Take This SeriouslyFour years ago, corporate tax reform was on the agenda, but few took it seriously. What happened next? Tax reform did come through by the end of the year, under President Donald Trump and a unified Republican Congress, but it was in a very different and less ambitious form than first mooted. That led to a brief but spectacular melt-up in stock markets. It didn't lead to any great lasting changes for the economy. Bear all this in mind as the process of determining how the Biden administration will pay for its hugely ambitious spending plans starts working its way through Congress. The chances are that something will happen, and that it could have a big impact on markets, whatever the ultimate impact on the economy. It will be a while before there's any clarity on what can pass, and much will depend on Democratic moderates in the Senate, led by Joe Manchin of West Virginia. But that doesn't mean that it is too soon to start looking at what might happen under different scenarios. Here's a brief guide: What is being proposed? There are several moving parts, all subject to negotiation. The most important are: - The statutory rate of corporate tax, which could rise to 28% (many think a 25% compromise is more likely);

- The Global Intangible Low-Tax Income, or GILTI, tax, introduced under Trump to make it harder to shelter overseas intangible profits, which could be expanded significantly;

- A Minimum Book Tax, to make sure everyone pays something, which could be 15%.

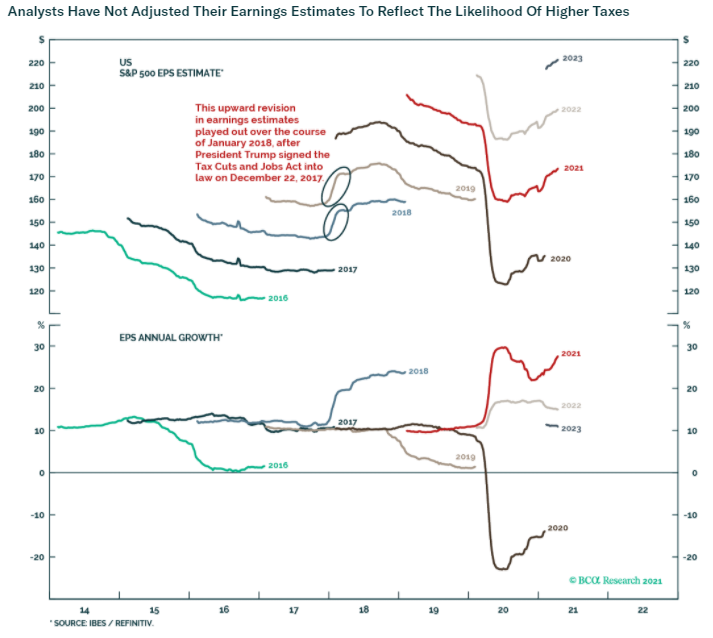

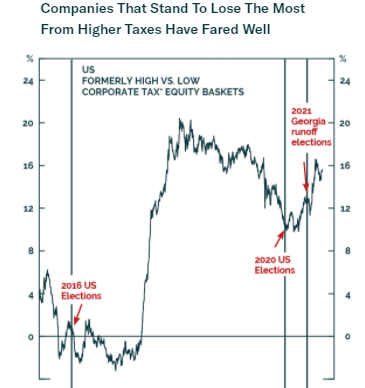

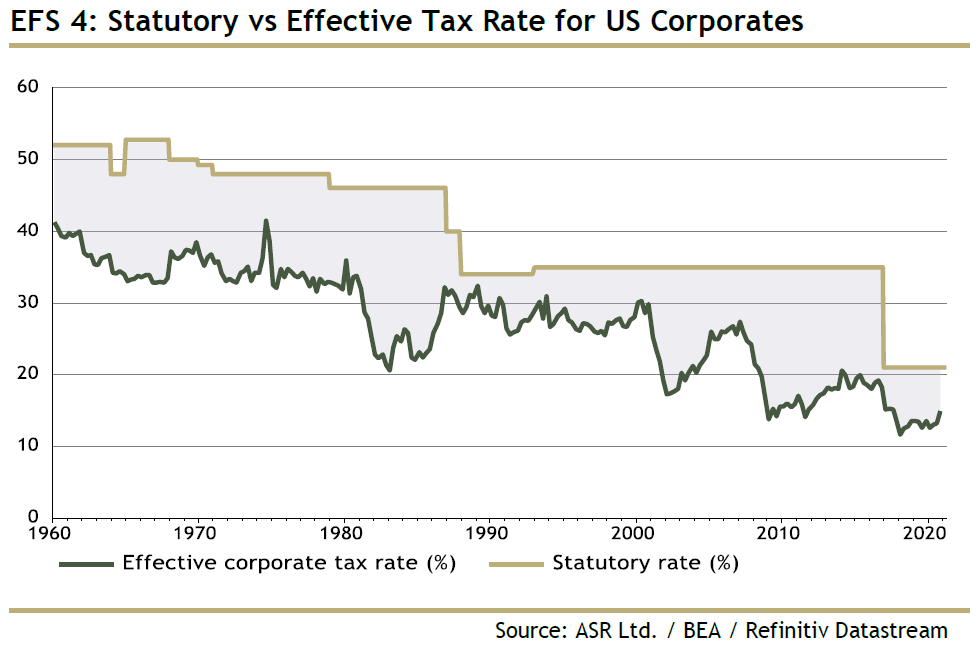

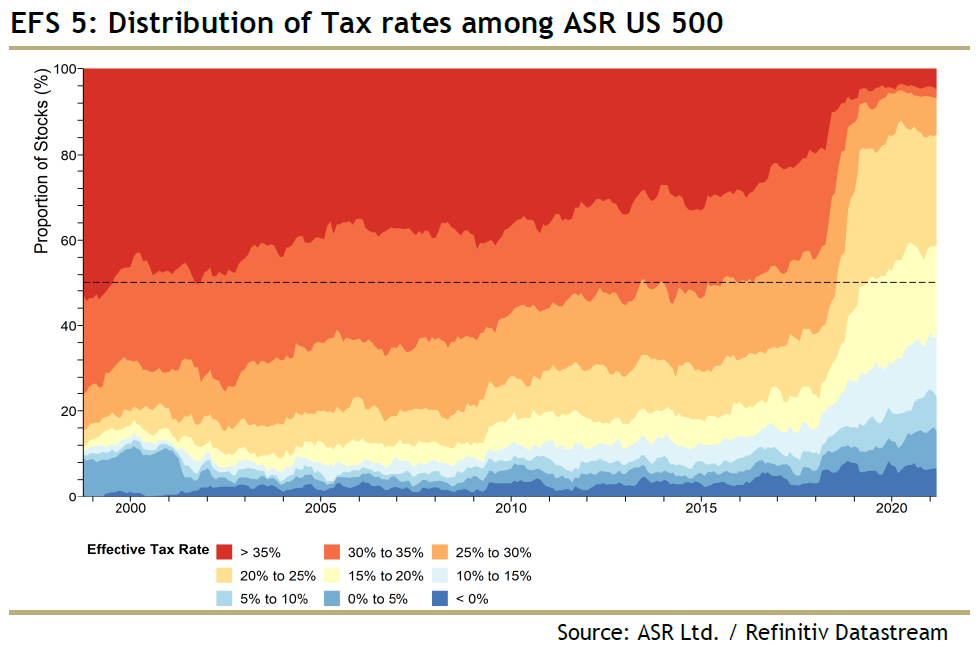

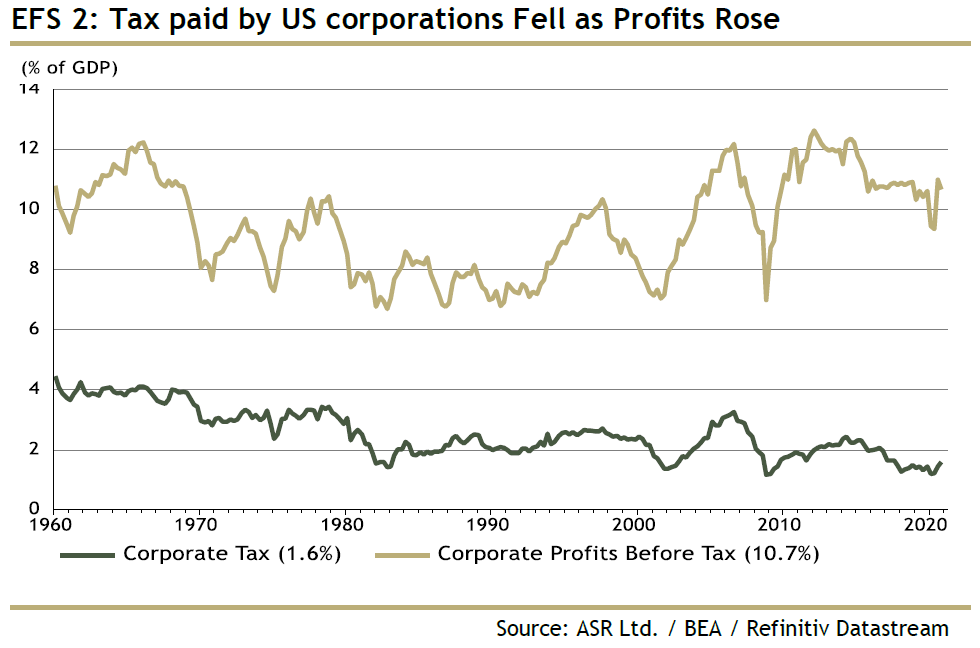

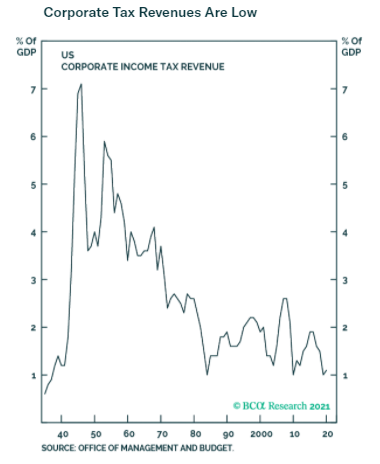

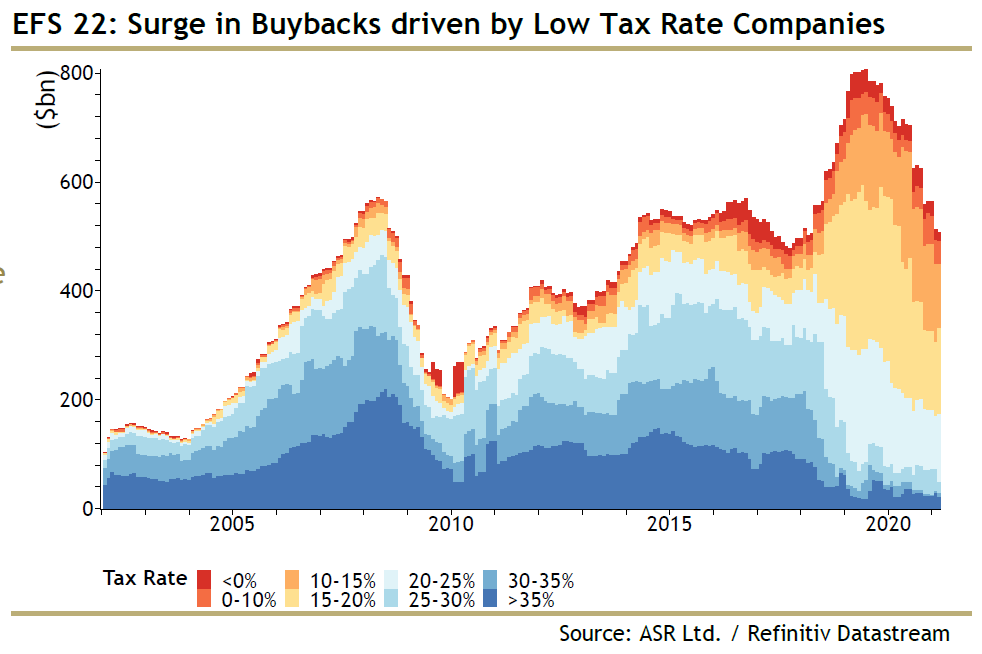

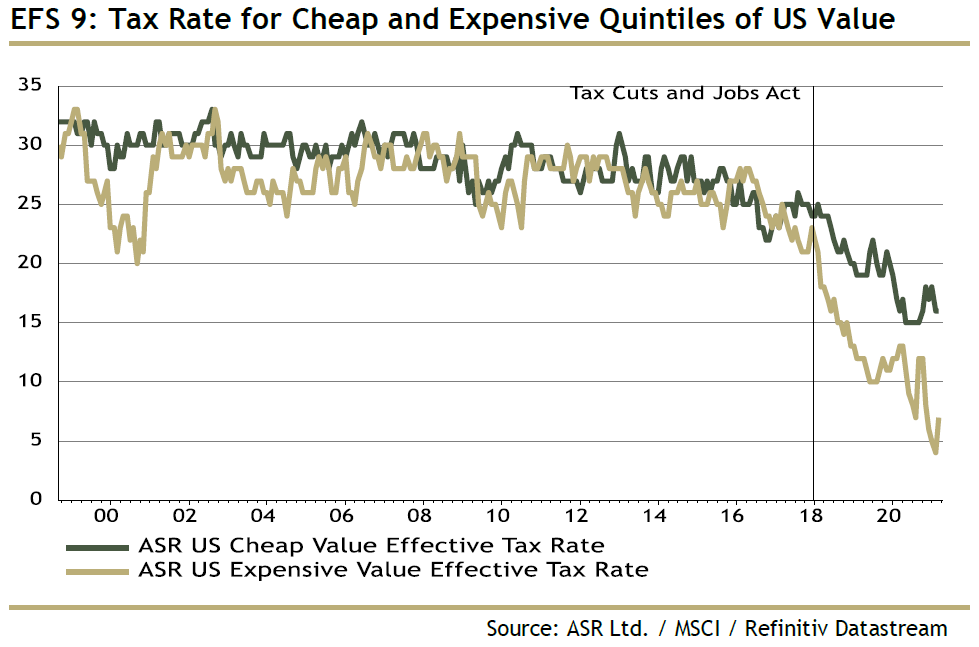

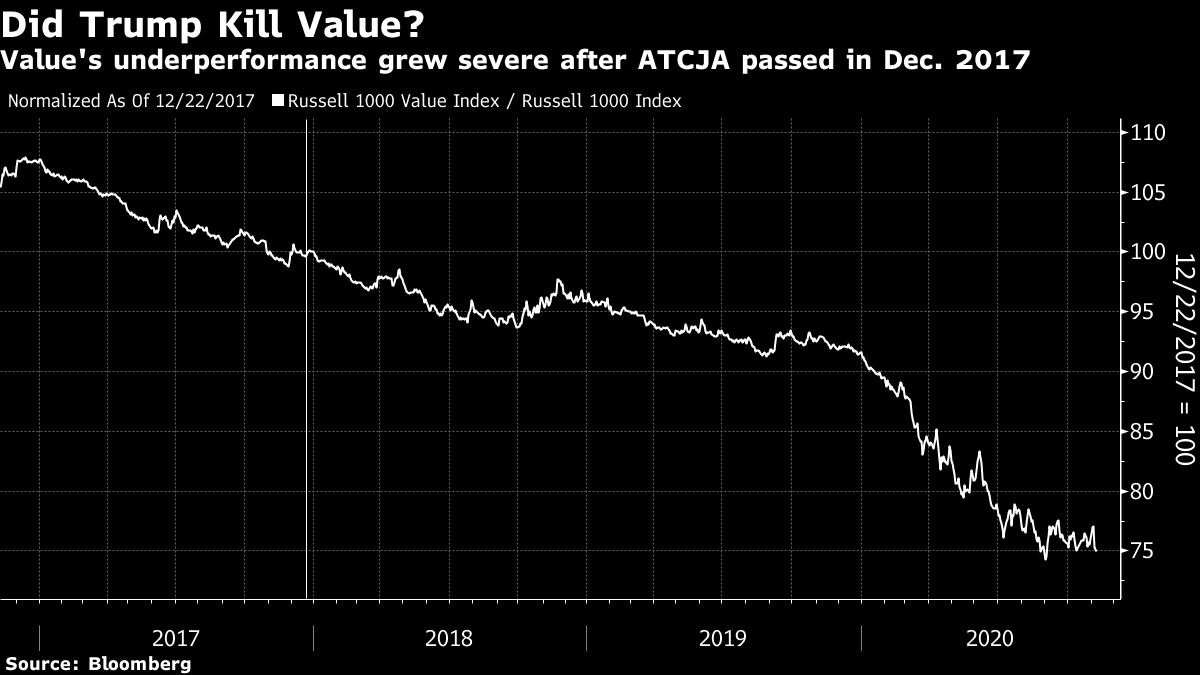

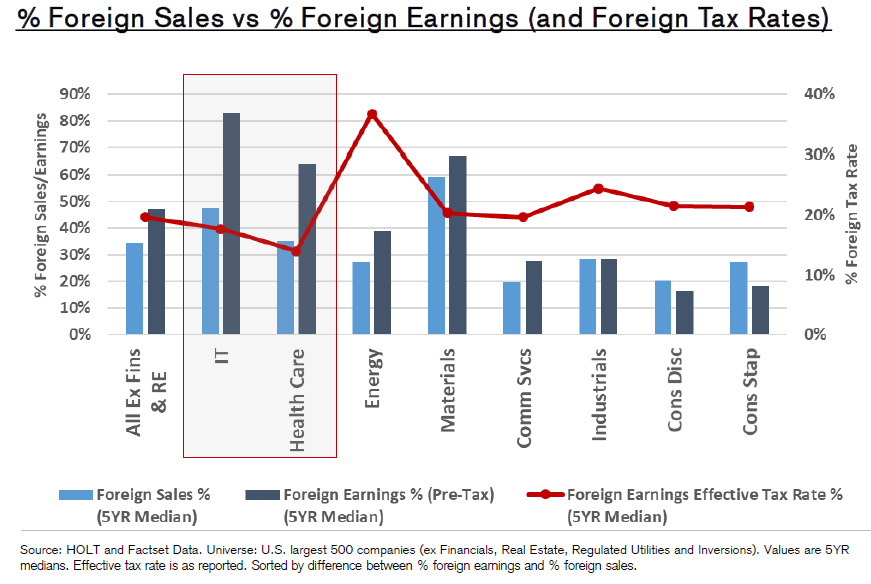

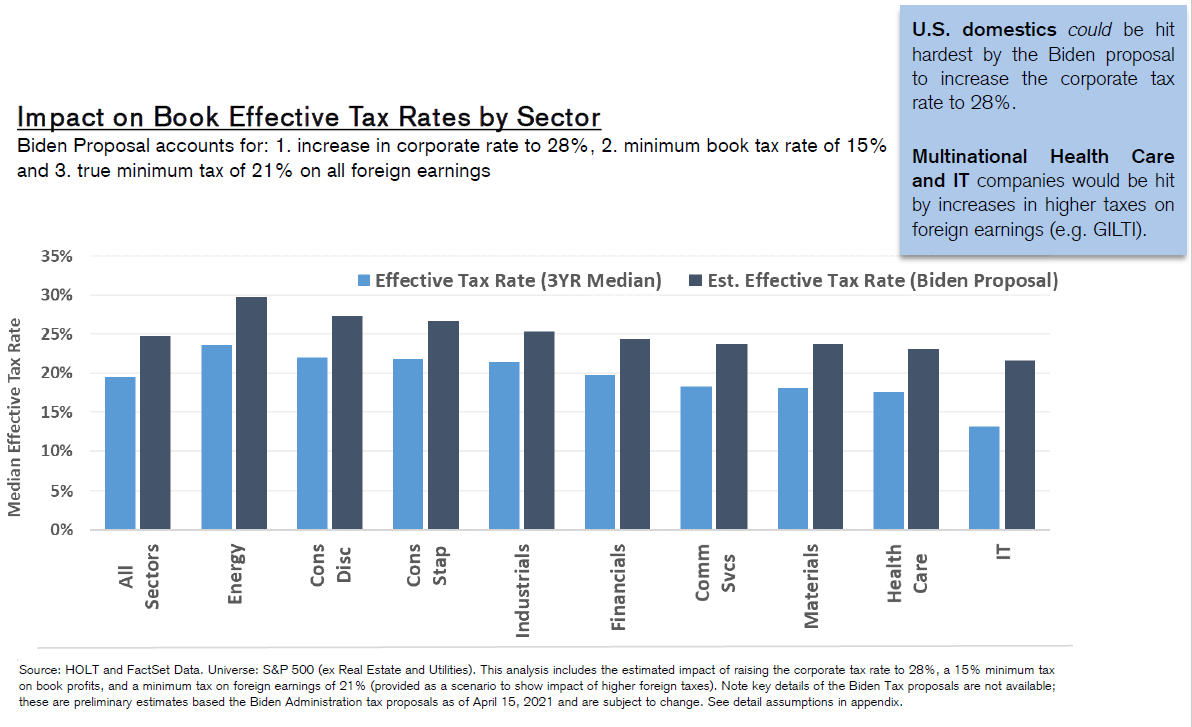

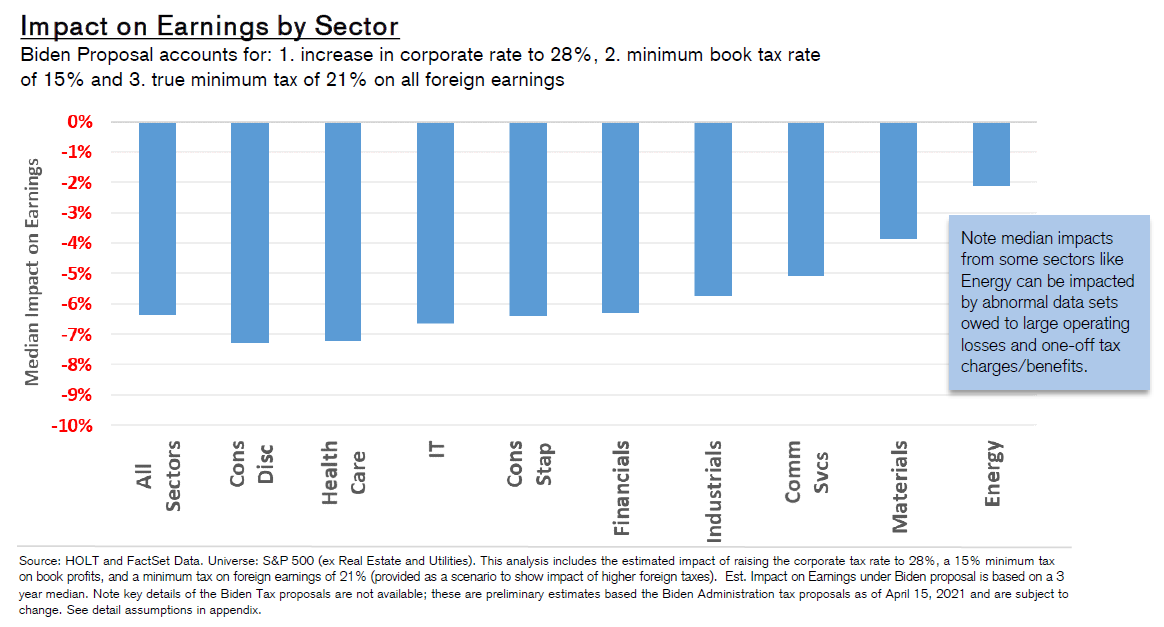

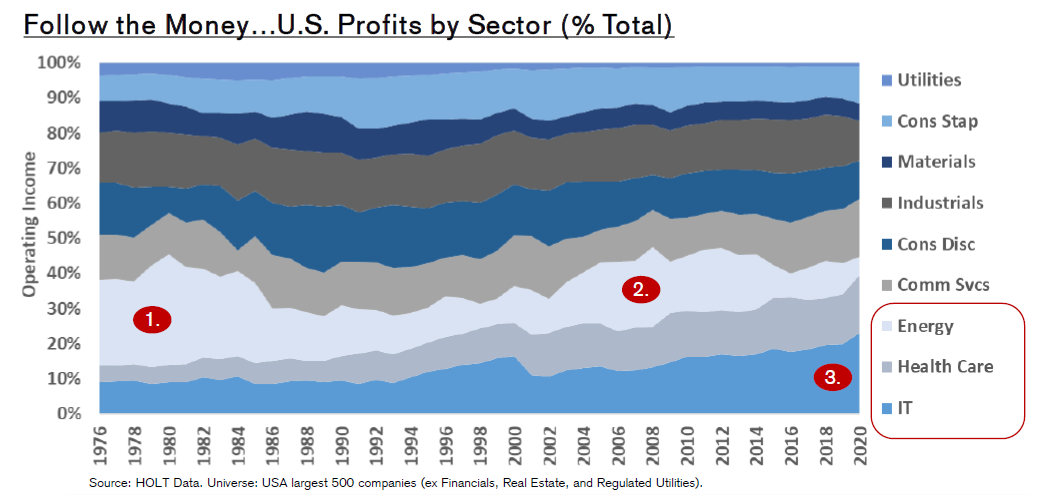

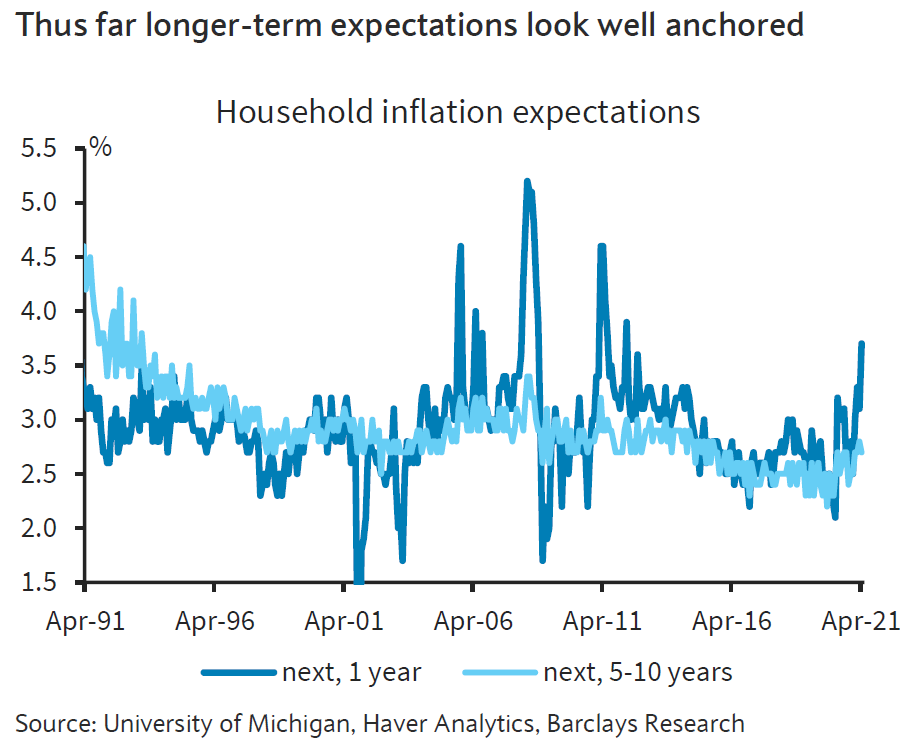

For more, read the administration's "opening bid" in The Made In America Tax Plan. There is more to the issue than a standard presidential negotiation with Congress, as the Biden team is hoping to deal with international taxation issues through a "Global Minimum Tax" deal with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Such an agreement would stop countries from undercutting others, but probably at the cost of raising less tax than the Biden team currently hopes. The parts of this plan that can pass muster with Senator Manchin (who has already made clear that he prefers 25% to 28%) will probably become law. For investors, there isn't much point combing through the proposals as they currently stand. That doesn't mean the issue can be ignored though. Is it priced in? The Trump tax cut, which in hindsight appeared inevitable, only really began to seem plausible in about September 2017, when other early priorities, such as repealing Obamacare, had fallen by the wayside. It didn't pass into law until the week before Christmas. At that point, as this chart from BCA Research showed, estimates for earnings per share for 2018 and 2019 suddenly increased; analysts waited for confirmation before making any changes:  Companies with the highest effective tax rates only began to outperform in a big way once the deal had been done. Logically, these companies stand to do worst from a reversal of the Trump tax cut, but so far, they are outperforming again under Biden:  Despite great interest and speculation, then, it is fair to say that so far any Biden tax changes haven't been priced in at all. As any tax rises would take effect before much of the money they raised could be spent, it is also fair to expect them to have a negative effect on the stock market (and a positive one, at the margin, on bonds). Is there a case for further reform? Years of congressional dealmaking have rendered a complicated tax code that treats companies very unequally. The gap between the effective corporate tax rate and the official statutory tax rate has narrowed, but it still exists. Companies pay less on average than the statutory rate, as illustrated here by Charles Cara of Absolute Strategy Research Ltd. of London:  The range also remains wide, although the number that pay the highest rates has reduced considerably since 2018. The changing patterns of tax rates, as shown in this heat map from Cara, show that any reform is going to have an effect on companies' relative performance:  Meanwhile, there are reasons why higher taxes could be good politics. Corporate tax as a proportion of GDP has fallen steadily, even as profits have increased:  Over a longer time scale, revenues from corporate taxation begin to look shockingly low. They have fallen to barely 1%, from more than 7% after the war. With populism in the air, it shouldn't be difficult to sell some kind of hike:  One further reason for reform is that the tax cut didn't have the hoped-for effect. There was no obvious boom in capital expenditures or research and development. What did happen was a startling rise in buybacks, almost entirely by companies with lowered tax rates.  Given all of these circumstances, it would be surprising if some meaningful tax hike could not be passed. What effect would a tax hike have on factors? It's just possible that President Trump destroyed the value factor, and a reversal of his corporate tax cut could aid a revival. The following chart from Cara of Absolute Strategy shows the effective tax rates paid by the cheapest and most expensive U.S. large-cap stocks. The cheapest saw a much smaller reduction than the most expensive. Over the preceding decade, cheap and expensive stocks paid tax at much the same rate. Judging by this chart, the Trump cut may have had much to do with the subsequent collapse of value stocks:  Correlation doesn't imply causation, but the way effective tax rates parted company just as value started to underperform is mightily suggestive:  A tax hike might just be the catalyst for a value revival. What effect will this have on sectors? More or less any reform that passes will have a bigger negative impact on information technology and healthcare than other sectors. That is because these companies have relatively large foreign profits, and a relatively low effective tax rate on them, as this chart from Credit Suisse Group AG shows:  Credit Suissse also crunched the numbers on the assumption of a hawkish tax hike, in which the rate rose to 28% with a minimum of 15%.Tech would still enjoy the lowest rates, but endure by far the sharpest increase:  Using the same assumptions, consumer discretionary, healthcare and tech companies would take the biggest hit to earnings, while materials and energy would be least affected:  This is ironic, because in the past when energy earnings have boomed, during the oil spikes of the late 1970s and again in 2008, politicians were keen to recommend imposing special taxes on their profits. Now Credit Suisse shows that tech profits look similarly distended, and therefore a similarly tempting political target:  There's no need to get out tax calculators yet, as it's months before any increase can become law. But some effects are already clear. As negotiations continue, expect the issue to gain in importance. Investors don't want to be late, like they were last time. More on InflationThe inflation debate rages on. This is your reminder that I will be discussing the issue with my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Mohamed El-Erian, who also these days runs Queens College, Cambridge, at 1:30 p.m. New York time, at TLIV <GO> on the terminal. Send questions to my colleague Kriti Gupta at kgupta129@bloomberg.net. Before that, one brief observation on the "reflation trade," and a further pearl of wisdom from my interview with Emi Nakamura, an economist who's taken a lead in the empirical study of inflation. Several correspondents pointed out that the retreat from the reflation trade appears to have halted at the first sign of technical resistance. Specifically, the TLT exchange-traded fund, carrying Treasury bonds with maturities of 20 years or longer, bounced off its 50-day moving average; while 10-year yields are again above their 50-day moving average after a brief drop below:   So for the time being, the reflation trade lives on. Should it? I put that question to Nakamura last week. The crucial questions: What causes inflation, and how can we tell when it is coming? Reassuringly, an empirical economist is looking for the same things as the market experts. The Phillips Curve For generations, the Phillips Curve — the notion that lower unemployment might lead to higher inflation — has framed discussions. In a massive study, The Slope of the Phillips Curve: Evidence from U.S. States, published by the National Bureau for Economic Research last year, Nakamura and colleagues Jonathon Hazell, Juan Herreno, and Jon Steinsson looked at state-level data from the 1980s onward. There was almost no relation at all; when one state has a particularly sharp rise in unemployment relative to others, there is no sign that inflation reduces. Paul Volcker and Regime Changes So how did inflation suddenly come under control under Paul Volcker's Federal Reserve in the early 1980s? He presided over a rise in unemployment that was accompanied by a fall in inflation. But the relationship wasn't through the channel of the labor market and reduced pressure for higher wages, but via perceptions of other actors in the economy. "It showed that the Fed was a real institution," said Nakamura. "And it showed that it was bipartisan. Volcker didn't get fired. That was impressive." Clues in the Data On a month-to-month basis, the current market fascination with inflation data makes little sense. In any one month's data, plenty of prices will have moved in the opposite direction to the overall level; the range is wide. And price rises come with a natural lag. Once a product has been distributed and promoted with packaging that often includes the price, its price will be sticky for a while. Such arguments helped to explain why there was no great inflation in toilet paper prices in the early months of the pandemic; stores couldn't raise prices ad hoc to prevent hoarding, despite a classic supply-demand imbalance. That means "look at the core" and how it moves over months. Expectations and Reflexivity What matters most is expectations. Both consumer surveys and bond market breakevens reflect considered judgments on what people expect from future price levels, and the concept of what George Soros calls "reflexivity" is at work. When people expect inflation to be stable, they don't demand higher prices. So look at surveys, and the bond market. So far, the University of Michigan's regular survey shows remarkably well anchored expectations (the chart is from Barclays):  So for inflation to return in full force, the institutions that govern the economy need to convince us all that there has been a regime change. Given the inequitable effects of unemployment and resulting anger, it is quite possible that inflation will be allowed to take off again. What is critical is whether the Fed and other economic institutions really will allow the regime to change when tested by the market. Survival TipsMaybe taking refuge in sport is no longer a good idea. Twelve football clubs plan set up their own European Super League, of which they would be permanent members and which would effectively supplant the Champions League. It's aroused impassioned opposition. The plans also shows up an odd role reversal between the U.S. and Europe. American sports are socialist; baseball is exempt from antitrust laws, and all sports ensure that every club has a similar budget, and that one season's weakest get first choice of new players the next year. European soccer is capitalism red in tooth and claw. Buy a club and you can pour money into it; clubs that lose can drop out of the league and go bankrupt. The joy of European soccer is the American dream that your local team might one day make it all the way to play with the big boys. Fans accept the risk of annihilation. It can be excruciating. This is what happened in 1997 when Brighton (my home town team) visited Hereford on the last day of the season with the clubs occupying the bottom two positions in the league. One of the two would be kicked out. Almost a quarter century later, Hereford have been wound up, and Brighton, who didn't even have their own ground in 1997, are in the Premier League. It probably won't last, but it's been fun. Perhaps the club owners backing this breakaway (including the normally enlightened owners of the Boston Red Sox who also own Liverpool) should grasp that what fans want most is to be able to dream. The super league would take that away. Nobody wants to be from hope and fear set free. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment