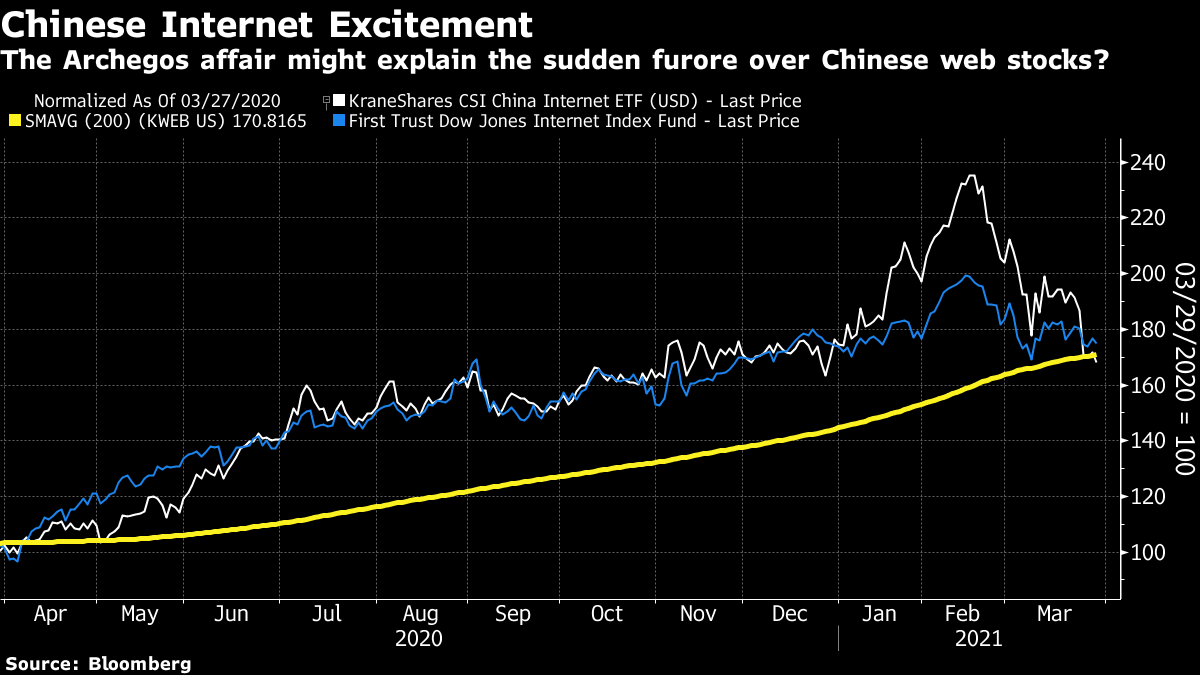

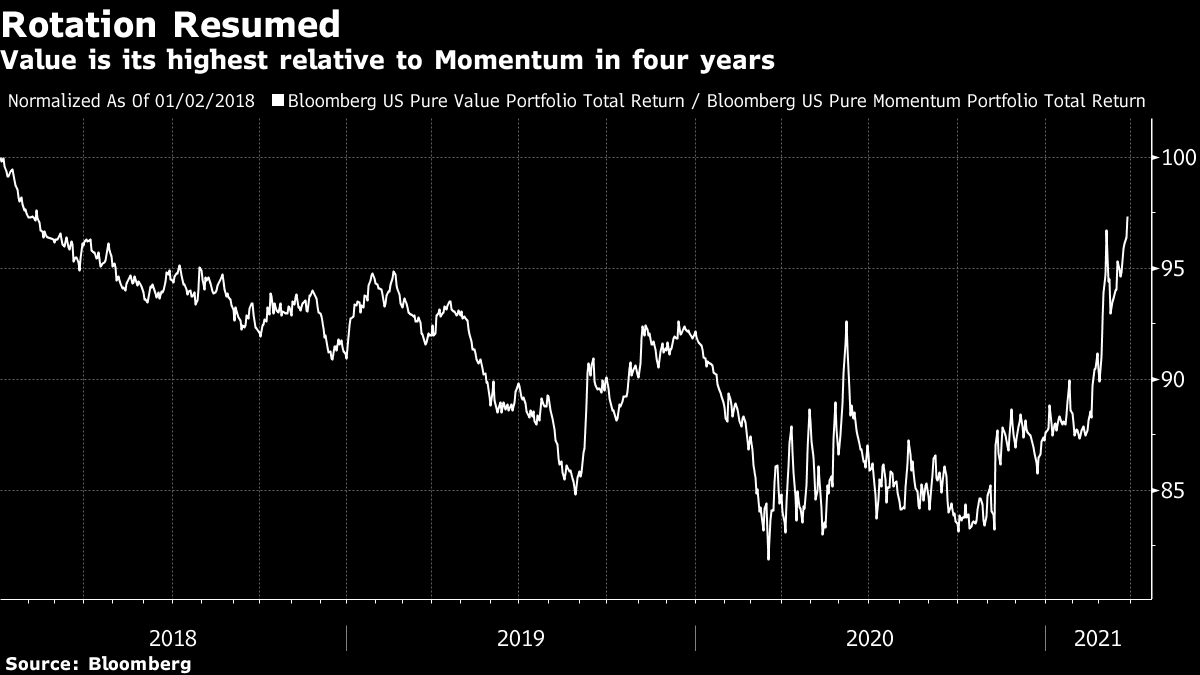

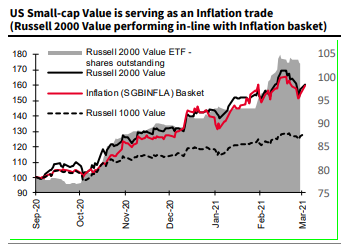

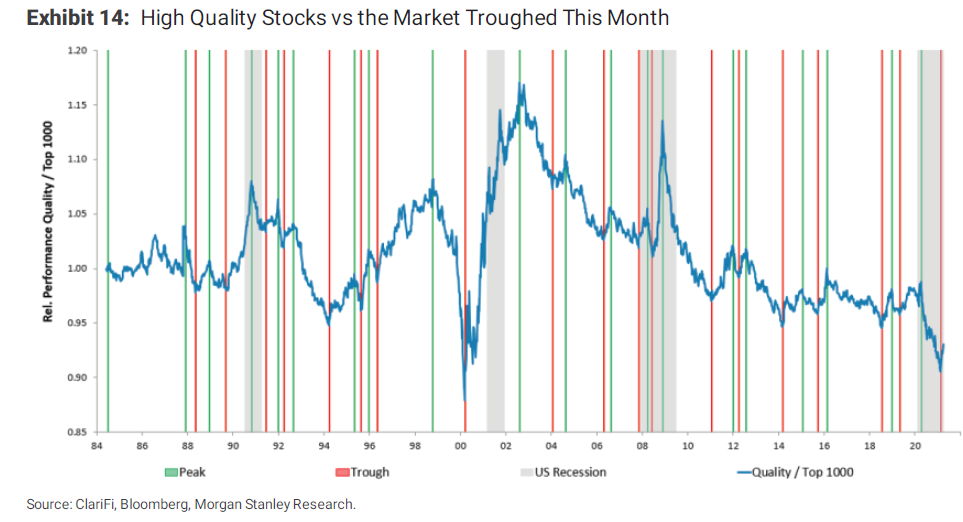

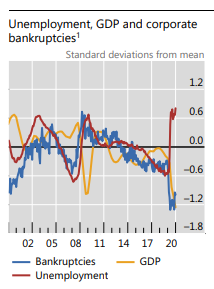

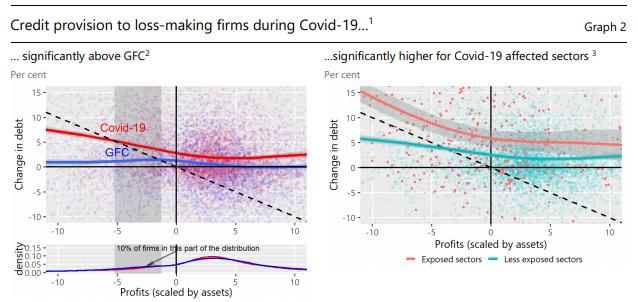

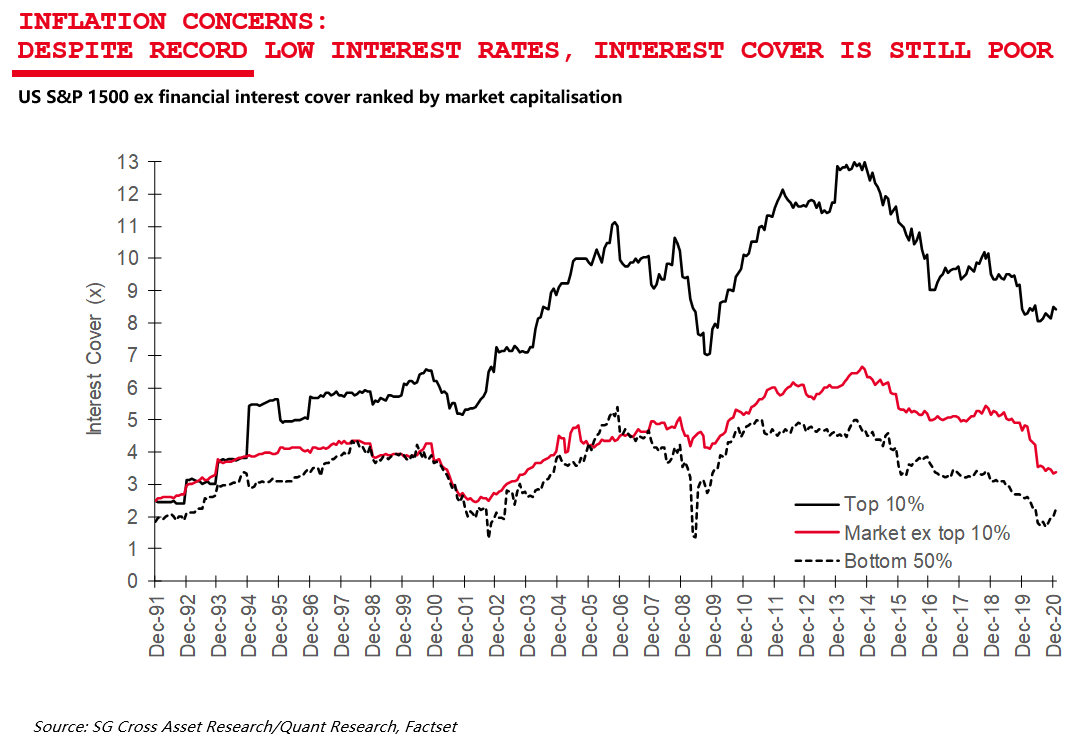

An Eternal DebateAs with guns, so with equity derivatives. Two mass shootings this month have brought back the eternal American issue over how to limit gunshot deaths while maintaining the Second Amendment's promise not to infringe the right to bear arms. And in the markets, another accident, in which a big investor called Archegos Capital Management is imploding after using derivatives to obscure how much risk it was taking in just a few stocks, brings back the issue of how to control financial innovation while maintaining a free market. Thankfully, the market issue isn't one of life and death. But it can be subject to the same kind of unhelpfully zero-sum thinking. Just as guns don't kill people, but the people who fire them, it is just as possible to say that derivatives don't cause financial crashes, the people who misuse them do. Used sensibly, both can make us safer. But in both cases their mere presence raises the stakes, and the risks. Credit derivatives started out as banks attempted to manage their risks more effectively. A lender to General Motors could swap some of its exposure for another's to Ford, for example. But having started as a vehicle for managing risk, they were steadily co-opted to help in taking on more. Now, much the same thing seems to have happened with total return swaps, which make it easier to handle the paperwork between an investor and a bank that take opposing positions on a stock. Rather than go through the hassle of lending the shares to an investor, which then has to sell in order to put on a short position, the bank can instead agree to a swap, with whoever would have lost on the trade paying money at the end to the counterparty. The mechanisms are explained here. The problem is that such swaps can be used to take on massive exposures, which would have to be disclosed to regulators if they were made by conventional means. Tightening of the regulations covering prime brokers — effectively the large institutions that operate as hedge funds' bankers, executing trades for them — mean that only a few now work as counterparties in such deals. This meant that the emerging new system of regulation put the onus on a few large and well capitalized banks to keep count. If they mess up, they may face losses. That appears to be what has happened in the case of Archegos. Various U.S. media stocks and Chinese web companies have seen their stocks tumble as the company desperately tried to meet a margin call — a demand from counterparties for payment after its trades started to go bad. Several big investment banks, led by Credit Suisse Group AG and Nomura Holdings Inc. but also including Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs Group Inc., had to make huge block trades to get Archegos out of its positions, and lost money. Although they were effectively policing Archegos, they were also competing with each other. You can find all the details elsewhere on Bloomberg.com. Should it have been obvious that there was a problem? Yes. The behavior of ViacomCBS Inc.'s stock made no sense when compared with the rest of the market. It's easy to see how its sudden reversal triggered a margin call:  For another example, this is how a popular exchange-traded fund tracking Chinese internet stocks did, compared to a similar ETF for U.S. web stocks. They tracked each other almost perfectly until the Chinese stocks suddenly went into overdrive and then freefall. Remarkably, it was only on Monday that the Chinese web ETF dropped below its 200-day moving average, despite a fall of almost 30%:  These moves show that something odd was afoot. The question now is whether the implosion at Archegos will have knock-on effects. It could do this by creating equity losses at other funds that force them to make adjustments. Or, more damagingly, it could radiate out through the problems created for the banks who lent to them. By the close of trading Monday, it looked as though major contagion had been avoided. It is always possible that more losses will pop up in unexpected places. But unless you're invested in Archegos itself, or you're a shareholder in Nomura or Credit Suisse, it looks as though this hasn't been too painful. That doesn't mean that the system has worked perfectly, or that no change is necessary. In its essence, this drama has played out many times before, and it's infuriating that it's happening again. Anyone who has read Roger Lowenstein's When Genius Failed, his classic narrative of the implosion of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, in what turned out to be a rehearsal for the global financial crisis a decade later, will recognize all the elements. A fund had more exposure than people realized, because it had more leverage than they realized. When the trades went wrong, it had no choice but to sell, forcing down those securities, and threatening the banks that had lent them money. Any number of investors ran into similar problems in 2007 and 2008, when synthetic collateralized debt obligations, and other mind-bendingly complex instruments, allowed many different people to bet with borrowed money that the same package of low-quality mortgages wouldn't default. Regulators had been worried about credit derivatives, but fatefully didn't take decisive action. The last few months have brought us the " Nasdaq Whale," when Softbank Group Corp. of Japan plunged into single-stock call options, and the Gamestop Corp. incident, when retail investors used options in a successful bid to embarrass hedge funds that had taken out short positions in the stock. Now there is Archegos. None of these events has been big enough to turn into a systemic crisis. It would be unwise to wait for one before acting. There is no need to ban derivatives. They can manage risk. And it's fair enough for bankers, who will make a lot of money if they get their bets right, to absorb the losses if they get their risk management wrong. But greater transparency would make it easier for everyone to do their job. If, as appears to be the case, Archegos bought far greater stakes in Viacom and the others than is allowed without triggering corporate governance rules and disclosure requirements, then everyone has an interest in making sure that nobody can do this again. To return to the gun analogy; it makes the market no less free if there are a few clear rules that are well enforced. As the real villain is the person who fired the gun, it would be good if any miscreants in the case were to face trial. And while arming everyone, so that someone shoots back when a miscreant opens fire, is one way to try to contain the problem of criminality, it still makes sense to take reasonable measures to make sure nobody misuses guns in the first place. The rotation within the stock market continues. Possibly helped by the unwinding of the Archegos trades, the "momentum" factor — capturing stocks that are already rising on the assumption they will continue to do so — has taken another beating, while "value" — stocks that look cheap compared to their fundamentals — is rallying further. By Bloomberg's measurement, pure value is having its strongest performance relative to momentum since 2018. A brief rebound for big tech stocks earlier this month has been canceled out:  Value has been underperforming for a long time, and is gaining strength now on the back of a belief in another rotation, into economic reflation, or even inflation. In general, when growth is less scarce, then growth companies — bought for their expanding profits — are less exciting. It is at such points that bargain stocks outperform. The problem may now be that value companies are being bought as though they are completely interchangeable with stocks that do well in conditions of high inflation. They aren't. In the following graph, Andrew Lapthorne, chief quantitative strategist of Societe Generale SA, compares his "inflation" basket of global stocks, mostly from the resources sector, that will do best during periods of inflation, with the Russell 2000 Value index, which covers U.S. small-caps that look cheap. There are no stocks that are in both, and yet their performance has been identical over the last six months as money has poured into small-cap value ETFs:  To look at the same phenomenon another way, one line in the following chart shows the Solactive Global Copper Mines index (as sensitive to rises in commodity prices as just about any companies on Earth) relative to the MSCI All-World index, and the other the Russell 2000 Value. The performance has been almost identical:  The problem, as Lapthorne points out, is that not all value stocks will prosper under inflation, which implies higher long-term interest rates. That would be good news for banks, which also show up on value indexes. But it would be rotten news for companies with weak balance sheets and heavy debt loads. The rally of the last 12 months has in many ways been a "dash for trash," in which companies with weak balance sheets did better as fears of a widespread bankruptcy crisis receded. Another way to capture this is through the "quality" factor, which has various definitions but which generally refers to stocks with clean balance sheets and reliable profitability. Such stocks did predictably well during the Covid scare a year ago, and have performed shockingly badly since then, as illustrated by this chart from Mike Wilson, U.S. equity strategist at Morgan Stanley:  High-quality stocks now look extremely cheap compared to low-quality stocks, then. Wilson also compares quality stocks to the U.S. market as a whole going back to 1984, and reveals that the virtues of a strong and stable company have never been less in demand:  The GameStop excitement highlighted this behavior. If inflation does begin to make itself felt, there is reason to expect this pattern to change. Higher inflation means bigger interest payments on debt. Low-quality companies may be in particular danger because the desperation measures of the last 12 months have resulted in bankruptcies running below the level that might normally be expected — a phenomenon the Bank for International Settlements last week described as the "bankruptcy gap." As the following chart shows, bankruptcies usually move in line with unemployment, and have an inverse relationship with GDP. Last year, that relationship was dramatically upended:  It's easy to explain why. As the BIS shows, credit has flowed to loss-making companies over the last year, to a far greater extent than during the 2007-09 crisis. And the companies most affected by Covid-19, which have tended to do well recently, naturally received the most largesse:  As a result, interest cover for smaller companies looks barely better than at the worst points of the last two bear markets, as this chart from Lapthorne of SocGen shows:  It makes sense for trashy stocks to do well when politicians have made sure that nobody goes bankrupt. But it might be unwise to reckon on that environment continuing. And it looks downright foolish to use poor-quality stocks as a bet on inflation, when their risk of going bankrupt is likely to shoot up in this event. The MSCI Quality index has begun to rebound in the last few days. It is possible that a rotation away from low quality is beginning:  It might still be early. We need inflation to actually rear its head first. People also need a reason to focus on boring companies. The conditions aren't propitious. As Christopher Smart, chief global strategist for Barings puts it, "I don't see quality doing well until the value wave begins to withdraw. And I don't see that happening with stimulus checks going out and an infrastructure agenda on the way. You'd be fighting momentum, and you'd be fighting the president." When the tax rises needed to pay for this come into view, and the market doesn't like them, he suggests, it could be time to switch to quality. That could be many months yet. Survival TipsI've made this tip before, but the family re-watched Hamilton on Disney+ tonight — a live Broadway performance with the original cast, beautifully shot. Every time we watch it there's something more. And somehow it gets more exciting every time. As this is a financial newsletter try Cabinet Battle #1, in which Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson debate whether to set up a system of national debt and a bond market (Jefferson thought the mere idea of a secondary market in bonds was immoral), and The Room Where It Happens, in which Hamilton thrashes out a deal with the Virginians Jefferson and James Madison, getting his financial system in return for putting the national capital on the Potomac. It was one of the most enduring and consequential compromises ever made; and it makes for a great song.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment