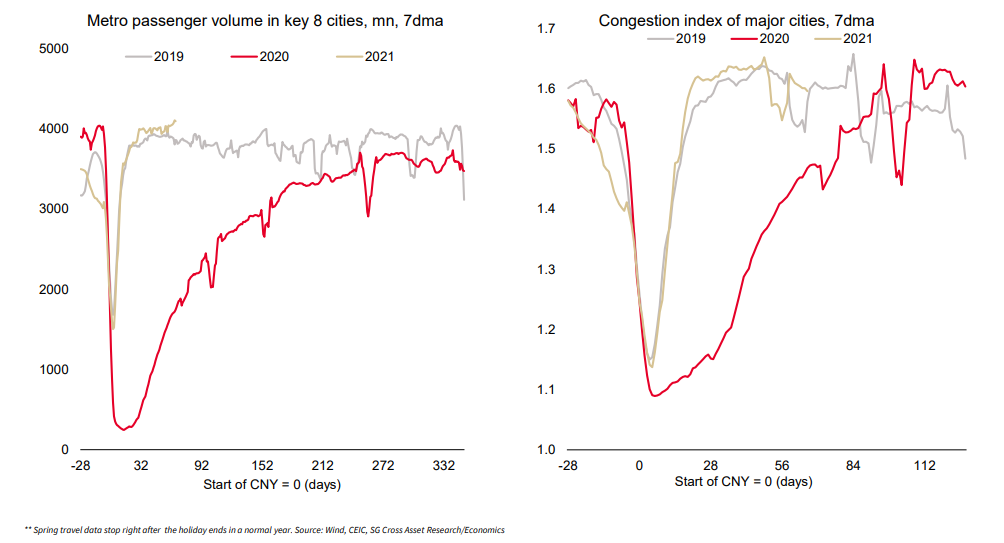

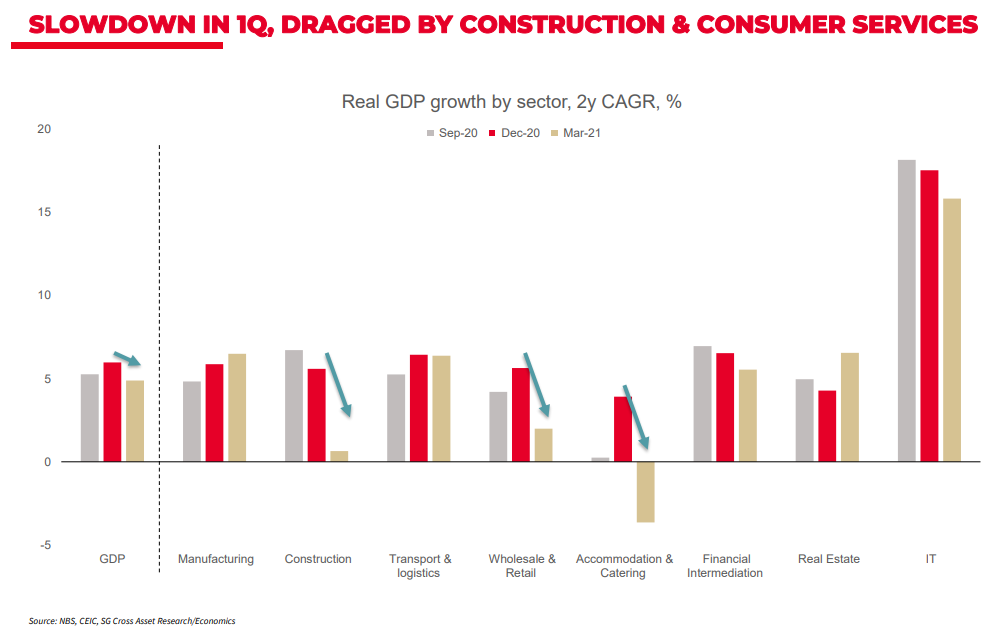

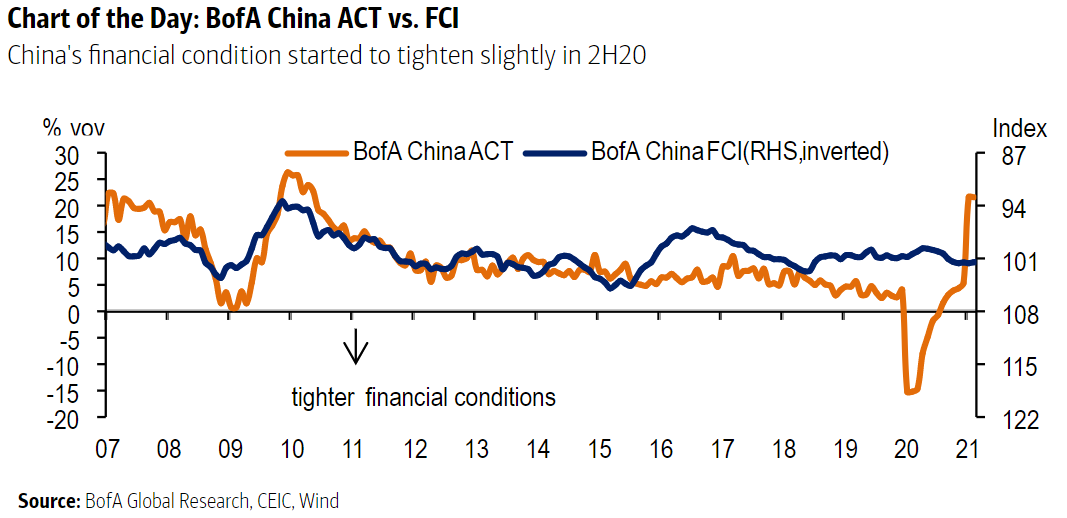

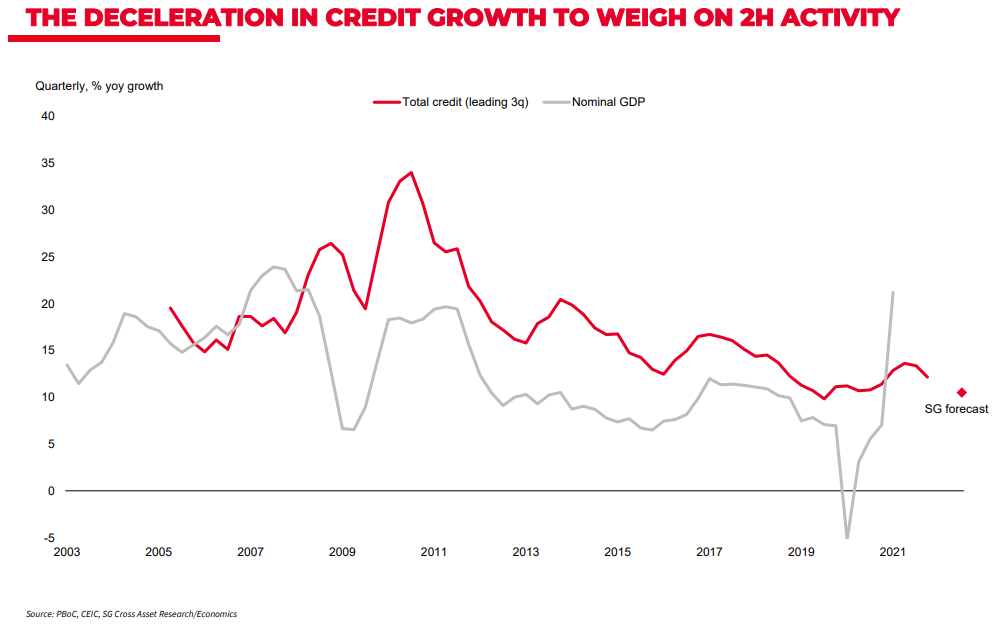

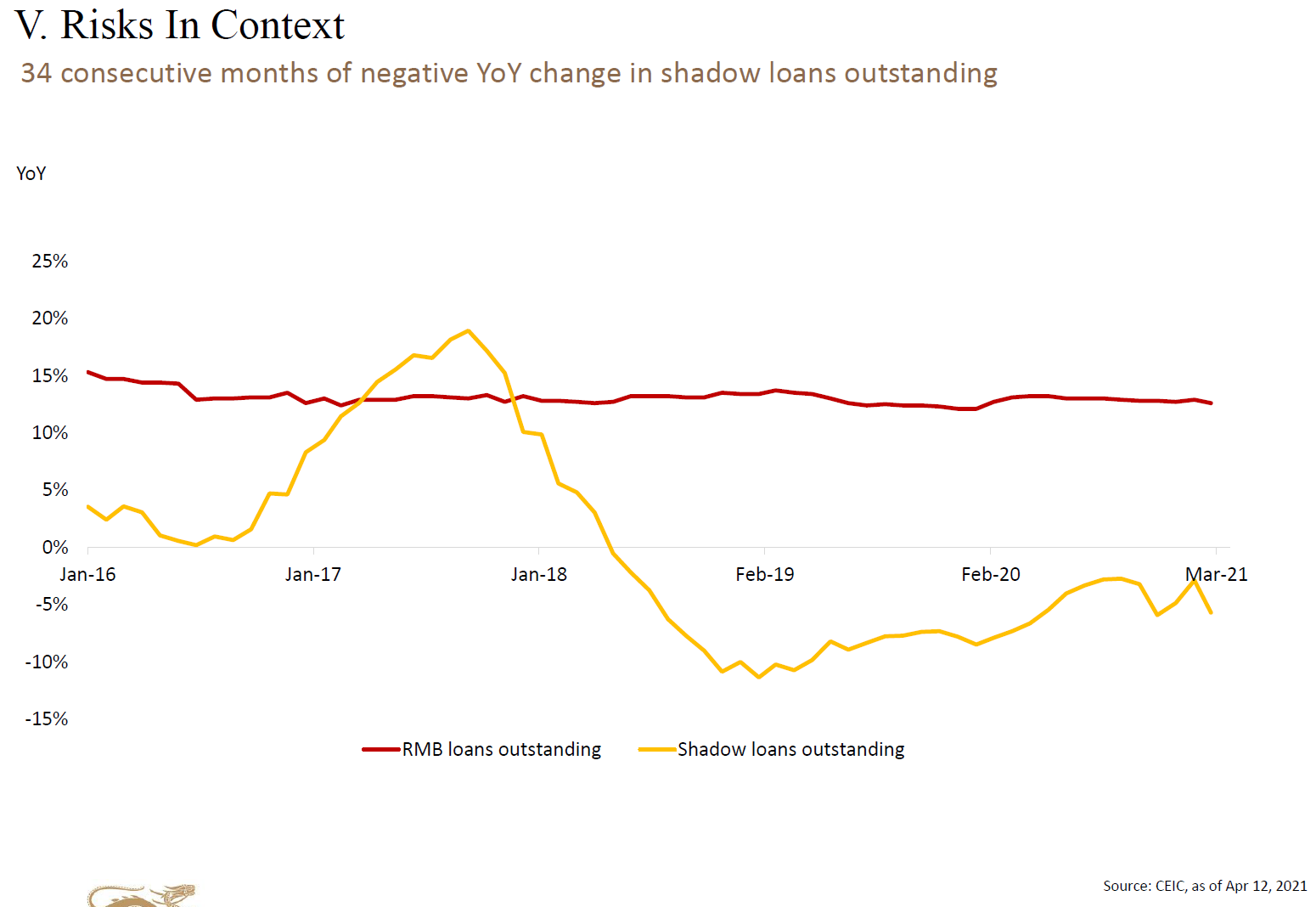

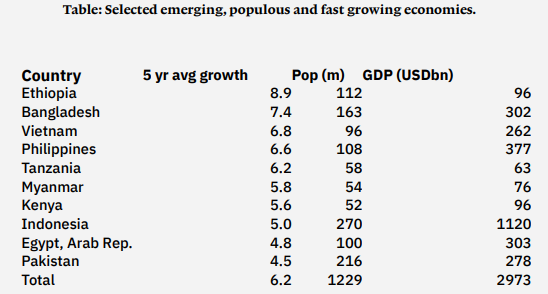

China: The Sum of All FearsOne thing hasn't changed since Donald Trump's departure from the White House. China remains high on the agenda in the U.S., and in almost every sphere conflict seems inevitable. The top three China stories on the Bloomberg.com website at the time of writing were: Momentum Grows in Congress for Legislation Confronting China, 'Diplomatic Boycott' of Beijing Olympics Added to China Bill, and Australia Cancels China's Belt and Road Deal With State. A similar snapshot at more or less any other time in the last few months would have yielded a similar picture. Beyond fears that an assertive China will go to war, either commercially or even militarily, there is a set of almost equally alarming questions that concern the country going in the opposite direction: Will it stop growing and deprive the rest of the world of its desperately needed buyer of last resort, or could China even succumb to a Lehman-level credit crisis that sends the world into turmoil? None of these questions can be lightly dismissed, although they owe as much to sentiment in the West as to China's actions. A decade or so ago, it was taken as read that China was really a capitalist economy, communist in name only, steadily easing its way toward full membership of the club of liberal democracies; now it has become popular to refer to the entire country as the CCP, for Chinese Communist Party. There is real and disquieting change afoot in China, but that is balanced by a shift from undue complacency to exaggerated alarm in the U.S. and western Europe. And the contradictions at the heart of the Chinese model remain as contentious, and as baffling for outsiders, as ever. So, here is a brief illustrated guide to the greatest fears and most alarming questions about China. Is China slowing down?It looks very much like it. That doesn't mean that it's shrinking, but the hectic growth of the recent past is over. Base effects from last year's Covid-19 trauma make all kinds of economic effects hard to discern, but if we look at quarter-by-quarter data, the first three months of this year saw the slowest Chinese GDP growth in a decade (barring of course the first quarter of 2020): The "good" news from activity data is that volumes of passengers and traffic congestion in the big cities' metro systems are back to where they were in 2019, as shown in the following chart from Wei Yao and Michelle Lam of Societe Generale SA. There have been a few Covid outbreaks in the first months of this year, but they have been squelched effectively, and shouldn't affect growth too seriously.  A sectoral breakdown shows that the slowdown was chiefly driven by construction and leisure. Information technology continues to grow:  Meanwhile, according to the Financial Conditions Index maintained by BofA Securities Inc., financial conditions began to tighten in the second half. Until the Covid shock scrambled the economy, this tended to move directly in line with BofA's Activity Coincident Tracker for China, with the country's recoveries from the global financial crisis in 2009, and then from the devaluation of 2015-16, both rooted in easing conditions. There has been no such dramatic easing this time, and further tightening seems likely:  So, in short, it makes sense to assume that Chinese growth is going to slow. That at least has positive implications for the next question: Is China bound for a financial crisis?Obviously, there is a risk that macro-prudential measures to avoid a systemic crisis will cool the economy. The evidence is that authorities will try hard to avoid overheating and crisis — which will have the side-effect of slowing growth. As this chart from SocGen shows, credit expansion is easing, and this has a strong tendency to lead economic growth:  China has already tried hard to rein in one of the most alarming excesses of recent years, which was its reliance on the shadow banking system to funnel credit that helped the economy bounce back from the badly handled 2015-2016 devaluations. The chart is from Matthews Asia:  It looks as though the Chinese leadership shares the concerns of the rest of the world about the possibility of a Lehman-style crisis and is focused on averting that risk. That means the chance of a major financial crisis looks low, but it reinforces the likelihood of slower economic growth. Does it matter so much?Maybe it doesn't. Stewart Paterson, who runs the Capital Dialectics research service, argued that China was being superseded, in a fascinating debate with Andy Rothman of Matthews Asia (a long-term bull on China's economic and market prospects) hosted by the ERIC investment aggregation site. Paterson said: during the five years to 2019 (pre-COVID), a group of no less than 39 countries, with a combined population twice that of China's, was growing as fast or nearly as fast as China was. India of course accounts for half of the population in that grouping and tied with China for 11th place in the five-year growth ranking. But outside of India, there is a grouping of near equal population size rivaling the two Asian giants. Nearly half the world's population is therefore living in fast growing economies.

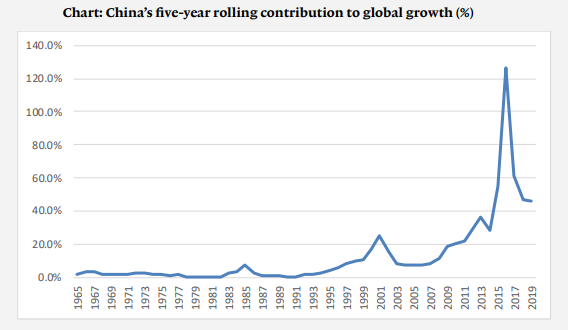

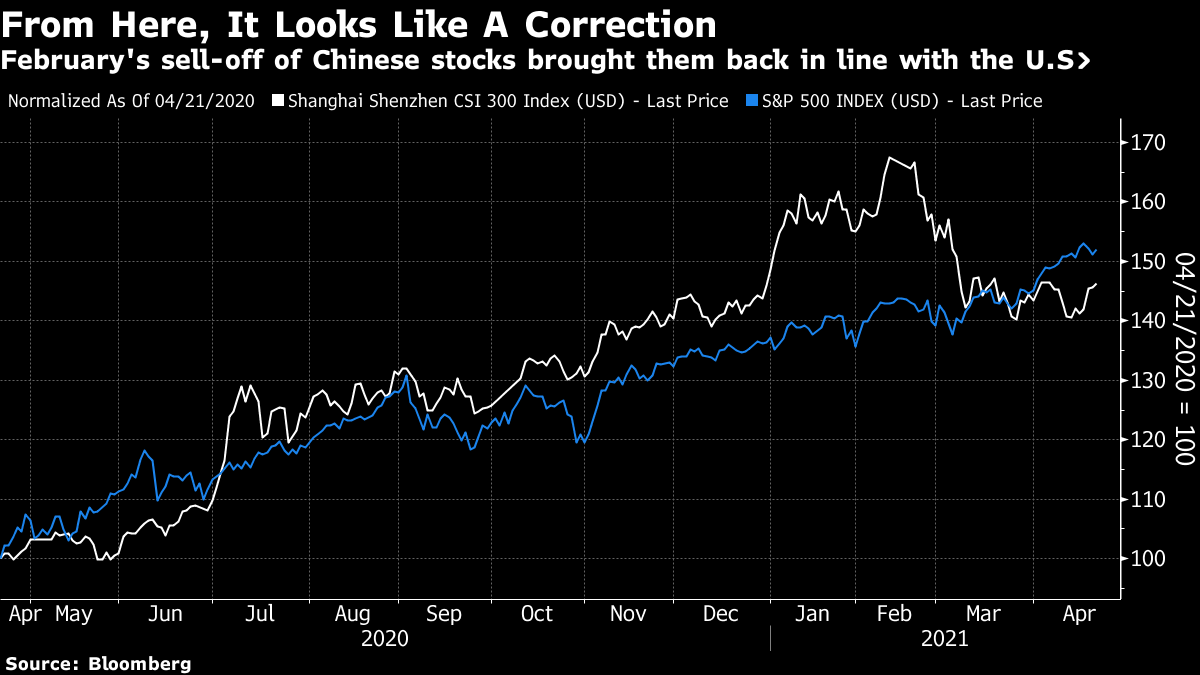

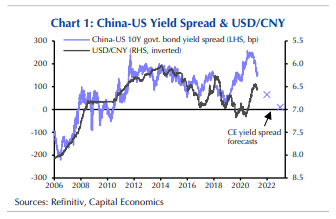

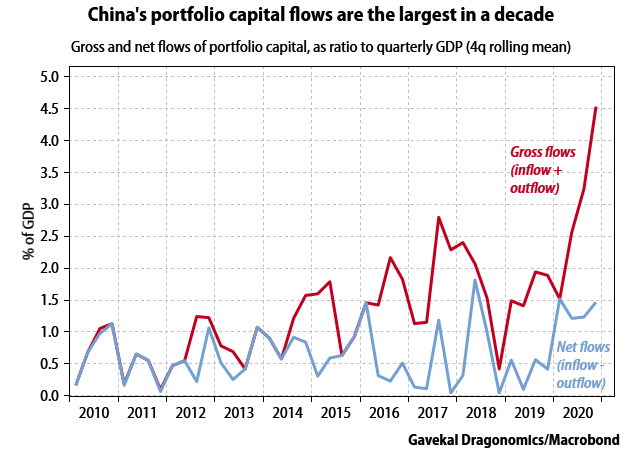

The following group of countries combined have much the same population as China, and have enjoyed a faster growth rate (from a much lower base in some cases) over the last five years:  Paterson's list doesn't lend itself to a catchy acronym like the BRICs, named for Brazil, Russia, India and China. Many look terrifying places to invest, with military or communist leadership. But that isn't so different from China — and on the face of it they should be a better bet to grow at China-like rates for the next few years. From 2011 to 2016, China's economy expanded by $3.7 trillion while the global economy as a whole grew by just $2.9 trillion, as the euro zone battled its crisis and the U.S. plodded. Those years are over:  It's possible that China will steadily grow less important economically — although if this were to happen, it might affect the country's attempts to assert itself in other ways. Are China's stock markets crashing?Domestic A-shares have just endured a sharp correction, though it's questionable whether this need have any significant effect elsewhere. The CSI-300 had been rising steadily in line with the S&P 500, briefly took off in December, and then corrected in February. China's markets are prone to bubbles and crashes, largely because the government reserves the right to intervene, and often does it in ham-fisted fashion. This incident isn't on the scale of a crash:  What about the bond market? And the currency?Chinese bonds have enjoyed a big influx of investment, in part because of a massive spread in yields on offer compared to comparable Treasuries. That advantage has steadily fallen with the recent rise in Treasury yields. One key effect has been to strengthen the yuan, as demonstrated by this chart from Capital Economics, which shows the spread in yields and the dollar exchange rate:  Chinese authorities have responded in part by encouraging capital outflows, which tend to reduce upward pressure on the currency. But this is unlikely to continue indefinitely. As this chart from Gavekal shows, the excitement about Chinese assets over the last year, as the country was first to emerge from pandemic shutdowns, has been dramatic:  To quote Wei He of Gavekal: Those rising inflows have led to a steady march upward in the renminbi's trade-weighted exchange rate since mid-2020. The People's Bank of China has been refraining from direct intervention in currency markets, so authorities have instead encouraged more outflows of portfolio capital to offset that upward pressure. The resulting combination of bigger inflows and bigger outflows means that gross capital flows are now the biggest in a decade. But the impact of larger capital outflows has been mixed so far, and authorities remain wary of dramatic moves to further open the capital account. Policymakers' best hope is that capital inflows cool off in 2021, which looks probable as rising US treasury yields are making Chinese bonds less attractive at the margin. Otherwise, there will be more pressure on the PBOC to intervene, directly or indirectly, to hold down the renminbi.

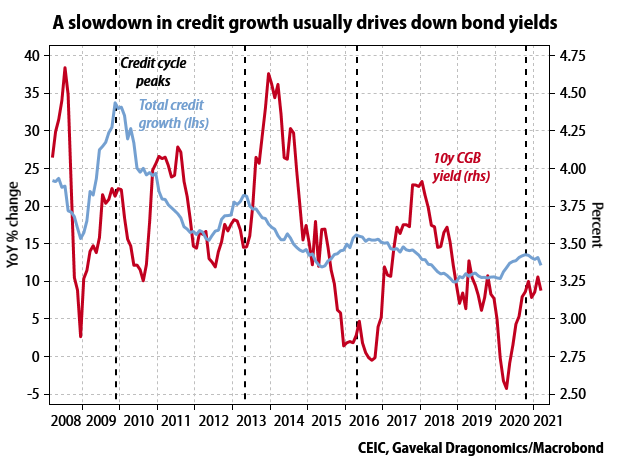

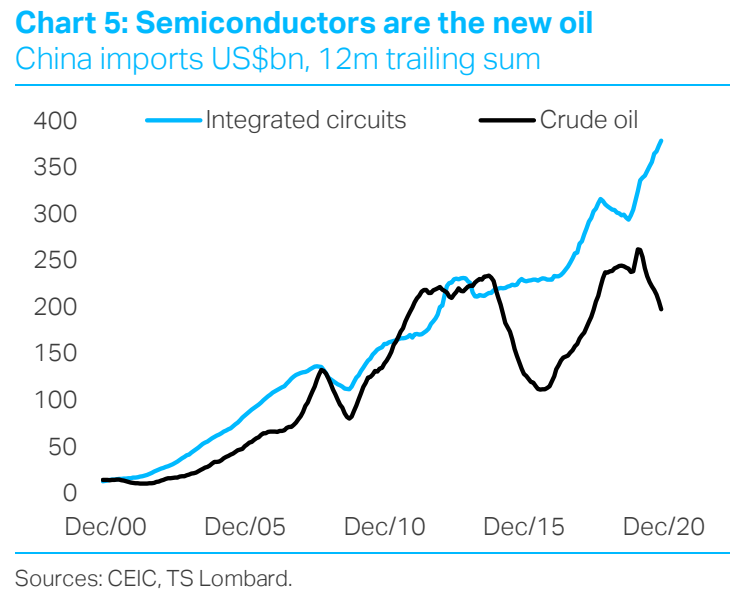

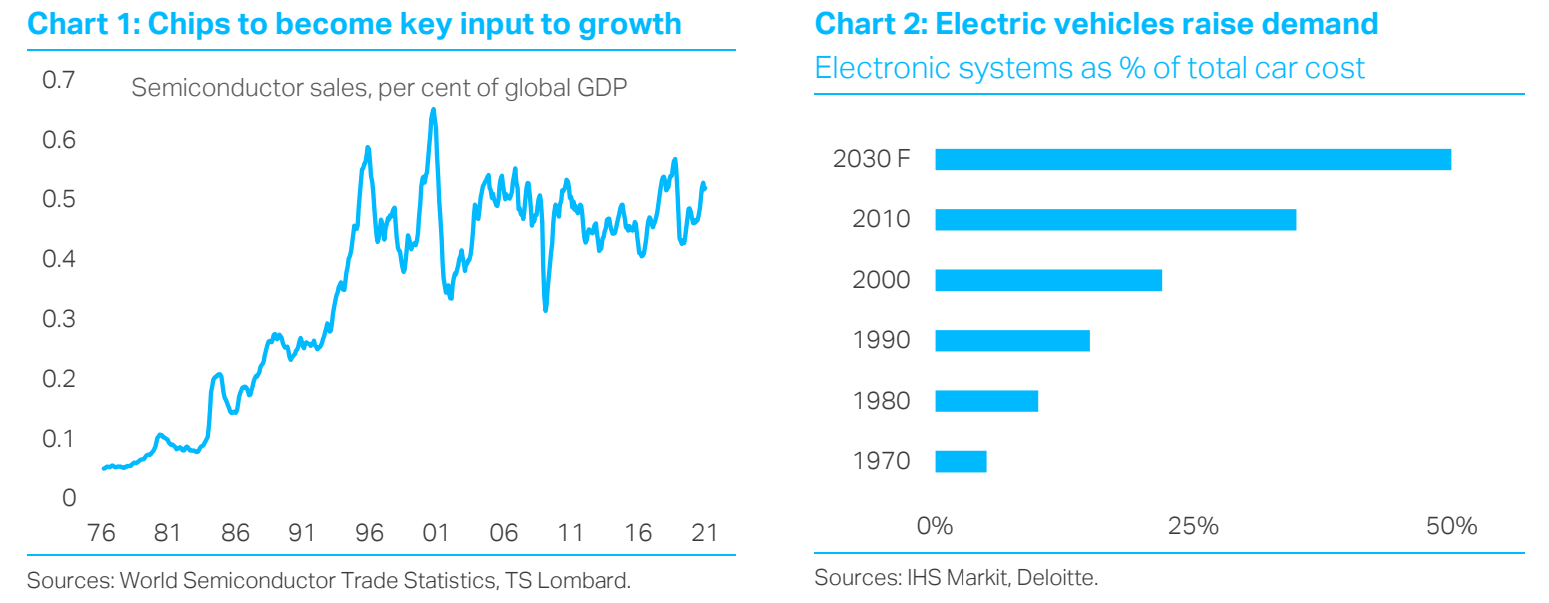

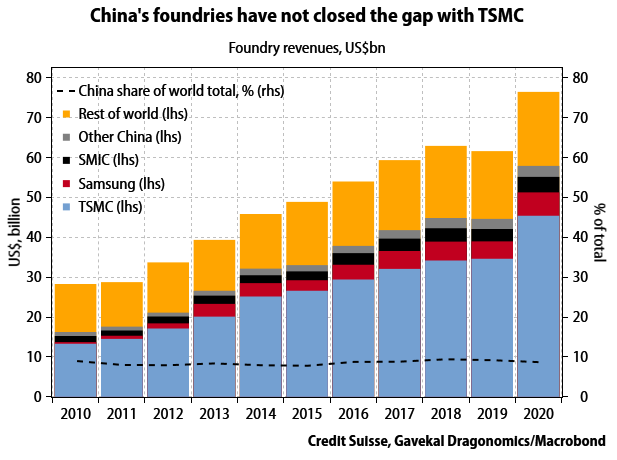

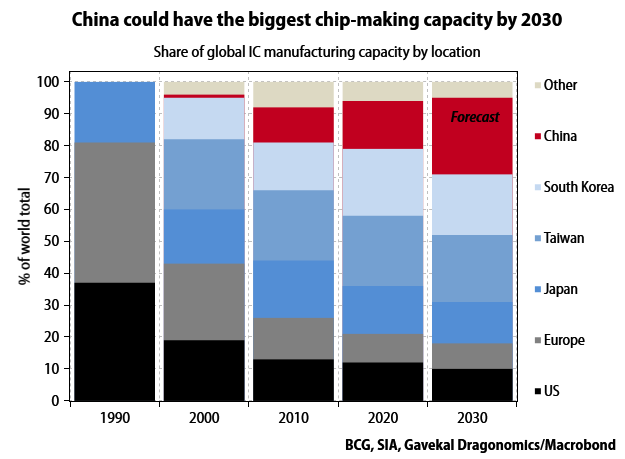

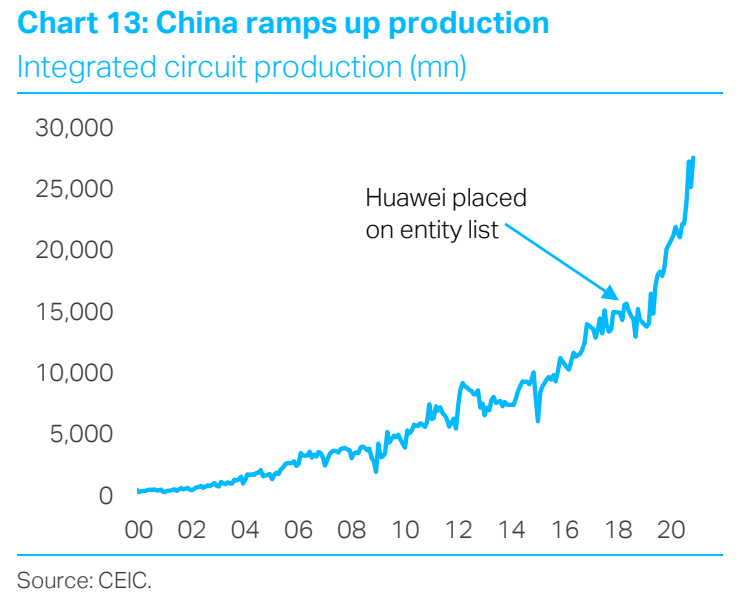

Meanwhile, when measured on a real effective basis against a broad range of countries, the currency is its strongest since the summer of 2015, when a sudden and poorly communicated devaluation briefly created near-crisis conditions in global markets. This isn't ideal for China's economy.  But even if Treasuries reduce some of their relative attractions, there are reasons to expect Chinese bond prices to rise and yields to fall. All the main companies that compile global bond indexes have now started to include China, which virtually guarantees inflows. A slowing economy also helps bonds. As this Gavekal chart shows, lower credit growth (which seems likely) generally means lower yields on Chinese government bonds:  Is China in a state of economic war with the West?There are many dimensions to this question, but the most important at present is the supply of semiconductors. China needs them more than oil, as this chart from TS Lombard shows:  China isn't alone. Semiconductors are important for everyone, and demand will increase greatly if the electric vehicle revolution proceeds as many hope:  This is now perceived as a source of strategic vulnerability, just as it is in the U.S. To control their own destiny, countries need to be able to guarantee a supply of semiconductors. China has been trying to increase its production over the years, but it continues to lag Taiwan, of all places. As this chart from Gavekal shows, China's entire production is still smaller than that of Samsung Electronics Co. and far behind the output of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.:  Brace for China to deal with that. Self-sufficiency is important to the regime. Relying on other producers, particularly Taiwan, is to be avoided. According to Gavekal, China's intention is to supplant South Korea and Taiwan as the place with the biggest chipmaking capacity by the end of this decade:  Should we see this in competitive terms? TS Lombard shows that China's production of semiconductors shot up after the U.S. clamped down on Huawei Technologies Co. That incident turned technology into a front in the confrontation between the two countries:  Economic war might be too strong a word, but semiconductors have something like the strategic importance that oil used to have. And as Taiwan remains the world's dominant supplier, the strategic importance of the island only grows. And it was already of immense importance to China in any case. We can all look forward to hearing much more about Taiwan. Survival TipsOK, some Chinese references from pop music I was brought up with. Here's Hong Kong Garden performed live by Siouxsie and the Banshees (and introduced by Peter Cook), Wishful Thinking by China Crisis (and no, I don't think it's wishful thinking to avoid a China crisis, but it's a nice song), White China by Ultravox, China Girl by Iggy Pop, and China Girl again as covered by his friend David Bowie. Much more recently, there's Coldplay and Rihanna aping Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon in the video for Princess of China, or U2's Breathe (which might not sound like it has much to do with China, but has some strikingly prophetic lyrics at 2 minutes in). |

Post a Comment