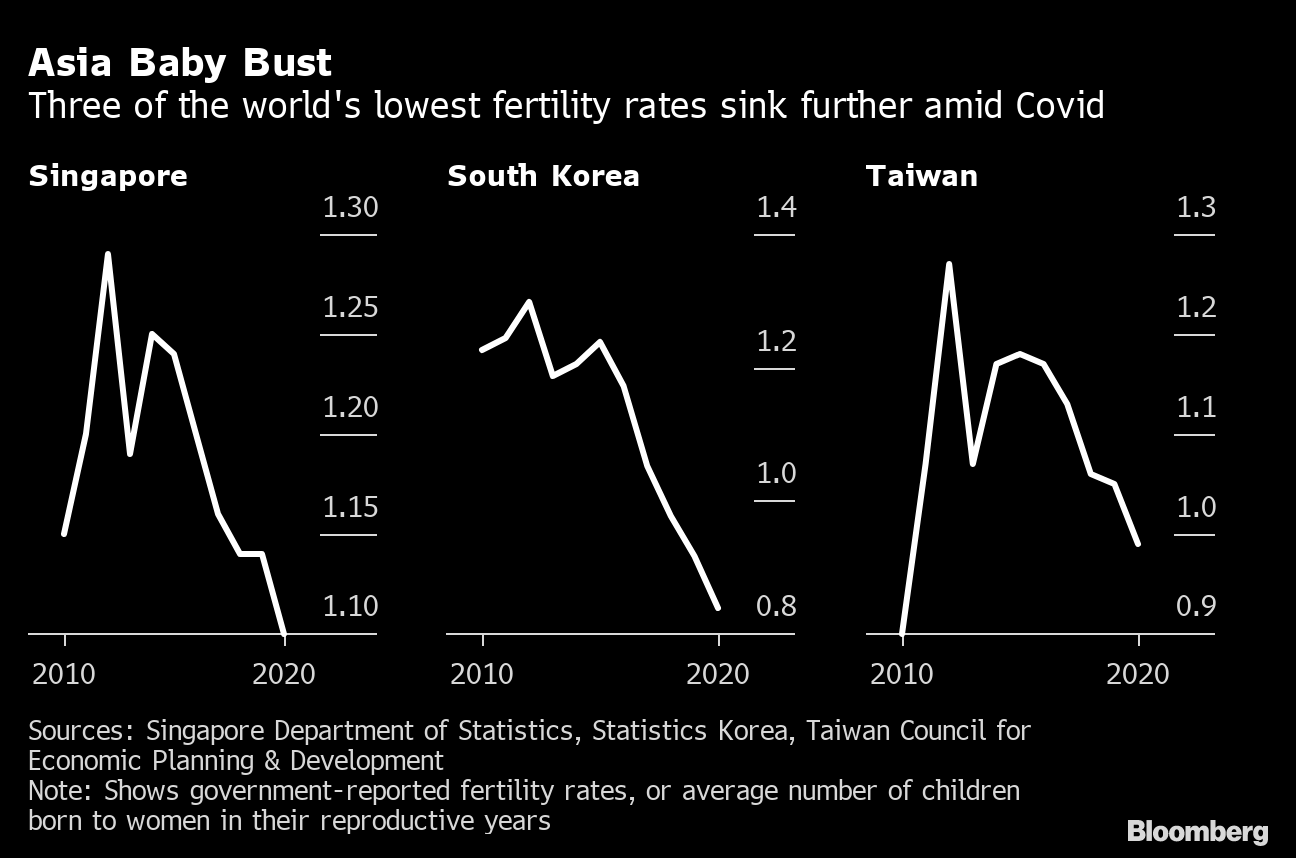

After years of warnings about falling birth rates, the other logical shoe is starting to drop: Some countries' populations are actually shrinking. South Korea, home to the world's lowest birth rates, welcomed 11% fewer babies last year and saw its population drop for the first time ever. Same for Taiwan, which had been forecasting the decrease but not until 2022. Japan's population continues to fall, posting new record shrinkage last year -- the country's lost more than 1 million people, or 0.8% of its population, in the past three years. China's on the same trajectory, with a 15% decline in registered births last year. A Chinese state-backed think tank estimates that the country's population could peak as early as 2027. The pandemic baby bust is helping accelerate these demographic trends all around the world, including in the U.S. From an environmental standpoint, population decline isn't the worst thing, but policymakers and economists worry about the pain of a shrinking workforce against the rising costs of an aging population.  There's only so much a government can do to stem the decline. One is to try to shore up falling birth rates. Singapore, for example, is considering a S$3,000 ($2,200) "baby bonus" to encourage parents who might've put off baby-making due to the pandemic. Korea's trying a different tack. The government said that it could strengthen support for single parents and non-traditional families, including unmarried couples with children. That could include same-sex families, who heretofore haven't been recognized by the state. China, where the birth rate has long been a policy issue, is doubling down on what Bloomberg Opinion's Adam Minter rightly called "traditional and often sexist notions" of family, most recently introducing new barriers to couples looking to divorce. With every new example of a country trying—and failing—to reverse a falling birth rate, it should be obvious that we can't procreate our way to economic growth. Experts suggest that most countries around the world have room to increase workforce participation, though, particularly among women. To do that requires different types of policies, the kind that don't make aspiring parents choose between paid work and a family.—Isabella Steger |

Post a Comment