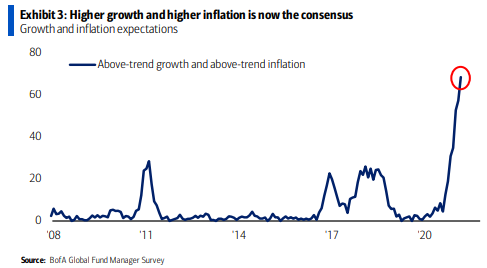

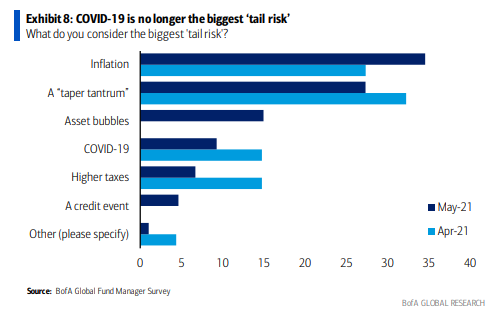

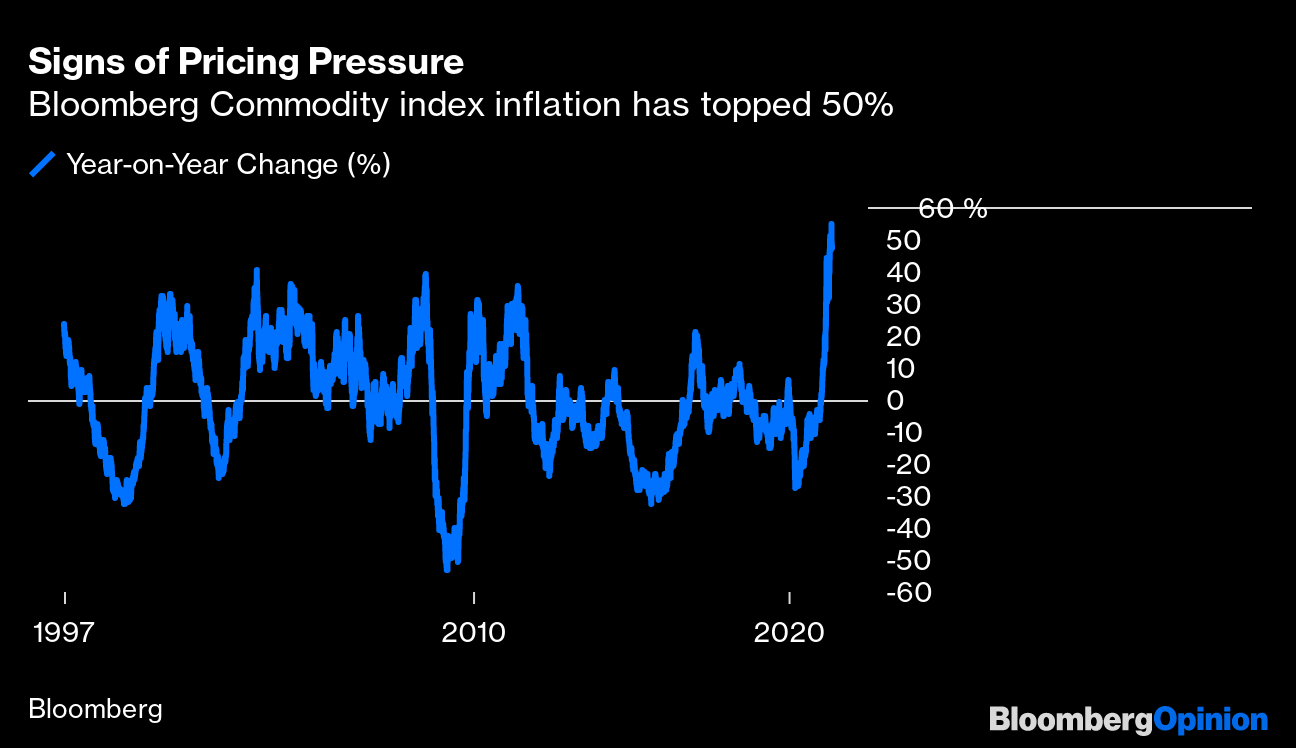

What We Talk About When We Talk About InflationInflation is the topic of the moment. Some cynics can argue that it's only such a big deal because I and other journalists have made it so. But judging by the number of Bloomberg clients who fired in questions for the live blog Q&A session we held on the terminal Tuesday, there is quite a lot of interest out there in the financial markets. And it is the interest in inflation from investors and other consumers of financial journalism that prompts people like me to write more about it; we have the perfect example of reflexivity, in which perceptions can change reality. Beautiful evidence that the current preoccupation with inflation doesn't just come from journalists appears in the latest monthly Fund Managers Survey from BofA Securities Inc. Belief in an inflationary boom is its highest since the survey started:  For the time being, hopes are still pinned on a combination of higher inflation and growth, which is infinitely preferable to stagflation. Rising prices would create new challenges for money managers, but economic expansion would ensure that they aren't insuperable. However, there is an important sign of a shift in perceptions. BofA regularly asks fund managers what they perceive to be the greatest "tail risks." For most of last year, the pandemic was the biggest concern. In March, this had moved on to fear of a taper tantrum. In other words, investors fretted that the Federal Reserve would try to tighten monetary policy too early, and trigger a swift rise in interest rates that brings down the stock market and other risk assets such as emerging market currencies. This is what happened in 2013. Now, however, that has changed. The greatest tail risk is that the Fed moves too late, not too early, and fails to stop inflation from taking hold:  Inflation itself, then, really is beginning to create some concerns. But is there genuine evidence of a clear and present danger? That was one of the first questions asked in the Top Live blog, whose transcript you can find here. Commodity price increases are widely cited as one of the clearest signs of inflationary pressure, but they are also widely dismissed as a symptom of temporary or "transitory" bottlenecks in supply as the economy returns to full strength after the pandemic. Further, there are very low base effects when making comparisons with 12 months ago, which is why the year-on-year rise in Bloomberg's broad commodities index is its highest in many decades:  Jack Farchy, Bloomberg News's energy market correspondent, was on hand to offer some answers. He suggested that it wasn't clear we could attribute all the excitement in commodity prices to transitory factors: it's far from obvious that the rise in commodity prices can be explained away by short-term bottlenecks. Yes, trade flows have been disrupted by things like the Suez Canal closure and the shortage of shipping containers. Yes, some commodity production -- for example, mining in Chile and Peru, and meatpacking in the U.S. -- was affected by outbreaks of Covid last year. But there are also longer-term trends: low investment in new supply by oil companies and miners, amid pressure from shareholders to pay higher dividends and to invest less in fossil fuels. And potential for an extended period of strong demand that has some on Wall Street calling for a new supercycle.

The commodities that have created the most excitement among investors are those tied to the big macro themes. People want to invest in strength in construction (through lumber or steel) and manufacturing (through lithium and cobalt). Industrial metals, such as copper and aluminum have been aided by both effects. Reflexivity, and SustainabilityAnother factor in the commodities boom: reflexivity. Commodities respond to demand and supply, but also to the perception that they are an inflation hedge. Oil futures are often used by traders of Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, to offset risks, so they become directly linked to perceptions of overall inflation. That means commodity prices aren't so much evidence that there really is inflation out there in the real world, as yet more evidence that traders think inflation is coming. To quote Jack: One reason commodity prices have been rising is because investors are ploughing money in as an inflation hedge. If the Fed takes a more hawkish stance, that trade could unwind. Likewise, the Chinese government could try to squash the commodity boom by moving more aggressively to cool the economy.

Beyond that, though, the rise of the electric vehicle does raise the possibility that the materials we most want over the next few years will have to rise in price. The boom in green technologies is great for metals like copper, aluminum, cobalt and lithium, while it also prompts bearishness about oil in the medium-term; although so far that bearishness is mostly expressed in the price of stocks in oil companies, rather than in the price of the commodity itself.  Jack also makes a fascinating point about the most exciting new wave of technology. Tesla Inc.'s idea of a budget, bottom-of-the-range model, the Tesla 3, retails for just under $40,000. A Honda Civic can be had for almost exactly half that. This is that rare example of a technological innovation which, at least initially, is significantly more expensive, and therefore inflationary, than the one it replaces: [F]rom the point of view of inflation, it's interesting because it is, in a sense, inflationary. John made the point earlier about modern iPhones being disinflationary because they've replaced dozens of other devices; well, for electric vehicles it's the opposite story. We can all hope that at some point in the future EVs will be cheaper than combustion-engine cars, but for now they are significantly more expensive. That makes the coming electric vehicle revolution very unusual among technological revolutions: It involves a shift to a higher-cost technology.

PerversityReflexivity doesn't only work through sentiment. Sometimes the technicalities of the market can ease financial conditions just as the fundamentals of the economy suggest that life should be getting more difficult. And no asset benefits more from a perverse desire for safety than Treasury bonds. Bloomberg Opinion's Lisa Abramowicz, who many of you will know from Bloomberg Surveillance, was asked about the possibility of a sharp rise in yields. This isn't surprising; as we have seen, BofA Securities names this as one of the chief tail risks that is currently worrying investors. Lisa pointed out that bad news on inflation doesn't necessarily translate directly into higher bond yields: No one really knows the path this could or would take, because there's also a feedback loop: If riskier assets start selling off, investors typically return to Treasuries, which would put a natural cap on how high benchmark yields could go. And the Fed has shown a willingness to act aggressively when put to the test.

This is very true. There is a well-entrenched, almost Pavlovian instinct for investors to buy Treasuries at the first sign of trouble. This is true even if the source of the trouble is the Treasury market itself. My favorite example of this ultimate perverse reaction came in 2011, when Standard & Poor's began to consider whether the U.S. should keep its AAA credit rating. After the financial crisis and the stimulus applied by the Obama administration, there was ample reason to doubt this. Naturally, a lower credit rating means higher risk of not receiving your interest payments, and should prompt investors to demand a higher yield. The following chart shows what in fact happened to 10-year yields throughout 2011. The three vertical lines show the point in April when S&P said that it was putting the U.S. on CreditWatch, then the date in July when the U.S. was placed on 90-day CreditWatch with a view to a possible downgrade to AA+, and the date in August when that threat was carried out. After all three of these negative events, the Treasury yield fell.  When risk increases, investors dive for the cover of Treasuries — and that is true even if Treasuries are the source of the increasing risk. That could place a limit on the chance of a true tantrum. However, Lisa suggests that it might not work that way again, as investors are tending to jettison the traditional notion of a portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds, on the theory that both could do badly if inflation returns. As she put it: But this time could be different, with some investors abandoning traditional 60-40 investment models in preparation for stock and bond markets selling off in tandem.

It's also not clear that inflation is such a bad thing, given the weight of outstanding debt in the economy. It is arguably the least painful, and also the most politically palatable, way to clamber out from under a huge debt burden. As Lisa put the issue: Which is the more pernicious risk, inflation that's too low or too high? At this point, very high inflation would puncture valuations in a global bond market that exceeds $128 trillion. Relatively stagnant prices would leave companies and countries saddled with record amounts of debt, unable to grow (or inflate) their way out of it.

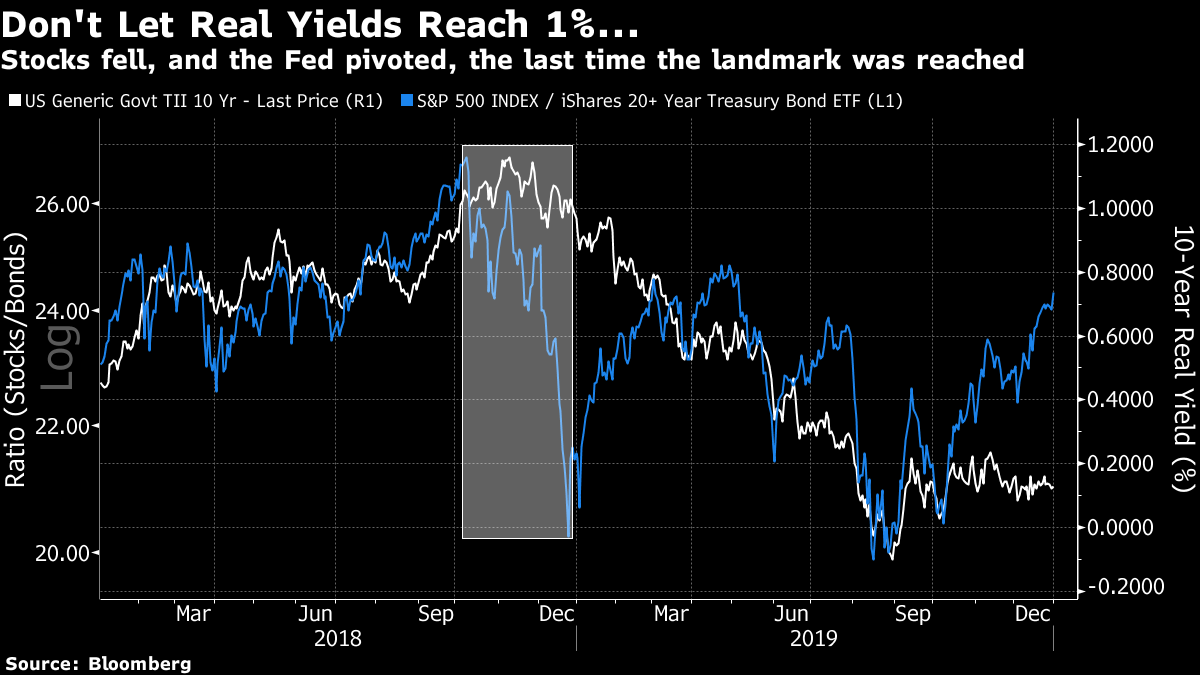

If bond prices were to shoot higher, then there would be a risk of an equity selloff. The rate at which yields rise can be as dangerous as the level they reach. A swift move upward is perilous. If there is a level that is dangerous, then the adventures of Jerome Powell in 2018, his first year as chairman of the Fed, might be instructive. The year began with the Trump corporate tax cut, which was a big shot in the arm for the equity market. For a while, stocks and bond yields rose in tandem. The moment when equities seemed unable to deal with rising bond yields any more came when the real 10-year yield topped 1%, in the first week of October. It spent about three months at that level, during which time, the stock market suffered a severe selloff:  That "Christmas Eve Massacre" was swiftly followed by the "Powell Pivot." The Fed retreated from its intention to trim its balance sheet on "auto-pilot," real yields fell toward negative territory, and once they had got there stocks started to beat bonds once more. As the 10-year real yield now sits at minus 0.9%, there is a way to go before rising yields spark a selloff. Yes, this could happen. Plenty of things could. But it seems to me that the fund managers who told BofA they were now more worried the Fed could leave it too late rather than act too soon were probably right. With plenty of reasonable explanations for why the inflation we have seen so far could prove transitory, it's best to take the Fed at its word and assume that it will keep rates low in an attempt to spark more. The greatest risk at present, it seems to me, is that they succeed not wisely, but too well. I think it's worth reading the entire transcript. These are some of the threads I found most interesting. If you have any ideas for further important questions and topics, please let us know. Survival TipsI was tired and a little sleep-deprived when I entered the local coffee-shop this morning for my regular dose of caffeine. Then they started playing this song, Crazy in Love, Beyonce's first great solo hit (with some help from her then-boyfriend Jay-Z). It's the musical equivalent of a jolt of caffeine, a very flavorful one, perhaps with a subtle sweetener and mixed with an umbrella sticking out of it. Anyway, I had much more energy on leaving the coffee shop than I did when I entered it. Thanks Bey. And as the Bloomberg office received a much-awaited email from HR this afternoon, telling us that we were free not to wear masks in the office if we were fully vaccinated, it almost feels like time to listen to another number from the Queen B's early catalogue. I don't want to tempt fate, but a lot of people are beginning to feel like saying: "I'm a survivor." Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment