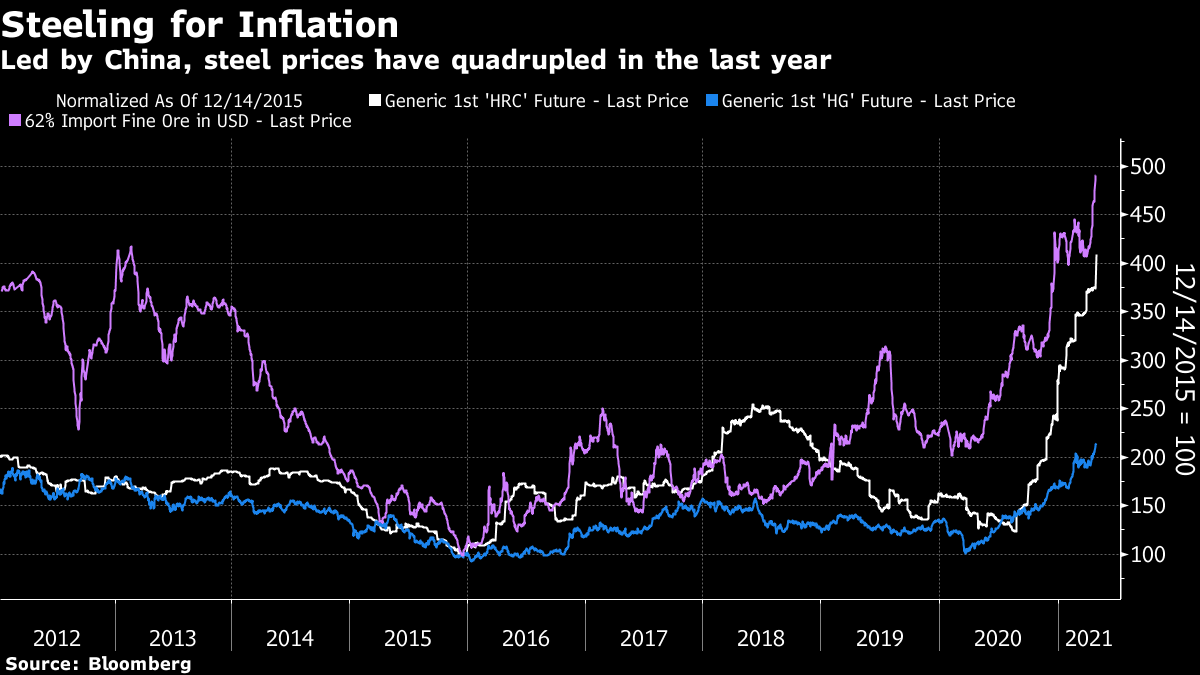

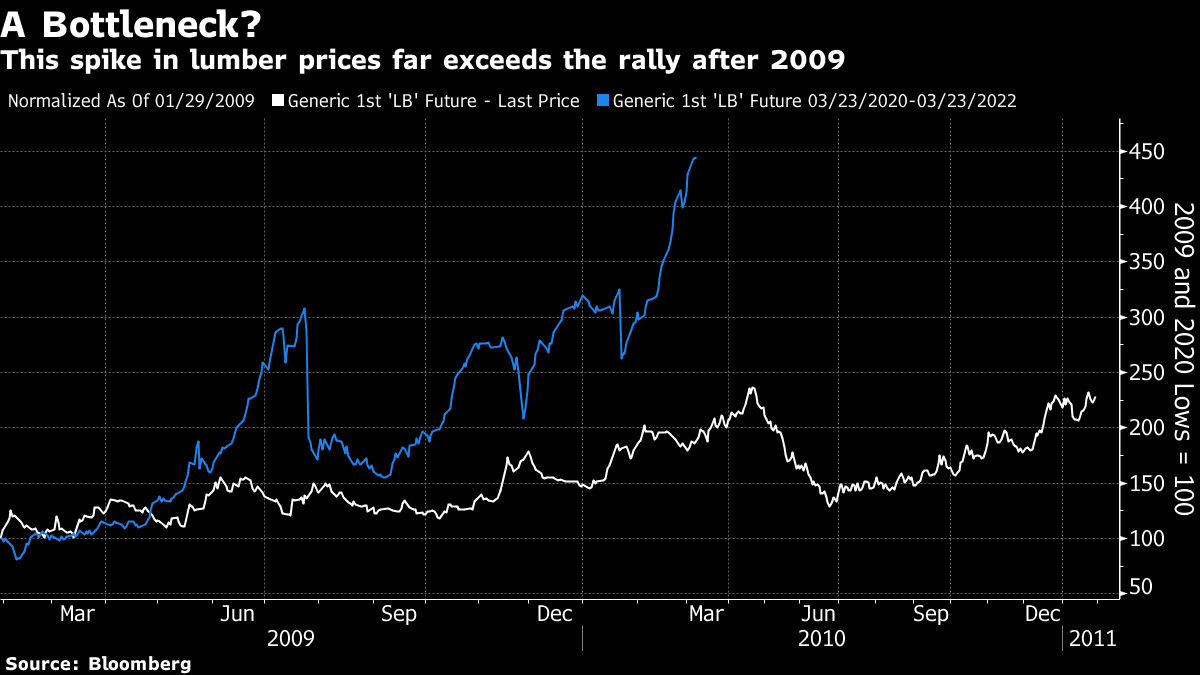

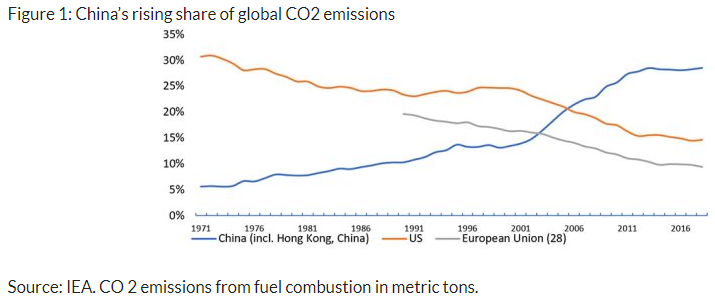

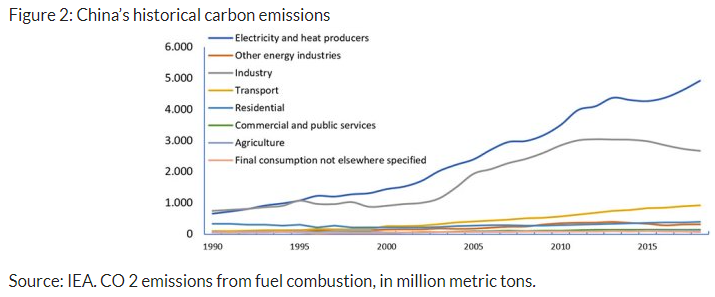

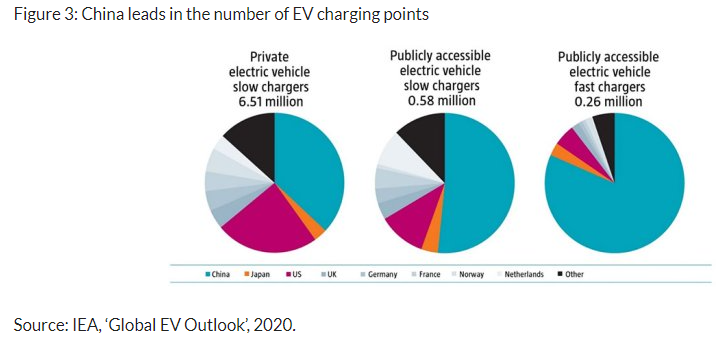

Tales of the ExpectedJerome Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve, endured his latest joust with the journalistic profession, and did his best to say nothing interesting. He largely succeeded. But the latest Federal Open Market Committee meeting still left us with a few more clues on how the Fed intends to navigate through an exceptionally dangerous environment. No changes of any kind were made to monetary policy. Rates stay on the floor, and the central bank will continue buying assets as fast as before. But its statement did acknowledge that the economy is strengthening. The Fed had no choice; failure to do this would have made the governors look silly. It also acknowledged the progress that the U.S. is making in the battle against the pandemic. This is significant because the FOMC has made vanquishing the virus a condition for removing its support for the market. This then was a tacit admission that the moment to start the phased withdrawal is coming a little closer. But everyone could work out that things had gone better than it had been fair to expect at the end of last year. As all of this was about as predictable as possible, markets did little more than twitch. Stocks closed slightly lower, bond yields reduced a little, and the dollar gave up some ground. What mattered was Powell's guidance on what it will take for the Fed to start its retreat — which involves first talking about tapering asset purchases, then actually tapering, and then raising target rates. The excellent data of the last few months, he insisted, weren't good enough to prompt such talk. The FOMC needs "substantial further progress" for that. "We got a nice jobs report. It's not close to substantial progress. We've had one great report. It's not enough. We're just going to need to see more data. It's as simple as that." This was a tad disingenuous. Virtually every data release for the last month has suggested a very strong recovery. The Fed wants great improvement in unemployment, which is still running at a 6% rate, compared to 3.5% before the pandemic. But Powell insisted that the Fed is conscious of the history of the 1960s and 1970s, when the economy succumbed to an inflationary spiral. The criterion to start tightening policy before unemployment has reached desired levels will hinge on inflationary expectations. "If inflation moved above 2% and threatened to move longer-term expectations materially above 2%, we would move." So far, inflation remains "transitory" (to use the Fed's key word), because it has been driven by low base effects from last year (unquestionably true) and "bottlenecks" in supply caused by the pandemic shock. So there are two questions. Do we see any signs of rising prices caused by anything more than a transitory bottleneck? And, are inflation expectations showing signs of settling "materially above 2%"? Bottlenecks?If there is any clear sign of a possible bottleneck, it is in the industrial metals market. Steel and copper prices, in particular, have shot up. The following chart shows generic futures contracts for copper (HG) and steel coils (HPC), along with the main Qingdao contract for steel in China. The metals are in the grips of a classic cycle, when demand rises just as supply has been limited. Copper has more than doubled since last year's bottom, but is dwarfed by the massive increases in steel prices. China tends to lead the cycle. The chart is normalized for the point in December 2015 when steel prices hit bottom before China embarked on a new credit expansion:  Judging by the behavior of steel producer stocks, which have more than trebled since the bottom last year, equity investors have enough of an inflationary psychology to assume that prices will keep rising:  Can moves like this really be dismissed as a "transitory" response to supply constraints? Surprisingly, they just might be. The rally in copper prices from the nadir of the global financial crisis in early 2009 was impressive but proved short-lived. Copper peaked in 2011, and then entered a long bear market. So far, as the next chart shows, this rally is slightly behind the pace of that one:  The rise in another basic commodity, lumber, is a little harder to view as temporary. Rising house prices have driven demand far beyond what wood mills can supply at this point. The same thing happened during the recovery of 2009. But this time, the rally is on quite a different scale:  The Fed can still just about protest that the gains in material prices (which also include huge rises in basic food prices) are transitory. If the commodity rally continues like this for much longer, that will become an increasingly difficult position to sustain. Great Expectations Markets give us nice and precise measures of inflation expectations, via the breakevens between inflation-protected bonds, or TIPS, and conventional fixed-income Treasuries. The prediction this generates for average inflation over the next five years is just under 2.5%, which is a level not seen since the oil spike prompted a brief scare ahead of the crisis in the summer of 2008. Five-year expectations have been at this level for a week, but didn't set a new high after Powell's speech. They still look close to fulfilling his criterion of a level materially above 2%. If this were to rise to 3%, or consolidate where it is now for a few months, that would begin to pile pressure on the Fed:  Ten-year expectations are slightly lower, and hit a new Covid-era high on Wednesday afternoon. They are now at their highest since early 2013, a point that also saw gold drop into a long bear market as investors began to realize quantitative easing hadn't created inflation. As 10-year expectations have been higher than this in the post-GFC era without prompting a return of inflationary psychology, Powell is entitled to argue that this isn't yet "materially" higher than 2%. But the direction of travel is clear. Further rises will make it harder for the Fed to ignore.  The best measure to justify continued lenience is the so-called 5-year, 5-year breakeven, which captures an implicit forecast for a five-year period starting five years hence — in other words from 2026 to 2031. In the past, Fed chairs have put a lot of emphasis on this measure. It remains lower than the 2021-2026 prediction, suggesting the market is positioned for a rise in inflation that is then successfully headed off by the Fed. The 5-year, 5-year hit a Covid-era high on Wednesday, but was this elevated as recently as 2014, and above 3% several times in the first five years after the GFC. This looks like good evidence that investors still don't see much chance of the Fed repeating the errors of the 1970s:  So, it looks as though Powell can claim with a straight face that expectations don't require the Fed to act. If commodity prices or breakevens rise much further, that could soon get very hard to sustain. ESG Opportunities in China...Earlier this week, I wrote about the contradictory impulses for ESG investment in China. The country has a remarkably carbon-intensive economy, but plans to move to a cleaner model. Pollution is dreadful, but the political need to address this is pressing. So does this make looking for ESG opportunities in China a good or bad idea? Robeco argues that China is indeed a good destination. In the process, the fund manager also implicitly suggests that Tesla Inc.'s position in electric vehicles isn't as assured as its backers think. China's record in carbon dioxide emissions is far worse than the U.S. or the European Union:  Breaking down by sector, Robeco shows that industry's emissions peaked a few years ago, and have declined since slightly. The biggest problems are in electricity and heat production (by far the most serious), and transport. So investment in clean-power technologies looks a good bet, according to Robeco, with the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy expected to reach 25% by 2030, compared with an earlier target of 20%:  More intriguing is electric vehicles. China is far ahead of everyone else, including the U.S., in investment in infrastructure needed to make EVs a practical option. So EV growth looks a safe bet:  What does this mean for competitors in the U.S., led by Tesla? Potentially very bad things. It's no surprise when value investors criticize Tesla, which isn't cheap. When growth investors inveigh against the company, that's much more serious. The following comment comes from Louis Navellier, an industry doyen. You can read up on his growth philosophy in The Little Book That Makes You Rich. When an investor like Navellier says something like this, Tesla needs to take notice: The sad truth of the matter is the EV revolution is now being led by China and Europe where sales and government EV tax incentives are much stronger. At last week's Shanghai Motor Show, VW Group was introducing exciting new EV models (e.g, A6 e-tron), while Tesla was noted for a disgruntled Tesla owner jumping on the roof of a Tesla shooting "brake failure," which was also printed on her t-shirt...

For Tesla to get its mojo back, the company has to get ahead of the EV media cycle... Tesla's reputation may have also been hurt by Elon Musk bragging about buying Bitcoin and then quietly selling 10% of its $1.5 million investment for a $101 million quick profit... Furthermore, appearing on Saturday Night Live (SNL) this weekend is also raising some questions about Elon Musk, who appears to be increasingly obsessed with his fame in possibly an unhealthy way. Hopefully, for Tesla's sake, Musk can have a successful SNL appearance, rebuild his reputation and refocus on introducing innovative vehicles as well as efficient manufacturing plants in the upcoming months.

He isn't the only one to find Musk's decision to host SNL disturbing. Peter Atwater, who monitors behavioral and cultural trends for Financial Insyghts, has a similar opinion. "The culturization of today's extreme financial fads is a warning sign that the top is near," he warns. "Mr. Musk's upcoming stint on SNL all but confirms that." Survival TipsThis tip is also a profound thank you. Some 30 years ago, Samuel G. Freedman started teaching a class at Columbia Journalism School that became known as the book-writing seminar. His sole object was to get all participants to the point where they had a book proposal and sample chapter sent to a literary agent. His only criterion for success was the number of contracts that resulted. Earlier this month, he posted the news that his students have now landed the seminar's 100th book contract, with 76 published to date. Another 500 or so students didn't get a contract but still had a life-changing experience. It's difficult to teach someone how to write a book from scratch. It requires total commitment and a lot of discipline. Sam's approach was remarkable. He worked everyone unbelievably hard, expecting thousands of words of prose each week. As part of the deal, he then edited each submission within an inch of its life. You can get people to work hard for you if you work hard for them. He also made it clear that writing narrative non-fiction could be distilled into the basics of craft. Get the fundamental disciplines right, and then maybe the students would find they could give their genius free rein. Early lessons included looking at early Picassos, showing how he mastered all the skills of classic draftsmanship, and proved himself capable of being a great conventional artist, before ripping up those conventions. Another involved listening to John Coltrane's My Favorite Things as he rammed home that Coltrane was obsessive about playing his scales every day. The brilliant extemporization was only possible because he practiced every day until his lips were ready to bleed. It worked. I took the class 21 years ago, and you can find the book that resulted here (sadly, you can pick it up very cheaply these days). Writing it was an other-worldly experience, and the lessons have become permanent parts of my life. So, set ambitious and tangible goals; always concentrate on craft; practice, practice, practice; and get people to work hard for you by working hard for them. That, I think, was the formula. We could all probably learn from it, even if we don't burn with a desire to write a book. Thank you Sam, and congratulations. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment