Fads, Bugs, Bubbles and BitcoinRobert Shiller, the Yale University economist who shared the 2013 Nobel prize in economics, is famous above all else for his role in spotting the dot-com bubble before it burst in 2000. The title of the book he published the year before, Irrational Exuberance, has passed into the financial lexicon. And yet he dislikes the concept of a "bubble" and would prefer something else. That was perhaps the most surprising finding when we discussed his latest book, Narrative Economics, on the terminal with him Tuesday. The point of a real bubble is that after it reaches a certain size, all it can do is burst. After that there will be nothing left. There's no chance to release some air and see it deflate gradually, as there might be with a beachball. The word swiftly attached itself to the scandal of the South Sea Bubble in early 18th century England, and its twin the Mississippi Bubble in France. Even Isaac Newton lost his savings before the South Sea Company was revealed to be one big scam. The answer Shiller gave when we asked him if we agreed that the stock market today is in a bubble was surprising: The term bubble, or "boule" in French, appears to have suddenly appeared in 1720 -- it was called the Mississippi event. Speculating on Mississippi became a name for the first really big stock market crash, 75 years before the New York Stock Exchange was founded. Somebody called it "boule" and it has persisted to this day. But it suggests something that is factually wrong, which is that they end in a crash, a one-day event, but that's not historically accurate. So I wish we could have another name for a bubble, maybe call it a fad, fads can come back again in a different form We had a Kewpie doll fad in the 1920s, I think, then we had Beanie Babies, people were buying them thinking they had collectors' value like an investment

I asked if non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, were also a fad rather than a bubble. Yeah, fad is a better term but it's not as unique. People would imagine if we ask them that the 1929 Crash was all over in one day. It fell on Oct. 28 and then came almost all the way up by 1930 and then went down by 1932. But the narrative emphasizes the all-or-nothing crash. We learned it wasn't the case with Bitcoin, it's on its third-wave, like disease epidemics that go in waves.

After a year of watching charts of epidemics in different countries, comparing R-0 rates, cases, vaccinations, excess deaths and all the rest, and applying moving averages to sinister lines snaking across graphs, maybe we should now use our new-found familiarity with epidemiology to give us a new mental model for how markets work, and how they become overpriced. Epidemics are, as we all now understand, an intensely social phenomenon, born of the way in which we interact with each other, and sometimes thwarted by our choices not to interact with each other — just like market manias. As Shiller put it when he was asked about the possibility that exogenous shocks could interact with narratives generated within the market: Epidemiologists speak of "co-epidemics," like AIDS and tuberculosis, which reinforce each other. Epidemiologists also study narratives in some cases at least, in trying to understand the progress of disease. The economy was hurt by some Covid-19 narratives, and the economy affected mitigation efforts that limited the disease. One can, however, seek out mutations, both in the virus and the narratives about it, that seem to be largely exogenous. No one would have predicted that Kanye West would suddenly help the Trump campaign and then switch to run for president! Milton Friedman called such events "quasi-controlled experiments" because they seem unconnected with any economic channel of causation.

Remarkably, the first chapter of the book, published in 2019 before most of us had any reason to have heard of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, is full of the language of epidemics, mutations and contagions. So when I asked if he preferred the concept of an epidemic to a bubble, the reply was clear. Even the Romans, who had a stock market, used epidemic analogies for it: Yes, "epidemic" would be better than "bubble." In Ancient Rome, they referred to "contagio," or contagion. Their word for meme in Latin was "rumor." They were aware of contagion and meme.

So if we are now using the words "epidemic" or "fad" rather than bubble, does that help? Meme stocks at present are a fad, and it's certainly possible to claim that there is an epidemic of enthusiasm in the stock market as money pours in. Both of which speak to the social element of markets. The environmental, social and governance, or ESG, phenomenon is another example of a narrative that has mutated more than once; once known as ethical investing, it morphed into socially responsible investing, or SRI, and then came back as ESG. Much criticized, there is something about the ESG narrative, as with bitcoin, that is genuinely appealing, and that people truly want to believe. Asked if a fad like bitcoin could become an asset class, Shiller pointed out that there is a precedent: It's definitely possible, how did we arrive at the gold standard? Gold is this relatively useless metal, mentioned something like 300 times in the Bible. You can have both long-term and short-term contagions, the contagious idea that gold has value has been going around for thousands of years.

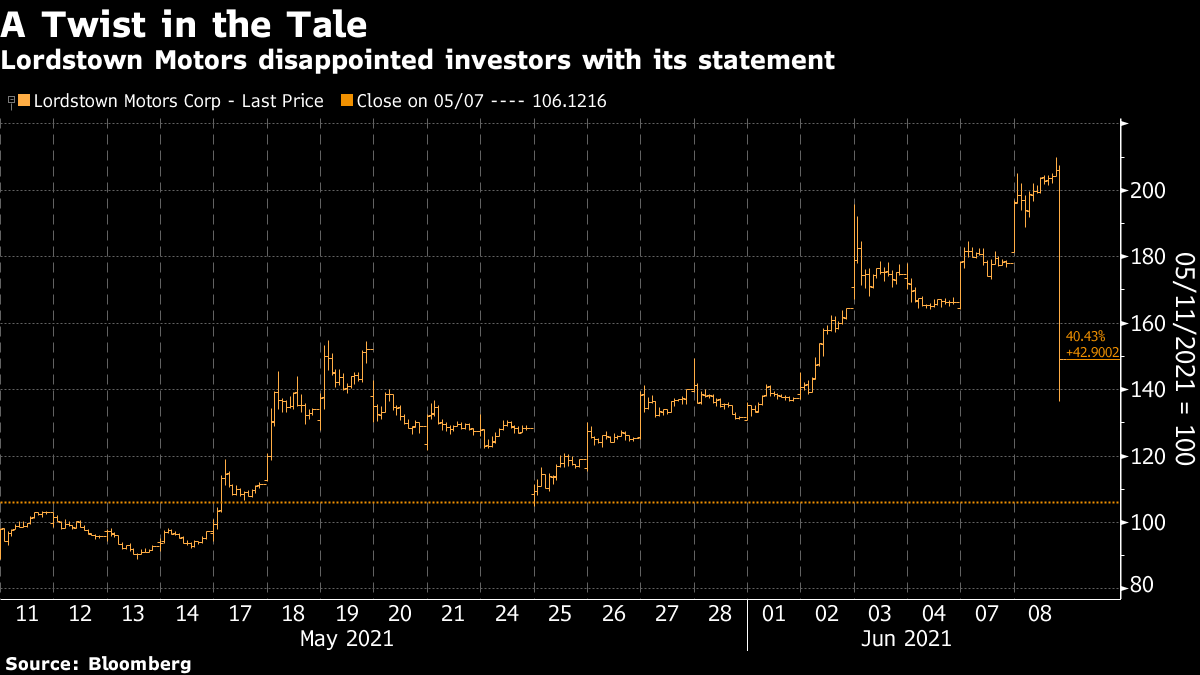

To reiterate, the word "bubble" implies a phenomenon supported by nothing but air that can only burst. That's a fitting description for a Ponzi scheme, or any deliberate fraud. It is also an apt word to capture what the economist Hyman Minsky called the "Ponzi finance" stage of speculative excess, when people are buying into an asset solely because they believe someone will pay them more for it, rather than because they believe in its ultimate worth. Thus many "me too" dot-com stocks behaved just like Ponzi schemes back in 1999 and 2000, even though their backers were honest and sincerely believed they had a business model that would make money. Bitcoin has run into moments of speculative excess that certainly look like bubbles several times already — but as I've pointed out before, the price has gone on to recover. The analogy of a fad, or of a virus that finds a way to mutate, is a better one than a bubble. Many of the most extreme investment manias in history involved the introduction of genuinely exciting new technology, whose valuation was difficult to fix initially. This applies to canals, railroads, and motor cars. There is a burgeoning literature in defending bubbles as a by-product of healthy excitement over investing in new technologies — but it's impossible to support a true "bubble" like the South Sea Bubble or tulipmania. Defending investment fads or epidemics makes far more sense. Our thanks to Shiller for talking to the club, and for tolerating a number of technical difficulties with patience. There should be a transcript available shortly. When Narrative Meets RealityNarratives can create their own reality, but they are still prone to collisions with those based in the cold truth of the real world. That appears to have happened to Lordstown Motors Corp., a startup with plans for an ambitious electric pickup truck. Late in Wednesday trading, Lordstown released a statement saying "the company believes that its current level of cash and cash equivalents are not sufficient" to complete the development of its electric vehicles. This is what happened to its share price in the last 20 trading days:  Even an exciting narrative about electric trucks isn't proof against a statement that a company is about to run out of cash. To quote Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts, who joined us for the discussion with Shiller: To be fair, investors had been warned. Back on May 18th the company filed notified the SEC that it wouldn't get its annual report filed in time due to a restatement of 2020 earnings. I guess some investors don't know how to take a hint. The price charts of AMC, GameStop and Lordstown – not to mention Tesla, ARKK and this week's favorite, Clover Health – all show the same general pattern. A major low in mid-May followed by varying degrees of resurrection. The bulls will argue that a month ago pessimism became extreme and what remains ahead is yet another wave of higher prices… Lordstown could challenge that assumption. Its hard to fantasize about unicorns and rainbows when facts – like the company is running out of cash – get in the way.

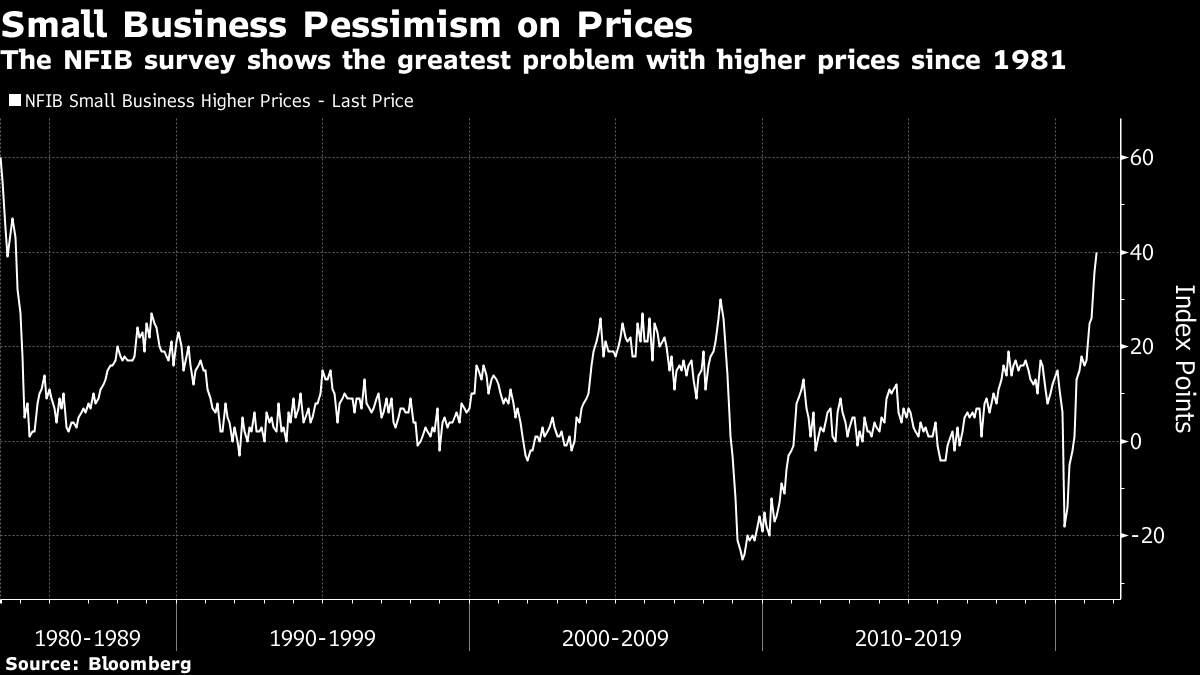

Inflation: Room for DiscussionEarlier this week I took part in a great online debate on inflation, organized by the London-based Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation. You can find it here, and you might it find it interesting if you have an hour to spare.  Leading the discussion was Tim Congdon, a hugely influential economist at a very young age when he helped persuade the government led by Margaret Thatcher of the merits of monetarism, and the wisdom of Milton Friedman. He is still a keeper of the flame for monetarism, which holds that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. It follows that a huge expansion in the supply of money as seen over the last 18 months is very likely to be inflationary, and therefore that Congdon will shortly be proved right. His ideas now seem almost old-fashioned but they are worth following. You can find his detailed forecasts on inflation for the next few years, written with his colleague Juan Castaneda on the website of the Institute of Economic Affairs, and his argument on whether inflation in the U.S will be transitory, persistent or permanent (hint: it won't be transitory) on the website of the Institute of International Monetary Research. The day after you read this, we will get the latest reading on consumer price inflation from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which stands to be the macroeconomic event of the week. To get ready for it, it's worth looking at the latest survey of the National Federation of Independent Business, which found that small business owners are still optimistic, but are troubled by rising prices to the greatest extent since 1981. As the chart shows, at least from their perspective, they are facing by far the most inflationary environment since former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker brought inflation under control in the 1980s.  There is more to inflation than the complaints of small businesses. But the reports of rising prices emanating from all the main business surveys at present are perhaps the strongest evidence that something more than a transitory post-pandemic rebound in prices is under way. The most useful evidence will be available on Thursday morning. Survival TipsReading is always good for the soul. Reading the books we offer for the Bloomberg book club can also be good for your career. Our next offering, which you will have all summer to read, is Winning the Loser's Game by Charles D. Ellis — which means that for the second book in a row, we will feature an author who lives near the Yale University campus in New Haven, Connecticut. Ellis, universally known as Charley, was the founder of Greenwich Associates, chaired the Yale endowment investment committee, and was one of the first to champion the case for indexing. His book, in a new eighth edition, may be the best case for indexing yet made. It should be very interesting, and we plan to have a discussion in September.  And finally, for those who prefer a video to a book, try this: It's a cartoon treatment of the South Sea Bubble, as recommended to me by my son, and it's absolutely brilliant. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment