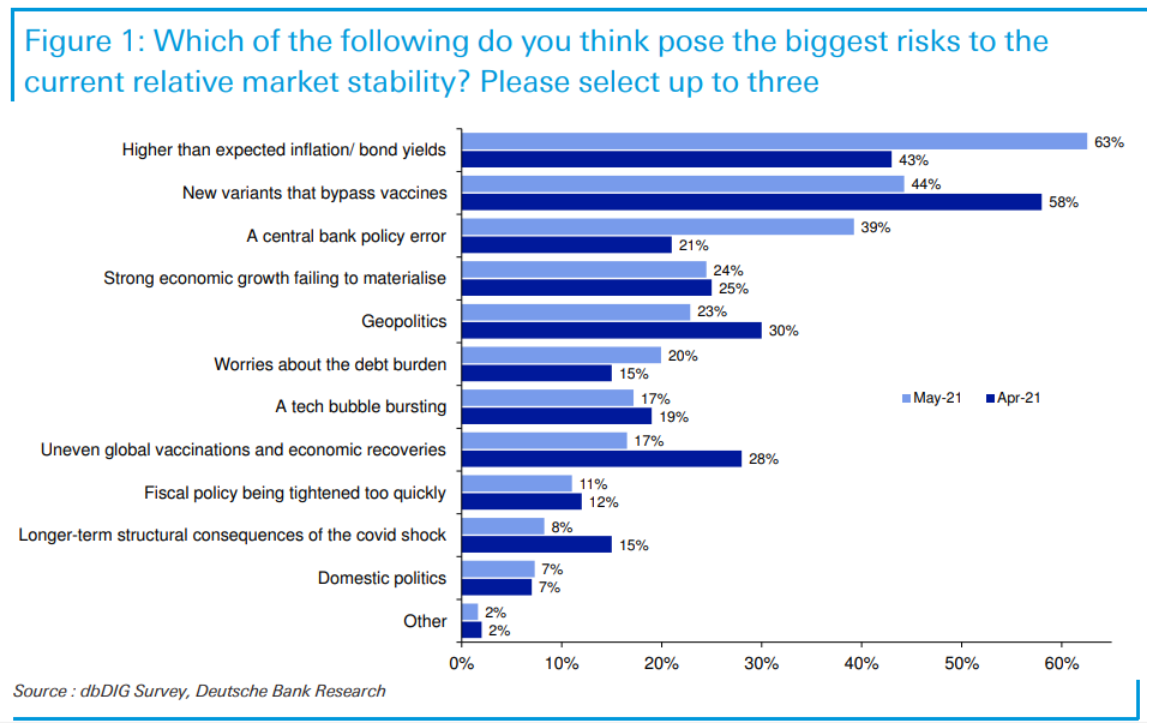

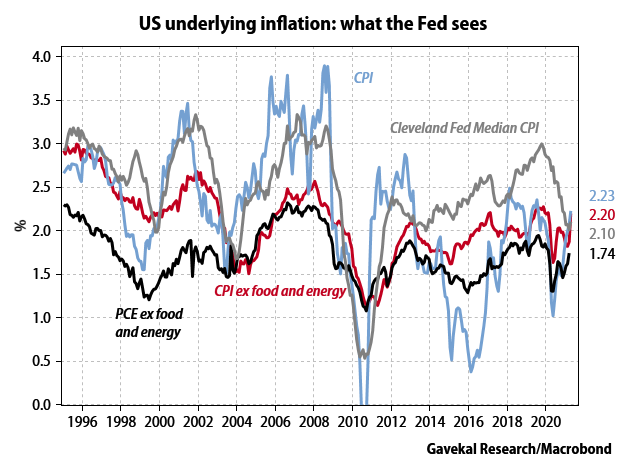

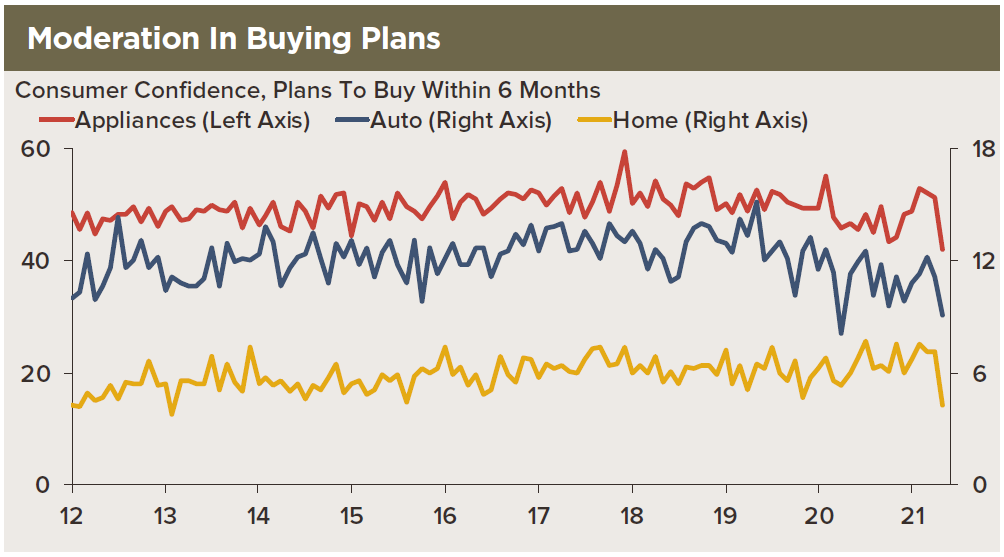

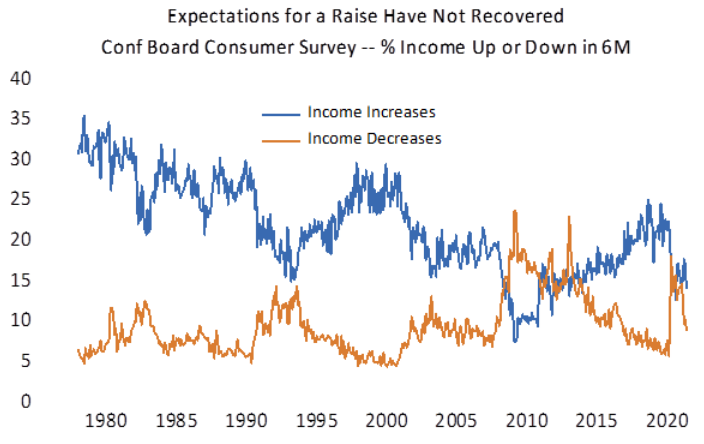

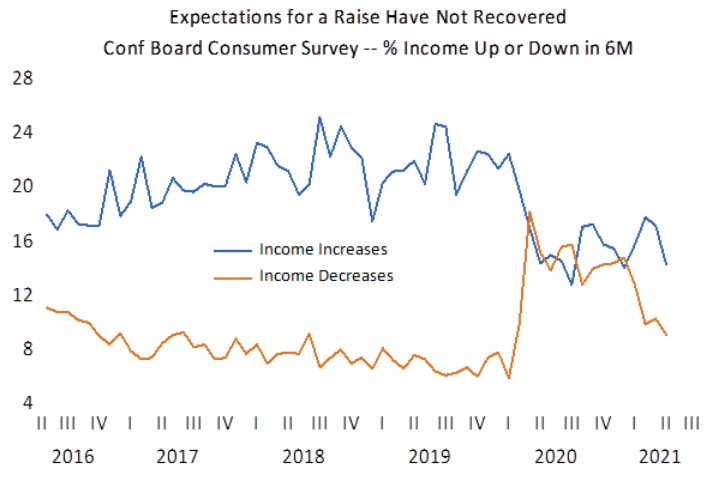

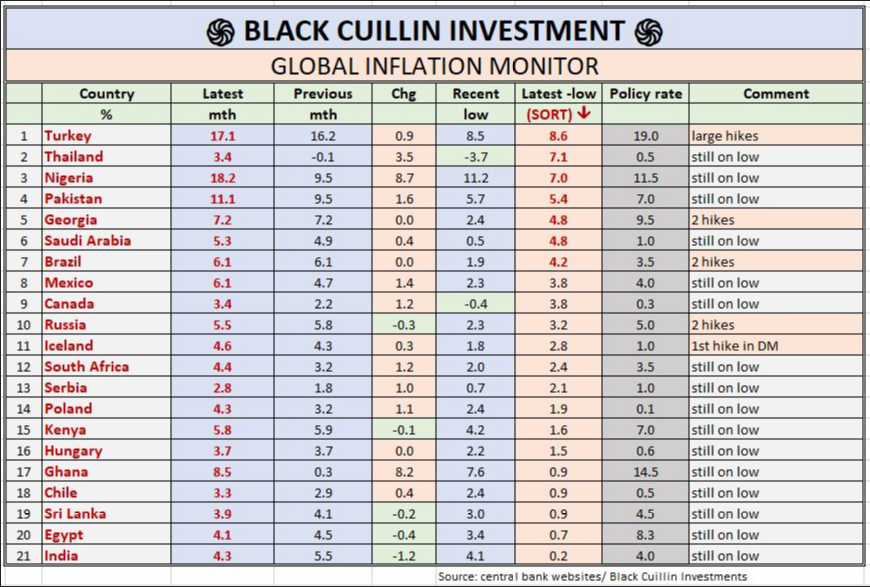

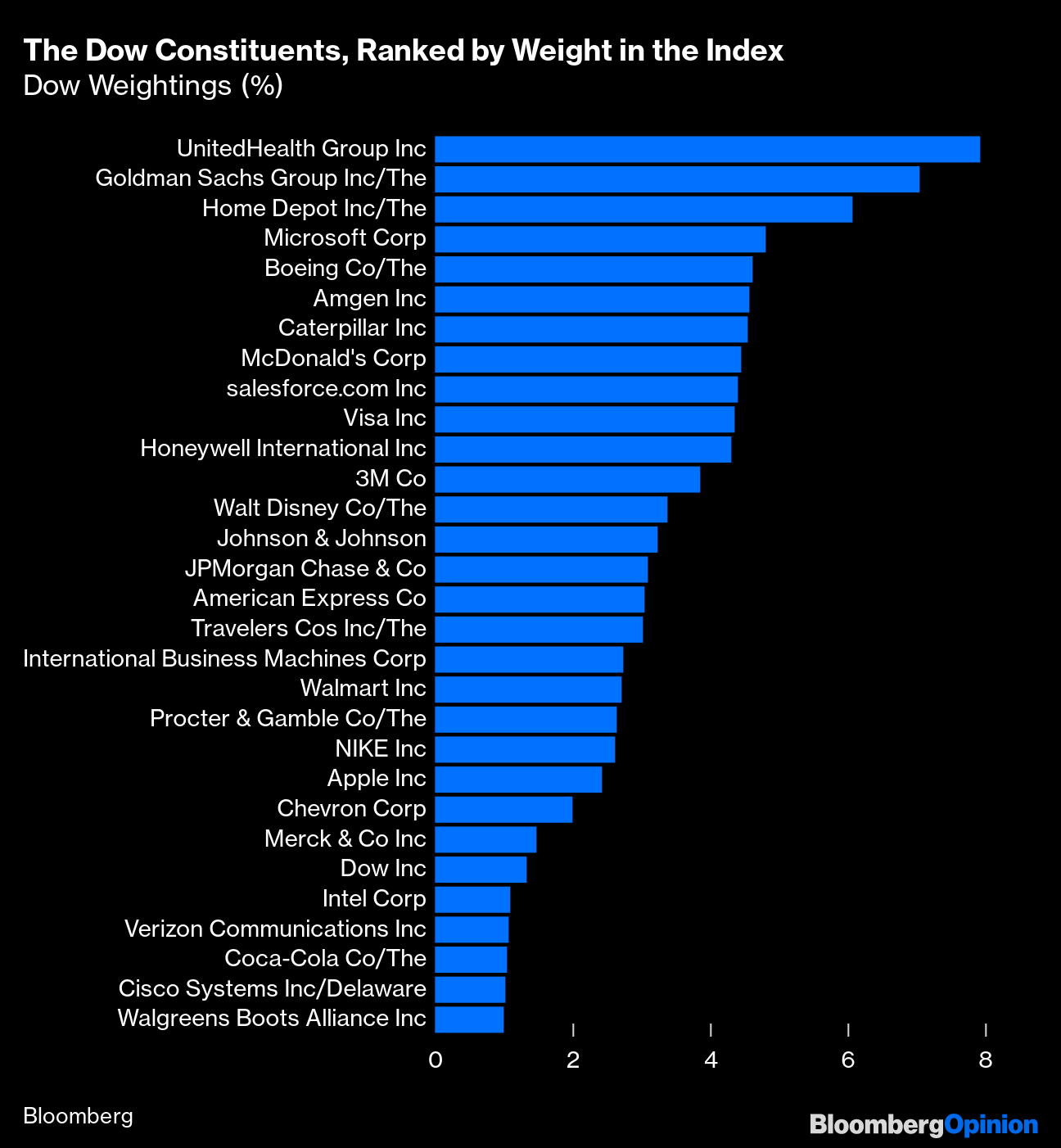

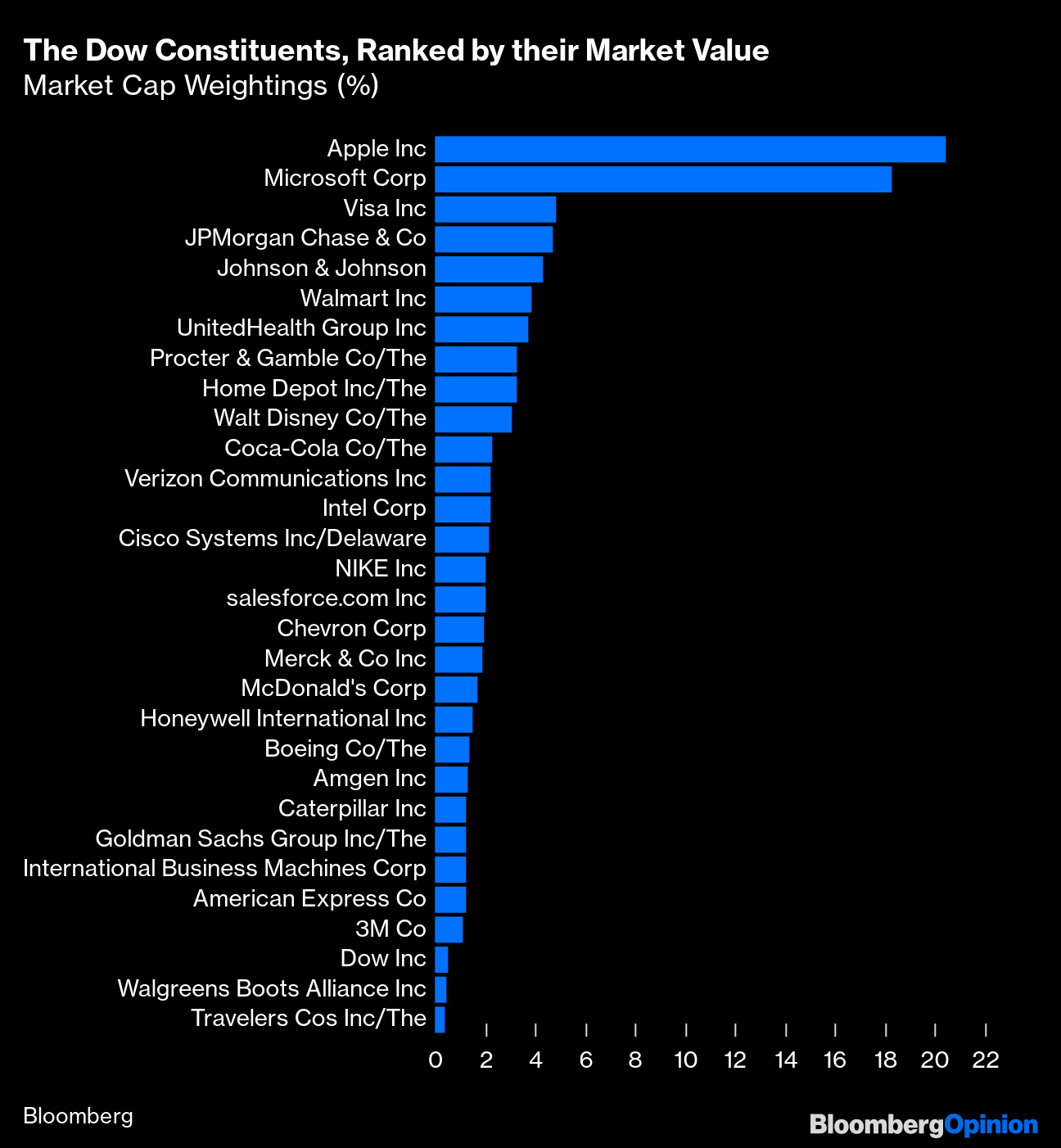

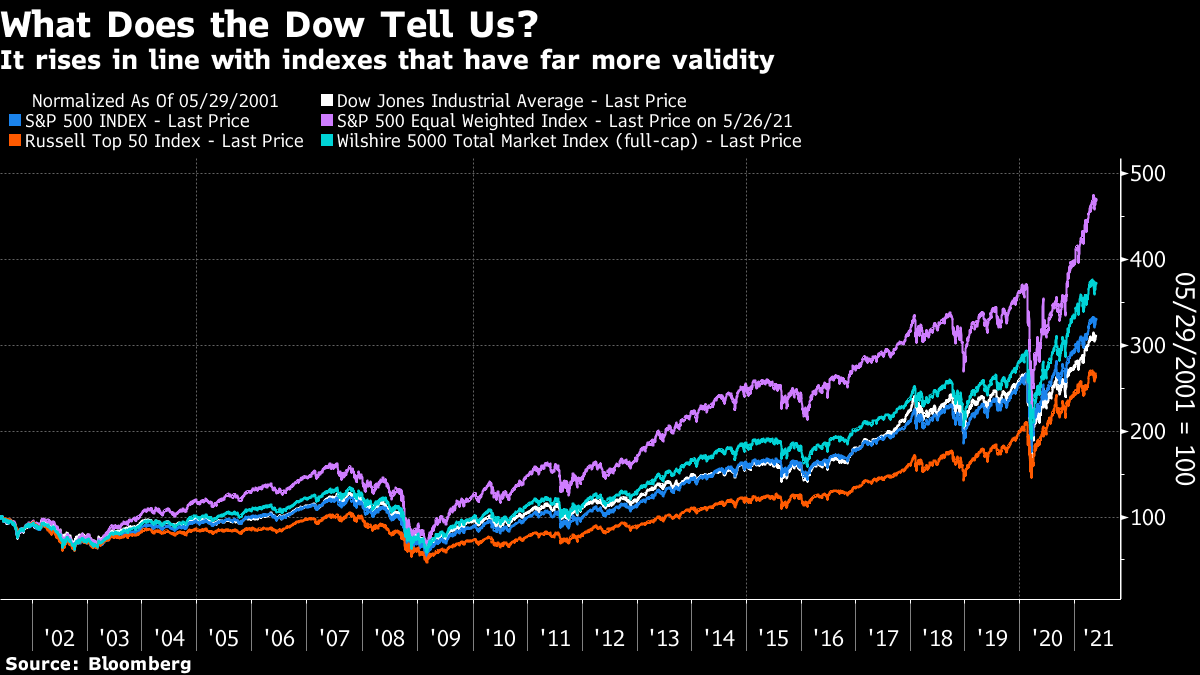

Sunny DazeThis week's market action has been rather dull. For those of us in New York, which has been visited by the year's first wave of soggy, humid heat, this can seem like the beginning of the summer doldrums. Memorial Day weekend, the traditional beginning of the American summer, is at hand. Have people stopped worrying? Or even caring? If, as seems possible, you need a reminder of what we were all fretting about before the heat descended, this is the result of a survey conducted by Deutsche Bank AG's strategist Jim Reid at the beginning of the week. The number-one concern is no longer the possibility of new vaccine-resistant variants of the virus. It's now inflation, and the possibility that it will induce central banks into an error, that plainly monopolizes market attention:  The market torpidity grows easier to explain when we look at what has happened to inflation expectations during the month of May. Following a sharp climb earlier in the year, the yield curve — which is driven in large part by inflation expectations — is no steeper than it was in early March:  Market-based inflation expectations also look calmer than they have done. The Fed's favored 5-year, 5-year breakeven, which effectively measures expected inflation from 2026 to 2031, spiked to 2.4% earlier this month. Since then, it has fallen back closer to 2.2%, the kind of level that the Fed now says (truthfully) it would be happy to tolerate:  This isn't unalloyed good news. If markets don't expect so much inflation, it implies that they also don't expect so much growth. But after the stock market rushed in short order to historically extreme valuations, this kind of not-too-hot-not-too cold "Goldilocks" outlook is just what investors needed. It's also just what the Fed wants to see. Are we right to be calming down about inflation after the shockingly high CPI print earlier this month? The following chart from Anatole Kaletsky of Gavekal Research suggests there is little reason for great concern just yet. It shows four separate popular readings of U.S. inflation, in all cases using the average over the preceding two years, rather than the previous 12 months. This flattens out the epic collapse in activity last year and the subsequent scary acceleration to produce underlying inflation numbers that the Fed will think (according to Kaletsky) look comfortably under control. They might even encourage the Fed to keep the pedal pressed to the metal to try to spark some life into the labor market:  Another reason for relaxation is that the Fed has said, repeatedly, that it now cares about outcomes rather than forecasts. The actual data need to worsen before it moves. Assuming we can trust Kaletsky's argument that they are looking at two-year inflation rates, there is no data as yet to suggest an urgent need for the Fed to start tightening. This week's numbers have if anything provided further reassurance. This has been second-tier survey data, but it all contributes evidence. The Conference Board's survey of consumer confidence provided a number of clues that inflationary pressure isn't too great. First, illustrated by a graph from High Frequency Economics, is that consumers' plans to buy a range of items within the next six months have actually fallen somewhat. People expecting inflation are more likely to bring purchases forward to avoid higher prices, so this suggests reducing inflationary pressure:  From the same survey, Steve Blitz of TS Lombard points out that expectations for a rise in income over the next six months remain low by the standards of the last decade:  If we look at the data in closer detail we can see that the number braced for a pay cut shot up during the pandemic, and is now returning to normal, But the number expecting a raise is no higher than it was during 2020's worst months. There is no sign here of an incipient wage-price cycle, and therefore, logically, little reason to be alarmed as yet by any possible pickup in structural inflation:  All of this is a U.S.-centric view. Japan and the euro zone, dogged by lowflation for years, are unlikely to succumb to inflation before the U.S. does. There might be more reason for concern about emerging markets, however. The following chart, from Stephen Mitchell of Black Cuillin Investment in London, shows the latest inflation levels for a range of countries, ranked by the amount by which it has risen above its recent low. Several with inflation sharply above the low haven't yet started to hike interest rates. On this very simple basis, the places to look for nascent inflation psychology are in the emerging world:  If there is an imminent inflationary danger anywhere on the horizon, it is that commodity prices and the gusher of money from the U.S. help to tip a number of emerging countries into crisis. That moment hasn't arrived yet. For now, it appears, everyone can relax. That, at least, is what they are doing. Wednesday marked the 125th birthday of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. That's a fine old age. Now it's time for the Dow to retire. I feel a little like Don Quixote tilting at windmills when I tell people to ignore the index. Revolutionary for its time, it provided a measure of the broad market and not just individual stocks, and was part of the rise of the Wall Street Journal to its place as the chronicle of American business. The Great Crash of 1929 was all counted out, in real time, in terms of Dow Jones points. The Dow's historical importance is undeniable. But the same can be said of more recent innovations, such as the Model-T Ford or the fax machine. Nobody would deny that they were important for their time; that doesn't mean you would use these technologies today. The Dow has evidently been superseded. It is a list of 30 stocks, chosen at the discretion of a small committee. At one point, membership was limited to industrials; to be included was a badge of honor, and turnover was deliberately kept low. As time went by, turnover has increased, and its membership now includes tech companies, pharmaceutical groups and banks. The great fall of General Electric Co. means that no original member is still in the index. It is no longer clear what the Dow is supposed to represent; it's no longer just industrials, and it isn't a list of mega-cap companies. Constituents vary in size from more than $2 trillion (Apple Inc.) to $39 billion (Travelers Cos.). Recent inclusions seem to have been driven by a desire to reverse engineer the index to keep it moving as closely in line with the S&P 500 as possible. But the real problem with the Dow is its methodology. It started as a straight average of the share prices of the member companies. In the days when the whole thing had to be calculated by slide rule, this was defensible. These days, less so. The result is that companies can be wildly over-or under-represented according to whether they happen to have a high dollar share price. This soon lapses into absurdity. Here are the current Dow stocks, ranked by their percentage weighting:  UnitedHealth Group Inc. has more than double the weighting of the world's most valuable company, Apple. Here is that same list, ranked by market cap:  Note that a) weighting the Dow the present way is indefensible, and that b) if this group of companies were weighted by market cap, nobody would be interested as more than 40% of the index would come from two tech companies. Does this distort things? It does a bit. Much is made of the fact that the Dow correlates closely with the S&P 500 over time — although this tends to concede that the S&P 500, which is market cap-weighted, has greater validity. But it travels a ludicrously circuitous route to get there. The combined market cap of the companies in the Dow has risen by 5.62% so far this year. But Goldman Sachs Group Inc. is up 37%, and it accounts for more than 7% of the index. Thanks to the overweighting of Goldman, and a few other absurdities, the Dow itself is up 12.14% for the year. That's more than double the increase in the value of its constituent companies and remarkably is very similar to the 11.71% gain in the S&P 500. I fail to see how the coincidental similarity of these numbers justifies using an antiquated method for weighting the companies. Despite all of this, does the Dow add something to our understanding of the U.S. stock market? If it does, I fail to see what it is. The following chart compares the Dow to the Wilshire 5,000 index (the closest U.S. approach to an "all-share" index) and the S&P 500 on a cap- and equal-weighted basis, and the Russell Top 50 index, which is restricted only to the biggest 50 companies. This is how they have fared over the last two decades:  All are obviously closely correlated with each other. The Dow does better than the Top 50, and worse than all the others. It seldom moves in a different direction from them; but if it did so, it would be sending a misleading signal. It is literally of no use to anyone, and there is no reason why anybody should take any interest in it. It's possible to argue that it's harmless to keep feeding people with the index to which they have grown accustomed, but that is a counsel of intellectual dishonesty. It's not a rigorous measure of the market, and shouldn't be presented as such. Nobody in the financial world cares about it; the only reason people outside the financial world do is because it continues to be presented to them as the best single measure of the market. For a really simple fix, how about the following? Take the S&P 500, by far the world's most tracked index, and change its name to the Dow Jones 500, or "the Dow" for short. Then quote it. If necessary, multiply the headline number of the S&P so that it starts with the same number of points that the Dow had. Both indexes belong to the same company these days. That way, financial media can continue to report "the Dow" as though nothing has changed, but they will be giving the investing public some information that might actually help them. Just a suggestion. Survival TipsNormality is fast approaching. We now have an opening date when In the Heights, a homage of praise to my local neighborhood of Washington Heights , will be on show in cinemas. Lin Manuel Miranda has a happy knack of making his home barrio look wonderful. The streets aren't totally full of music, as he says, and our enormous local open-air swimming pool (site of formation synchronized swimming in the movie) was forced into serving as a Covid testing site last summer. The movie will be worth seeing, and it's premiering on June 9, just around the corner in the gilt-and-stucco splendor of the United Palace. Then you'll be able to stream it. Look it up, and let's hope the world doesn't need to close down yet again after this reopening. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment