Wall Street's Taxing DayStock markets don't like it when politicians say they are going to raise capital-gains taxes. This should come as no surprise to anyone, and so Wall Street's response to Thursday's Bloomberg News exclusive that President Biden is planning a big hike in CGT was predictable. No prizes for working out exactly when that story was published after looking at this intraday chart of the S&P 500:  The president, who has ambitious plans to raise spending, campaigned last year on a platform that included a big CGT increase. Investment strategists had already done the mathematics for the stock market. Writing the week before last year's election, David Kostin, chief U.S. equity strategist for Goldman Sachs Group Inc., predicted exactly the rate flagged in Bloomberg's story almost six months later: Long-term capital gains and qualified dividends are currently taxed at a maximum rate of 20%, along with a separate 3.8% tax on investment income. Vice President Biden has proposed taxing these as ordinary income for filers with over $1 million in annual income. This would roughly double the tax rate on capital gains and dividend income from 23.8% to 43.4%.

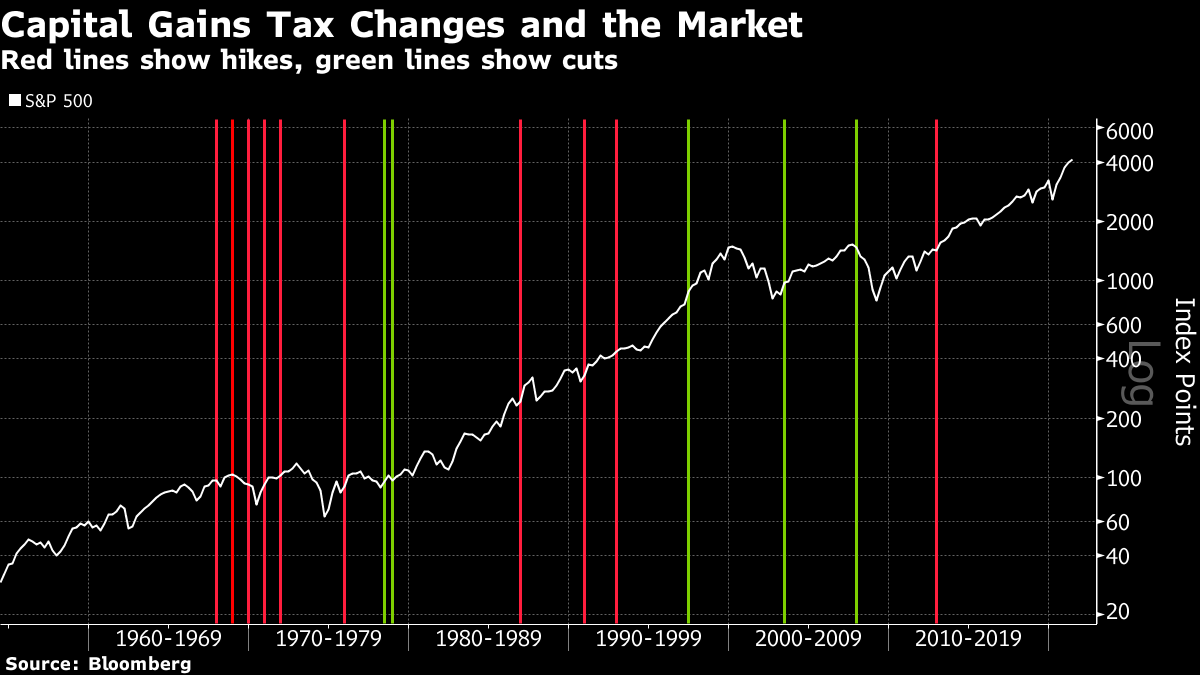

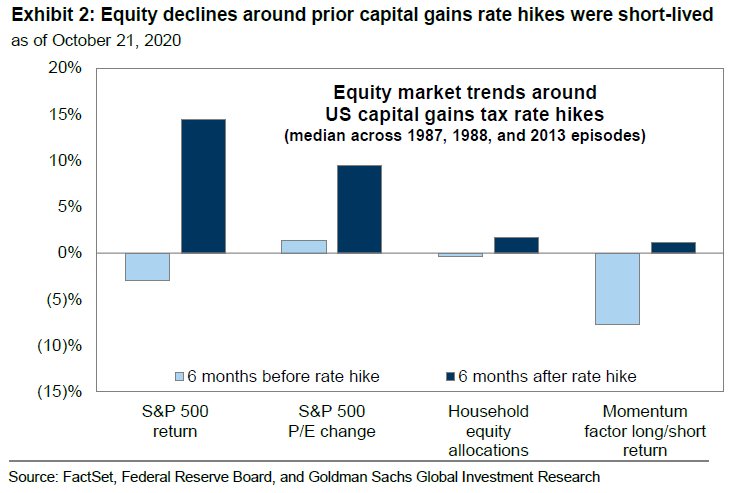

It should be no great surprise that capital-gains taxes will come into focus, as these have a far greater impact on the wealthy than the poor. They are the ones who have enough wealth to generate capital gains in the first place; tax-planning programs that try to convert income into capital gains can help the wealthy reduce their tax bill (which is unpopular); and most Americans hold most of their stocks through tax-privileged vehicles such as 401(k) plans, and are unaffected. In the current political environment, anything that counteracts inequality will be more popular with Democratic legislators and their political base. Rather, it was the scale of the rise that came as a nasty surprise. The effective top rate of 43.4% (including a levy for Obamacare) is where the Biden administration will start the bidding, according to Bloomberg News. That's a lot. It could conceivably have been higher, as this is the start of a negotiation, and economists at Princeton University argued last year that an even higher rate, of 47%, would maximize revenue from the tax. What are the direct effects of a CGT hike? If you were thinking of selling shares anyway, it makes far more sense to sell them before the end of the year. There is also an incentive for "bed-and-breakfasting" — selling a position to crystalize a gain for tax purposes and then buying it back. That should help ensure an exciting end to the year. But it's not clear that higher CGT does anything more than bring sales forward. The way the market handled the last major CGT increase, at the end of 2012, is instructive. As it grew clear that higher capital gains taxes were coming, the S&P 500 languished and went sideways for the last few months of the year, closing roughly where it had been in March. Then 2013 turned out to be a great year; stocks started their rally at the beginning of January and never really stopped:  If it becomes clear that some tax increase is going to happen, then some broad repetition of this pattern seems more likely, with returns that people might have been expecting for this year postponed until next. Longer history tends to confirm this. Capital-gains taxes can be seen coming, which makes them easier for markets to deal with. Beyond that generalizations are difficult, even though there is plenty of data. The level of tax you pay on gains will have an effect on the returns you make personally, but they aren't so fundamental to the overall level of the market. In the following chart, I marked all CGT hikes in red, and cuts in green. In the late 1960s, steadily rising CGT overlapped with growing problems for the markets, but both owed much to the economy's difficulties. Two classic examples that show CGT doesn't overcome other issues for the markets came in 1987, which began with a tax hike, and was followed by an epic rally and then a crash, and 2008, which saw markets steadily slip for months until crashing amid the crisis, despite starting the year with a CGT cut:  Kostin of Goldman Sachs crunched the numbers for the last three CGT hikes, from 1987, 1988 and 2013. Stocks do indeed tend to fall in the run-up to the change, but more than make up for it thereafter. Earnings multiples increased slightly before those rises, but did better in the six months afterwards. And households sold a little before the hikes, but more than made up for it. The only lasting effect appears to be on momentum stocks. They have the highest gains to be generated, and will therefore suffer the most from unexpected selling:  Momentum stocks have had something of a correction in recent months however, so it is unlikely that the tax change will have a major effect on them. That means Kostin's summing-up from six months ago should still stand today: Using Federal Reserve data, we estimate the wealthiest households now hold around $1 trillion in unrealized equity capital gains. This equates to 3% of total US equity market cap and roughly 30% of average monthly S&P 500 trading volume. However, the trend of net equity selling and falling stock prices around capital gain rate changes has usually been short-lived and reversed during subsequent quarters. In 2013, although the wealthiest households sold 1% of their assets prior to the rate hike, they bought 4% of starting equity assets in the quarter after the change and therefore only temporarily reduced their equity exposures in order to realize gains at the lower rate. Total household equity allocations demonstrated a similar pattern around the two preceding capital gains tax hikes.

So if anything it is surprising that the Bloomberg story had so much of an effect, beautifully written though it was. Some of this comes from growing awareness in the investing community that the Biden administration's spending is going to have a lumpy effect on fiscal policy. The economic benefits of building big physical infrastructure projects take time to have an effect; the taxes to pay for them have an immediate and earlier impact. There is also some reason for apprehension about the end of the year. The CGT hike is going to happen in some form, and it will weigh on the market then. If the strong economic data don't show signs of slowing, that could be about the time that the Fed develops cold feet about overheating and starts to tighten monetary policy. So there are reasons to be nervous about the last few months of this year — even if there wasn't much reason to sell off on a Thursday afternoon in April. Survival TipsIt's time to confess a guilty pleasure. There is a lot of fun to be had in listening to egg-headed podcasts. I don't mean the kind that has become a work of art, with sound effects and famous actors, but the more deliberately austere type that feature someone wonky speaking to somebody else who's wonky, or possibly even just talking into a microphone for half an hour. Or an hour. There's something soothing about it, and podcasts like this are a great way to fill gaps in your knowledge. So, here are some of my favorite unadorned and unashamedly intellectual podcasts, to which I would give five stars. I'm afraid there's a bit of a bias toward British voices, which suggests I might also be using them to deal with occasional pangs of homesickness: Dan Snow's History Hit — Snow is a public historian, and son of the famous BBC journalist Peter Snow. He produces five episodes a week, in which he interviews a historian about their work. It ranges all over the place, with plenty of non-British voices. The last week included episodes on Shakespeare's Shoreditch Theatre, Roman Prisoners of War, Lessons from the Antonine Plague, and "Lady Mary and the First Inoculation" on the pre-history of vaccination. I even wrote up a newsletter from the episode on the Irish Potato Famine. Talking Politics History of Ideas — in which David Runciman, a Cambridge University politics professor, offers a series of 50-minute monologues on great political thinkers. There are episodes on John Rawls and Robert Nozick, and historic titans like Hobbes and Rousseau. But Runciman, who does a great job of building up a case and explaining his thinkers' key insights, also chooses some more surprising candidates, such as Samuel Butler, Frederick Douglass or, most recently, Judith Shklar and her argument on why we shouldn't be angry about hypocrisy. In Our Time — veteran arts journalist Melvyn Bragg interviews three university professors on some random subject. The topics are all over the place, and range into science (there was a lengthy discussion of the French mathematician Laplace earlier this month), as well as history and the arts. It can learn you up in a hurry on subjects you never knew interested you; for Points of Return readers, the episode on David Ricardo is interesting, and told me a lot I didn't know. Deep Background — this features my intimidatingly intelligent Bloomberg Opinion colleague Noah Feldman, who finds time to do a weekly podcast in the gaps between his job as a professor at Harvard Law School. In each podcast he interviews one guest. He's most interesting when he hones his analytical mind on subjects off his usual beat. This week's answers the question "Is Crypto B******t?" They're worth giving a try. Have a good weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment