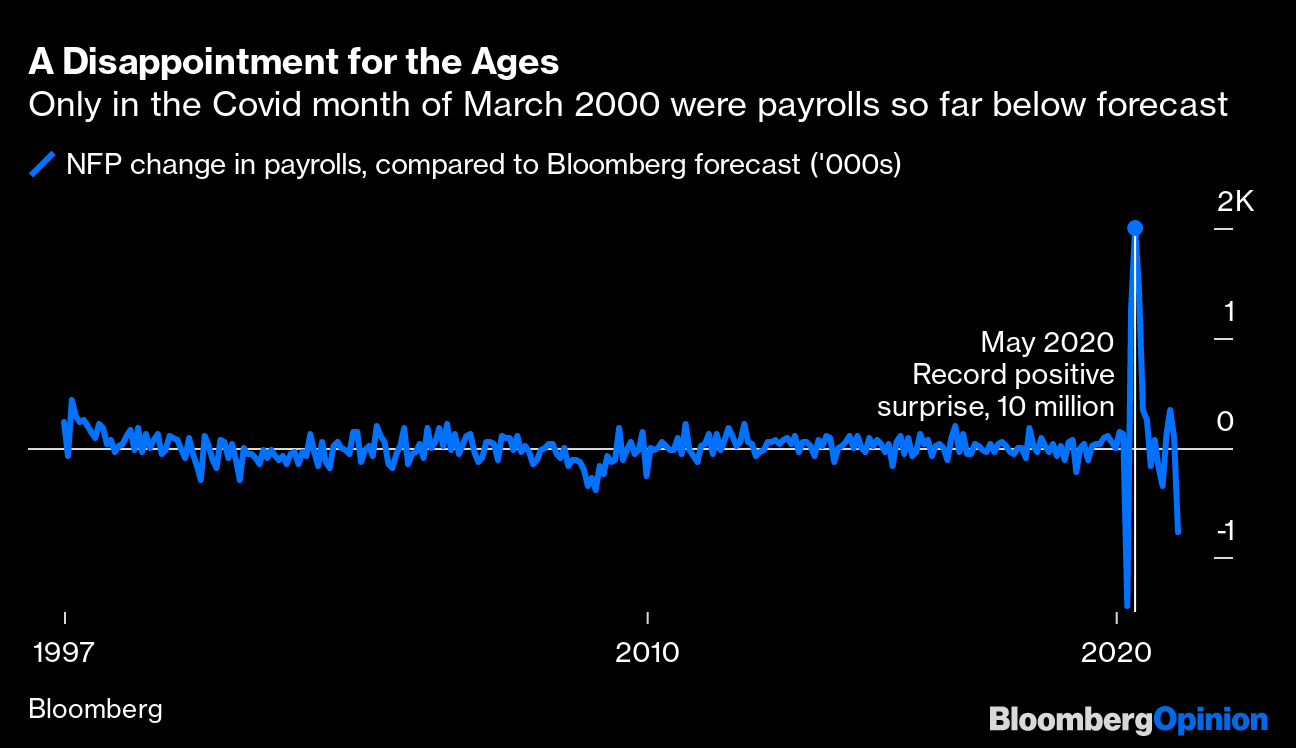

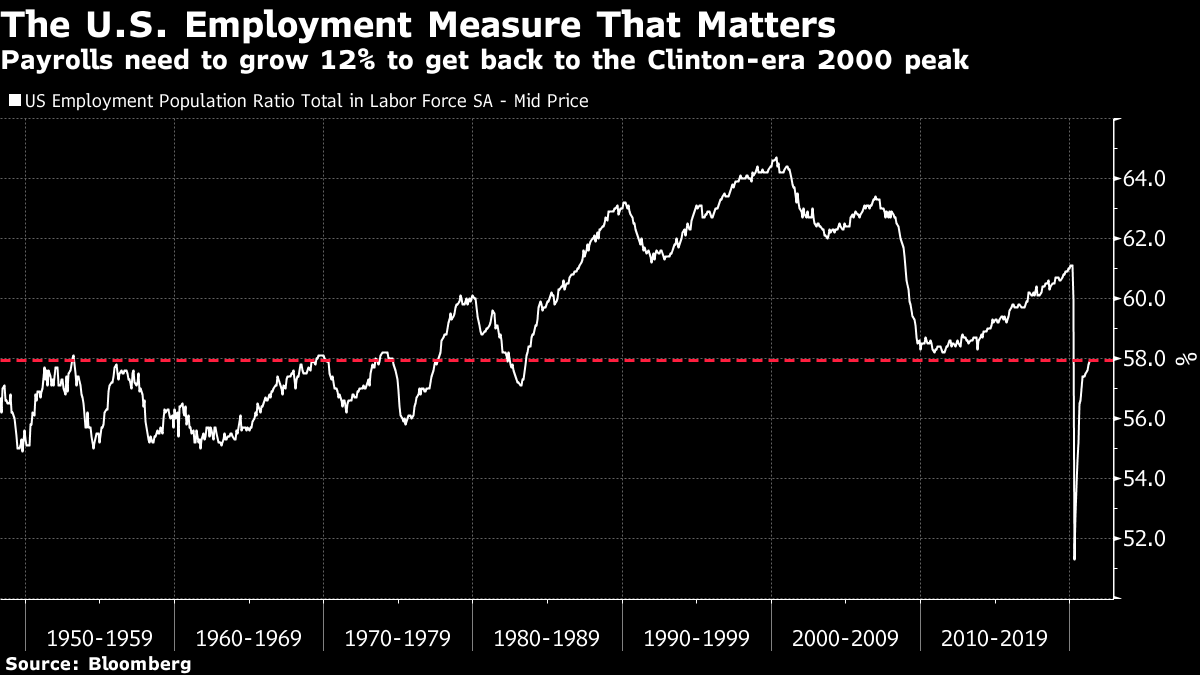

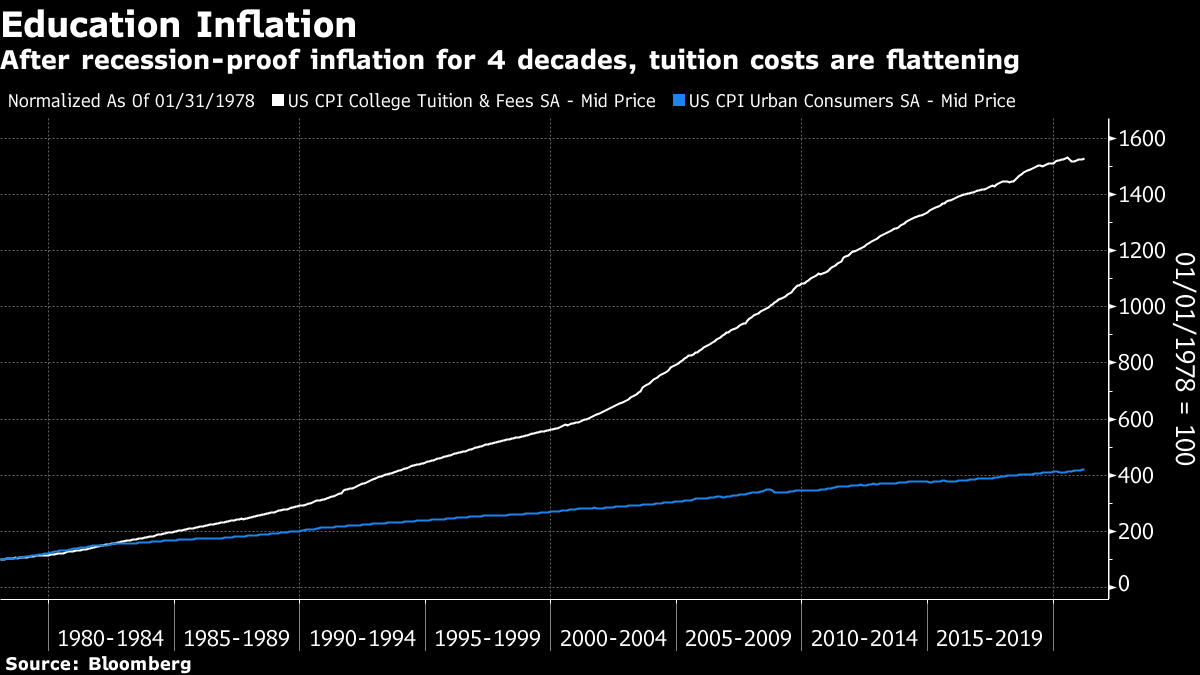

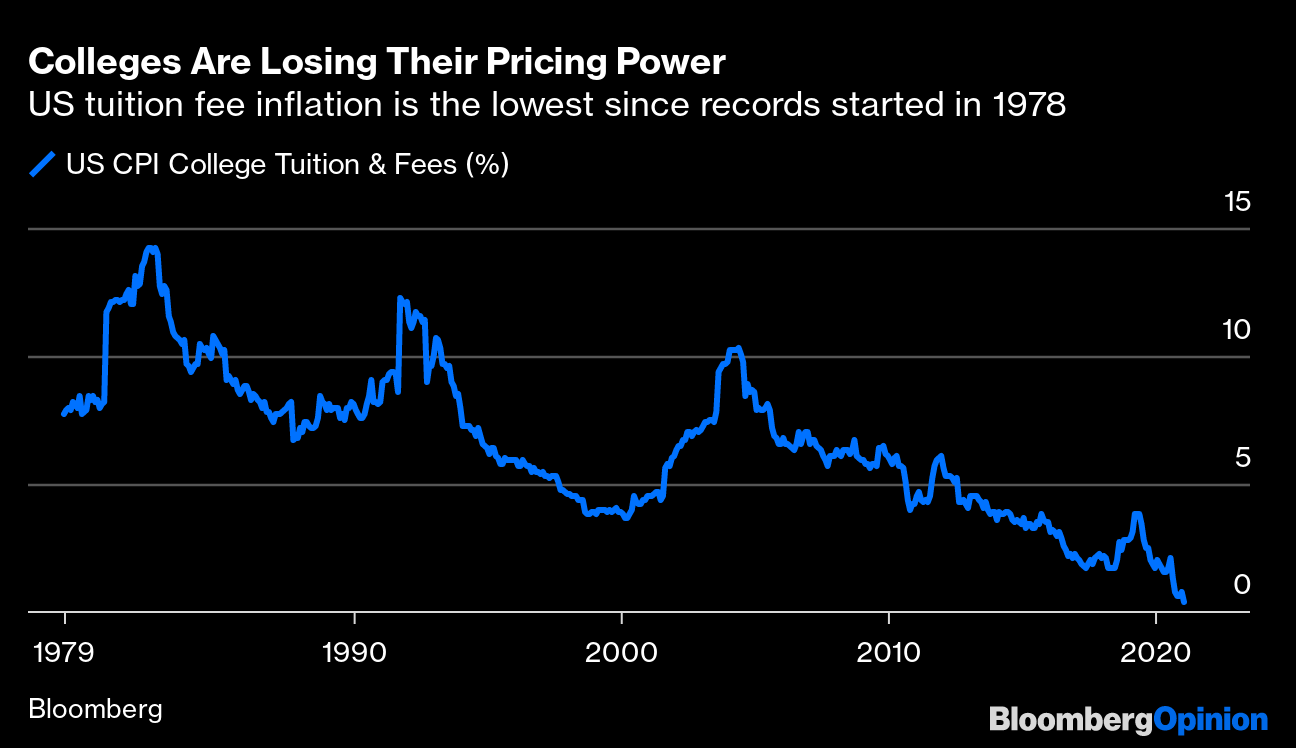

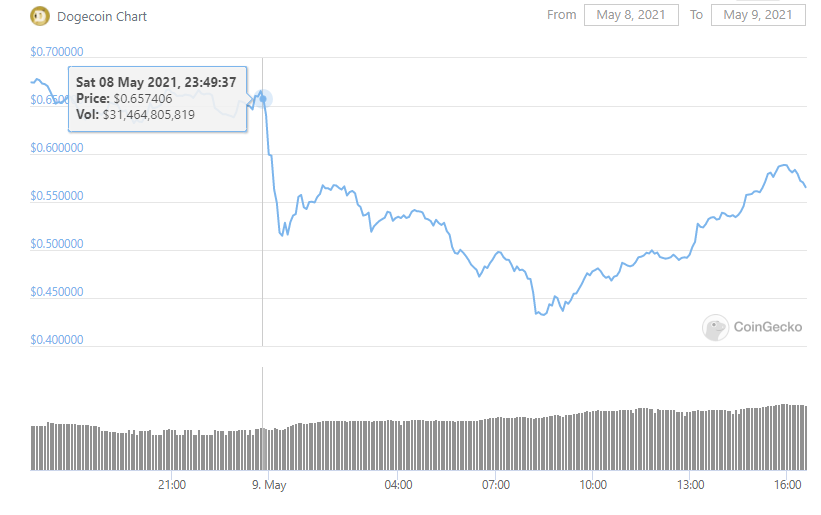

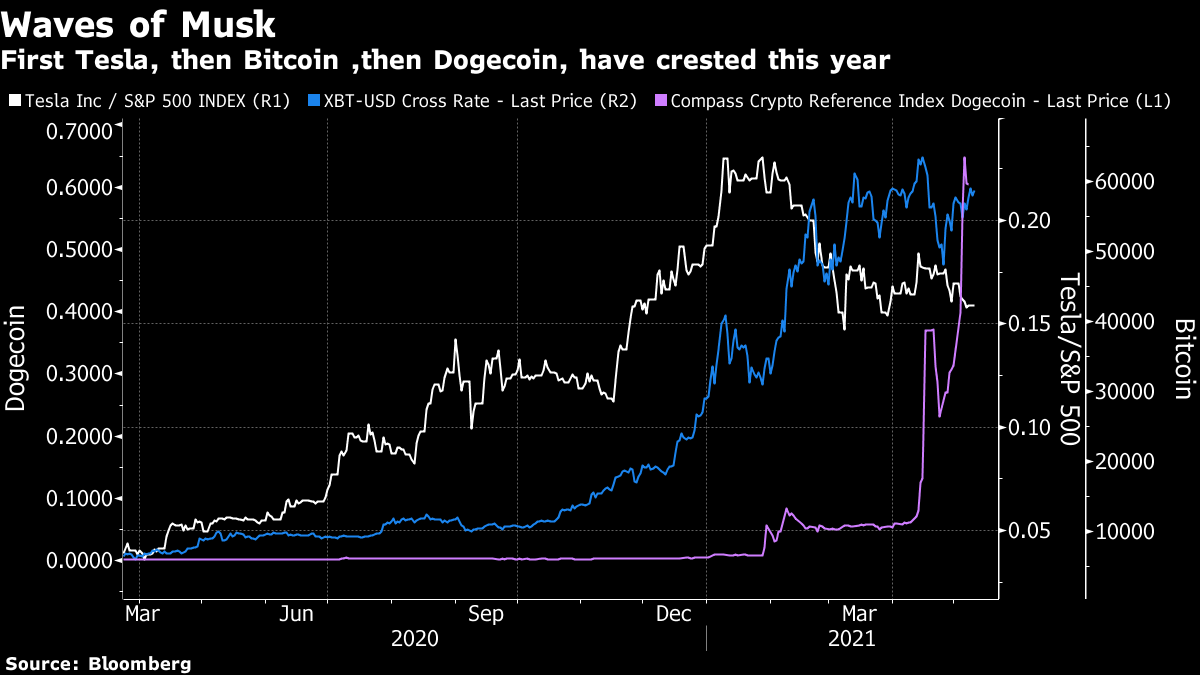

Surprise, Surprise!Did I miss anything while I was away? Well, yes I did. Friday brought the monthly download of U.S. employment data, as is customary on the first Friday of the month, and Bloomberg's survey showed that economists were braced for an increase of almost 1 million in non-farm payrolls. Some expected far better. What happened instead was an increase of only 265,000. With the sole exception of March last year, when the pandemic hit and many forecasters didn't have time to update their estimates, this was the worst negative surprise since the survey started in 1997:  Some of this can be chalked up to the difficulties of accounting for repercussions of an extreme shock. In May last year, economists braced for a serious fall in payrolls, and were amazed when the Bureau of Labor Statistics told them there had been a rise of 10 million. This positive surprise taught us to be careful with data predictions in the Covid era. However, we are now much closer to normality, and this was an extreme miss. All else equal, news that the labor market was weaker than expected should convert into a reduction in forecasts for inflation. With unemployment still high, there is less pressure on wages and hence prices. But the opposite happened. The unemployment stinker was followed by a rise in inflation projections, as derived from bond market breakevens. The prediction for 10-year U.S. inflation is now above 2.5% for the first time since early 2013. Meanwhile the 5-year, 5-year breakeven, covering average inflation between 2026 and 2031, has risen to its highest since 2015:  How can disappointing data have had that result? Because they shifted expectations on how the Federal Reserve will try to navigate the next few months and years. At this point, the Fed cares more than anything about raising employment, and it seems to be focused on the ratio of those employed to the total working age population, a number that avoids confusion over whether people are looking for a job. That figure now stands at 58%. The last time it was this low pre-Covid, the economy was just beginning to recover from the recession of President Ronald Reagan's early years.  The current employment rate is typical of the 1950s and 1960s, when the movement for women to join the workforce was only just starting. To get back to where employment was before the pandemic, payrolls will need to rise by another 5%; to return to the level before the global financial crisis will require a 9% increase; and to return to the level of early 2000, when there was so much excitement about a "new economic paradigm," would require an improvement of 12%. At the margin, Friday's miserable surprise jolted people in the market back to the view that the Fed really will keep rates low for as long as it dares, in the service of pushing up employment. And that increases somewhat the chances of inflation. Equity investors came to the same conclusion, which explains how an awful number, following a week of generally disappointing data, helped power the S&P 500 to a fresh all-time high. Meanwhile, the inflation narrative, which had gone quiet for a few weeks as bond markets stabilized, has been given a new fillip, and anecdotal accounts of higher prices are everywhere. Wednesday's announcement of inflation data for April will be the next big moment. Education DeflationOn the subject of inflation: There is great news for U.S. consumers, although it may be profoundly bad for those trying to manage the finances of higher education institutes. For decades, tuition fees have seen unremitting increases far ahead of the overall consumer price index, and seemingly immune to recessions. This phenomenon is one of the primary exhibits for those who hold that the official CPI understates the true rise in the cost of living; steady escalation in college costs has made entry to well-paid careers ever more expensive.  But now, the trend seems truly to be at an end. In at least one example of a price series that has seen disinflation, and is at risk of outright deflation, a steady decline in college fee inflation has turned into a headlong tumble. The latest number for college fee inflation from the Bureau of Labor Statistics was only 0.4%:  This is a powerful and significant disinflationary force. Colleges are finding it hard to justify charging full-freight for online pandemic classes, while it is far harder to fill places with international students. In such a situation, fee inflation seems finally to have been extinguished. For consumers of college education, this is great news. (Full disclosure: My oldest daughter starts at college in August, and after that I expect to be paying college fees every year until 2031, so a few years of deflation would suit me fine.) For universities and colleges and those who work for them, it is terrible. My impression, after a couple of years' worth of glossy college promotional literature, and real and virtual campus tours, is that much fee inflation has gone into funding improvements in physical stock. Dorm rooms are much nicer than they used to be. Catering is better. And there is also a kind of arms race for the most prestigious colleges to prove that they can do anything. Any number of colleges renowned for liberal arts seem to have gleaming new science centers. All of this is nice, but none of it is necessary. If colleges instead focus on paying and retaining good academics and financing worthwhile research, that would be good. And if the students have to put up with less luxurious accommodation, it might even build their character. Live, From New York, It's the Book ClubIt has been a while since the last Authers' Notes book club. Please accept my apologies. I have, however, lined up a Nobel prize-winner to talk about the next book, which I hope might justify the delay. We'll be reading and then discussing Narrative Economics by Robert Shiller:  This is the most recent book from the man who gave us Irrational Exuberance, and it continues to tap into the emerging field of behavioral finance. Shiller's idea is that we think in terms of narratives rather than numbers, and so markets and economies tend to be driven by popular stories. It leads to some fascinating insights into how bubbles form, take shape and burst. For some previous public discussions on this, you can look at a webinar Shiller held with Princeton University last year, or this debate about the book at the Aspen Institute in 2019. Shiller attempts to explain his idea in one seven-minute video for the Yale School Of Management here. Can we offer a contemporary example of the kind of narrative Shiller has in mind? I believe we can. Try this one: "Brilliant, eccentric entrepreneur re-imagines the electric car, sends rockets to space to colonize Mars, and champions new mega-complex digital currencies that will supplant fiat currency and free us all from governments." That story has shown its power over the last few months. Not only for Elon Musk (yes, I was referring to him) and his company Tesla Inc., but also for cryptocurrencies. Tesla's decision to diversify its holdings into bitcoin helped that currency, and Musk's excited tweets about dogecoin sparked something quite extraordinary. If you haven't read up on dogecoin yet, there are plenty of places to do so. It's a cryptocurrency that was launched as a joke, but has enjoyed spectacular returns this year, largely it appears thanks to Musk. In the 12 months to Friday, it gained 24,000%. Then Musk hosted Saturday Night Live, in what proved to be a galvanizing event for those who follow cryptocurrencies. As celebrities generally do on these occasions, he told plenty of jokes at his own expense. But the crux came when he appeared on the Weekend Update segment as a financial expert named Lloyd Ostertag, and had the same question about dogecoin put to him repeatedly by the hosts: What is it? As a finale, Musk as Ostertag admits: "It's a hustle." You can see the clip here.  Musk (right) as Lloyd Ostertag on Saturday Night Live. Photographer: NBC/NBCUniversal/Getty Images It's all innocent fun, just as the invention of dogecoin was originally a good jape. But this joke prompted quite a market reaction. Here is what happened to dogecoin's price, from the CoinGecko site:  At one point, it was down 35% in 24 hours. That is serious money, given the total value of dogecoins in circulation hit $81 billion last week — equivalent to the market cap of one of the 100 biggest companies in the S&P 500. The dogecoin phenomenon defies analysis. It is inexplicable in any of the terms normally used to explain financial markets. But if you're au fait with the excitement around Musk, Tesla, electric vehicles and trips to Mars, it becomes much more explicable. What it does have to support it is a great story. In other words, we need something a lot like Shiller's "narrative economics" to explain it. And such a version of economics might also help tell us what risks might confront the economy if the story takes a nasty turn and these assets come back to Earth. As it stands, the excitement around Elon Musk seems to come in waves — Tesla peaked relative to the market in January, at about the same time as the GameStop Corp. excitement; then bitcoin hit a period of growth that reached a plateau about two months later; at which point the far more speculative dogecoin took over. Once one narrative loses its power to keep piling on excitement, it seems that people feel the need to move on to the next. Note that this is the first and probably only chart I have prepared for Bloomberg that has three axes. To illustrate this story, I think this is appropriate:  Time will tell whether Musk's appearance on SNL marks the top of some great crypto- and battery-operated mania. It will be a great story if it does, but there are also plenty of ways these exciting assets could come back. What I think is beyond doubt is that this is a great time to start reading Narrative Economics. For the uninitiated, this isn't a "club" with any formal membership. It's a loose attempt to come up with a Bloomberg financial equivalent to Oprah Winfrey's book club. I offer a book to read, give everyone a month to get hold of a copy, and then we hold a live blog discussion on the terminal. A transcript is published on the web. You can send in questions and comments, at any point over the next month, to the book club email address: authersnotes@bloomberg.net. (Note, to avoid confusion, this is an address solely for book feedback; it's not the best way to get in contact with me about anything else.) Ideally, we can get the conversation going ahead of the discussion on the terminal, with Shiller himself and some invited guests, which will happen some time in June. Please get reading. Survival TipsAmid all the excitement on social media about Musk's SNL appearance were plenty of Debbie Downer-style posts saying that Saturday Night Live is no longer relevant. It does indeed seem to be one of those institutions that is doomed always to be thought not as good as it used to be. But it's been a great way to follow the American zeitgeist for almost 50 years now. And it's always been inconsistent. The reason I keep watching is that there is still the chance that amid a bunch of boring skits, you'll find a Cowbell, or some Shwetty Balls, or a cheeseburger, or a young Eddie Murphy delivering pitch-perfect satire on race, or the Godfather in a group therapy session, or discover two lovers discussing their tryst on the island of Santorini. Anyone have others to offer? Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment