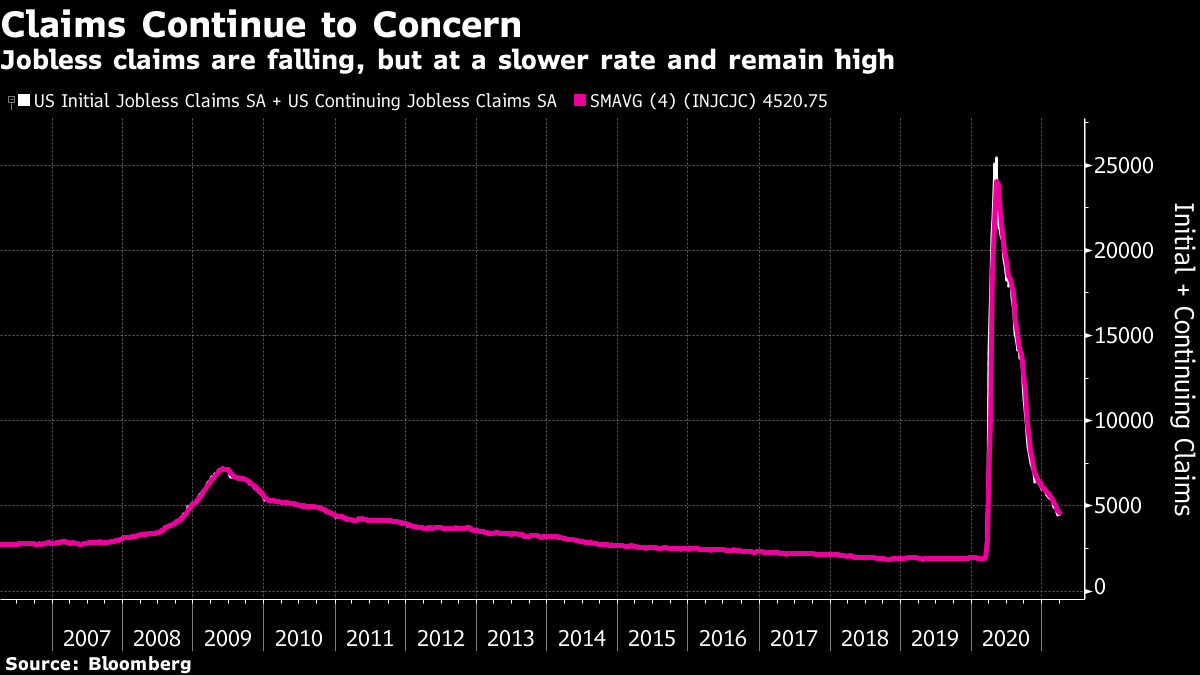

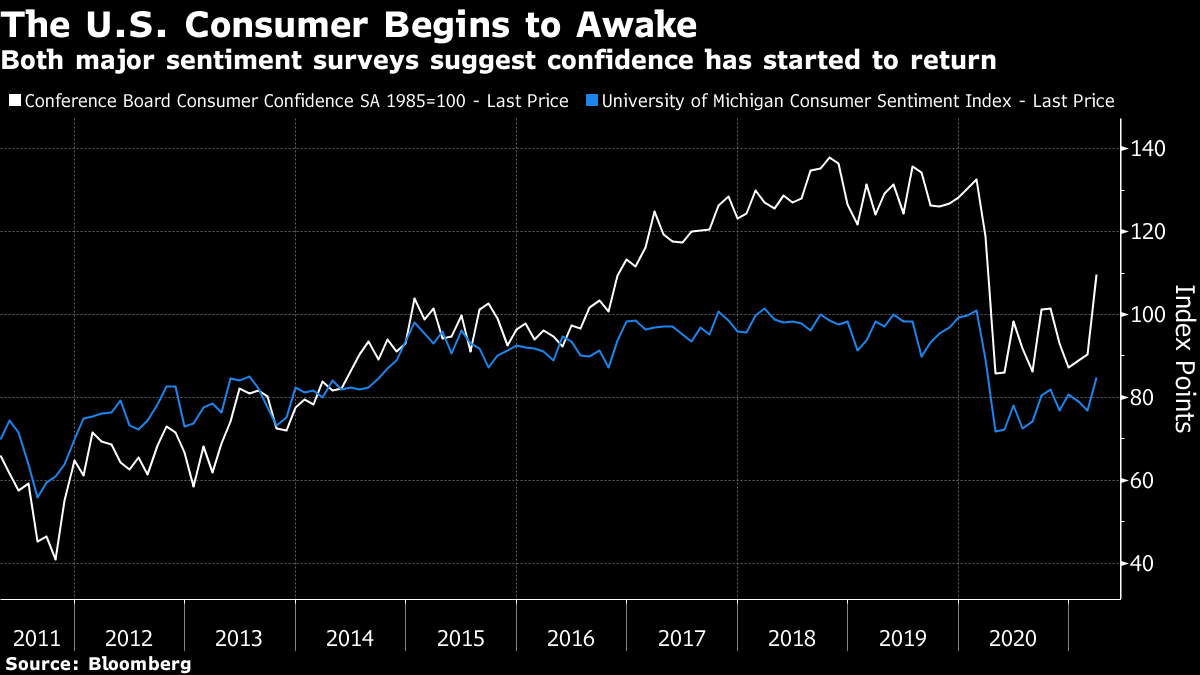

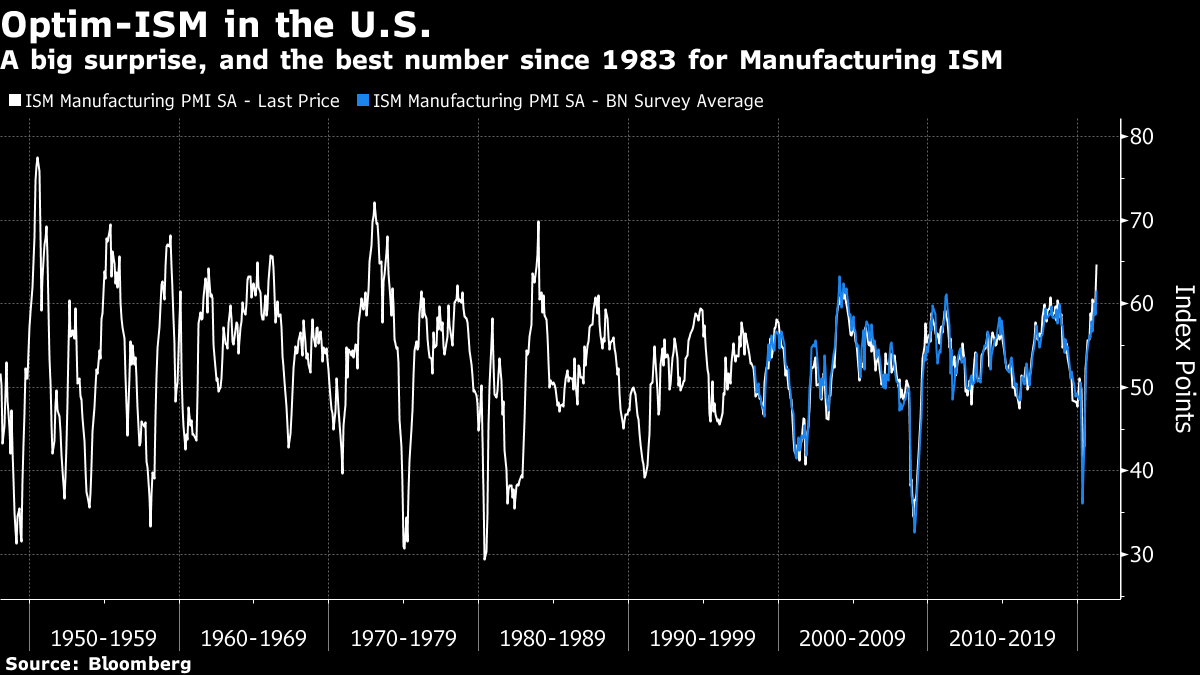

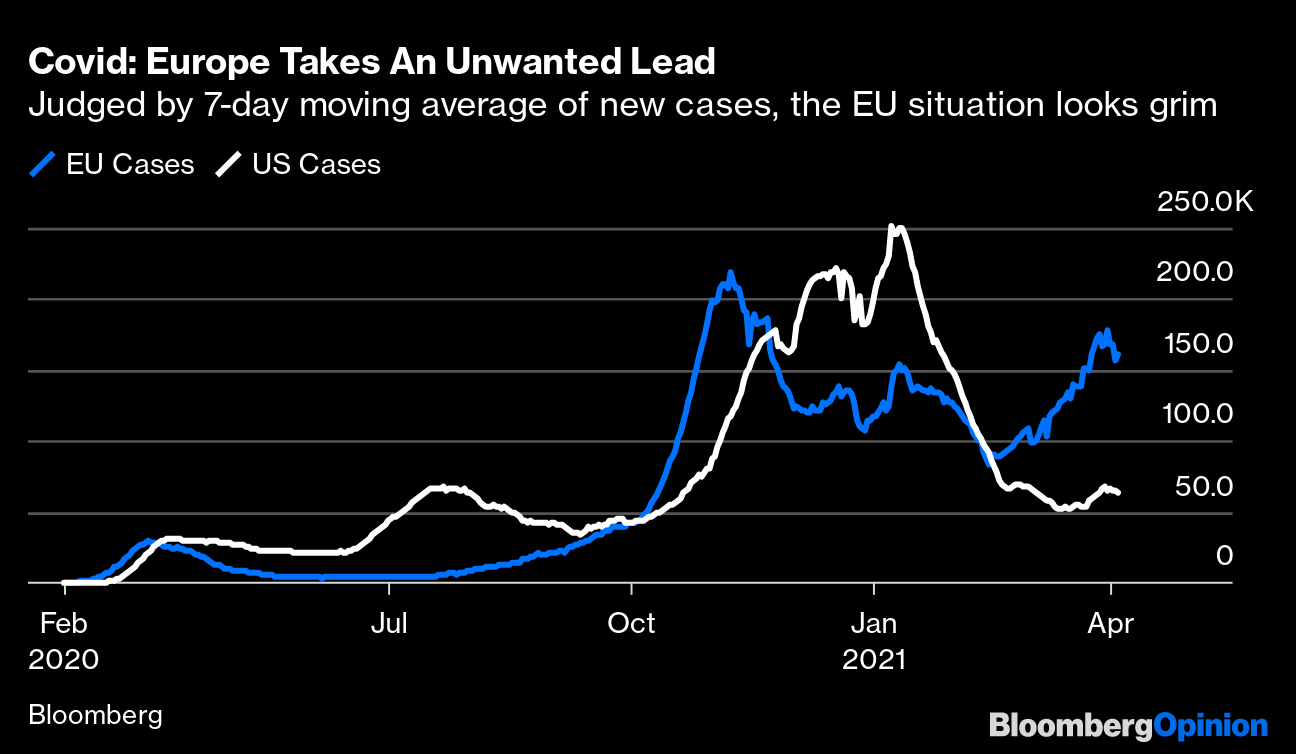

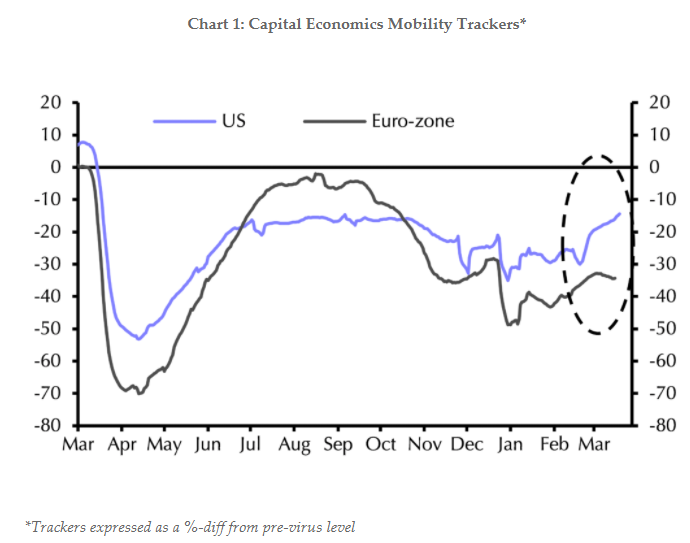

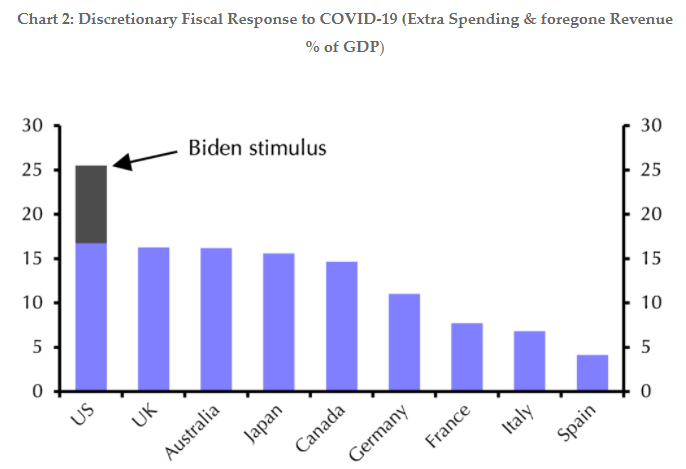

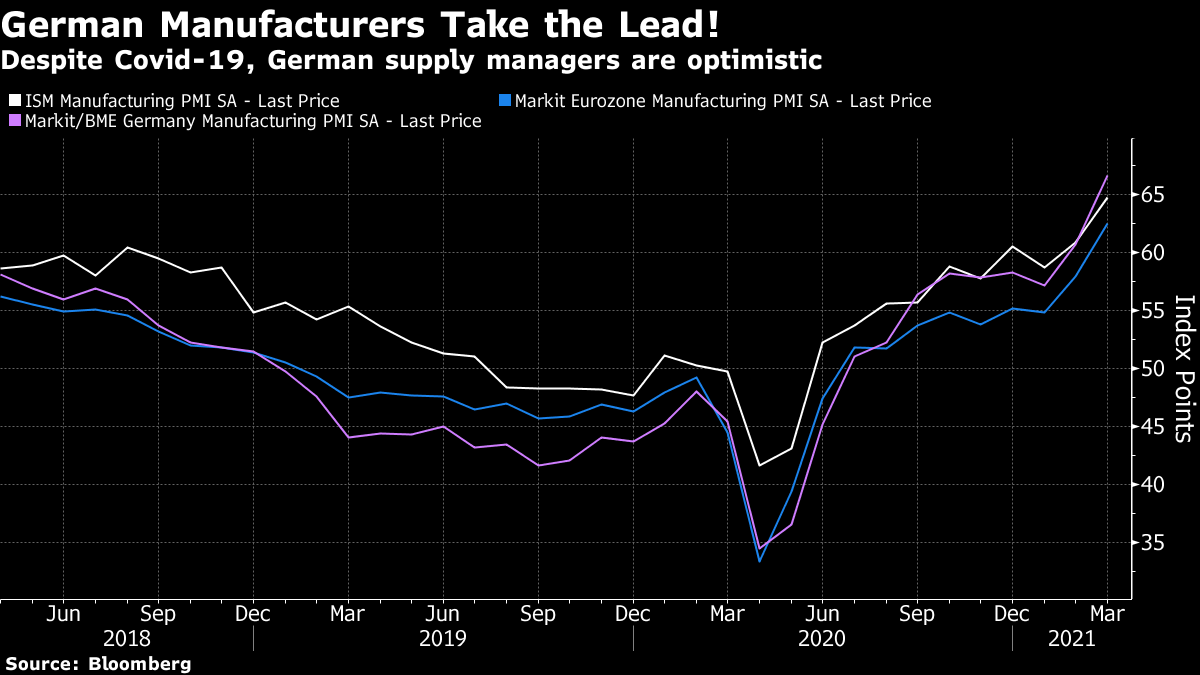

Too Much of a Good Thing?If the U.S. has a problem at present, it could be too much of a good thing. The economic rebound from last year's seizure is proceeding with remarkable speed, and financial markets are cheerfully moving to price a continuing recovery as a reality. As I wrote last week, the first quarter was the worst for bonds in four decades. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 ended April 1 above 4,000 for the first time in history, after a quarterly gain of just over 7%. And the dollar strengthened. So markets are plainly keeping up with this fast unfolding recovery. Here are the highlights. Last week brought news that combined continuing and initial unemployment insurance claims were down again. They remain disconcertingly high, showing that economic pain persists; but the speed of the recovery is almost as exceptional as that of the crash that preceded it:  Friday's unemployment data surprised to the upside. Looking back to the 1970s, the speed and severity of last year's recession appear almost off the charts, but then the same is true of the recovery. At 6%, the unemployment rate as conventionally measured is still too high and policymakers doubtless want to reduce it further. But this has been an economic cycle like no other:  We can take consumer sentiment data as showing some degree of confirmation for the jobless numbers. Until now, consumer confidence had badly lagged behind other indicators, barely showing any recovery. The consumer remains much less confident than the average trader in financial markets; still, both the most closely watched surveys now show a clear improvement from the bottom. Whether driven by the vaccine rollout, or by tangible improvement in jobs, this must raise the chances that consumers will spend the large wads of cash they have in hand later this year:  Manufacturing, meanwhile, hasn't been as confident as this in almost four decades. The following chart shows ISM manufacturing data, where any measure above 50 indicates expansion while any number below suggests a recession, going back to 1950. Consensus forecasts compiled by Bloomberg are also included over the period for which we have them. This month's survey was truly extraordinary; supply managers are very optimistic, and far more so than economists and analysts had expected. Looking back through history, numbers like this were common in the 1950s and 1960s, when economic cycles tended to be shorter and more pronounced. It is almost as though the pandemic suddenly returned us to the world that existed back then, when the dollar still had a tie to gold, and when steady demographic growth helped ensure economic expansion. An environment like this is so different from anything that those active in markets today have personally experienced in their professional lives that there is a serious risk of errors. We're just not used to sharp cycles like this anymore:  It would be absurd to call any of this bad news. The last few months have gone about as well for humanity as could reasonably have been hoped — at least in the U.S. But now, amazingly, the question of overheating arises. The Federal Reserve damaged its credibility with a U-turn over shrinking its balance sheet after the equity selloff at the end of 2018; it doesn't want to retreat from its promises of extended dovishness now. But that raises the risk of letting inflation or, particularly, asset prices get out of control. The ISM surveys cover the costs that businesses are paying, and this measure eased very slightly in the latest report. But it still remains higher than at any time since the runaway spike in oil prices in the summer of 2008. Only 0.5% of respondents said prices were falling; all others said they were constant or rising. Concerns about cost-push inflation are reasonable:  Most crucially, there is the risk of global imbalances. This is driven in particular by the pandemic. The European Union has suffered well-publicized difficulties getting vaccines into arms, and been unable to stop a third wave of the virus, which has forced several of the region's biggest economies to reimpose lockdowns. For the first time, new cases in the EU are significantly higher than in the U.S. To be clear, there is still reason for concern about the U.S., where new cases have ticked up in the last week despite the availability of vaccines, while the last few days have seen a slight downturn in the EU:  The third wave has an economic impact, and European economic activity has begun to decline again, as the U.S. economy reopens further:  That difference is likely to widen given that the U.S. is now beginning to enjoy another huge dose of fiscal stimulus from Covid relief measures. This takes the U.S. fiscal response far ahead of that in Europe. Note that the latest plan to spend more than $2 trillion on various forms of infrastructure, which can be expected to stimulate the U.S. economy further in future, isn't included:  The bottom line remains that the great risk is of much stronger growth in the U.S. than in Europe. There are potential serious long-term consequences for the global economy. To quote Neil Shearing, chief economist of Capital Economics Ltd.: We have generally taken a more sanguine view than most about the long-term damage caused by the pandemic. Indeed, unlike in the global financial crisis, we expect most economies to eventually return to their pre-crisis paths of output... But the longer the recovery takes, the greater the risk of economic scarring as investment is permanently lost and skills start to atrophy. If the pandemic leaves a legacy of permanently lower output anywhere, there's a good chance it will be in the euro-zone.

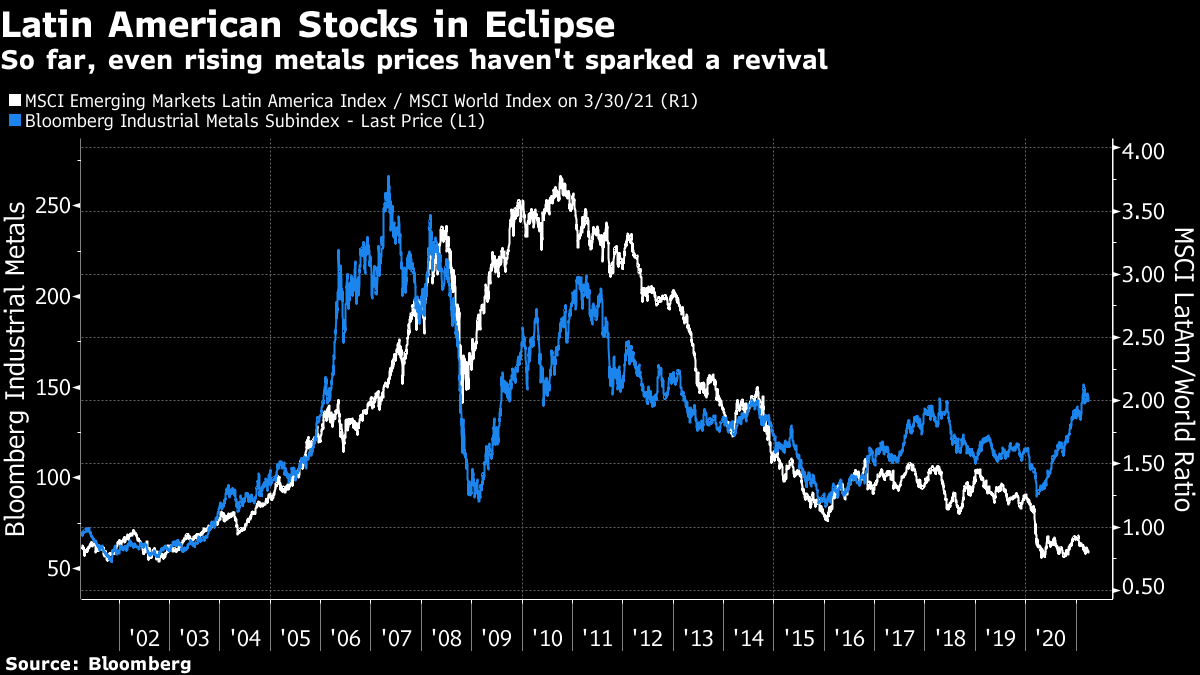

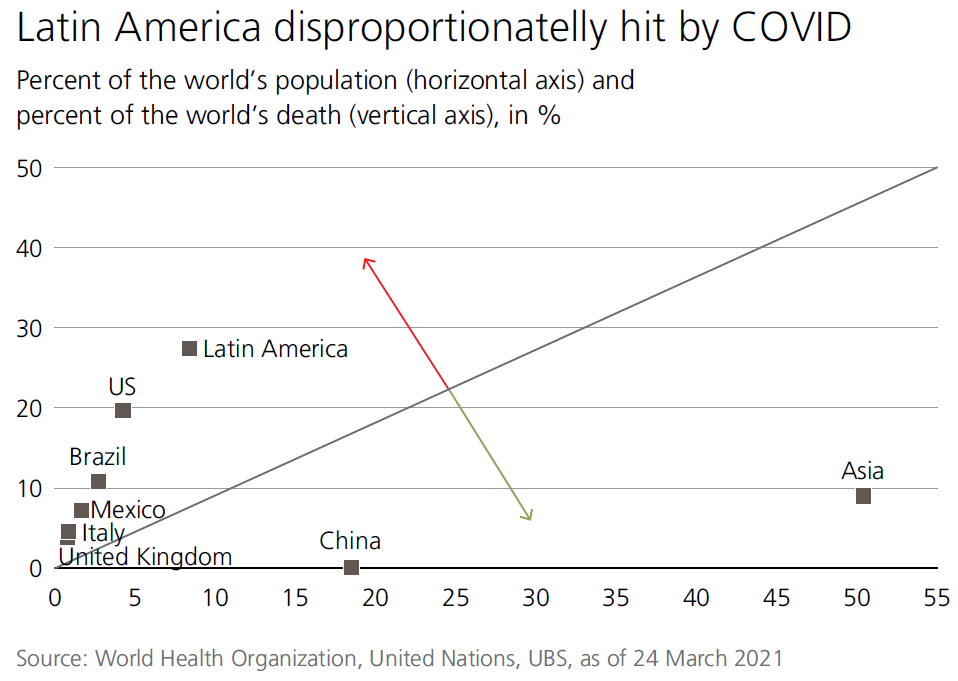

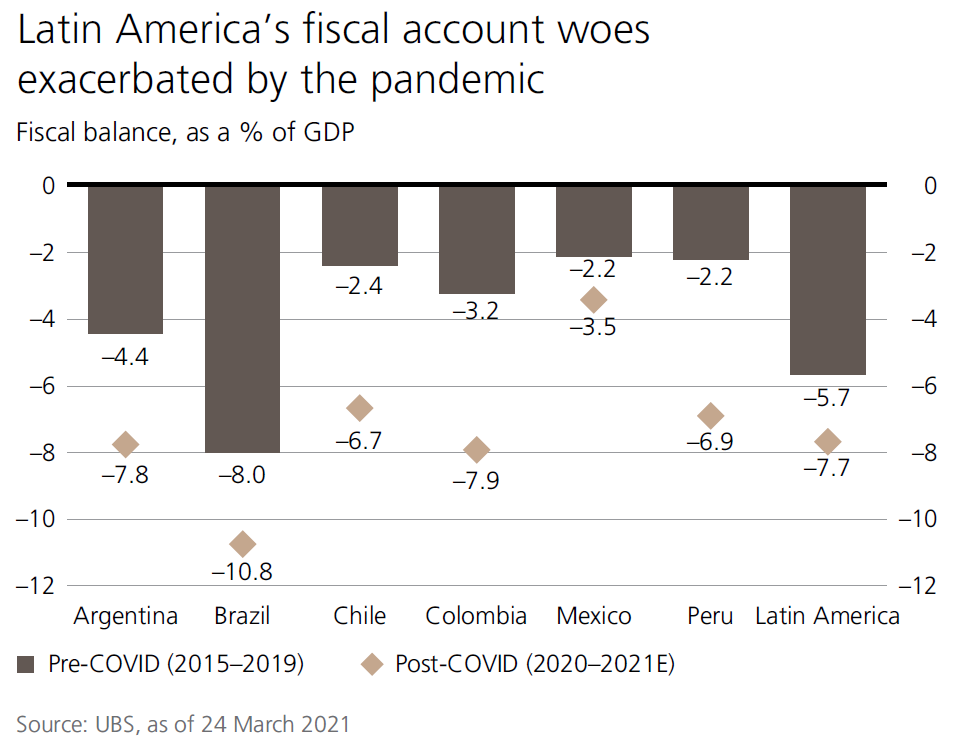

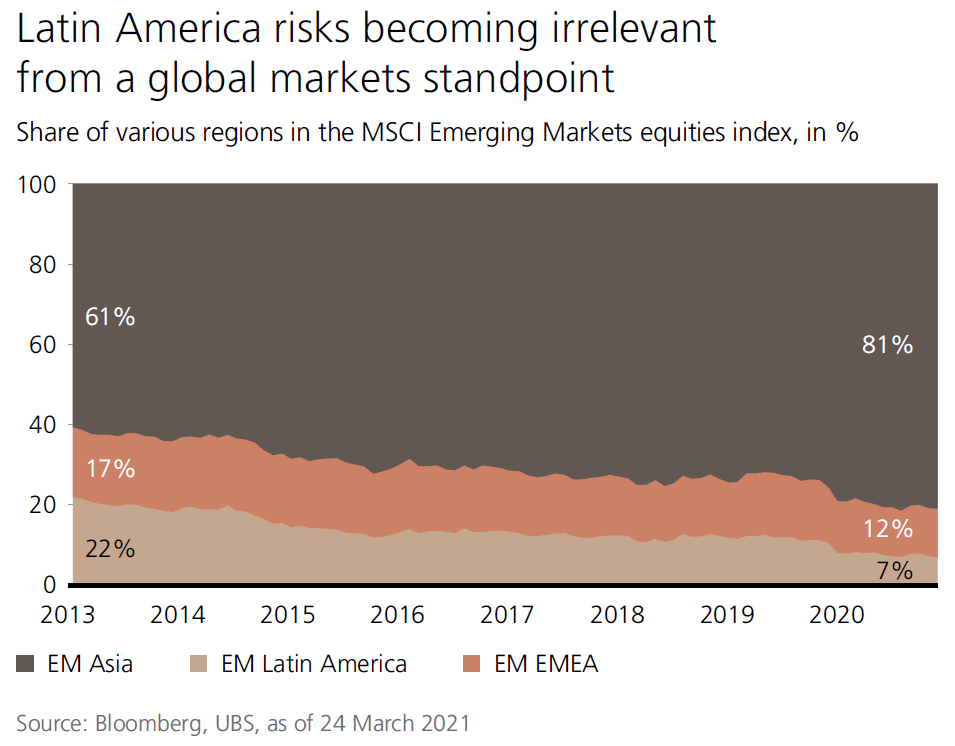

This could feed into the great financial balancing mechanism; as the dollar benefits from inflows caused by European investors buying Treasury bonds for their superior yield, so the stronger U.S. currency helps to contain American inflation (by reducing import prices). These flows also create extra demand for U.S. bonds and avert a damaging spike in yields. Meanwhile, a cheaper euro helps European competitiveness. Or, alternatively, Europe's weakness dampens U.S. exports, even as the flows into the U.S. inflate a bubble in financial assets there. Inflation risks put investors off U.S. bonds even at ever more attractive yields, and the American stock market is reined in. That could also happen. A substantial school argues that worries over Europe are overdone. Its vaccine supply issue should be resolved during the second quarter. If the EU can improve its record on this front, it could soon make up much of the gap. European manufacturers, many of whom export to China or the U.S., seem very positive. This chart compares ISM manufacturing measures in the EU as a whole, Germany, and the U.S. Somehow, the position for German manufacturers seems even more positive than for the U.S.:  Where does that leave us? For the next three months, the pandemic continues to matter more than anything else. The greatest concerns are inflationary pressure in the U.S., and the EU vaccination program. The next few months will be dominated by the search for proof that the U.S. can avoid overheating , and the EU can get its vaccination program on track. El Dorado No MoreMeanwhile, one imbalance gets ever deeper. That is the gap between the north and south of the Americas. Latin America has endured another lost decade. It should be ready to enjoy a periodic boom, but the pandemic may stand in the way. At this point, it looks worrying. Latin American equities' performance compared to the rest of the world tends to be driven by metals prices. In the first decade of this century, the region functioned as one giant play on Chinese growth, as Asia's largest economy demanded more and more from South American mines. But the latest revival in industrial metals prices has overlapped with another downturn for Latin American equities:  Why is this? In a word, Covid. The following chart from Alejo Czerwonko of UBS Group AG shows what has happened neatly. Latin America's death toll is far out of proportion with its share of the global population. Its problems, hampered by crime and poor governance, show no signs of going away:  The pandemic has had a horrible effect on the region's finances, with budget deficits sharply deteriorating. Mexico is a significant exception, but much of the rest of Latin America finds itself in a fiscal hole. This makes it harder to attract the international capital it needs:  It has also become more difficult to attract equity capital, because the region has a dwindling share of emerging market capitalization. That is a problem when flows are dominated by passive investment vehicles. At the turn of this century, Mexico briefly had the largest weight in the MSCI Emerging Markets index, and soon after that investment in Brazil boomed thanks to the vogue for BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) investment. Now, "emerging markets" are effectively Asian. As Czerwonko's chart, Latin America now only accounts for 7% of the MSCI gauge, while Asia is 81%.  Against this background, the region enters a wave of elections. Peru has presidential polls next weekend, as does Ecuador. Both have had very turbulent politics in recent years. Chile has regional and gubernatorial votes next weekend, with presidential elections to follow. The country had been an island of political calm until street protests triggered a constitutional crisis in 2019. In all cases, investors would prefer countries to resist the temptation of going with populist leaders. In July, Mexico has mid-term congressional elections that could conceivably trim the power of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who hasn't been the wildly irresponsible left-winger that many international observers feared — but who has also failed so far to come up with ideas to deal with the country's long-running problems. Contrarians may be excited. Almost 20 years ago, the arrival of an avowed leftist, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, as president of Brazil proved the catalyst for a remarkable rally. After a decade of crises and turmoil, the region was ready to rebound. That might happen again. Middle classes have grown in the last two decades, and anyone willing to do the hard work of looking for bargains on the ground may find them. But as it stands, Latin America has been the greatest financial and economic victim of the pandemic, and there is a risk that the damage could be lasting. Survival TipsWith spring comes a step up in the sports calendar. England's football season is nearing its finale, while baseball has just begun its 162-game odyssey. There is much joy, and reassurance, to be had from the natural rhythms and cadences of sport. In my case, hope and joy has already been dashed as the Boston Red Sox contrived to lose all three of their opening games, at home, to the supposedly terrible Baltimore Orioles. Meanwhile Brighton & Hove Albion, my home town soccer team, had the lead over Manchester United and seemed destined for their first ever win at Old Trafford, before losing 2-1. So much for solace in sports. However, there is always joy to be found somewhere. The weekend brought a "buzzer-beater" for the ages in the final four of the U.S. college basketball championship, a glorious ritual for the country known as March Madness. You needn't know the rules to enjoy it. Sport has the potential to produce moments of delirium out of nowhere. You cannot know that they are coming, and that is precisely their joy. So with that, I direct you to the greatest commentary call of all time, which described how Dennis Bergkamp of Holland scored the goal that beat Argentina in the dying moments of the World Cup quarter-final in 1998. It will bring a smile to any face. It's in Dutch, and that doesn't matter. You'll understand. I hope it helps get your week off to a good start. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment