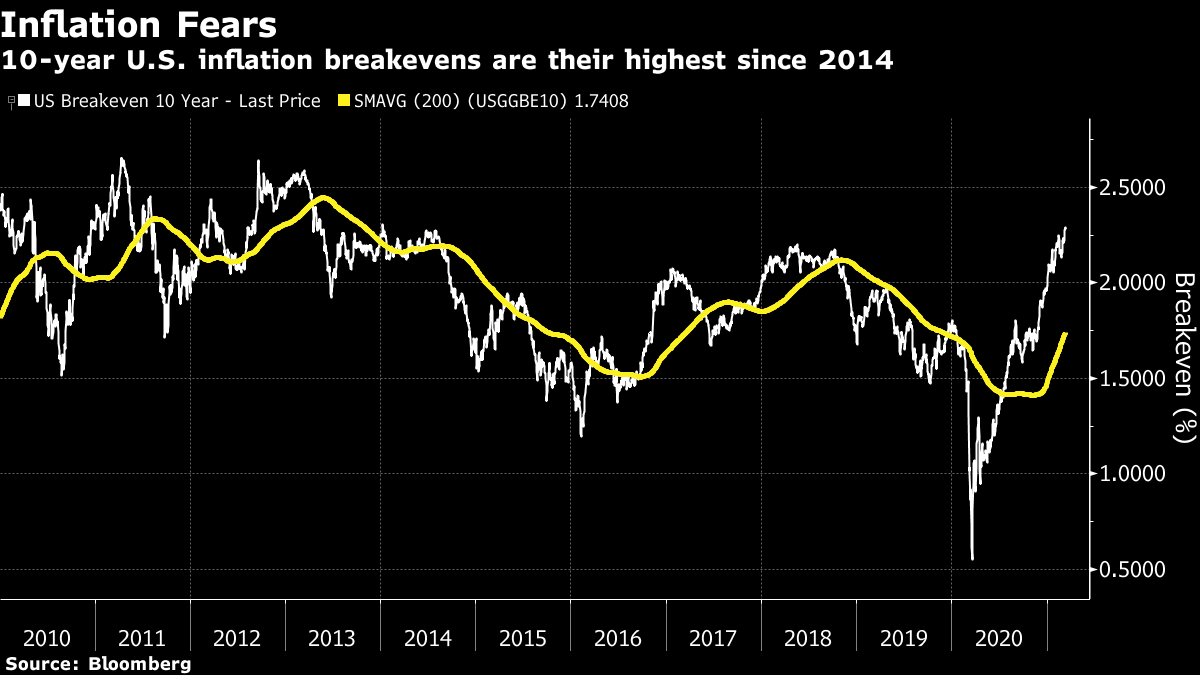

Inflation Hopes and Fears Set FreeGet ready for another week of inflation obsession. Following last week's attempt at calming talk from the European Central Bank, this week brings meetings on monetary policy by the Federal Reserve, as well as the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan. If any of them are inclined to adapt their policy to what they see as coming inflation, they will need to start letting us know about it. I doubt they will feel any great need to signal a change in policy, but the market gives them no choice but to comment on a startling shift in expectations. The week begins with 10-year U.S. Treasury yields at a fresh post-shutdown high of 1.63%. Meanwhile, 10-year inflation breakevens are at their highest since 2014:  In both cases, these levels remain historically low, and shouldn't in their own right concern a central bank that appears to mean it when it says that it wants inflation to average above 2% for a while. And actual measures of consumer prices are still unremarkable, and well below 2%. But the shift in market psychology has been very swift, with the prospect of a return to secular inflation discussed seemingly everywhere. Why?

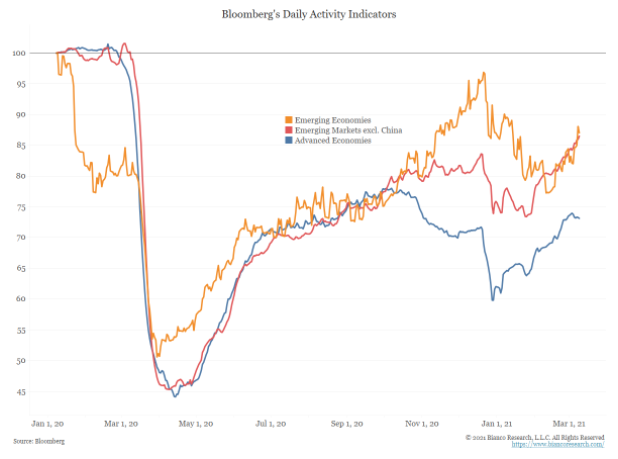

First, there is a straightforward alibi for why inflation pressures haven't shown up in consumer prices yet. This is that economic activity is still far below the levels seen before Covid-19 prompted much of the Western world to shut down last March. The following chart was put together by Bloomberg Opinion colleague James Bianco from Bloomberg daily activity indicators. The reading remains 25% below its pre-pandemic levels in advanced economies:

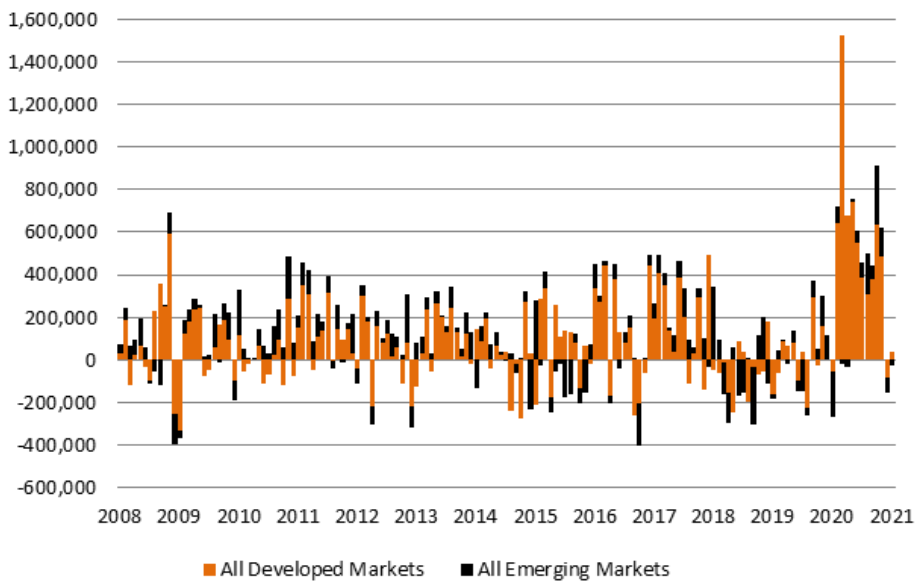

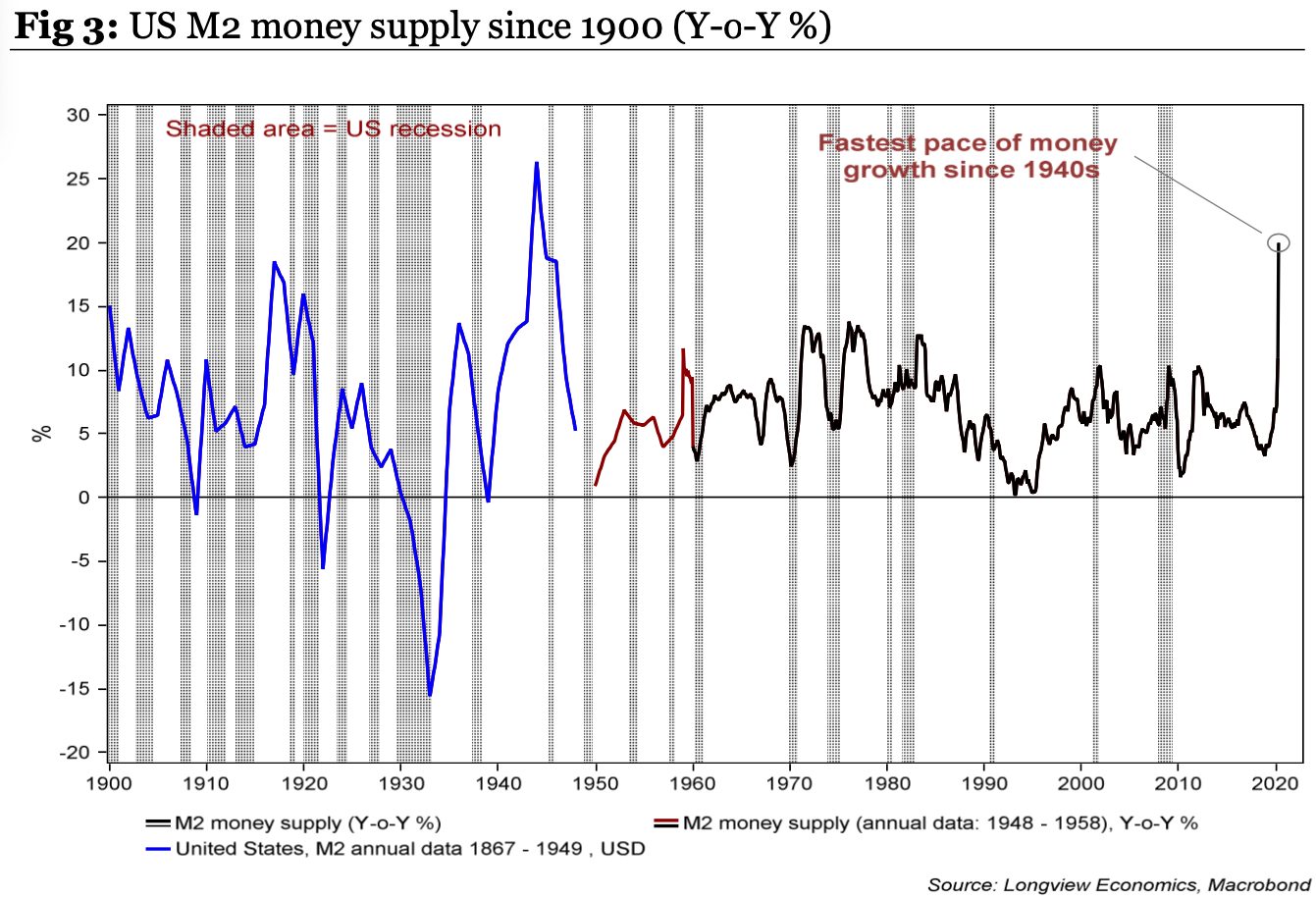

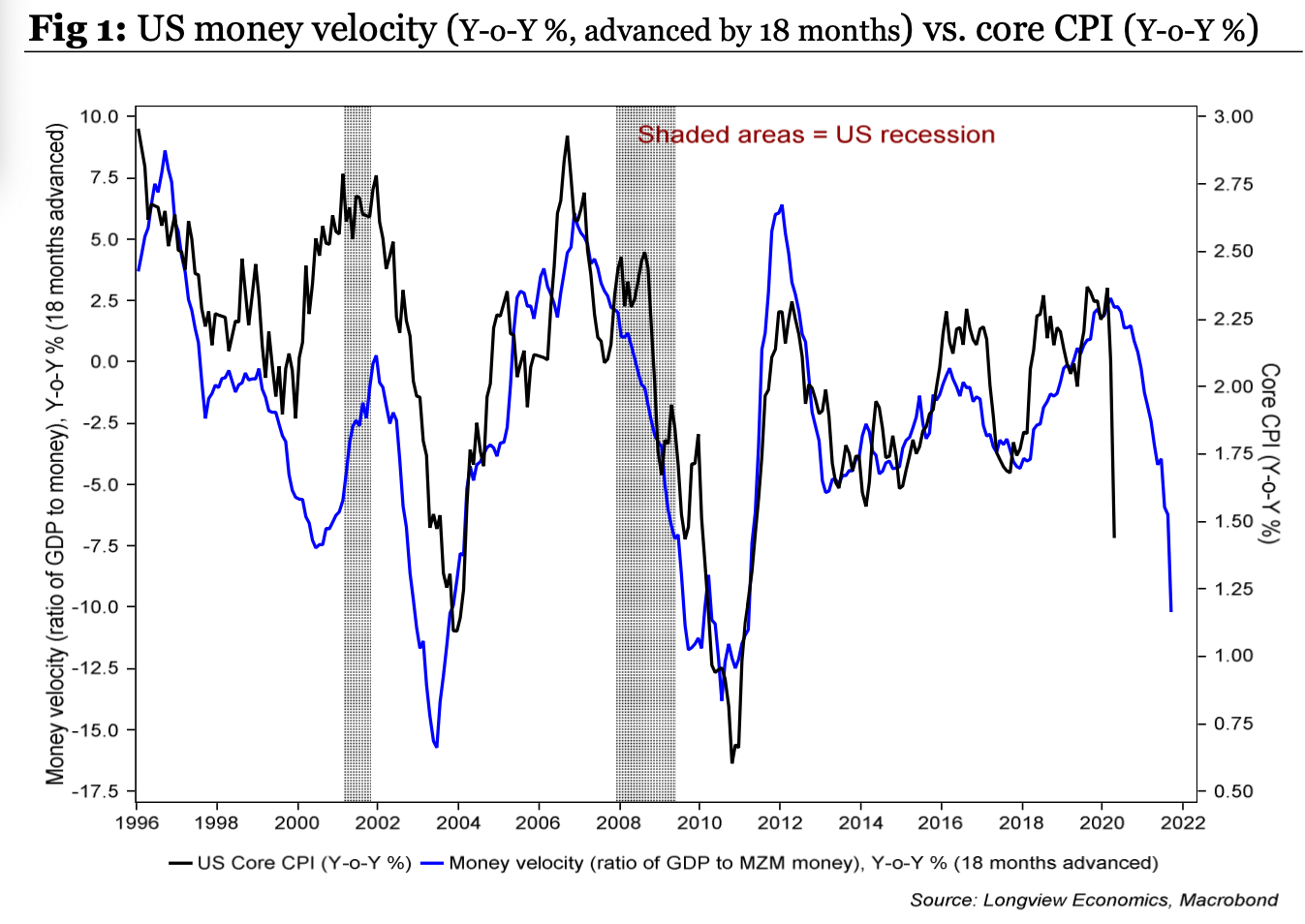

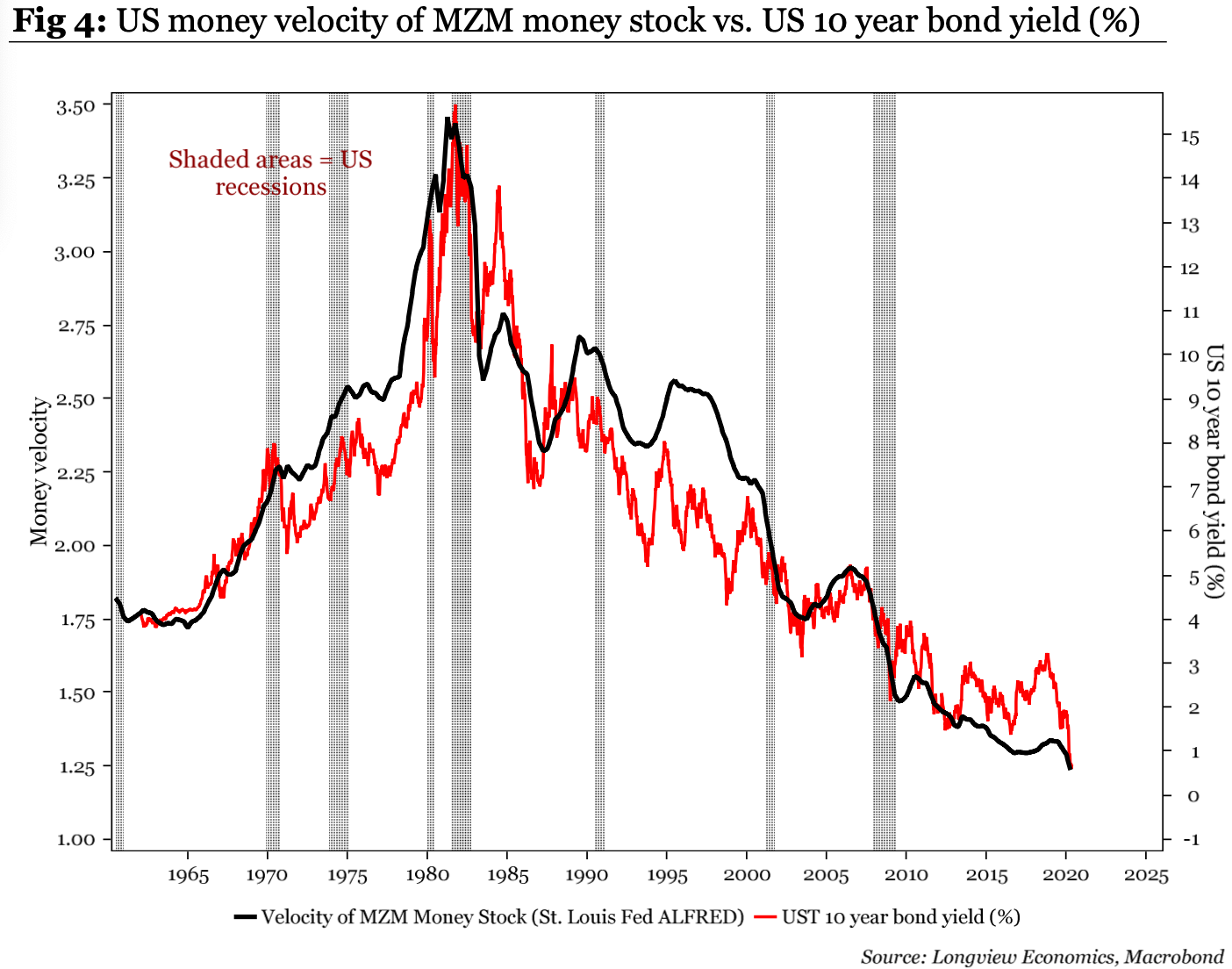

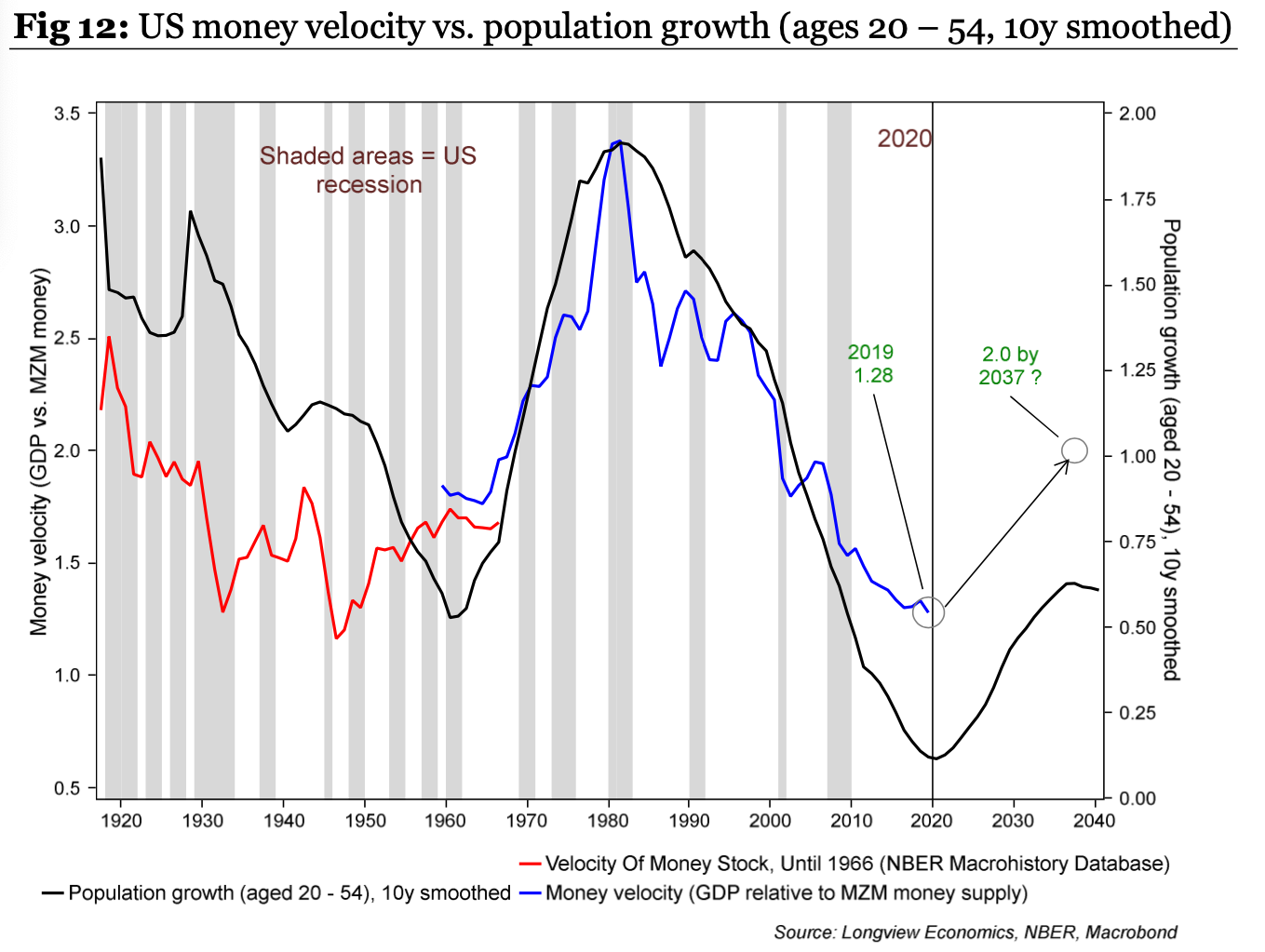

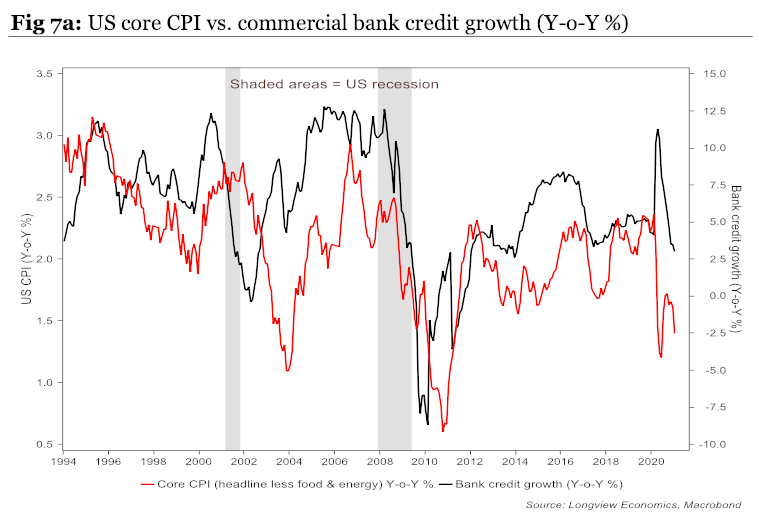

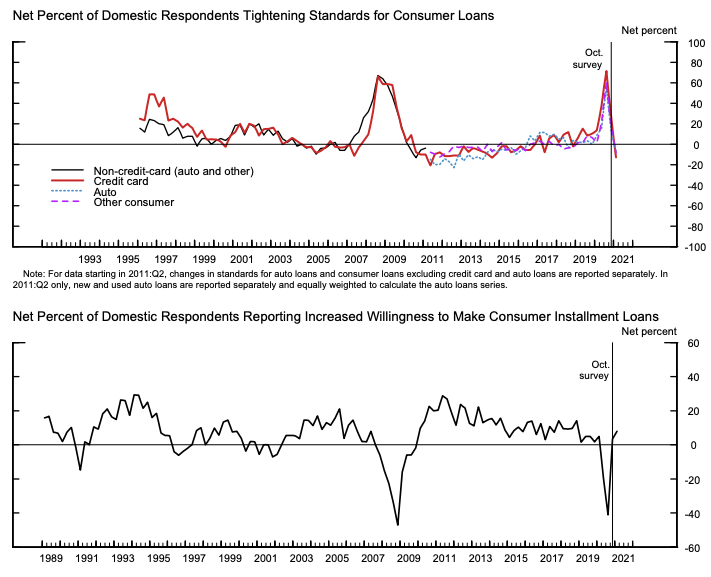

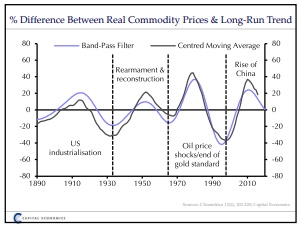

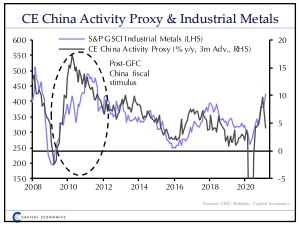

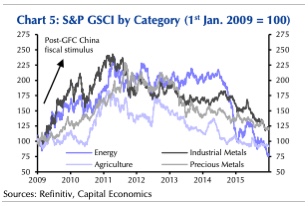

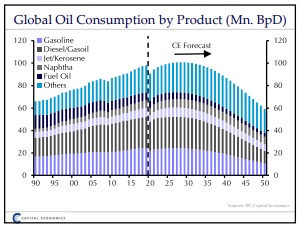

Beyond that, there are a number of ways to approach inflation and how it happens. The old monetarist equation MV = PQ, which holds that price levels (P) are a function of the supply of goods (Q), money supply (M) and the velocity with which that money moves around (V) remains popular. A big increase in money supply will therefore help to create inflation, though not necessarily if it fails to circulate much (which is arguably why inflation remained supine after the desperate money-printing that followed the global financial crisis). As the following chart from CrossBorder Capital Ltd. of London shows, there has recently been a massive increase in money supply as central banks expand their balance sheets. The chart is in millions of dollars:  Within the U.S., the increase in broad money, as measured by M2, is without parallel outside times of war, as demonstrated by this chart of 20th century movements from London's Longview Economics Ltd.:  The reason we haven't seen a rise in inflation, then, can only be a fall in velocity. That is what has happened. This chart from Longview measures velocity as the ratio between gross domestic product and the supply of zero maturity money. Velocity so measured last year thudded lower, so it's no surprise that core inflation dropped in its wake:  Velocity thus measured is still falling. Is there any reason to expect it to rise? According to Harry Colvin of Longview, the rise in bond yields of the last few months is a clear signal from the market to expect an increase in the future. Over the last 60 years, the two have tracked each other closely:  Another reason comes from demographics. We are braced for a rise in retirees as a proportion of the working age population, which may well lead at the margin to selling of bonds, and increased bargaining power for unions. (This is the central idea in The Great Demographic Reversal by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan, which we covered in the last Bloomberg book club). Colvin adds a further twist. Millennials are a bigger cohort than the Generation X who precede them, and they are growing increasingly influential. For velocity of money, the key demographic is the 20-54 age group. People in this bracket traditionally spend the most as they go to work and raise families. As he shows, money velocity over time has been linked to the trend of this group.  With the growth rate of the 20-54 population about to turn and increase, we should brace for an increase in money velocity and therefore, as the money supply is so much greater, a return of inflation. Where might a return of velocity show up first? If banks are lending more, which they tend to do when they have repaired their balance sheets and the shape of the yield curve makes it appealing (by increasing the returns for lending over a long term while borrowing over a short term), that generally means that money is moving faster. And over time, there is indeed a close link between inflation and banking credit growth:  Looking at the Fed's surveys of bank senior loan officers, their reluctance to extend credit during the horrors of 2020 has largely gone, and a slight majority are now making it easier for consumers to borrow — but there isn't yet any real enthusiasm for increasing lending to them. This is from the latest survey, for January:  That is what might be called the monetarist case for a return of inflation. Demographics and a healthier banking system will combine to ensure that the vast new quantities of money in the system move around much faster this time. It's a convincing argument to be more concerned, and not to take the lack of inflation after the GFC as a guiding precedent. But it still requires a number of steps to fall into place in the future. Commodity CyclesAnother argument for secular inflation comes from commodity cycles. When commodity prices are rising, virtually by definition consumer inflation also rises as raw materials costs are passed on. Prices of industrial metals and particularly oil have turned up sharply in a way that looks very much like the start of a classic secular up-cycle (covered in Points of Return here). The commodities team at Capital Economics Ltd. in London made an interesting attempt to douse down the hopes (or fears) for a prolonged upward trend in prices. First, this is their own schema of the big waves going back to 1890. The "up" periods have been driven by major waves of investment and construction, from the emergence of the U.S. to the rise of China:  The hype for an uptrend now is driven in part by the notion that the market has itself driven it; falling prices lead to the shuttering of production, reduce supply, and result in an increase of prices. As it takes a long time to add or remove supply for the major raw materials, it isn't surprising that commodity markets move in long cycles. But beyond that, there has generally been a clear catalyst. For this coming wave, the hope/fear is that this will be provided by some form of global "green new deal," with the investments needed to avert catastrophic climate change forcing up the price of raw materials. Naturally, there are political risks to this scenario, which I won't cover now. Beyond that, Capital Economics points out that industrial metals prices have been almost wholly dependent on demand from China. This was true for two decades before the GFC, and it has been even more true in the post-crisis decade. With China apparently reining in credit again, and once more hoping that it can manage the switch from an investment- to a consumption-led economy, and with no other country (even India) in any position to replace China as consumer-of-first-resort, this could be a problem for the thesis that we have a new upward commodity cycle coming, at least according to Capital Economics:  Another reason for concern, according to Capital Economics, concerns a lesson from the GFC. Then as now there was an appalling hit to the global economy, and a big increase in Chinese spending helped a swift recovery. The rebound was so quick that there was a big surge in commodity prices, with metals even topping their pre-crisis level. Once it became clear that this had been a "one-off" stimulus to demand, and the Western world settled into austerity, commodity prices rolled over, and settled into a bear market that would persist for the rest of the decade. China might well disappoint fiscal hopes again. As for the rest of the world, the massive stimulus bill passed last week in the U.S. plainly increases the chances that a new era of expansive fiscal policy is upon us, rather than just a big response to a crisis. Still, the Democrats might easily lose their slender majorities in both houses of Congress at the end of next year. We may be at the dawn of a new era of Big Government in the U.S.; but it's not a certainty. The false rally in commodities after the GFC should be a warning:  A final important issue concerns oil, which has enjoyed a dramatic recovery in the last few months. The last big bull market was accompanied by hopeful speculation about "Peak Oil" — the notion that the amount to be extracted from the ground was finite, and had begun an inevitable and inexorable decline. Higher oil prices were driven by hopes of steadily decreasing supply. They instead incentivized the fracking revolution. Now, Capital Economics warns of a different peak — in demand. Technologies to replace fossil fuels are getting better and better. Investment resulting from any green new deal might drive up the prices of other commodities, but it would be bad for oil. These are Capital Economics' projections for oil demand:  This could be as far off as the predictions of a peak in supply a decade or so ago. But the point remains. A secular rise in commodity prices would put pressure on companies to pass on their costs to consumers. It would be very likely to lead to higher inflation. For the time being, though, nothing is proven and nothing is inevitable. Survival TipsI was banished from the living room at various points this evening as the family's younger generation watched the Grammy awards. Apparently I just don't get large amounts of it, or so I was told. Despite this, I had absolutely heard of the evening's two biggest winners, as they were the two women who had been dominating award ceremonies like this at least since 2009 — Taylor Swift and Beyonce. Both are great musicians and performers. But let me try to offer a couple of pieces of Grammy trivia that my kids didn't know, and which might help you survive any awkward Grammys-related conversations. Beyonce took over the record for the most awards won by a female performer. If you can guess who she overtook, I'd be very impressed; it was Alison Krauss. The bluegrass singer has won 27 Grammys. Here she is in a duet with Robert Plant, singing Black Dog. It's changed quite a lot from the original Led Zeppelin version, in which he was in a duet with Jimmy Page. Meanwhile, Beyonce, with 29 Grammys, still hasn't topped the all-time leader. That would be.... Georg Solti, who amassed 31. He was a remarkable conductor, and I actually saw him conduct once, at the Royal Albert Hall in 1982. It was one of the most extraordinary performances I ever witnessed — of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis. Maybe my kids will be impressed when I tell them that? Have a great week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment