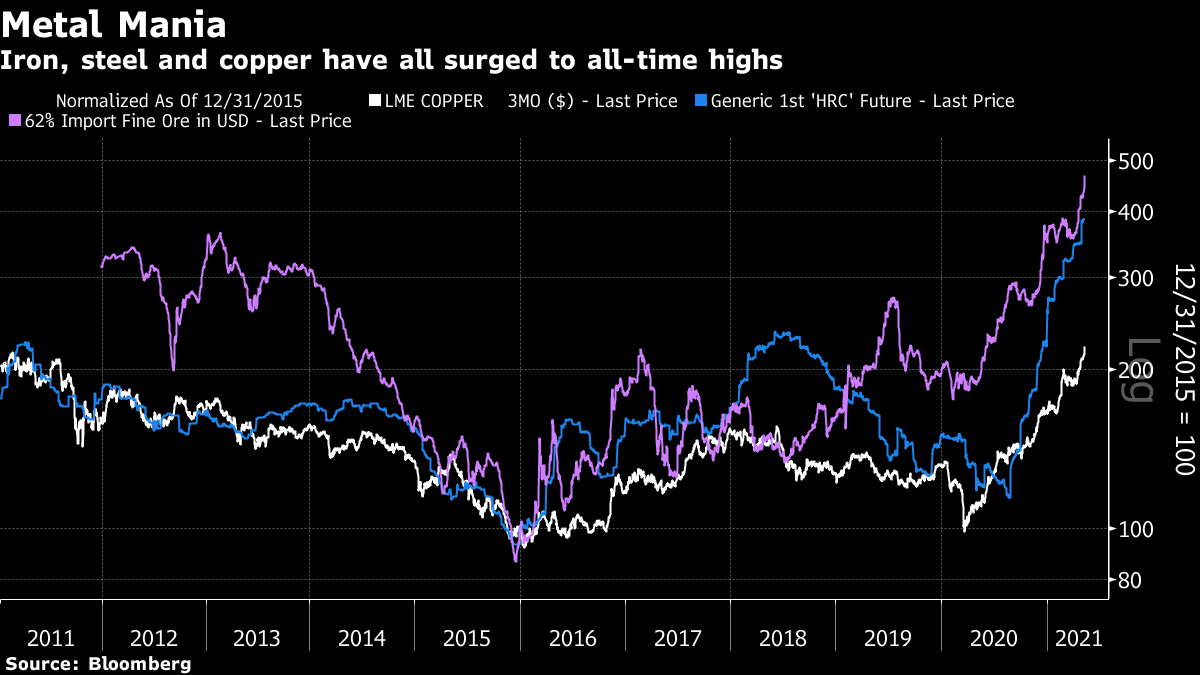

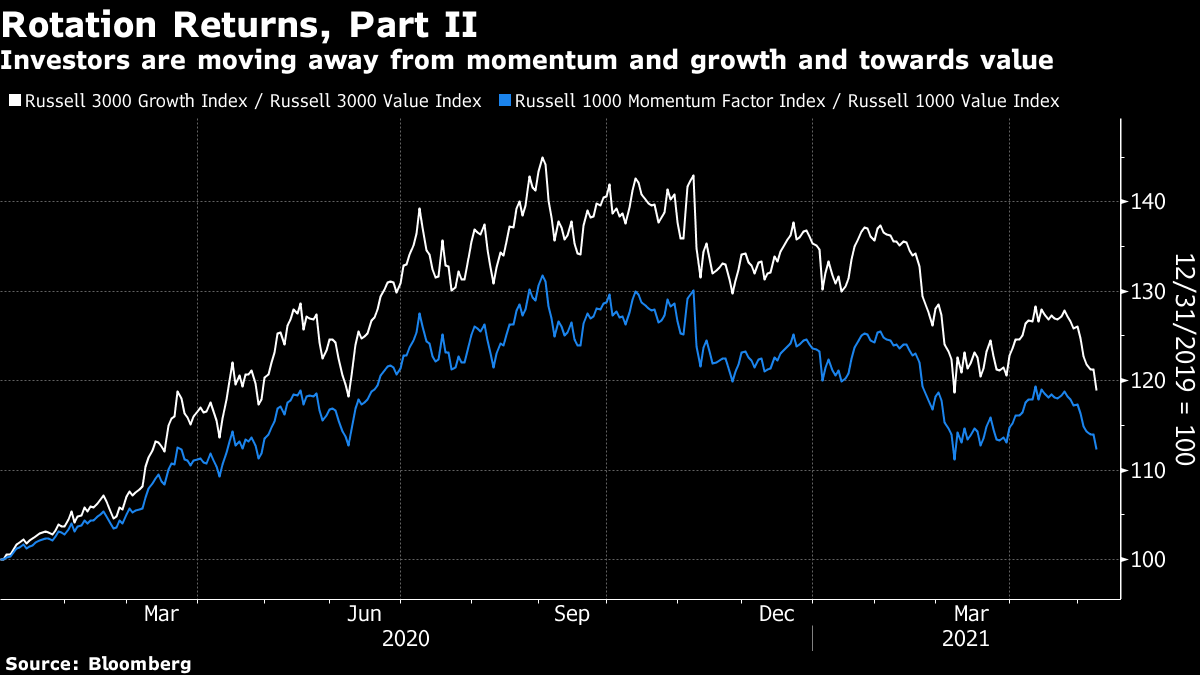

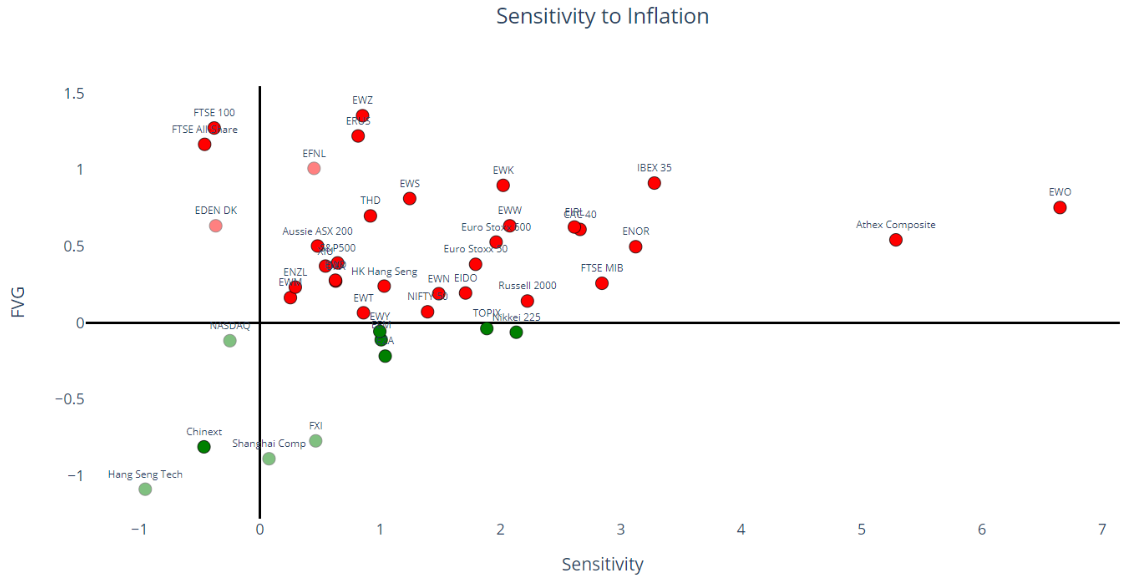

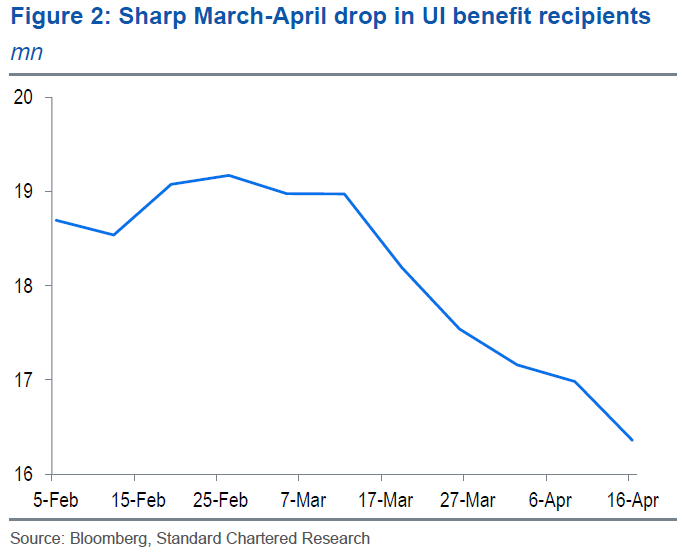

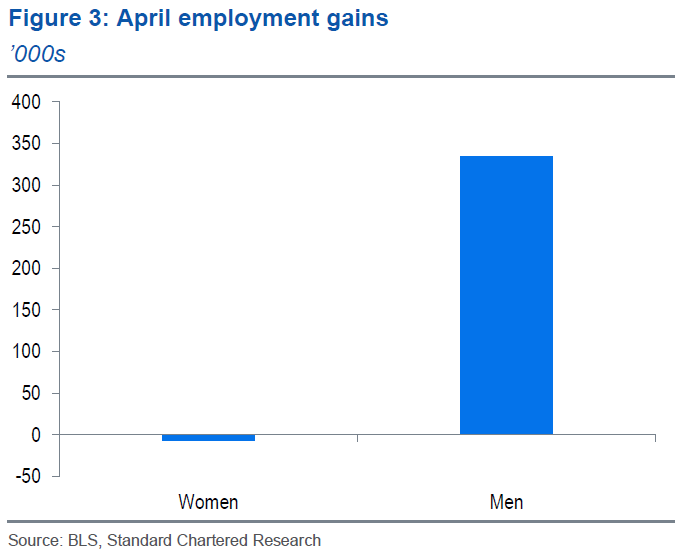

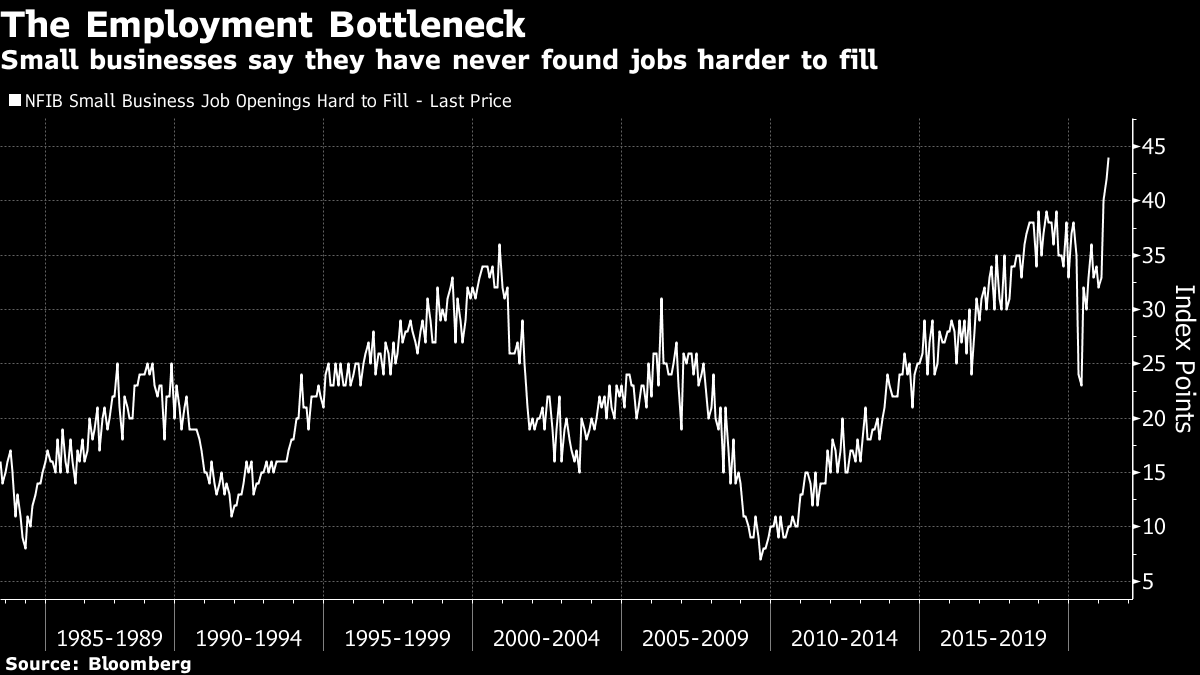

Thud.Friday's U.S. unemployment data, which were far, far worse than had been expected, are still having an impact. Their effect was like that slapstick comedy moment when a clown holding a plank turns and inadvertently whacks his friend on the side of the head. Just as the "straight man" gets back on his feet, the clown turns again and whacks him on the other side. In this case, the first thump came with the data, the second with market reaction that in some ways was almost the opposite of what might have been expected. Core financial conditions behaved the way they were supposed to. Real yields, arguably the ultimate sign of easy monetary conditions, dropped back again and are now once more below the trough reached before the "taper tantrum" of 2013, which was the historic low until Covid. Real yields had risen as investors positioned for a robust post-pandemic recovery, and many braced for a repeat of the sharp increase seen during the tantrum. Such an event has at least been postponed:  Meanwhile, broad gauges of financial conditions, which include measures of liquidity, short- and long-term yields, and valuations on equities, are now the easiest they have ever been. On this, Bloomberg's financial conditions index is in agreement with Goldman Sachs Group Inc.:  In these crucial respects, the market reaction has been just as might be expected after very disappointing economic data — people adjust their forecasts, and position themselves for easy monetary policy long into the future. As a result, financing gets easier to obtain. CommoditiesReaction in the market for raw materials, however, has been almost the exact opposite of what you might anticipate. Prices of the main industrial metals had been rising impressively for months, and reacted to the jobs miss by heading for the moon. The following chart shows the prices of copper (at a record high) as well as the most widely quoted benchmarks for steel in the U.S. and iron ore in China. All are rebased to the beginning of 2016, which marked the bottom of the brief deflation scare driven by the botched Chinese devaluation of 2015:  Other commodities didn't join the party, with the energy market dominated by fallout from the Colonial Pipeline shutdown. But Bloomberg's overall commodity index remains at a level not seen since July 2015. Metals prices like this would normally imply strong certainty about global reflation. EquitiesThe reaction in the stock market has been counterintuitive. The S&P 500 set a fresh all-time record Friday, which was a reasonable response to easing financial conditions (though not to signs that the economy wasn't rebounding on cue). The big surprise for equities of late has been a positive one, with what looks like a historic earnings beat during the first quarter. But Monday has confirmed a deeper reaction: the rotation away from the safe names that dominated during the pandemic's most frightening months. This started in full force on Nov. 9, now largely known in markets as Vaccine Monday, when Pfizer Inc. published its spectacularly successful trial results. The rotation toward more cyclical names that should benefit from reflation was checked for a while, in line with the pause in the bond market, as inflation breakevens stopped rising. Now it is on again. That was visible most spectacularly in the Nasdaq Composite index, which dropped 2.55% for its worst day since March. It was a particularly awful day for the mega-cap FANGs, with the NYSE Fang+ index falling more than 10% below its peak last month. The NYSE Fang+ index is now its lowest compared to the equal-weighted S&P 500 index since July last year. Another version of this rotation has been even more extreme, with the S&P 500 information technology sub-index at its lowest relative to the KBW index of big banks since early March last year, before Covid had done its worst:  This strong rotation shows up just as clearly if we look at equity factors. Using the Russell indexes, we find that both the momentum factor (the tendency for winning stocks to keep winning while losers keep losing) and the growth factor (choosing stocks with the most reliably growing earnings) are at fresh post-Covid lows relative to value (buying stocks that look cheap relative to their fundamentals):  This is consistent with increased expectations of growth, which seems odd immediately after a savagely disappointing unemployment report. When growth is abundant, there is less need to pay up for the stocks that offer it, while cheap companies become more scarce. Judging by the falls for some of the FANGs that have logged impressive gains over the last year, this is a pure rotation in which investors sold some stocks in order to buy others. Even if there is a rotation away from the previous leaders, U.S. stocks as a whole remain close to their records. This is because for the time being, more inflation is good news. Investors want more growth, and don't mind if that comes with some inflation. And this is a global phenomenon. The following chart from Quant Insight Ltd. of the U.K. maps exchange-traded funds covering different global markets with their expensiveness (according to QI's metric) on the vertical scale, and their sensitivity to more inflation on the horizontal. The further right, the more a market is positively affected by a rise in inflation. Markets below the line are cheap. Most importantly, markets to the left of the vertical axis are now negatively affected by inflation. The critical point comes when markets begin to move from the right to the left of the vertical axis. When this happens, inflation has started to become bad news. On this basis, the U.K. is the only major market that looks expensive and where any more inflation would create problems. The country tends to have higher inflation than the rest of Europe, so this makes sense. The same is true to a lesser extent of some Asian technology markets, although QI says they aren't in a clearly defined macro regime:  Countries on the periphery of Europe, including Spain, Greece and Italy, and also Austria, are still in a position where more inflation would be fantastic. Other big markets remain positively affected. So, a variety of assets, from bonds through commodities to stocks, have responded to the unemployment data as though it is inflationary. Is it? So, Is a Bad Jobs Number Inflationary?Economic orthodoxy going back a long way holds that employment and inflation should broadly follow the Phillips curve relationship, which in brutally over-simplified terms posits that higher inflation will mean lower unemployment, and higher unemployment will mean lower inflation. How then did higher than expected unemployment prompt people to place more bets on higher inflation? There are various theories for how everyone got this number so wrong, and some of them imply that this is the "wrong" kind of unemployment for lower inflation. One popular and logical explanation canvassed on Friday was to blame the disincentives that come with generous unemployment benefits from the Biden administration. If the disadvantages of unemployment are reduced, then the case for finding a job gets weaker. This could be an interesting test case for labor economists to examine over the years to come. But at least one crumb of evidence suggests that this wasn't a decisive factor. Steven Englander of Standard Chartered Plc shows that from March to April there was a sharp drop in the number of unemployment insurance benefit recipients. At first blush, we wouldn't expect this if benefits were deterring people from work:  Englander offers a snippet of evidence to support another theory, which is that the continuing complete or partial shutdown of schools in many parts of the country, and the difficulty in finding childcare, is depressing the number of people looking for work. Men are just as capable of staying home to care for children, but the fact remains that the burden tends to fall far more on women. And the gender disparity in last month's figures, with a big gain in male unemployment while the number of women in a job fell slightly, suggests that this theory has something to it:  If this is true, and it doubtless contains an element of truth, then the bad April number reflects an artificially limited supply that should be transitory — although with the summer vacation approaching, it could last at least until September. While this continues, the market will behave as though it is tighter than it otherwise would be. In other words, there will be greater upward pressure on wages, and more inflationary pressure, than normal with employment at this level. The most concerning theory to explain what is happening is that there is a skills mismatch. There aren't enough people with the skills that employers want. That means they have difficulty finding good people, while anyone who is well qualified will feel emboldened to ask for more. That implies something stagflationary; wage inflation kicking in before employment has fully recovered. Exhibit a) is the data series on "quits" — people leaving voluntarily — which staged an almost instantaneous rebound last year. Data take a while to compile, but the February figure suggested that about as many people were taking the risk of quitting as ever do. That in turn implies that this is more of an employees' market, which would mean wage pressure:  Small businesses in particular seem to have a problem lining up appropriate people. The next report from the U.S. National Federal of Independent Business, a lobby group for smaller companies, is due Tuesday. The survey includes a question on whether members are finding it hard to fill vacancies, and the last reading was the highest in the four decades that it has asked the question:  If that number increases further, it will add to the notion that the economy is suffering from serious skill mismatches. And that would make people more confident to bet on inflation. Friday's whack around the head from the unemployment report has just sharply increased the importance of that NFIB survey. And then Wednesday will bring the official CPI data themselves. There could be plenty more opportunities for clownish activities with a plank. Survival TipsNews that the Pfizer vaccine has been approved for children as young as 12 in the U.S heightens the sense in this country that the pandemic is well on its way to being only an irritant in our lives, and no longer the governing force that it has been for the last 15 months. There was also something like a party when I arrived at the Bloomberg head office this morning and discovered there was a line around the block for the Covid test we must all have at least once a week if we are to enter the building. Most people, myself included, seemed happy about this. We might have to hang around on the sidewalk for 10 minutes, but there was still something wonderful about this affirmation that we were all here to tell the tale, and that life was returning to normal. We may be fast approaching normal, but of course we aren't there yet if it's necessary to have a nurse in full PPE take a swab from your nose once a week. And there's a horrible sense that this disease, like other epidemics before it, is about to morph from an intense developed world problem into a plague on the emerging world. But even though the pandemic isn't over, the first rash of truly good analysis of how this was allowed to happen is beginning to appear. Let me recommend three podcasts. First, try the mighty Michael Lewis, writer of Liar's Poker, Moneyball and many other modern classics, talking about his new book The Premonition. Amazingly, Lewis has found the ideal character through whom to tell the story of how the pandemic might have been thwarted — a young public health official who, like the hedge fund managers in The Big Short, could see the crisis coming. Lewis reads from the book and interviews himself on his own podcast, and talks about it on the New York Times Book Review podcast. For another moving take on the responsibility we all bear to each other during a pandemic, try the latest episode of Cautionary Tales by my former colleague Tim Harford, on the tragic story of the movie star Gene Tierney. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment