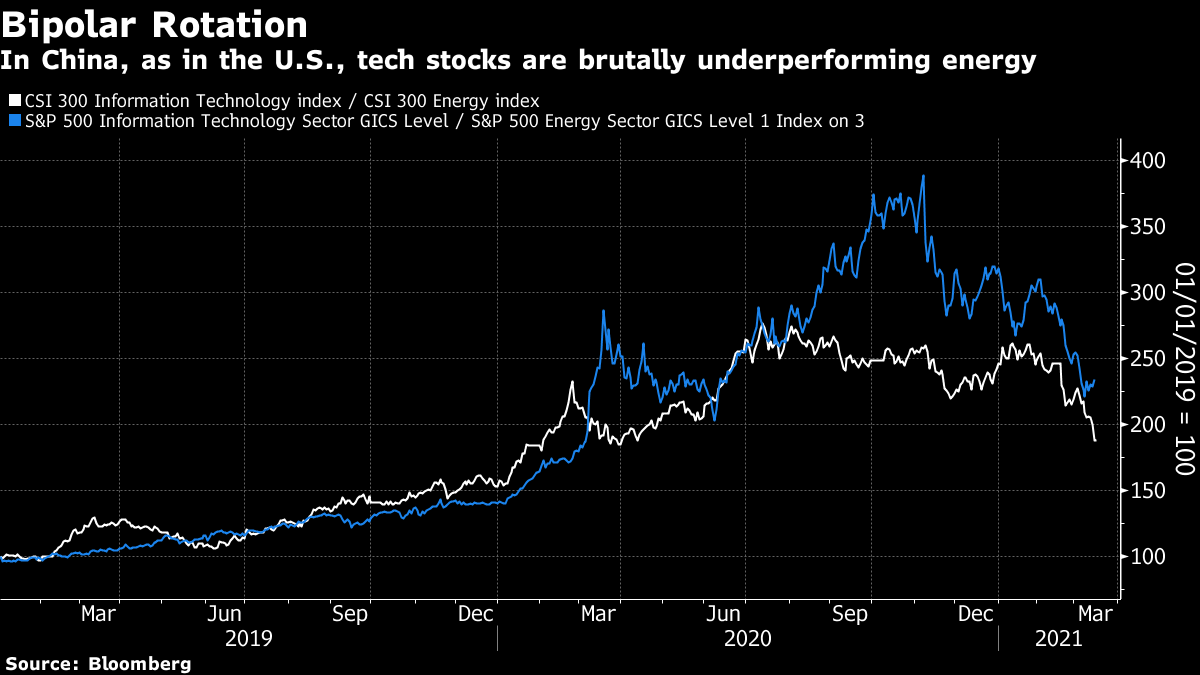

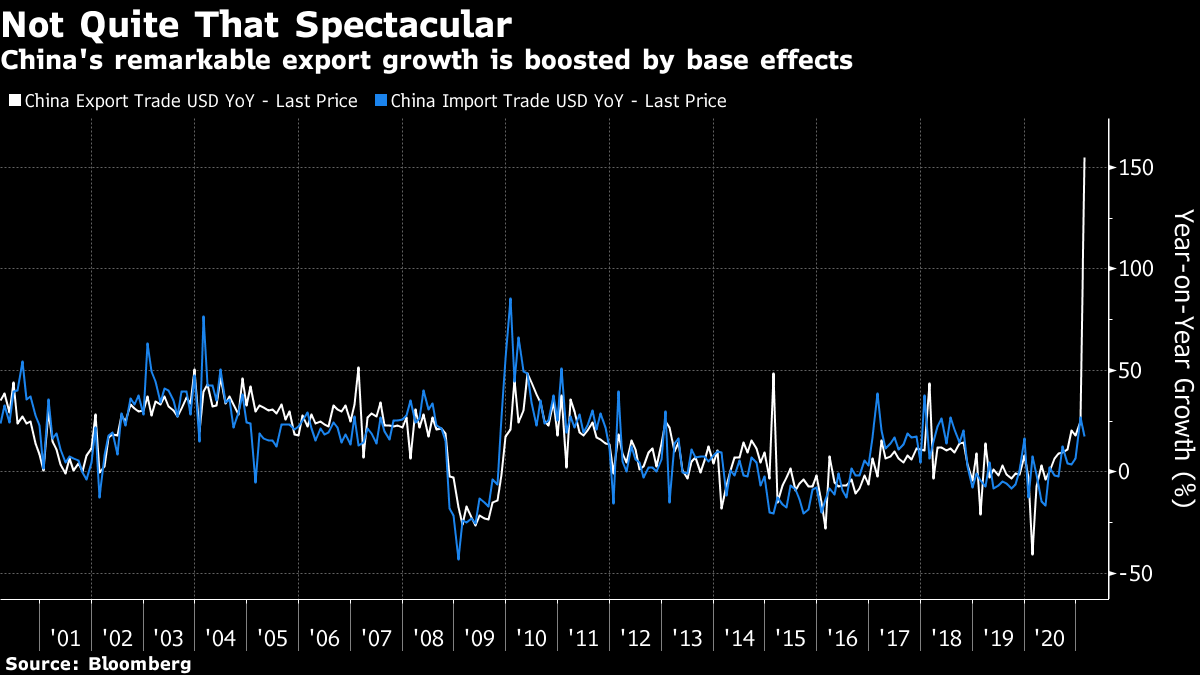

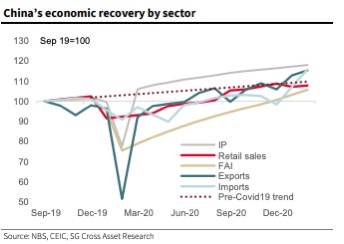

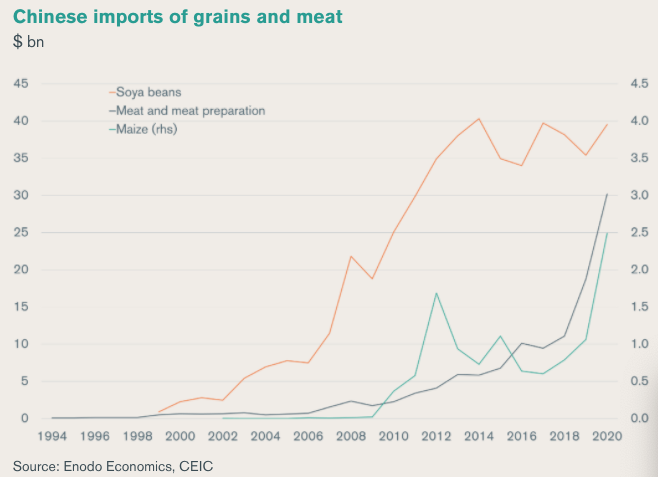

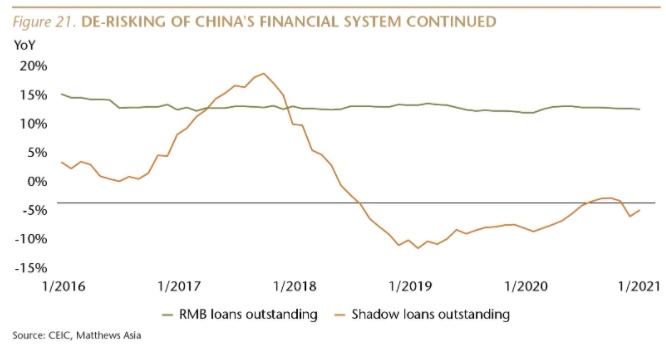

| Chinese stocks are offering another painful dilemma. Like many other aspects of China's economy, the government has much influence over the equity market. Unlike other parts of the economy, however, the government doesn't have the power to micro-manage. Its interventions tend to be ham-fisted, giving the domestic market two bubbles this century — in 2007 and 2015 — both of which burst. The Chinese stock market does send some signals about what the government wishes, though these are imperfect. It also gives indicators — again less than flawless — about the economy and corporate China. What, then, to make of the tumble that Chinese stocks have taken in the last month? The CSI 300 index, which includes the largest A-shares quoted in the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, has dropped 13% since its peak. Meanwhile, MSCI's China index, which includes companies quoted in Hong Kong and the U.S., has fallen sharply relative to both the developed world and the rest of emerging markets. It has done so despite a strengthening Chinese currency:  uo Some of this can be attributed to the same factors that are roiling markets in the West. Technology companies have a heavy presence in China. They've led the market up, and now they are leading it down. The pattern of relative performance of tech and energy companies is similar to the U.S. — although American tech companies did better on the way up:  Beyond that, there are the economic data. China reported a raft of new numbers this week, and at first glance they were spectacular. The figures for export growth are particularly eye-catching:  But this is where we need to be careful. Chinese data are always noisy at this time of year due to the impact of the lunar new year holiday, which can shift between January and February. Add to this the effect of China's pandemic-related shutdown at the beginning of last year, which had a dreadful effect on the export trade, and a massive year-on-year improvement isn't surprising. Compared to forecasts, as measured by the Citigroup economic surprise indexes in which any figure below 0 indicates a disappointment, China's macroeconomic data are undershooting so far this year:  Digging deeper, the following figures from Societe Generale SA's cross asset research team show that China's retail sales recovery hasn't brought it back to its pre-Covid trend, while fixed-asset investment, long thought of as the fuel of the economy, are also below trend. The recovery is instead relying on improvements in trade and industrial production:  Continued local shutdowns to combat fresh Covid outbreaks help to explain the underperformance in retail sales, and also why many domestic-facing companies are disappointing investors. As ever in China, government actions might be more important. There is every sign that authorities are clamping down on some of the most famous names in the private sector, with Tencent Holdings Ltd. shedding $62 billion in market cap in a matter of days as its finance business comes into the focus of regulators, like Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.'s Ant Group before it. Tencent is also one of the big Chinese companies to fall foul of an aggressive new antitrust push. Such regulatory actions will always attract the suspicion that authorities are trying merely to cut the most powerful business executives down to size, and act as an uncomfortable reminder to potential investors that the government can intervene very easily if it wants to. Beyond that, this year's National People's Congress, which ended last week, concluded with rather underwhelming aims for stable growth and maintaining employment. These might be sensible ideas, but they don't inspire excitement among investors who might have been hoping for another binge of credit-driven investment. Instead, the focus now seems more defensive. For example, there was stress on food security and a plan to increase agricultural production. As this chart from Enodo Economics shows, Chinese imports of a range of foodstuffs have risen very fast in recent years. This has had effects on global markets for agricultural commodities, and creates concerns about Chinese security:  Beyond food security, China is anxious to avoid over-extending credit, guided by the terrifying example of the global financial crisis in 2008. After another aggressive credit expansion last year to steer the economy through the Covid shutdown, China's authorities seem to be reining in credit. Again, this may well be enlightened policy for the long-term future of China and the world, but it makes the country a much less exciting investment prospect in the shorter term. For exhaustive coverage of the bullish case for the Chinese economy, try this report by Andy Rothman of Matthews Asia. It includes this chart to show how growth in "shadow loans" outstanding has been controlled since the last dose of expansion in 2016 and 2017:  It's difficult to come to a dispassionate view of China. The nation is guilty of some horrible human rights violations, and appears to be on course for conflict with the West on a number of fronts. This rightly will put the country off limits for some investors. Its behavior in Hong Kong, and the discord over Taiwan add to the sense of a newly assertive power; Max Hastings even argued in Bloomberg Opinion that China's attitude to Taiwan was similar to the U.S. attitude to Cuba in 1963. But the nation's economic success since Tiananmen in 1989 is impossible to deny, and has required brilliant and enlightened planning to go along with what many regard as dirty tricks. Its current actions seem geared toward avoiding any risk of a Chinese "Lehman moment," and for this we can be grateful. A disorderly crash for China would help nobody. One downside of this, however, is that the nation's equities become a less attractive investment. Diana Choyleva, who runs Enodo Economics in London and is a long-time China-watcher, casts all of President Xi Jinping's policies in terms of safeguarding security: in renewing efforts to reduce China's debt burden, Xi wants to defuse the threat of financial instability. In pushing policies to increase food and energy security and to become a high-tech leader, Xi wants to reduce China's vulnerability to supply chain disruptions now that the global political climate has turned decidedly hostile to China. Whether this is a strategy that revives China's feeble productivity growth and brings down leverage remains to be seen. But as a political strategy to achieve Xi's China dream of national rejuvenation, it is hard to quibble with his priorities.

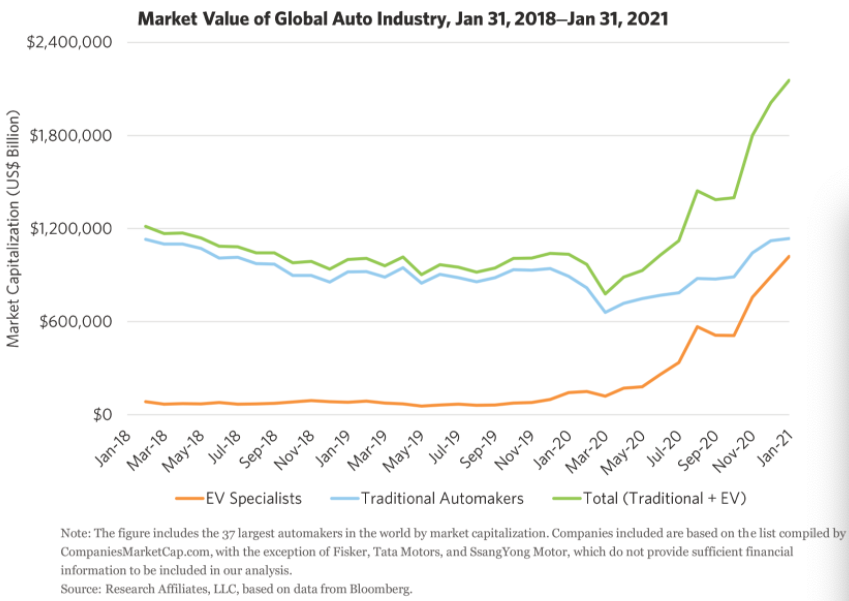

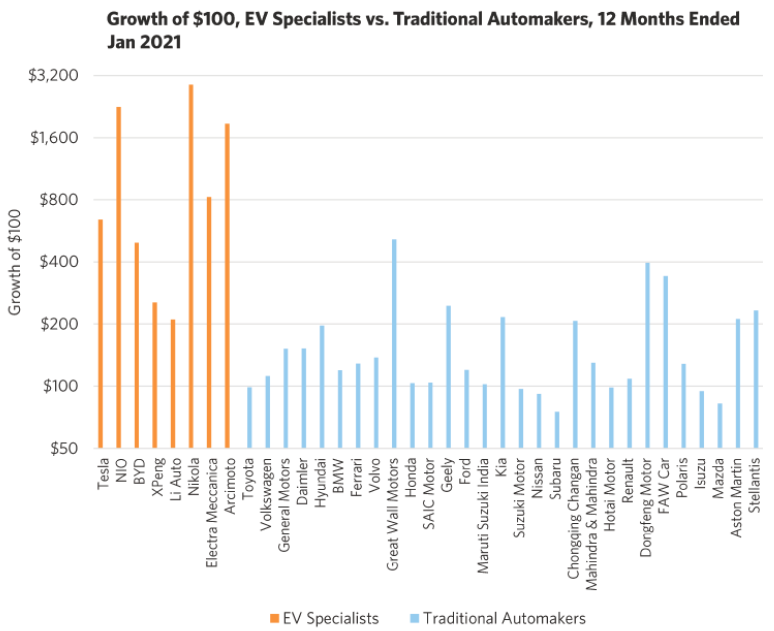

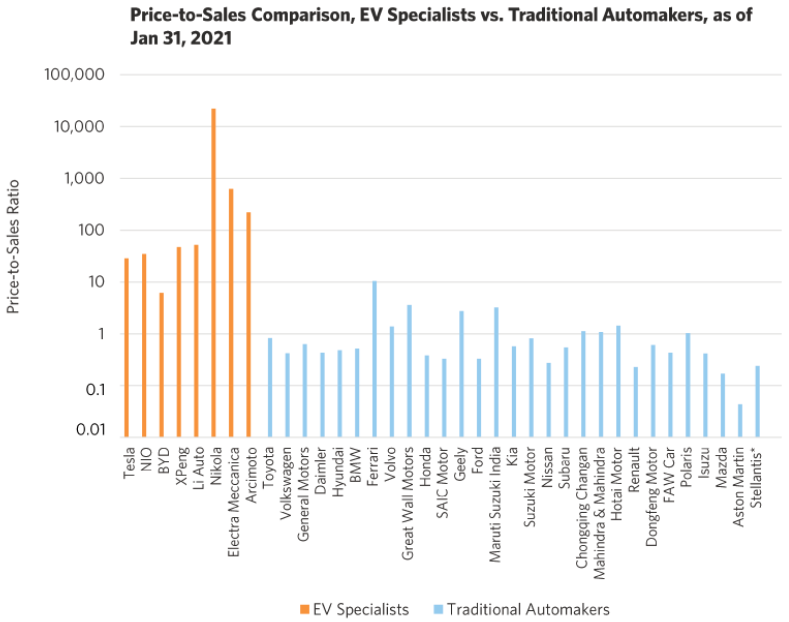

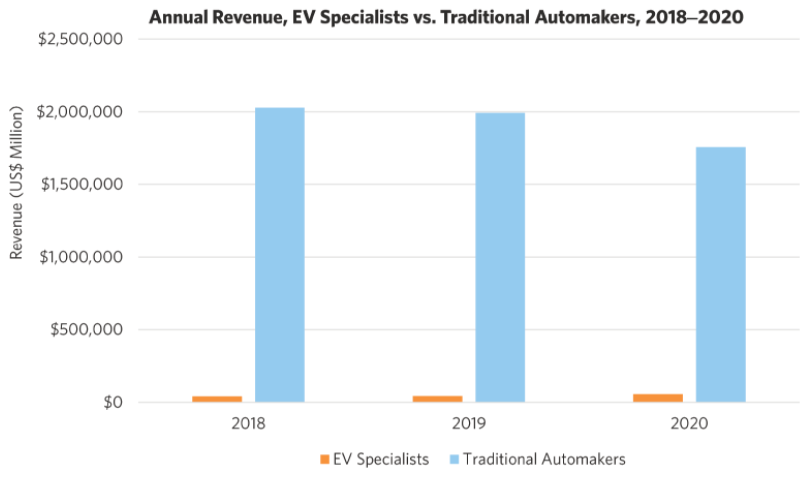

That seems about right. For those who decide that it is morally acceptable to invest in China, the good news is that the administration wants to avert an all-out crash in equities and probably has the power to do so; but the bad news is that its current priorities probably mean its equities will do nothing exciting for a while. Make your decision accordingly. Elon and the Big Market DelusionEven if all the hopes for self-driving electric vehicles are justified, there's still something profoundly wrong with the way Tesla Inc. and the other big EV-makers are being valued. You could call it the market version of the Archimedes principle — the market needs to take account of the fluid the EVs will displace if they are successful. Alternatively, you could attribute it to what Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates calls the Big Market Delusion in a new paper. The point is that if there are going to be big disruptive winners, there will also be losers. It's always possible to enlarge the pie, but there are limits to how far this can go, and in the case of EVs those limits are quite tight. If I buy an EV in future, it means I will buy one fewer conventional car. That will be the case for the vast majority of EV purchases. Yet the total market value of conventional automakers has risen even as the value of EV-makers has gone to the moon:  The size of the entire industry has roughly doubled in three years (which have included one of the worst recessions in history). Either the market seriously thinks that EVs will double the total demand for cars, or it thinks they will be fantastically more profitable than traditional vehicles, or the market is wrong. Now let's look at the what happened to $100 invested in each of the big names in the industry, over the 12 months ending in January of this year. Note that Arnott needed to use a log scale for this, which isn't a good sign when considering returns over only one year.  Tesla, despite its rise to be the fifth most valuable company in the U.S., shows up as having unremarkable performance compared to some EV peers. And plenty of conventional manufacturers had a great year, despite their imminent annihilation at the hands of battery-operated cars. Arnott turns his attention to valuations and again needs to use a log scale. Some great conventional manufacturers, including Toyota Motor Corp., Volkswagen AG and General Motors Co., sell for less than a year's sales. Meanwhile, the EV-manufacturer Nikola Corp. sells for 10,000 times revenue:  The reason for this immense gap is that EV-makers still aren't making much in the way of sales. That includes Tesla. Last year's global slump saw a sharp decline in revenue for the traditional sector and a barely discernible increase for electric cars.  EV-makers clearly should trade for a higher multiple. Their growth lies in the future, but it makes sense to pay for that now, if we can predict it with confidence. Much of the excitement around Tesla is that it has already built up an insuperable first-mover advantage, or in Warren Buffett's phrase it has dug itself a wide economic moat. The steps it has already taken, along with its many patents and advanced technology, give the company a great chance to dominate the new world of EVs, according to its backers. That seems a reasonable contention. The problem is that all of Tesla's EV rivals are priced to do the same. The bottom line is that the most enthusiastic backers of EVs can be completely right (just as those predicting the internet would change our lives 20 years ago were right), and yet the market can still have it totally wrong. Arnott offers airlines, an exciting industry that proved to have no barriers to entry as an example. Dot-coms were another; you were sure one online retailer would make it big, but didn't know which, so you bought them all. This would have been fine, except they were all priced as though they would be the ultimate winner. For another way of looking at it, try this league table of the 30 largest stocks in the S&P 500 Information Technology sector as of 21 years ago, right at the top of the bubble. I chose 30 because Apple Inc. was in 30th.  Someone very clever might just have worked out in 2000, before the dawn of the iPod, that Apple would rise to the top. But in doing so it destroyed the business models of many other companies. This is the same list today:  If EVs take off as tech did, it's a fair bet that the existing league table of companies will be scrambled over the next 21 years. Best to acknowledge this and avoid the fallacy of big markets. Survival TipsIf you need to retreat to a trance-like state (and many of us do), you might try this: Northern Lights by the Norwegian composer Ola Gjeilo, which you can listen to while watching a murmuration of starlings at the wildfowl reserve at Otmoor, near Oxford. The combination has the power to soothe. Or more accessibly, but also from Norway, you could try Runaway by Aurora — written at the age of 11, with a video recorded when she looked little older than that. She has since, I learn, been discovered enough to collaborate on a Disney soundtrack and to inspire Billie Eilish. And she certainly has talent. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment