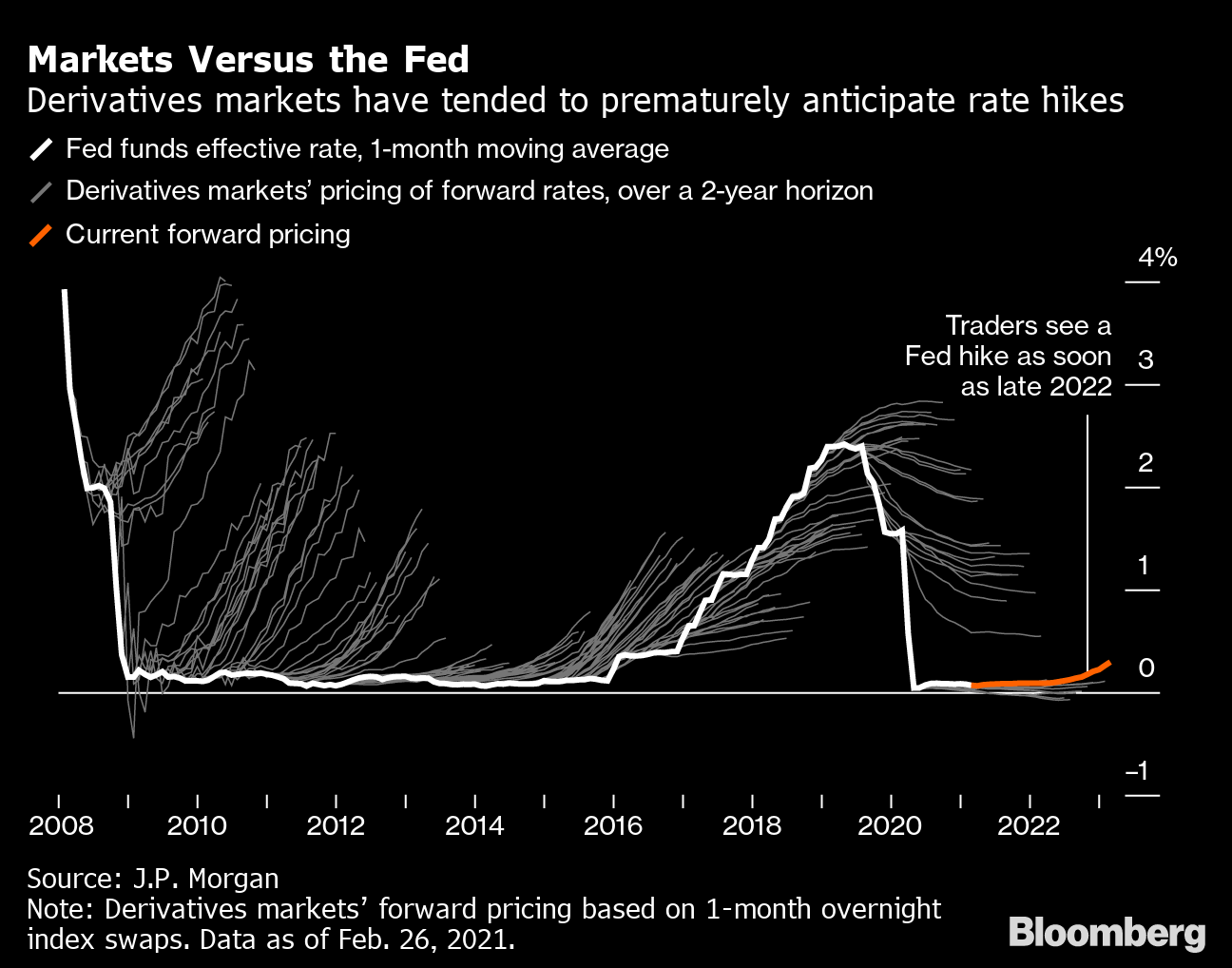

| Suez ship still stuck, chip shortage gets worse, and Biden's new vaccine target. Still stuck The ship that has completely blocked the Suez Canal may not now be moved until at least next Wednesday, according to people familiar with the matter. The longer-than-expected closure of one of the world's most important maritime routes will disrupt global supply chains for everything from grain to cars to coffee. The number of ships loaded with billions of dollars worth of goods waiting to traverse the canal has risen to more than 300, according to Bloomberg data. Chips are downThe global shortage of semiconductors remains in focus after China's Nio Inc. announced it would temporarily halt production at one of its factories due to the chip shortage. The global auto industry was already struggling for supply before last week's fire at a Japanese manufacturer of automotive chips exacerbated the problems. Ford Motor Co., Toyota Motor Corp., Volkswagen AG and Honda Motor Co. all have had production problems due to the shortage. Vaccine target President Joe Biden set a goal of administering 200 million Covid-19 vaccine doses by the end of April, while in Europe, leaders gave cautious backing to a plan to restrict vaccine exports from the region. On a global scale the pandemic is far from over with 733,000 cases reported yesterday, the highest level since mid-January. The number of deaths in Brazil passed 300,000 this week, with the government under increasing pressure. Markets riseMost global equity gauges are higher this morning as investors look past supply chain disruptions and focus on the optimistic targets for vaccinations and economic re-openings. Overnight the MSCI Asia Pacific Index added 1.3% while Japan's Topix index closed 1.5% higher. In Europe the Stoxx 600 Index had gained 0.5% by 5:50 a.m. Eastern Time with miners by far the best performers. S&P 500 futures pointed to a small pop at the open, the 10-year Treasury yield was at 1.655%, oil rose and gold gained. Coming up... Personal income probably plunged more than 7% in February after January's stimulus-check driven 10% surge. Spending likely dropped in the month too, while the PCE deflator may have picked up to 1.6% when the report is published at 8:30 a.m. The March University of Michigan sentiment number is at 10:00 a.m. The Baker Hughes rig count is at 1:00 p.m. What we've been readingHere's what caught our eye over the last 24 hours. And finally, here's what Katie's interested in this morningAs it turns out, bond traders are pretty terrible at timing the Federal Reserve. While that sounds like a diss, it's also the entertaining conclusion of a Bloomberg News article that examined the past 13 years of money-market derivatives. Since 2008, markets have consistently priced in a more aggressive path of Fed rate hikes than what ultimately happened. Consider the situation in late 2008: traders were already bracing for several hikes in the years ahead, according to data crunched by JPMorgan Chase & Co., but policy makers held off on tightening until 2015. Amusingly, that experience then left traders behind the curve when the Fed liftoff really got going. The central bank hiked a total of seven times between the start of 2017 through the end of 2018, leaving traders scrambling to keep up. These history lessons cast a new light on one of the narratives that's emerged from this year's bond selloff -- that the market will somehow force officials into hiking rates earlier than current Fed projections, which have the central bank on hold through 2023. Nearly a quarter-point of tightening late next year was priced into swaps and futures as of Thursday, while three increases of that size were reflected by the end of 2023.  "The market has its pricing and perceptions, and what happens can differ from that and has," Alex Roever, head of U.S. rates strategy at JPMorgan, told Bloomberg News. The market has been testing the Fed by "trying to push further forward the first hike. But Fed officials don't seem to be having any of it." A quick look at U.S. financial conditions helps explain why. Financial conditions are a grab-bag measure of different strains across asset classes, from stocks to credit spreads to sovereign bonds. Notably, they've barely budged, even as long-term borrowing costs shot higher this month and equity markets wobbled. Rather, the Fed's policy stance is still decidedly accommodative. "Overall financing conditions for households are still low and easy. Even though rates have risen, they are coming off a low level. Spreads are still tight. Overall, equities are near all-time highs," said Priya Misra, the head of U.S. rates strategy at TD Securities. "So the Fed's probably looking at that and seeing no reason to get concerned about rising rates." In any case, the bond market is perhaps starting to take Chairman Jerome Powell at his word, which has remained -- throughout four separate speaking engagements this week -- that the Fed won't put away its toolkit until the economy is "all but fully recovered" from the coronavirus shock. Benchmark 10-year Treasury yields have pulled back to about 1.65% from a March high of 1.75%. "As we've repeatedly argued, if markets do give credibility to the Fed's average inflation targeting and maximum employment goals, yields could slide considerably further," Bespoke Investment Group analysts wrote in a note this week. Follow Bloomberg's Katie Greifeld on Twitter at @kgreifeld Like Bloomberg's Five Things? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment