Mind the Trade GapAmerica is doing its best to help out the rest of the world. The latest U.S. trade deficit numbers show imports exceeding exports by the greatest dollar amount on record. It's nice of them to buy so much stuff from everyone else at a difficult juncture:  An escalating trade deficit is generally a symptom of economic overheating, but there is little risk of active attempts to use either fiscal or monetary policy to douse the fire. The Biden administration continues to attempt to push through fresh stimulus to fund infrastructure. Meanwhile, minutes from the latest meeting of the Federal Reserve's monetary policy committee dropped strong hints that the central bank really is serious about letting conditions run hot. It described the economy as "far" from the goal of full employment (which is debatable and shows intent to bring unemployment down much more), while my colleague Vivien Lou Chen drew attention to this sentence: "Participants noted 'the path of the federal funds rate and the balance sheet depend on actual progress toward reaching the Committee's maximum-employment and inflation goals.'"

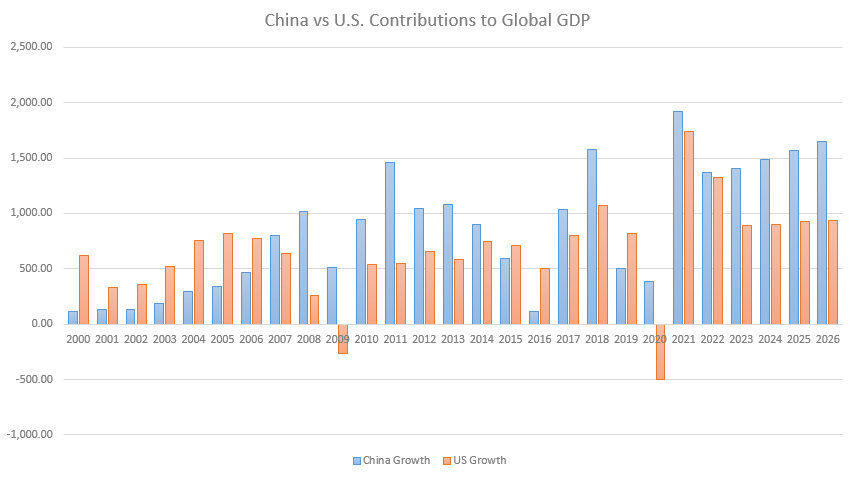

If the Fed really is willing to wait until there are actual signs of a healing U.S. economy, Chen points out that this implies a significant delay. Traditionally, central bankers take into account that monetary policy generally works with a lag of six to nine months; so whenever you thought the Fed was going to start removing the punch bowl, maybe you should move it another six months later. Judging by the very quiet reaction in stock and bond markets, traders had already fully factored in a dovish Fed. Normally, all of this would be great news for emerging markets. Lower interest rates for longer would reduce the risk of protracted fund flows into the U.S. and, of course, the emerging world is the primary source of cheap import goods. The rise in the U.S. trade deficit in the first decade of this century overlapped with a fantastic bull market for emerging assets; times have been much tougher since the deficit returned to more normal levels post-crisis. The latest American stint as the world's buyer of last resort hasn't had the same effect. Very unusually in an environment of global reflation, emerging markets have lagged behind over the last few months:  U.S. growth hasn't helped much. That is largely because there is a reassessment of prospects for China, amid concern that the country will throttle back in the second half to avoid overheating. This may be wise for China, and everyone else in the long run; it's not good news for emerging markets in the short run. The latest Economic World Outlook from the International Monetary Fund, published Tuesday, showed that even with the remarkable rebound for the U.S., the total dollar value of China's growth will still be slightly higher. After a few years when the U.S. led, China is back as the biggest contributor to global growth at the margin, and this drives the emerging markets. The figures are in billions of dollars:  Even with the U.S. dash for growth now under way, China matters more. The leadership is unlikely to do anything too aggressive to tighten before the Communist Party celebrates its centenary in July. What it decides to do after that could have broad ramifications. The world is already in the grip of "divergent recoveries," in the IMF's phrase. The divergence could widen if China opts to rein in its growth once more. Chasing Slow RabbitsBig investment institutions carry immense weight in capital markets, and in society. But they are deliberately making life too easy for themselves, and that ultimately hurts us all. That is the conclusion of a powerful critique of public pension funds and big university endowments, penned by Richard Ennis, called How to Improve Institutional Fund Performance. He finds that much of their effort to improve client returns is wasted, if not actively counterproductive, and that ultimately far too much money goes on fees. As that money comes from sources such as non-profit institutions, taxpayers, and public sector workers paying into their pensions, this is a big problem. It's one that Ennis documents mercilessly. Public Pensions What the legendary Fidelity fund manager Peter Lynch called "diworsification" applies to public pension funds in spades. Ennis found that large funds each use an average of 182 investment managers, commingled funds and partnerships ("portfolios"). Unsurprisingly, this leaves them with median correlation to stock and bond indexes of 98.5%. Typically, pensions pay about 1.25% in expenses, for an approach that renders them virtually incapable of deviating substantially in any direction from the main benchmarks. This problem intensifies in situations where taxpayers find themselves contributing to multiple pension funds. In southern California, for example, Angelenos might find themselves paying toward the pensions of Los Angeles City employees; Los Angeles fire and police; the Department of Water and Power fund; Los Angeles County employees' fund; and the giant state funds Calpers and Calsters, for public employees and teachers. The total number of different funds covered by all these entities would have no chance whatever of logging performance significantly better than the market. How can their overseers tolerate such perpetual weak performance compared to benchmarks? Ennis's most alarming finding is that the funds set their own custom benchmarks: I compared returns reported for the custom benchmarks of 10 of the largest public funds over the decade ended June 30, 2018, with the returns of properly-constructed, passively-investable benchmarks tailored for each of those funds. I found that the former (custom) averaged 149 bps per year less return than the latter (passively-investable) for those funds. Moreover, none of the custom benchmarks had a return greater than that of the corresponding passively-investable benchmark. In other words, there is strong evidence of a sizable downward bias in the returns of custom benchmarks. Accordingly, when reviewing a fund's presentation of its performance relative to its custom benchmark, beware. The fund may be chasing a slow rabbit.

This is a painful example of the "soft tyranny of low expectations." It also makes it very hard to justify big pension funds moving much beyond passive funds. The biggest can take advantage of their scale to negotiate index funds for only 1 basis point; even the small ones can buy Vanguard products like everyone else for about 5 basis points. Endowments The big university endowments have long been the elite of the investment world. Staffed by brilliant academics, and with the kind of long-time horizons that allow them to invest in highly illiquid assets, their every move is followed by the rest of the industry. Particularly since David Swensen took over Yale University's endowment 35 years ago, the "Yale model" has been copied, first by other large endowments and then increasingly by pensions funds as well. The hallmarks of Swensen's approach involve investing in private, relatively inefficient markets where there is a greater chance of generating returns, and taking advantage of endowments' ability to hold illiquid investments. Yale under Swensen pioneered investments in private equity and macro hedge funds, with spectacular success, as well as investments in real assets such as forestry. But it looks ever more as though much of this was due to "first-mover advantage" as Swensen's gifted managers used strategies that were nowhere near reaching capacity. Since the crisis of 2008, Ennis finds, big university endowments have performed worse than public pension funds. For the 12 years to the end of June 2020, he found that public funds had a risk-adjusted return, or alpha, of -1.52% per year. The composite of the biggest endowments kept by the National Association of College and University Business Officers, or Nacubo, had an alpha of -1.87%. The gap, of about 35 basis points, can probably be explained by the extra expense that the endowments take on for investing in esoteric and illiquid strategies. Endowments collectively lagged behind their passively investable benchmarks in all 12 years since the global financial crisis. Of the 43 individual funds Ennis studied, only one had a statistically significant positive alpha, and 16 had statistically significant negative alphas. He suggests that the problem is with the endowment model itself. College funds have enough advantages to make a reasonable attempt at beating the market. As centers of learning, many feel it is their duty to try. But, Ennis says, starting with a top-down asset allocation model and then finding investments to fit each slot is incompatible with taking advantage of their flexibility: Asset-class silos create inflexibility. Once an allocation of, say, 10% of the fund is made to illiquid private equity, the fund manager obliges themself to fill that commitment with the best-looking deals among those that come along. But what if private equity as a class of investment is not a source of value-added? (By the way, private equity, as a class, ceased to be a source of value-added more than a decade ago. So did hedge funds. And private-market real estate, too.) Being opportunistic is a feature of successful value-added investing. But the shape of opportunity changes over time. Absent a genuine role in bringing about efficient diversification, a static allocation to very expensive, largely illiquid, active asset classes without assurance of added-value is no way to run smart money.

Beyond this, endowments have slipped into the "diworsification" trap of hiring too many separate managers. Recruit 10 private equity managers rather than one, and you have a much better chance of selecting the best, but you also improve the odds of picking the worst. Ennis suggests that endowments can enhance their prospects of outperformance by doing away with fixed top-down asset allocations and reducing the number of active managers. They can also use passive funds (another concept that grew out of academic research) as the core of portfolios to reduce costs. Survival TipsLife in a multi-generational workplace can be difficult. I often find it unnerving to be working with colleagues who weren't born until after my 30th birthday. And doubtless millennials might be a little uncomfortable working with people who still talk about, and used to use, things like cassette tapes, typewriters, fax machines, Palm Pilots, Blackberries, rotary phones and even postage stamps. It's often the cultural references that are most difficult. Thankfully, my colleague Mike Regan who, like me, is a "senior editor" in the Bloomberg markets team in more ways than one, has a solution. He has put together a list of movies for recent graduates to watch so they know what the old men in U.S. workplaces are talking about. Here are the 40 movies that he recommends under-30s should watch next week: 1. Caddyshack 2. Animal House 3. Fletch 4. Godfather 1 5. Scarface 6. National Lampoon's Vacation 7. Blues Brothers 8. Jaws 9. Star Wars 10. Wall Street 11. Meatballs 12. Pulp Fiction 13. Raising Arizona 14. Cannonball Run 15. Platoon 16. Full Metal Jacket 17. At least one of the "Any Which Way But..." series 18. It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World 19. The Natural 20. Hoosiers 21. This Is Spinal Tap 22. Trading Places (finance majors, watch this twice) 23. Beverly Hills Cop 24. Better Off Dead (arguably should be higher) 25. Grosse Point Blank (ibid) 26. The Jerk 27. Monty Python and the Holy Grail 28. Monty Python's Life of Brian 29. Monty Python's Meaning of Life 30. Breakfast Club 31. Risky Business 32. Fast Times at Ridgemont High 33. At least one of the Pink Panther series 34. Top Gun 35. Forrest Gump 36. Stripes 37. Field of Dreams 38. Tin Cup 39. Weekend at Bernies 40. Happy Gilmore

It's a good list, although of course we can all raise issues. I was perturbed that Mike had his millennials watch another 36 movies after The Godfather without getting to the sequel, which is arguably better. And I'd be inclined to make Trading Places compulsory for anyone who wants to work at Bloomberg, or frankly anywhere in financial services. But it's a great start. More contributions gratefully accepted.

So, millennials, that's your viewing for the next seven days. There'll be another list next week. And thank you Mike.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment