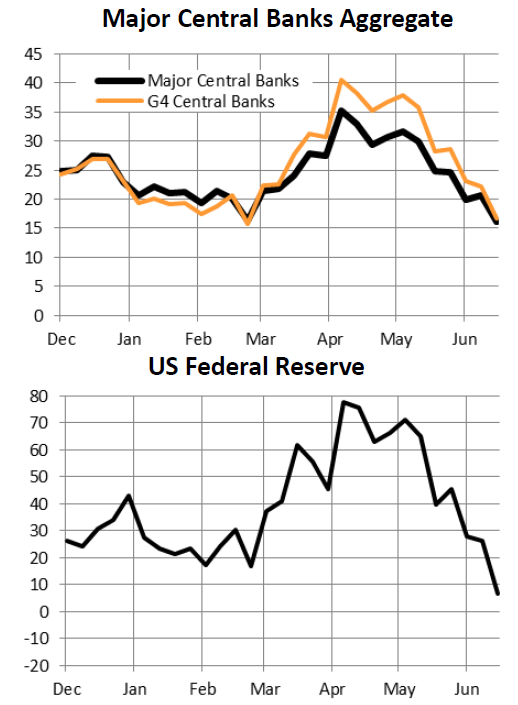

It's possible, then, that we've just seen an extreme pendulum swing in the market's judgment on what policymakers will do, and that it could soon swing back. Alternatively, it's possible to argue that the market was reacting not to Powell's words (although these sped up some movements that had already started) or to the depressing gush of talk from Capitol Hill, but rather to a trend in liquidity caused by the Fed's actions — and also by the actions or inactions of elected politicians. Rather than worry about when the Fed will formally taper off the purchases of assets it makes each month, it might make better sense to look at the actual trends in money supply growth and fiscal stimulus. Tapering, when it happens, will involve a reduction in the speed of the Fed's purchases, rather than an actual decrease in the assets it holds. In other words, it will be a "second derivative" change. This is often what matters most in financial markets. But if we look at the growth of money supply and the federal deficit in annual terms, we find that both are falling sharply. The change in the second derivative has already arrived, in a big way. This chart is from James Paulsen, chief strategist at Leuthold Group in Minneapolis:  Simple measures like this may be the best. With growth in new sources of money suddenly decreasing, Paulsen classifies both fiscal and monetary tightening as extreme — and just eyeballing the chart shows that this is about as fast as deceleration gets. On that basis, the odds of a forthcoming fall in the stock market become very significant:  On this reading, we had seen a gradual dawning in investors' minds that the speed of help for them was slowing down, which crystallized with last week's FOMC. To look at this in more detail, Crossborder Capital Ltd. of London keeps indexes of central bank liquidity growth globally. This shows a global deceleration, which is most marked in the U.S., and which uncoincidentally peaked roughly when bond yields topped out in early April:  The Fed isn't tapering its asset purchases, but it is far less directly involved in pumping money into the system through the repo market. Also, critically, this isn't being counterbalanced by a rundown in the Treasury General Account, which was built up in the early months of the Covid crisis to cover all eventualities. (I wrote about this complicated issue here.) As Crossborder Capital summarizes: U.S. monetary base growth has plummeted to 7%: it peaked at 78% only 10 weeks ago. It is driving the downturn in policy liquidity expansion. ECB and Bank of England liquidity growth also peaked in April but the downturn has been less pronounced. Meanwhile, the People's Bank of China, and now the Bank of Japan too, look to be moving in the opposite direction

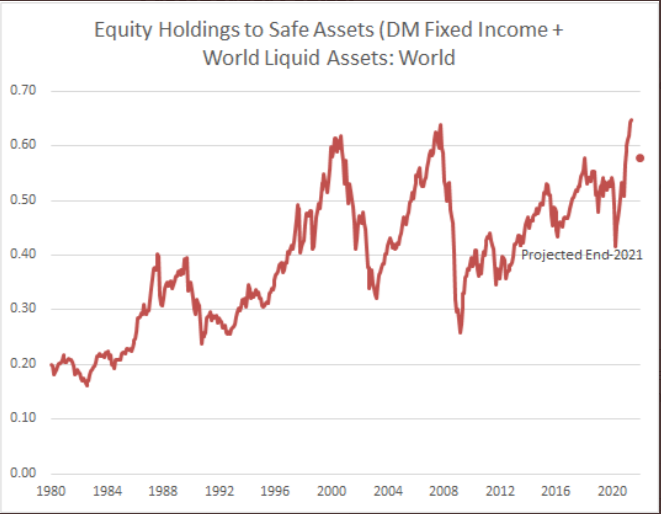

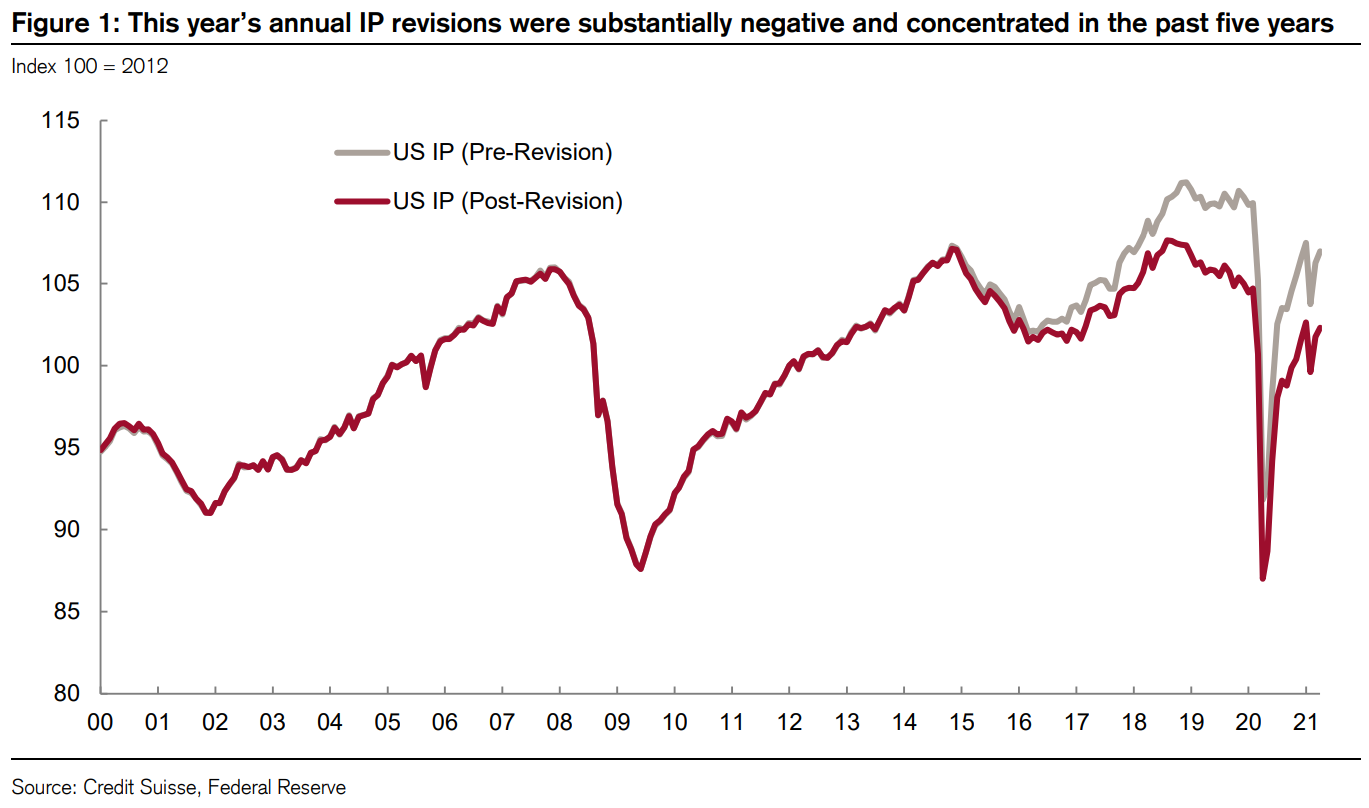

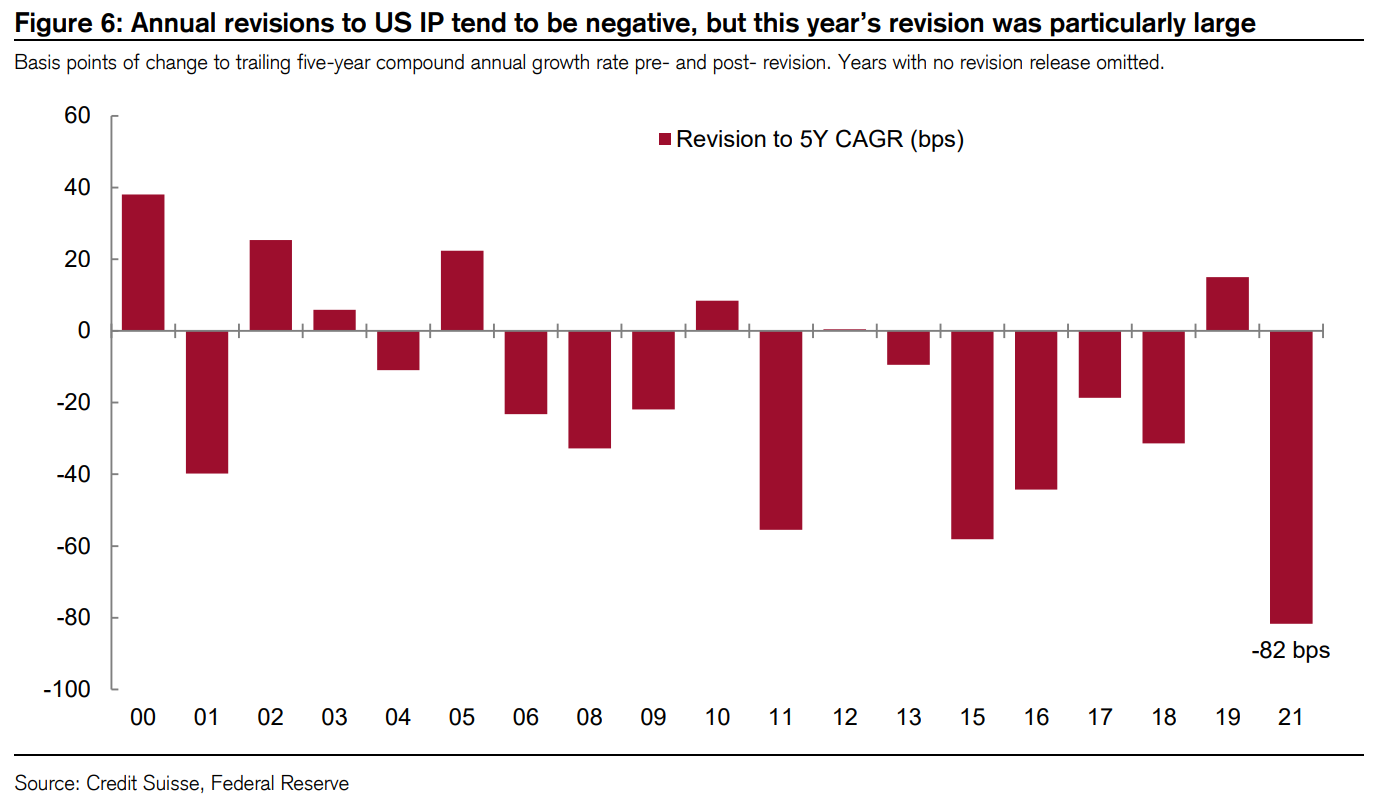

If liquidity growth begins to fall, that implies problems for stocks. For months, the market has splashed in more cash than it knows what to do with. On the model used by Crossborder Capital, that suggests a risk that liquidity leaves too soon. The logic is that if there is a lot of money around, it has to go somewhere. If there are more liquid or safe assets in circulation, it isn't unsafe for a proportion of them to go into stocks. But this theory is vulnerable not only to the numerator increasing (share prices going up), but also to the denominator decreasing, as money supply is reined in. When equity holdings reach prior peaks as a share of world liquid assets, that is cause for concern about share prices, and it happened earlier this month:  We should parse Powell's words, as ever, and those of his congressional inquisitors. But maybe we should be concentrating more on liquidity. Industrial Production (Or the Lack Of It)Revisions to economic data tend to be rather dull, particularly on something like U.S. industrial production which (these days) tends to be regarded as of distinctly secondary importance. So I've only just noticed what's happened following the latest revision. This is how U.S. manufacturing's output has increased since 1946:  To all intents and purposes, the manufacturing sector stopped growing at the turn of the century. It's clambered back from the downturns, but never enough to set new highs. The Nafta trade agreement in 1994 appears to have had no effect at all on what was then steady growth; Chinese accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, however, is a different story. This isn't just ancient history, however. As this chart from Credit Suisse Group AG shows, the latest revision puts a completely new complexion on the last five years. The Trump trade war was previously thought to have left U.S. manufacturing relatively unscathed (unlike, for example, Germany). Nope. Industrial production turned down in 2018 and 2019, the years of the trade tussle:  And while revisions are common, this was a particularly big one. This is from Credit Suisse again:  I'm sorry to point this out late, but the decline in U.S. manufacturing is breathtaking and ongoing. There is no evidence that it was made great again in the last presidential term; and there is an obvious political need for the U.S. to try to do something about this, which will involve intensifying the conflict with China. It's not safe to ignore this. BubblesThis is your reminder that Jeremy Grantham, founder of Boston-based fund management group GMO and for decades a respected market theoretician, will take questions in a live blog on the terminal starting at 10 a.m., New York time. Please send any in advance (which would be very useful), to toplive@blooberg.net. You can also ask questions as the blog unfolds, on TLIV <GO>. Grantham's most contentious position at present is his call from the turn of the year that we are in an old-fashioned stock market bubble: The long, long bull market since 2009 has finally matured into a fully-fledged epic bubble. Featuring extreme overvaluation, explosive price increases, frenzied issuance, and hysterically speculative investor behavior, I believe this event will be recorded as one of the great bubbles of financial history, right along with the South Sea bubble, 1929, and 2000.

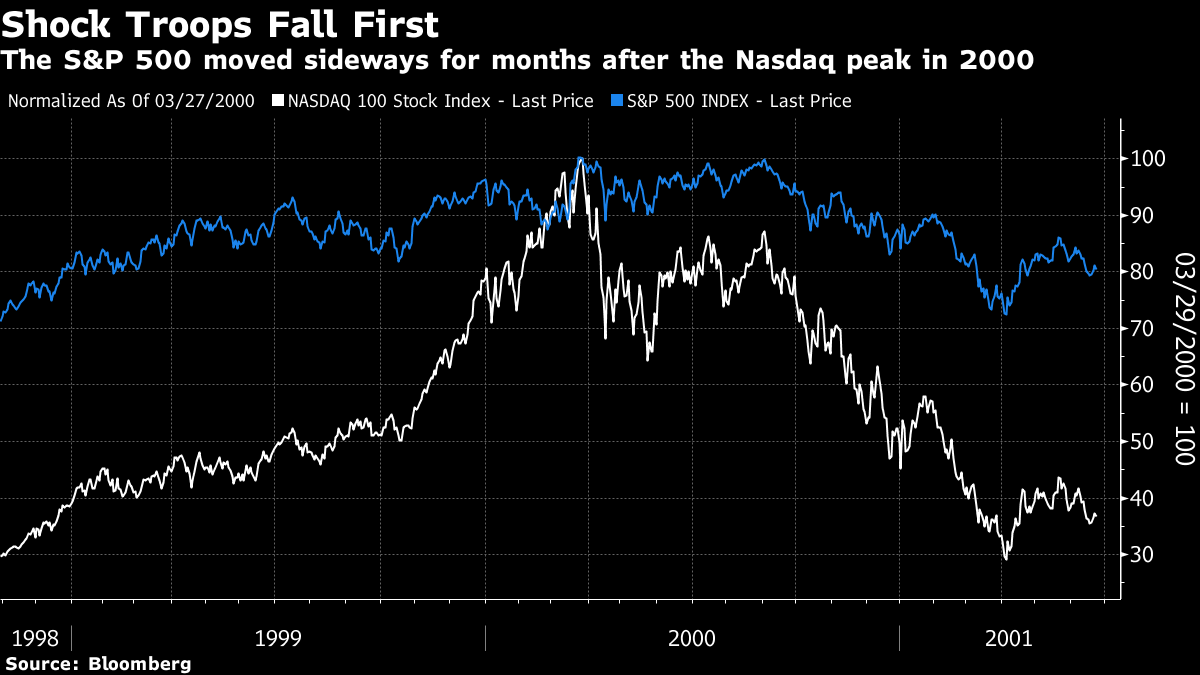

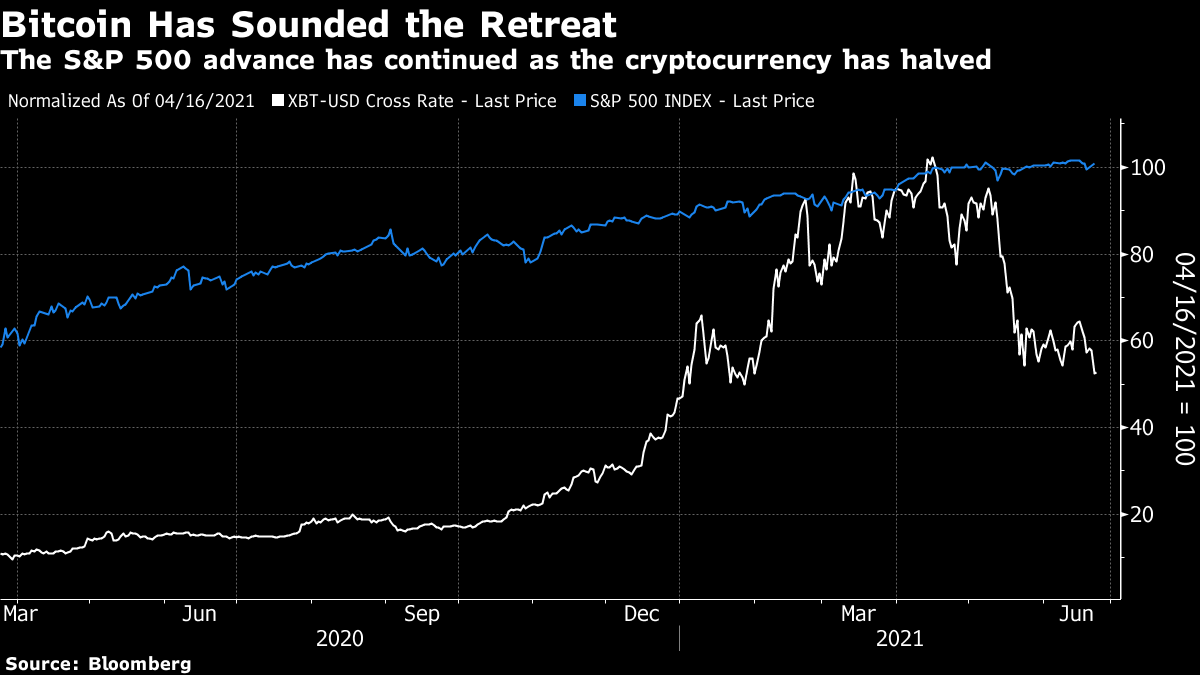

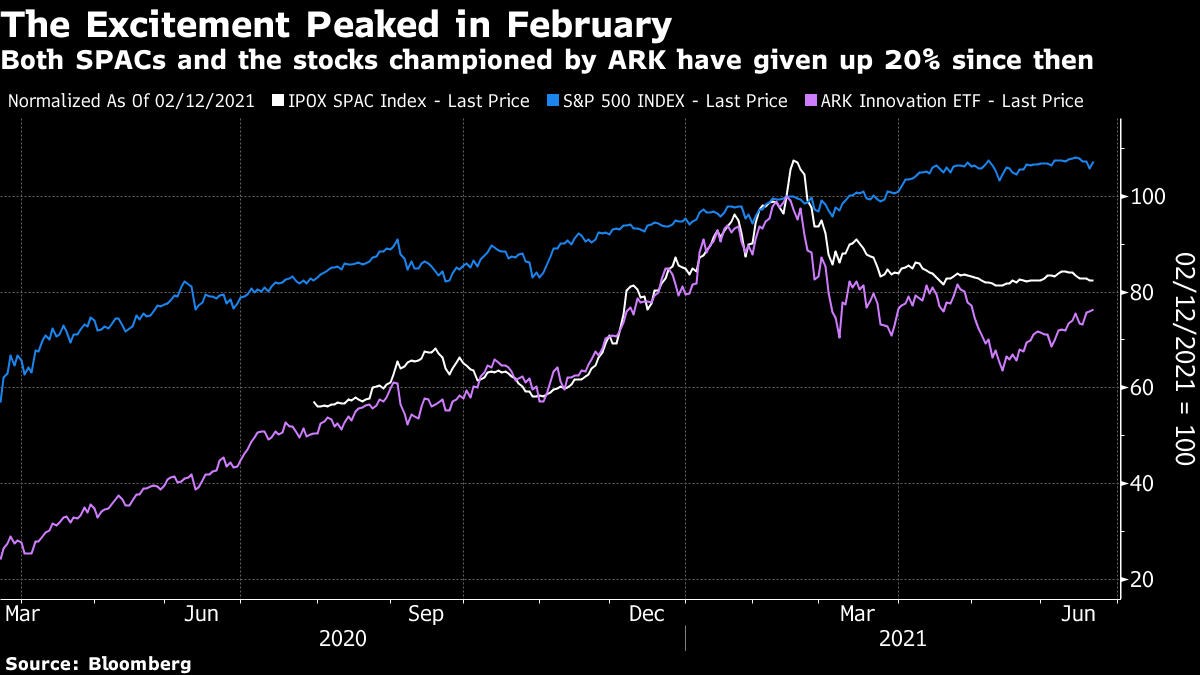

We have plenty to ask about this call. But the most serious issue is whether it's possible to spot the bursting of a bubble in real time. On this, history suggests some worrying parallels. The more exciting investments tend to peak before the less exciting ones. This is what happened to the S&P 500 and the much more exciting Nasdaq-100 at the top of the frenzy in 2000:  Bitcoin has risen more than once already, just as Amazon.com Inc. did after the spectacular implosion of 2000. But if cryptocurrency is the best analogy to the dotcom mania, it suggests risk appetite is in abeyance:  Alternatively, if we take ARK Innovation ETF and the SPAC sector as the apex of stock market excitement this time around, the same exercise yields this 2000-like pattern:  Has this given us fair warning of a 2000 repetition, as Grantham seemed to be warning back in January? Our chance to ask him is at hand. And again, many thanks to him for agreeing to take questions. Survival TipsSport is still wonderful escapism. More or less every non-Russian on the planet was probably rooting for Denmark yesterday after the horrifying events of last week. And, it turns out, Denmark did indeed become the first team to qualify for the knock-out stages of the tournament after losing its first two games, thanks to an emotional 4-1 thrashing of Russia. It was glorious to behold. Now, can England redeem some pride against the Czech Republic after their listless 0-0 draw with Scotland? I had difficulty coming up with great Scottish goals against England last week; when it comes to great Czech goals in the European championship, there are a few to choose from. Karel Poborsky scored this brilliant lob as the Czechs made their way to the final in 1996; and Antonin Panenka scored the most famous penalty of all time as Czechoslovakia won it all in 1976. The Panenka has become a genre of penalty ever since. But remarkably, three of the four semi-finalist nations that year — West Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia — no longer exist. At least the Netherlands is still around. You can see all the goals these four nations scored here. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment