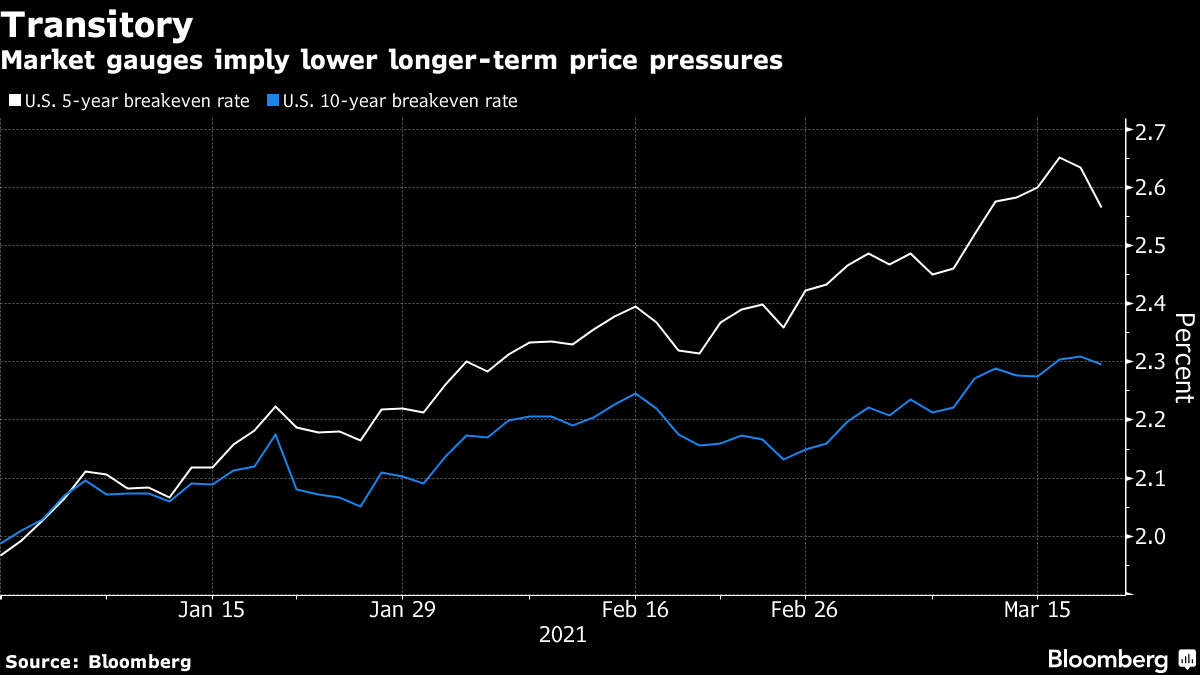

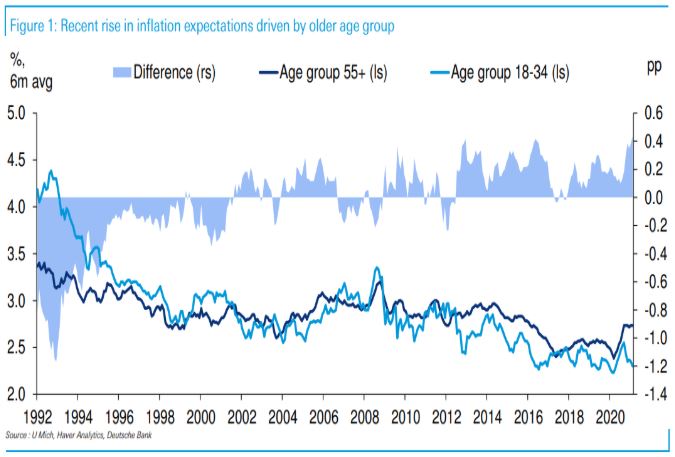

| Welcome to The Weekly Fix, the newsletter that hopes your second dinner isn't ruined by a late announcement on SLR. -- Emily Barrett, Asia cross asset reporter The insufficient statistic"The unemployment rate is an insufficient statistic." It's the quote of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell's press conference* and a major bond-market headache right now. In his latest policy update, Powell spent a lot of time talking about the central bank's commitment to an inclusive recovery with jobs for Americans who have suffered disproportionately in the pandemic crisis. He talked about policy makers looking beyond headline unemployment figures to gauge progress on that goal. This is a welcome shift for a Fed that's arguably more focused on Main Street than ever before. For bond investors, it's also unfamiliar territory. Powell's emphasis on letting the economy run hotter to get to an unspecified level of maximum employment breaks definitively with the central bank's history of acting preemptively on inflation risks. Powell tried to put the new strategy in a recent historical context, likening the employment-focused policy guidance to what was offered in 2012 with QE3, when then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke said he was targeting substantial improvement in the labor market. But we're in a substantially different place. At that time the Fed wanted unemployment at 6.5% before raising rates, almost double the level achieved just before the pandemic (with no sign of inflation). It's currently at 6.2% -- and for African Americans, 9.9%. The market will have to find its bearings with the Fed's labor market goals since the central bank abandoned its prior interpretation of levels where unemployment has fallen far enough to stir wage pressures. Compared with an inflation target, "employment is a lot harder to price and the relationship between employment and wages, and wages and inflation has been shifting over time," said Vanguard global rates and currencies strategist Anne Mathias. It looks like the Fed's newfound patience riled a lot of bond marketeers this week, despite the central bank's pretty consistent message since it unveiled the new average inflation-targeting strategy late last year. To recap, the Fed's new goal is inflation around 2% over time. Given the years of shortfall that means interest rates should stay on hold until price increases appear to be running slightly above that level for a while. So Powell aimed to head off the market's rising expectations for rate hikes, and any fears of an inflationary spiral, as the economic numbers improve. Arguably the *bigger controversy of the webcast was Powell's assertion that "you can only go out to dinner once per night" -- which briefly outraged the gourmand subset of the FinTwit community. But his broader point, that the inflationary rebound in this recovery has its limits, is key. People who stopped eating out will start again. However, they're not going to be buying a year's worth of missed teriyaki (with the possible exception of those who know who they are). And that's why the breakeven inflation curve is looking super-distorted right now, with a smorgasbord-sized overhang at the front. Inflation will be higher as pent-up spending is unleashed, and with the help of stimulus checks. But rates further out suggest that inflation will return to the Fed's target.  Fed plans, bonds laugh.That expectations curve may not be at all unrelated to what's going on with rate-hike pricing. Despite a stronger outlook for growth and inflation, the Fed's updated projections this week showed the bulk of policy makers don't envisage a rate hike before 2024. Traders don't share that view -- they're braced for lift-off as soon as the first quarter of 2023. And not only that, they're building a more-aggressive tightening cycle afterwards. Those hedges may be premised on the view that the Fed will have to move faster to rein back price pressures than it currently expects. Our rates guru Edd Bolingbroke sees the succession of hikes piling up in the Eurodollar strip, with a full percentage point move by the end of 2024.  The Generation Gap Strikes AgainFew people are as beset by fears of runaway inflation as Ray Dalio, who's just about fed up with investing in financial assets altogether. And he's not keen on cash either. Incidentally, that might make sense from a demographics perspective -- Deutsche Bank's Jim Reid this week shared the below chart from Matt Luzzetti, showing how median expectations for inflation among older Americans have hit a near six-year high, while those of the Gen Z crowd have barely budged since the pandemic shock.  Photographer: Deutsche Bank Photographer: Deutsche Bank The BOJIt's also possible that the rise in 10-year yields may have less to do with inflation fears than the activities of offshore Treasury investors. One theory behind the spike in the benchmark rate to as high as 1.75% Thursday in the U.S. (the day after Powell's speech) was a bout of selling by Japanese investors waiting for the fresh liquidity of the European open to offload their holdings. Janney Montgomery Scott's Guy LeBas raised that possibility on Twitter, noting that Bank of Japan policy could have sparked the move. It's not often we get to talk about the BoJ as a market event these days, so we'll run with it. The central bank made a couple of key adjustments to its policy Thursday, intended notsomuch to pull back its legendary support as to equip it for the long haul. This week's policy decision included the results of a framework review. The upshot is the central bank is now officially allowing the 10-year yield to fluctuate slightly more around its 0% target -- a quarter percentage point either side. That step is likely meant to try to shake up Japan's moribund government bond market, as the central bank's heavy interventions over decades-long attempts to revive inflation have squeezed out traders and market makers. Among other tweaks, the BoJ also ditched its 6 trillion yen ($55 billion) guide for annual purchases of exchange-traded funds. It's sticking with an upper limit of 12 trillion yen, for the option of stepping into the market in times of stress. The bank also added lending incentives that could grow if interest rates were to fall further. Our Japan reporters Toru Fujioka and Sumio Ito highlighted that the step gives policy makers more flexibility to cut rates further below zero, by cushioning the blow to struggling regional banks. Ultimately the changes, while not big market movers, show the BoJ focused on improving the efficiency and sustainability of its already massive interventions in ways that its international peers in Europe and the U.S. aren't yet forced to. Bonus PointsGot $93 million? You may be able to boost Bitcoin's price by 1% All the reasons why fiscal stimulus in the U.S. won't cause runaway inflation Happy belated St. Paddy's day with a Punjabi twist Your moment of Zen: Miniature cranes Every journalist's nightmare question, aka how did we come to this |

Post a Comment