Sage WordsAfter an extraordinary week in the bond market, a familiar oracular voice from Omaha, Nebraska, reminded everyone of just how extreme that bond market had become. Warren Buffett, still CEO of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. at the age of 90, published his annual letter to investors. You can read it here, and my colleague Tara Lachapelle's commentary on it here. Some will be disappointed that he didn't take the time to inveigh against GameStopmania, or to tell us whether he thought the stock market was in a bubble. But in a discussion of the business model of his vast network of insurance businesses, he offered this gem on bonds: [B]onds are not the place to be these days. Can you believe that the income recently available from a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond – the yield was 0.93% at yearend – had fallen 94% from the 15.8% yield available in September 1981? In certain large and important countries, such as Germany and Japan, investors earn a negative return on trillions of dollars of sovereign debt. Fixed-income investors worldwide – whether pension funds, insurance companies or retirees – face a bleak future.

Some insurers, as well as other bond investors, may try to juice the pathetic returns now available by shifting their purchases to obligations backed by shaky borrowers. Risky loans, however, are not the answer to inadequate interest rates. Three decades ago, the once-mighty savings and loan industry destroyed itself, partly by ignoring that maxim.

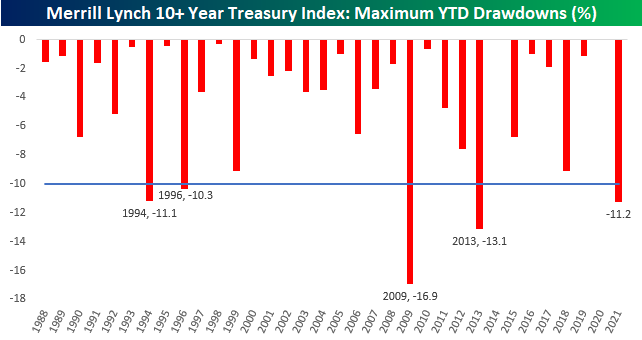

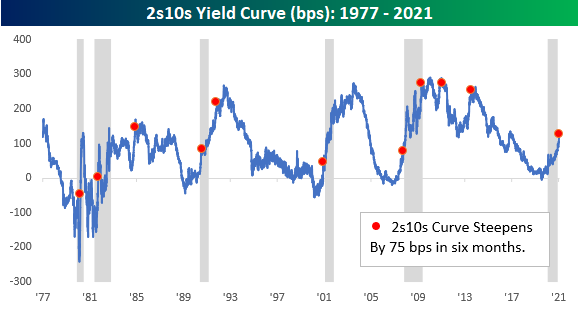

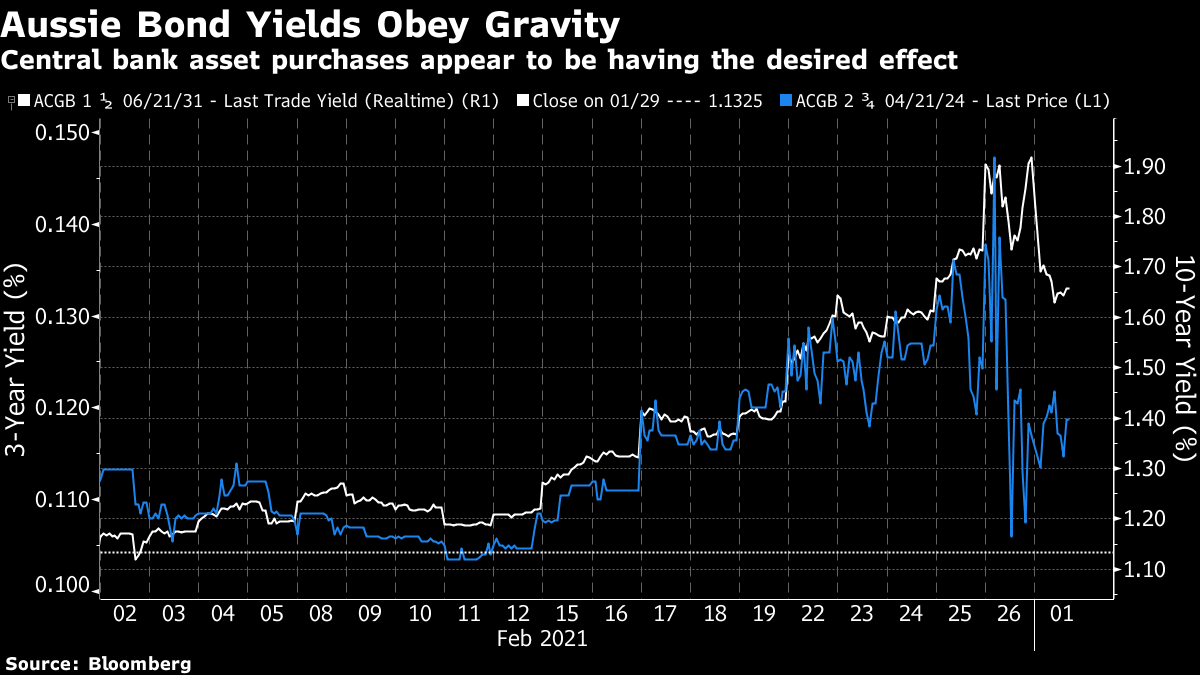

That puts the bond market ructions into all the perspective we need, if not too much perspective. Stocks are, by almost any measure, cheap relative to bonds. But that is primarily because bonds have become so expensive. Bonds are at a high risk of selling off unless someone goes to great lengths to prop them up (probably through central bank asset purchases, or government regulations that force institutions to buy them). Bond market sell-offs on the scale witnessed in the first two months of 2021 are very unusual, but this one shouldn't have been that surprising given the extreme valuation that bonds had reached. Bespoke Investment handily produced this chart, of the maximum drawdowns seen in each calendar year since 1988. Just by the end of February, this already ranks as the third worst year for bonds in that time:  How much further could this go? Another measure of how much the bond market is braced for reflation is the steepness of the yield curve. The more the 10-year yield rises relative to the two-year, the more the market has shifted toward a belief in reflation. An upward shift of 75 basis points within six months, as we have just witnessed, is unusual. Bespoke shows all the previous instances since 1977:  The last three all proved false alarms during the post-crisis period. But all of those came with the curve significantly steeper than it is now, and markets soon realized that their hopes for a reignition of economic growth would go unfulfilled. Past shifts to the current level have generally been followed by an even more precipitous move. But both the last two instances, in 2000 and 2008, came just as a recession was starting and not, as now, when one appears already to be over. So, if the market is right that reflation is with us, and the central banks allow this, 10-year yields could rise further and create an even steeper curve. But the fact that it has taken this long into the economic cycle to move this far suggests that something — presumably last year's intervention by central banks — has already postponed the process by a matter of a year or so. Markets are driven by the intersection of sentiment and reality — and the two often affect each other. So to determine what happens next, I will take a quick look at some measures of both perception and reality. On perception, the market is about as uniformly bullish and certain of the reflation thesis as ever happens. One beautiful indicator of this comes from Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts. He points to this illustration from the New York Times, which appears under a headline that the "Biden economy risks a speeding ticket":  To give an idea of how drastically sentiment has turned, this is an image from Points of Return only six months ago, when I likened the U.S. economy not to a hot-rod, but to a Reliant Robin three-wheel car:  The headline, incidentally, was that the economy "doesn't need a speed limit" because it would be difficult to run hot enough to generate inflation of more than 2%. So maybe that image was a contrarian indicator to bet on the economy to start souping up. It's also worth internalizing that sentiment can change very quickly. Atwater in Financial Insyghts pointed out that the New York Times's hot-rod was almost identical to another that The Economist put on its cover in early 2018, after the Trump administration's big corporate tax cut had been passed:  That proved to be yet another false alarm. Before long, the stock market was swooning at the possibility of higher yields and balance sheet tightening, and the Federal Reserve had to execute a U-turn, over a year before the pandemic hit. The economy wasn't, alas, running hot. And that image may have signaled an extreme in sentiment. Is it possible that another shift in sentiment is coming? Among the economic commentariat, an intriguing change does appear to have started in the last few weeks. There was a widespread view that the Obama administration had been too timid with the stimulus it enacted in early 2009 after the global financial crisis, and that this time the Biden administration should "go big." This undergirds much of the reflation trade excitement of the last two months. But former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, well known for past warnings about the dangers of secular stagnation, has attracted much comment for a piece in the Washington Post in which he pointed out that "whereas the Obama stimulus was about half as large as the output shortfall, the proposed Biden stimulus is three times as large as the projected shortfall." His headline declared that the $1.9 trillion package would bring "big risks." As Summers was part of the Obama economic team in 2009, and said in the piece that he agreed it would have been much better to legislate a "much bigger stimulus" in 2009, this carried a lot of weight. Meanwhile my old colleague and mentor Martin Wolf, also sympathetic to attempts to move toward active fiscal policy in recent years, wrote this in the Financial Times:  The excitement over getting the economy running again is turning into decided nerves about whether a $1.9 trillion stimulus is really a good idea. The plan narrowly passed the House of Representatives over the weekend; we can expect markets to move very actively to every new detail that comes out of the Senate, which could not be more finely balanced. A smaller stimulus might have a sharply dampening effect on the belief that yields should rise to head off an imminent overheating. It is in Congress that sentiment will have its first critical collision with reality. The second will concern central banks. Do they want to keep yields down and yield curves relatively flat? If so, they can probably make it happen. In this area, Australia, an economy that is at much more risk of overheating than most, leads the world. After the country's bond yields spiked, the Reserve Bank of Australia announced new purchases of its target three-year notes last week, and kicked off this week with an announcement that it was stepping up purchases of 10-year securities. The response by yields has been immediate:  Action in Australia could have a big effect on sentiment across the rest of the world. Most important, of course, will be the Fed, which hasn't pushed back against rising yields, even verbally, as strongly as other central banks. If they want to make a point, five separate Fed governors give speeches on Monday, while Chairman Jerome Powell is due to speak on Thursday. The Fed's attitude could move the bond market in either direction, and so Fedspeak is going to be monitored even more closely than usual this week. Meanwhile, we also need to know whether the economy itself is, indeed, reflating. The first day of March will bring the customary month-end data deluge, led by purchasing manager indexes of manufacturing from around the world. China's PMIs are already out, and both the main surveys show a decline from the previous month, and a disappointing overall level. The indexes remain above the level of 50 that signals the border between expansion and contraction, but at this point the Chinese economy looks slightly more like a Reliant Robin than a gleaming hot rod:  We can expect data from the rest of the world to have a further effect on sentiment as Monday continues. Surprisingly strong data elsewhere could spark more sales of bonds and another spike in yields. It is possible that last week saw a peak in the excitement over the reflation trade. It will take much more to confirm that. But having come a long way in a hurry, the market has come to a convenient point to pause and gather evidence before going any further. Survival TipsOne tip for survival is to keep your nose in a good book. My current recommendation is Memoirs of a Stock Operator, the classic written almost a century ago by Edwin Lefevre, about the market adventures of the notorious speculator Jesse Livermore. American readers with a Kindle can pick up a copy for 95 cents, so it shouldn't bankrupt you. You can read it like a novel, it gives plenty of precise technical guidelines on how to play the markets, and if you read it now you get the chance to discuss it on a live blog on the terminal on March 17. We've carefully timed this month's discussion to provide something to occupy the hours before the Federal Open Market Committee announcement that afternoon. Some have suggested that this book club recommendation is a little off the wall, but I suspect the adventures of an intrepid trader a century ago may be as relevant as anything else to guiding us through the current market thickets. Also, unlike some of the books I've selected, it's often laugh-out-loud funny. Please read, with a view to working out what has actually changed in the intervening century, with all its advances in computing power and communications, and what still remains the same. All comments and questions will be gratefully accepted at the book club e-mail address: authersnotes@bloomberg.net. Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment