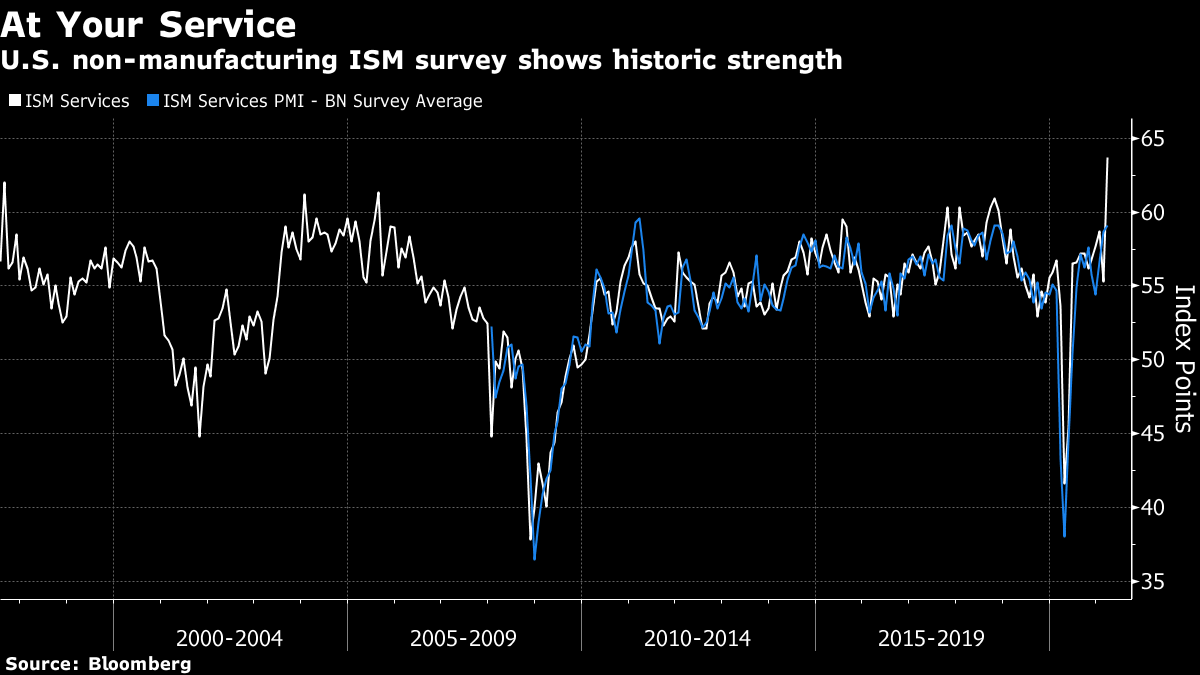

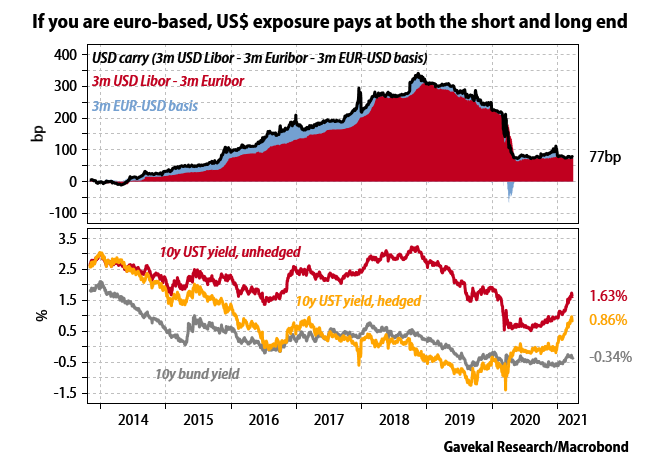

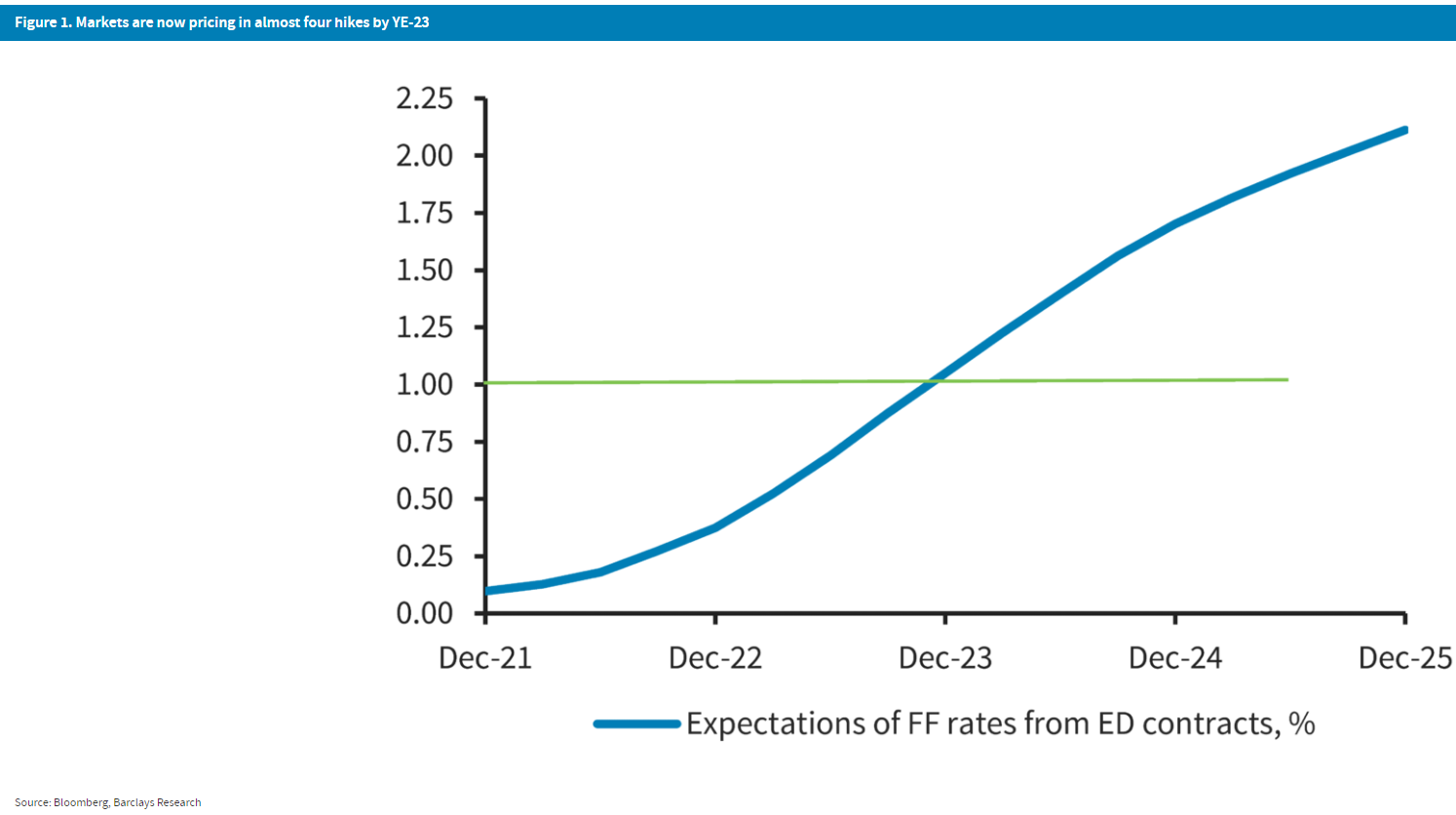

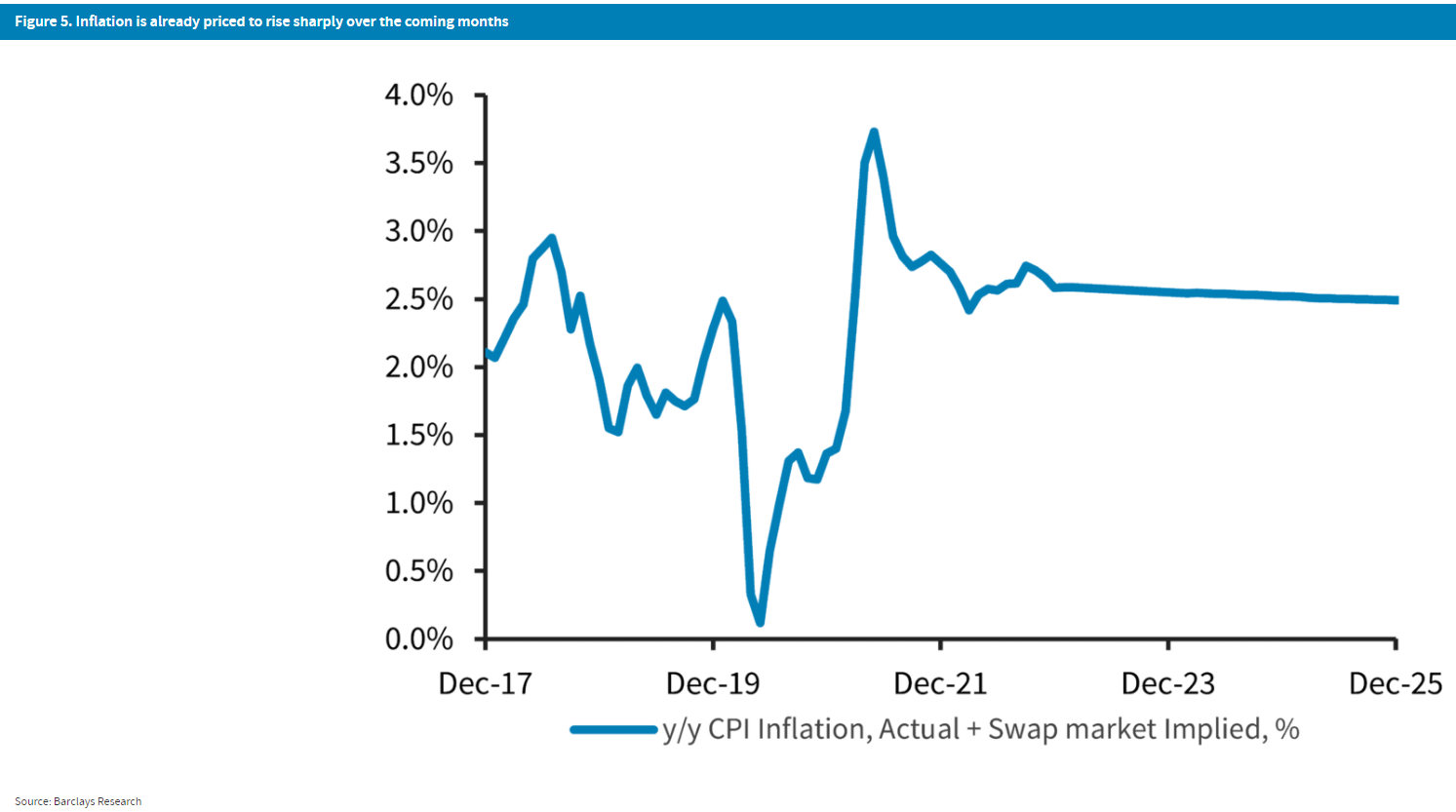

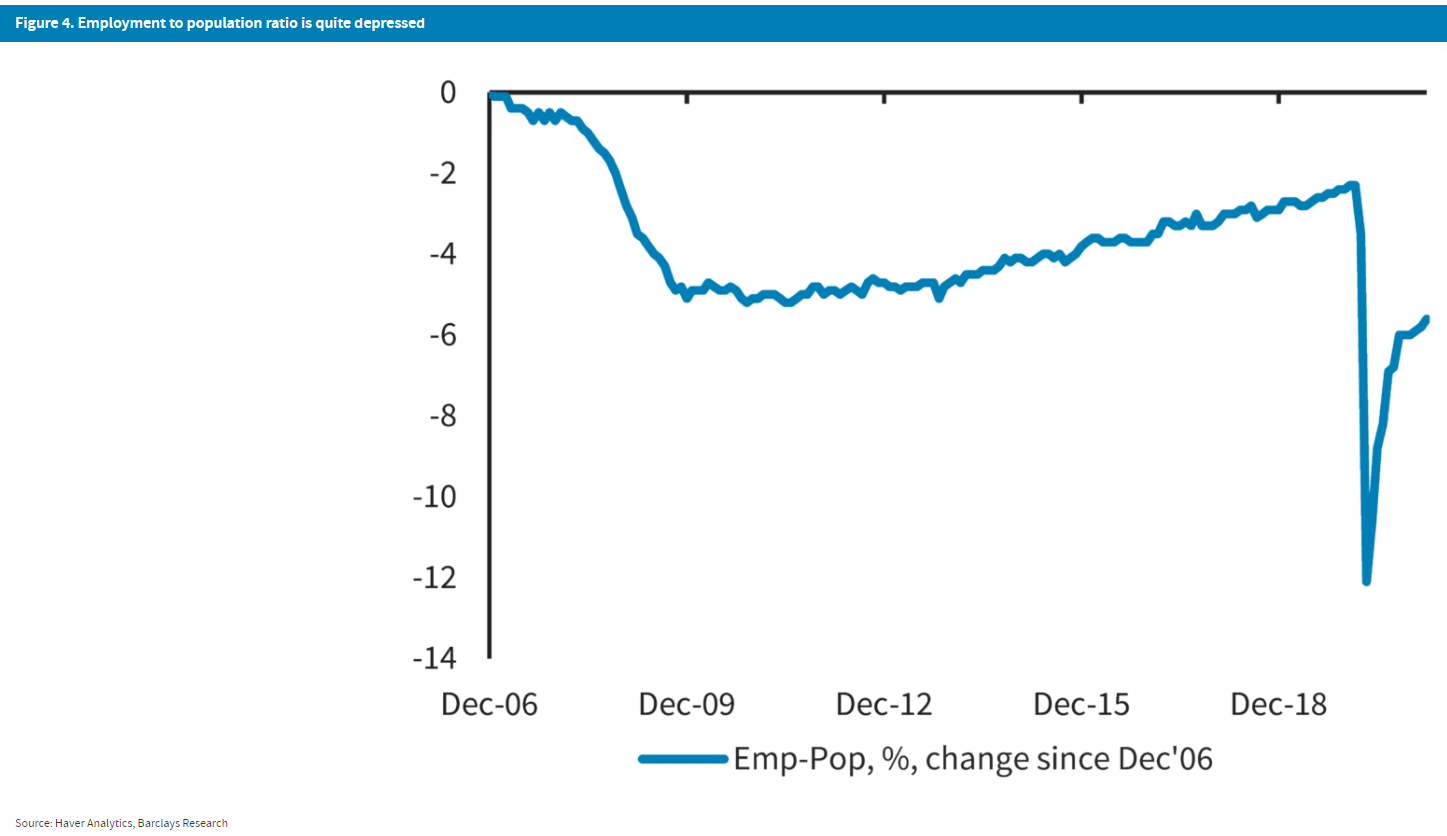

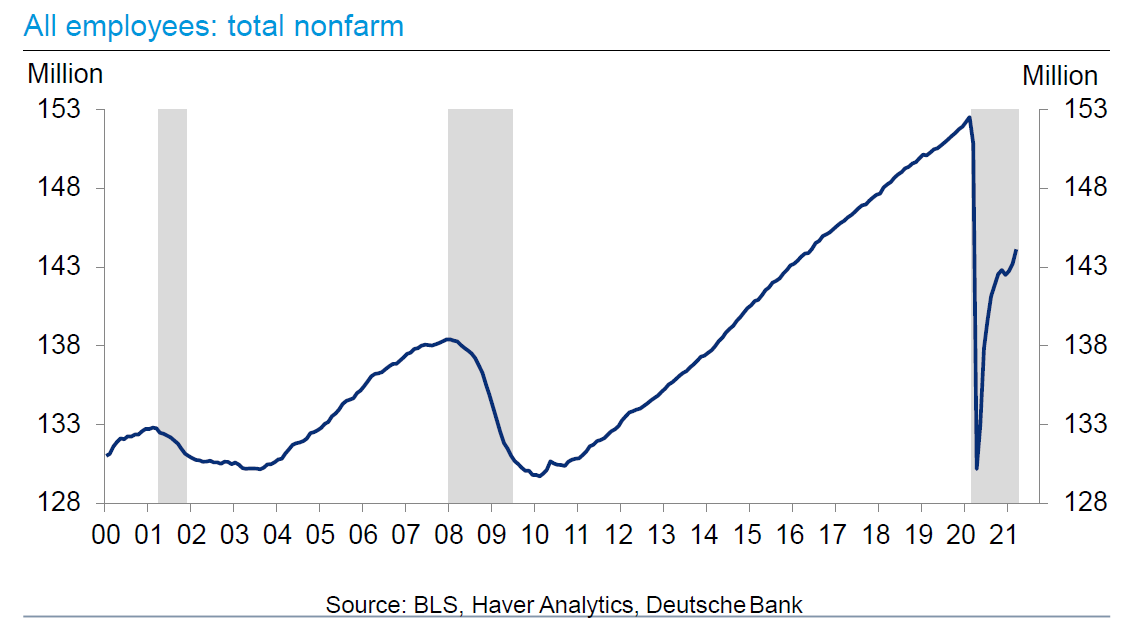

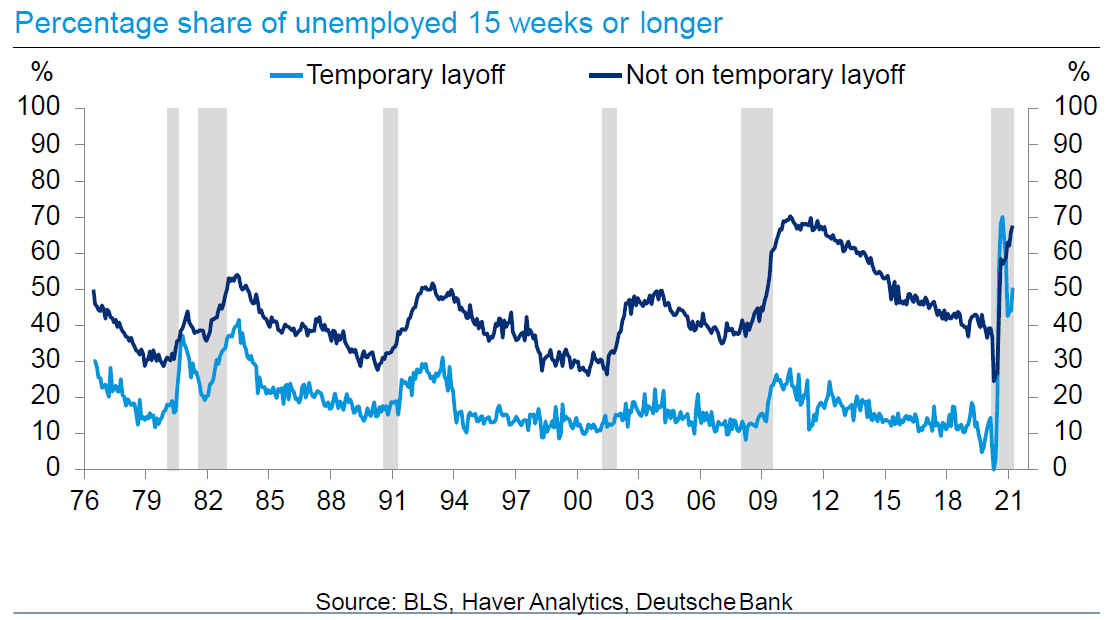

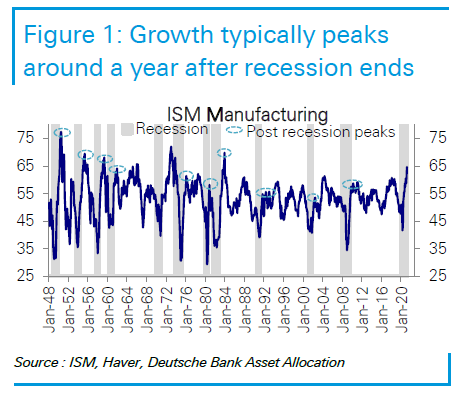

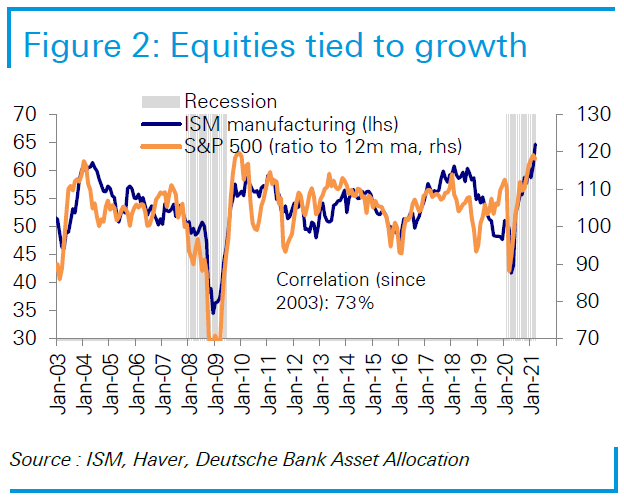

As Good as It Gets?April is showering the U.S. with economic good news. The last two days of last week brought startling good numbers on manufacturing from the ISM purchasing managers' survey, followed by an excellent jobs report on Good Friday. The question was whether the services sector, more directly affected by the pandemic slowdown, would be able to revive to the same extent. On Monday, the ISM services survey for last month came in with the highest figure since it started in 1997, while beating expectations by the biggest margin since Bloomberg began compiling economists' estimates in 2008. So, yes, the services sector is doing well too:  There is a sting in the tail. Does growth on such a scale lead to overheating in the form of inflation? Again, the answer appears to be yes. ISM surveys detail the percentage of companies that say their costs are rising, and the percentage that say they are falling. Among manufacturers, those with rising costs exceeded those where they are declining by 70%; for services, the figure is 50%. We always knew there would be an inflation scare in the early part of this year, as the cratering of activity 12 months ago drops out of annual comparisons; these numbers suggest that such fears are rational, even if we cannot yet tell whether they have come true:  We all know what investors should do when inflation risks rise and the economy looks like it might overheat: sell bonds. Inflation will naturally gnaw away at the value of fixed future income streams. So yields will rise. That gives rise to the notion that you can have too much of a good thing; if inflation takes off, rising bond yields will choke growth. That certainly hasn't happened yet. U.S. stocks have set another all-time high, and growth in equities relative to bonds continues to be phenomenal:  The strong U.S. data have also re-powered U.S. stocks compared to the rest of the world. The dollar has strengthened again, while the stock market is outperforming the rest of the world comfortably, after a brief break late last year:  So, this was a classic rotation toward growth. With one exception. The dog that didn't bark There is one strange part of this narrative, which is that bond yields haven't been hit hard by April's strong data. They have come a long way in a hurry, but it is intriguing that both inflation expectations and nominal yields have edged down a little since the beginning of the month, as of the time of writing:  Equities have broken records not because bond yields have risen in response to strong growth (a popular narrative), but because the data have been good and yet yields haven't climbed. Growth without having to pay for it with higher interest rates is obviously nirvana for stocks. But how has this happened, and how long can it last? There are a number of explanations: Treasury bonds are a buy for foreigners now For a while, it was so expensive to hedge the possibility of a falling dollar that 10-year Treasuries weren't appealing for European investors. U.S. short-term rates were simply too high, compared to virtual zero rates in Europe. Now, with the Federal Reserve keeping shortest-term rates down while allowing longer yields to rise a bit, that calculation has changed. Hedged 10-year U.S. Treasuries offer a much nicer return than equivalent bunds. Foreign buying naturally limits the increase in U.S. yields. This chart from Nick Andrews of Gavekal Research Ltd. neatly illustrates the mechanics:  The market is already pricing in an aggressive Fed OK, "aggressive" might be a strong word for it, but Barclays Plc's Anshul Pradhan shows that fed funds futures now price in four rate rises by the end of 2023. This is far more hawkish than the Fed's "dot plot" of forecasts from its governors, so the market is betting that the central bank will be forced to tighten before it wants to:  It does this despite a sanguine attitude to inflation. The following chart, also from Pradhan, shows the implied "headline" (including fuel prices) inflation rate derived from the swaps market. Everyone is alive to the fact that base rates will give us scary-looking inflation of 3.5% later this year; but the market expects the headline figure to settle down at about 2.5%. As consumer price inflation tends to be a few tenths of a percentage point higher than the PCE measure that the Fed prefers to target, this shows the market thinks the Fed will get what it says it wants — inflation averaging a little above the target of 2% for a while, without accelerating.  So the market is already adequately pricing in a brief inflation shock, and a ratchet up in the standard rate thereafter, while it appears to be overpricing the risk of Fed hikes. That gives an incentive to buy Treasury bonds (and push down their yields). The labor market won't let the Fed stop The Fed says it really cares about employment. If so, it should be happy with the unambiguously positive trends in the U.S. jobs market. However, the numbers also show that it will want to stay very easy for a while. That could keep downward pressure on yields. First, if we look at employment as a share of the population (without adjusting for those who aren't making themselves available for work), joblessness is still worse than it was at any point in the last recession:  And if we look at the total number actually employed, in a chart from Matthew Luzzetti of Deutsche Bank AG, we see again that there is a lot of improvement to go yet:  We know the Fed would like unemployment to be lower. But are we in danger of a labor market so tight that it pushes up wages, costs and inflation? Quite possibly not. As this chart from Luzzetti shows, the percentage of those not officially on a temporary layoff who have been jobless for 15 weeks or longer is disturbingly high and still rising:  It is long-term unemployment that really rots people's lives, and also attacks competitiveness and productivity. There is also slack in the number of people who are working part-time for economic reasons but would prefer to be full-time. The strong figures at present in part reflect efforts by employers to diminish employees' pain. Growth can continue from here without putting pressure on wages and prices:  The top could be in A final issue, pointed out by Deutsche Bank's Bankim Chadha, is that this could be as good as it gets. Generally, the ISM Manufacturing peaks within a year of the end of the recession, and last year's remarkable slump was over very quickly. To be clear, economic conditions were still miserable, but growth resumed by the end of the spring. Looking at the record of the ISM in the cycles of the 1950s and 1960s, which were much shorter than the recessions of the last decades, suggests that we are probably at or already close to the top. This doesn't mean that the economy will immediately lapse into a recession, but it does mean that the speed of the recovery will slow, and it is this speed of travel that tends to matter to markets:  Over time, stocks have tended to move in tandem with the ISM manufacturing index, which again makes sense. The ISM is intended to be a leading indicator of growth, and equities are attempting to discount future growth. Over the last 20 years, the correlation has been very close, so it is to be expected that a blowout ISM number would immediately be followed by a blowout in stocks:  The bad news is that once the top is in for the ISM, equities almost always pull back. This isn't necessarily the beginning of a bear market or a crash, but they can be expected to have a bumpier ride before long. As for bonds, if investors are looking forward as they should be, then they may also be judging that enough growth has been priced in for now. If they believe that the top for growth is already in, or fast approaching, then they can more easily look through numbers as strong as the data of the last few days. There has been justified excitement about the speed with which bond yields rose in the first quarter, which was the fixed-income market's worst three months in decades. There is also excitement that stocks managed to rise regardless. But the story of the latest leg up is that bond yields have stopped their ascent, at least for a few days. There is some chance that faith in a dovish Fed, and the natural market balancing mechanisms that attract buyers when yields rise, can keep them where they are even if reflation continues. If that happens, equity bulls can enjoy themselves a little while longer before the rate of growth peaks. Survival TipsAs the Biden administration tries to persuade Congress that it would be wise to spend another $2 trillion on infrastructure, we can expect to hear a lot about whether it is responsible to take on all the debt that will be needed to fund these projects. For a passionate argument that this would be OK, I pass you over to this video by a fellow Englishman in New York, John Oliver. It's genuinely funny, and his point is well taken that it will be impossible for Republicans to oppose this without walking into charges of hypocrisy after the cheerful way the last two Republican presidents ballooned the deficit. It would be great if someone could come up with a similarly clever and funny argument against deficit economics. I'm happy to take submissions. For those who haven't watched Oliver before, family favorites include his takedown of the Miss America beauty pageant, an amazing piece on the leader of Turkmenistan, and this riposte after he successfully fought off litigation from a West Virginia coal mining executive. You might not agree with him, but there's real journalism in what he does, and he's done a great job of bringing the British sense of humor to the U.S. (and please don't watch if you dislike four-letter words). Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment