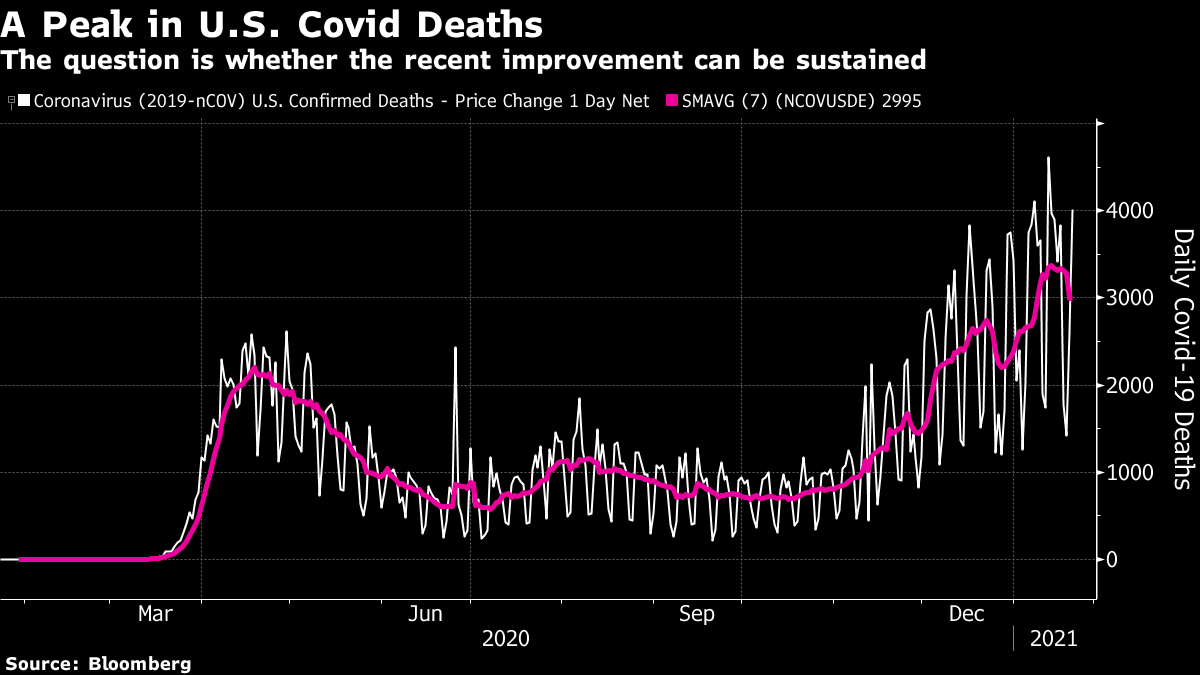

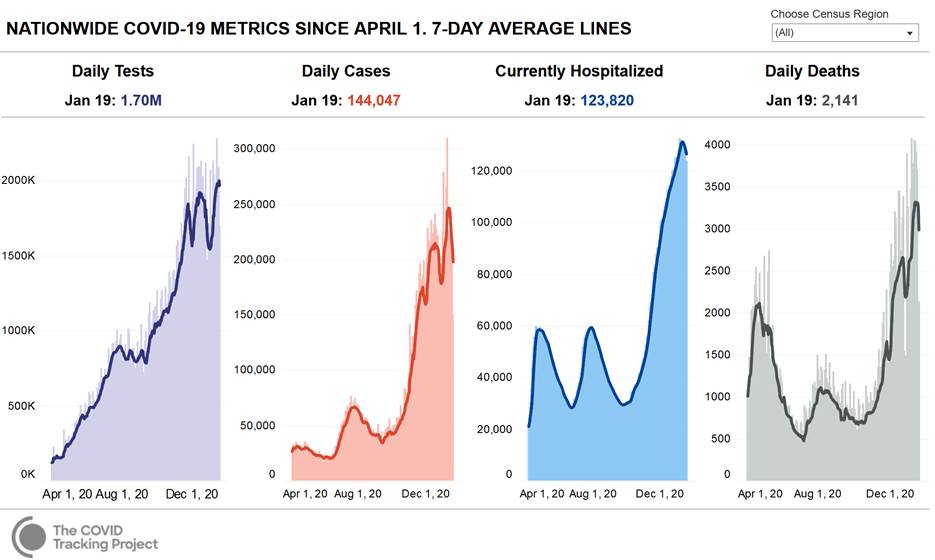

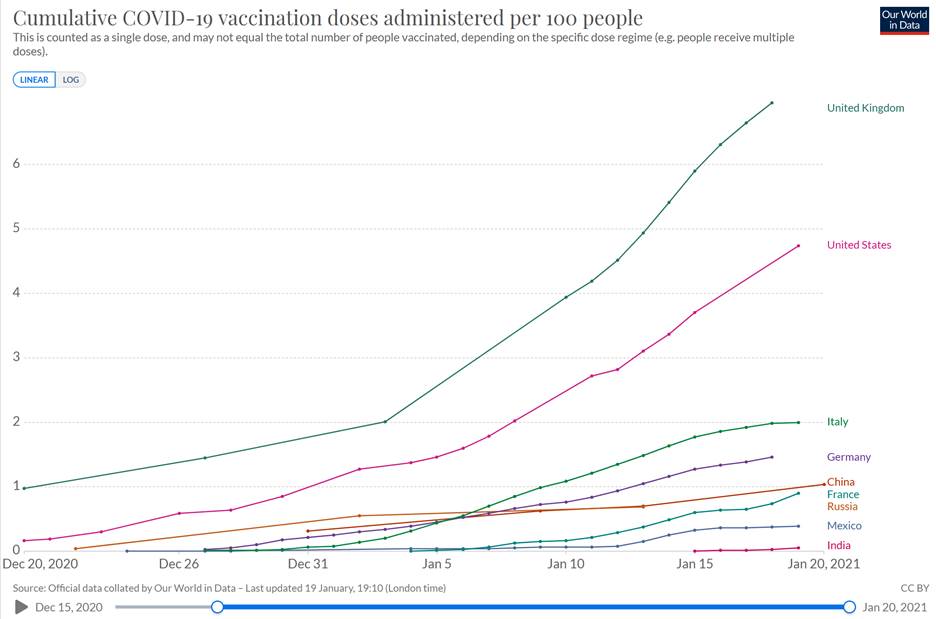

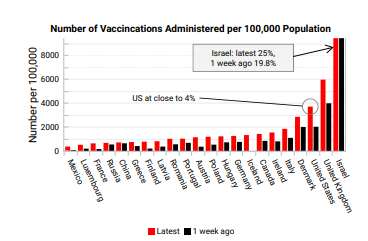

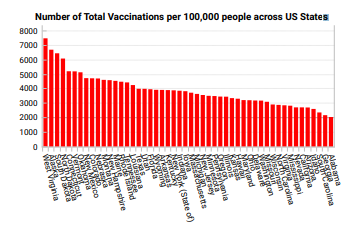

Everyone Agrees: Vaccines MatterNow that America has at last installed its 46th president, on a day thankfully free of surprises, there is an unusually clear moment of alignment. It isn't political; that may remain elusive. Rather, President Biden has a clear task that people of all political persuasions can support, and which could boost the economy and markets in the U.S. and the rest of the world. Succeed, and all kinds of vistas of possibility open up before him. Fail, and he could be a lame duck within months. He has to distribute the vaccines as swiftly and fairly as possible. So much is riding on getting this program right that many financial firms are producing their own models of the likely outcomes and risks. After R-rates and arguments over lockdowns last year, these questions will dominate our personal and professional lives for the next few months (at least). So here is an attempt to summarize the issues. First, deaths reached a new and alarming peak earlier this month, and remain far higher than during the first New York-centric high last spring. But the last few days have seen a slight and hope-inspiring decline:  Broader measures of the U.S. pandemic, produced by the Covid Tracking Project (reprinted in Whitney Tilson's excellent blog) confirm some signs of improvement in a terrible situation over the last few days:  It is unlikely that the vaccine has yet had an effect on these numbers. The first Western patients (including one William Shakespeare) received doses about six weeks ago. Since then, distribution has been very varied across countries, as this chart from Our World in Data, quoted by Tilson, makes clear:  U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson has faced much criticism in recent weeks, and deservedly so, but his government's vaccination record looks great in international terms. Meanwhile progress in the U.S. is much faster than in continental Europe, even though Biden has chosen to raise the stakes for himself by calling the rollout a "dismal failure." Looking at a broader range of countries, in this chart from Variant Perception Ltd., Israel is almost literally off the charts — a legacy of the nation's unfortunately long history of dealing with logistical challenges — while there is a distressingly long tail of those that have barely started the vaccination process:  Within the U.S. the decision of the outgoing administration to leave vaccinations to states shows up in the wide gaps in progress. Politics has little to do with this as both the best (West Virginia, Alaska and the Dakotas) and worst (Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and Idaho) are Republican-controlled:  So there is a logistical problem. If the federal government can bring all states up to vaccination rates like West Virginia's, it could make a swift and profound change to the country. That remains a big "if." Biden is staking a lot on making it happen. How quickly can the U.S., and other countries, vaccinate enough people to bring down deaths, and hospitalizations (thus relieving pressure on health systems and allowing lockdowns to be lifted)? And how quickly can we reach true herd immunity, where the disease can no longer spread? Various economists are trying to model it. Variant uses assumptions borrowed from the U.K.'s Covid-19 Actuaries Response Group: Vaccinations prevent infections, hospitalisations and deaths respectively. We think the assumptions of the ARG are broadly reasonable: the vaccine takes 14 days to protect people; cases take 6 days to show up in the data after someone is infected; it takes another 6 days on average after that for a case to be hospitalised; and another 8 days after that for the most serious cases to die and for that death to be reported. Therefore we assume the mean time of when vaccinees should start to negatively impact cases as 20 days after their shot, with a normal distribution around this day. Similarly 26 days for the effect to show up in hospitalisations, and 34 days for it to show up in hospital deaths.

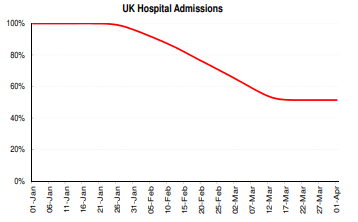

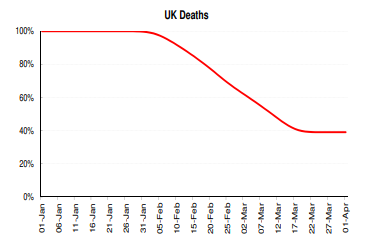

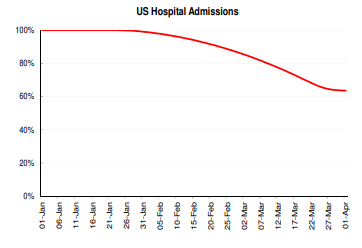

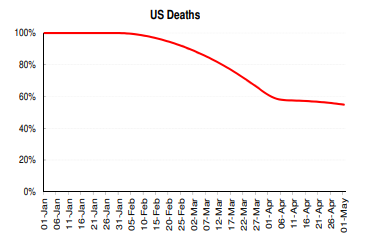

Its models also assume that the most vulnerable are vaccinated first, meaning that the impact is felt on hospital admissions much quicker than on cases in the population. They make conservative assumptions on vaccines' effectiveness, to take account of the fact that those licensed so far have different levels of efficacy. They also assume that there are no lockdowns, or other restrictions on social mobility that would reduce the spread. On this basis, Variant projects the U.K.'s faster start will allow it to cut hospital admissions in half by the middle of March, while bringing deaths down by some 60%:   America's slower start means it won't make such quick progress — although progress on these lines should make many people happier. These are Variant's projections:   Its conclusion for the U.K. is that the peak impact on hospitalizations will have arrived by March, at which point the government can start to ease lockdowns. Why would the U.S. be slower? We see two key reasons that drive this: 1) the UK priority grouping is more granular and targeted so Covid impacts fall quicker relative to the baseline; and 2) the increase in US vaccinations per day (25,000) is too low given the less-targeted nature of the rollout. The ACIP's (a division of the CDC) proposed US vaccination rollout is built at the national level and acknowledges the difficulties of a state-by-state approach. If US states can ramp up vaccinations to the elderly over the next few weeks (exceeding the 25,000 national increase), then a much greater reduction in baseline deaths can be realised, similar to the UK.

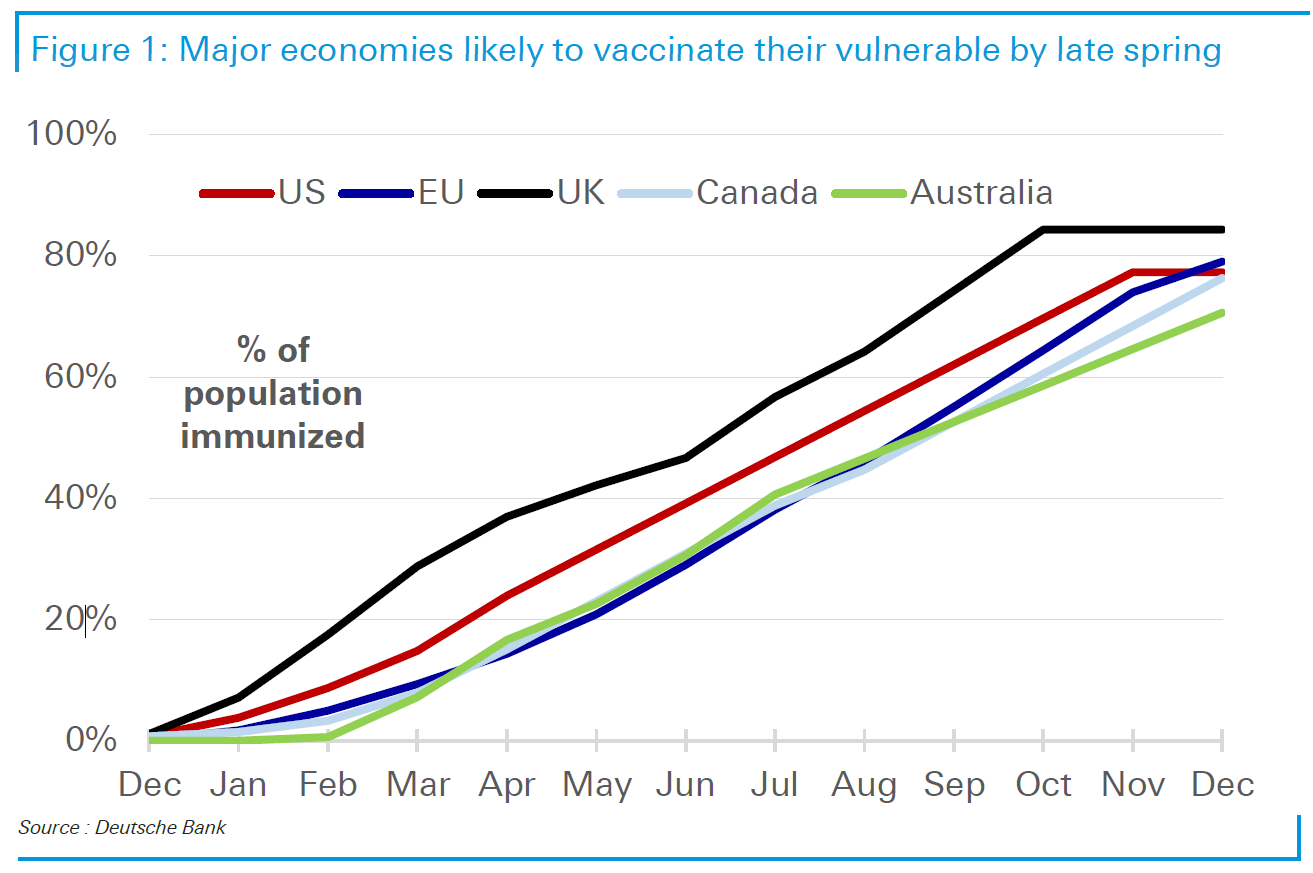

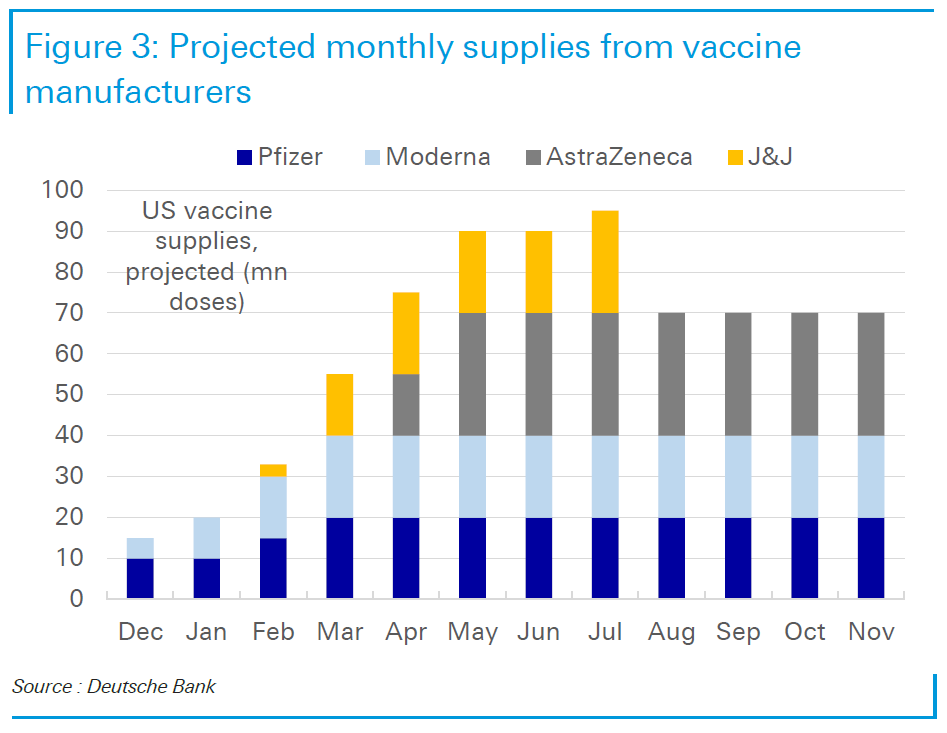

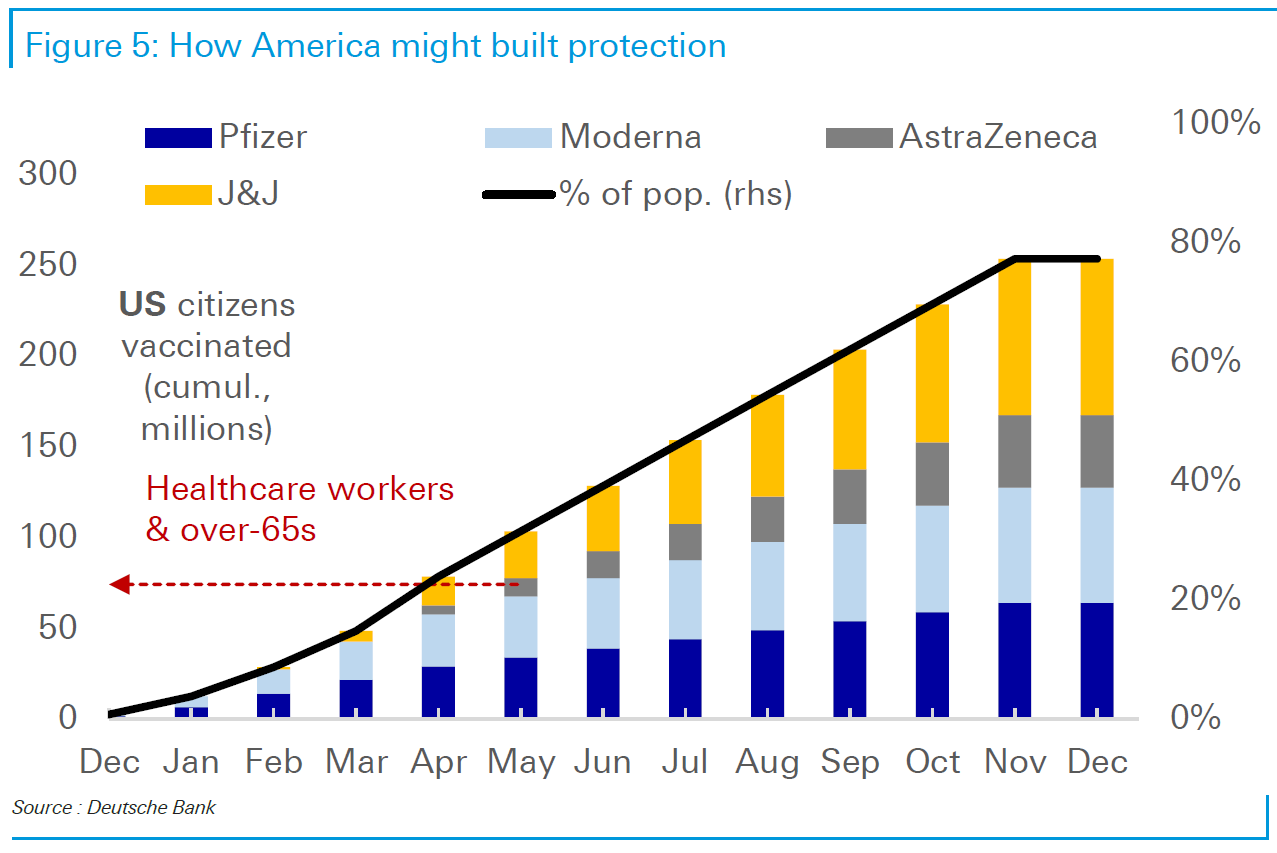

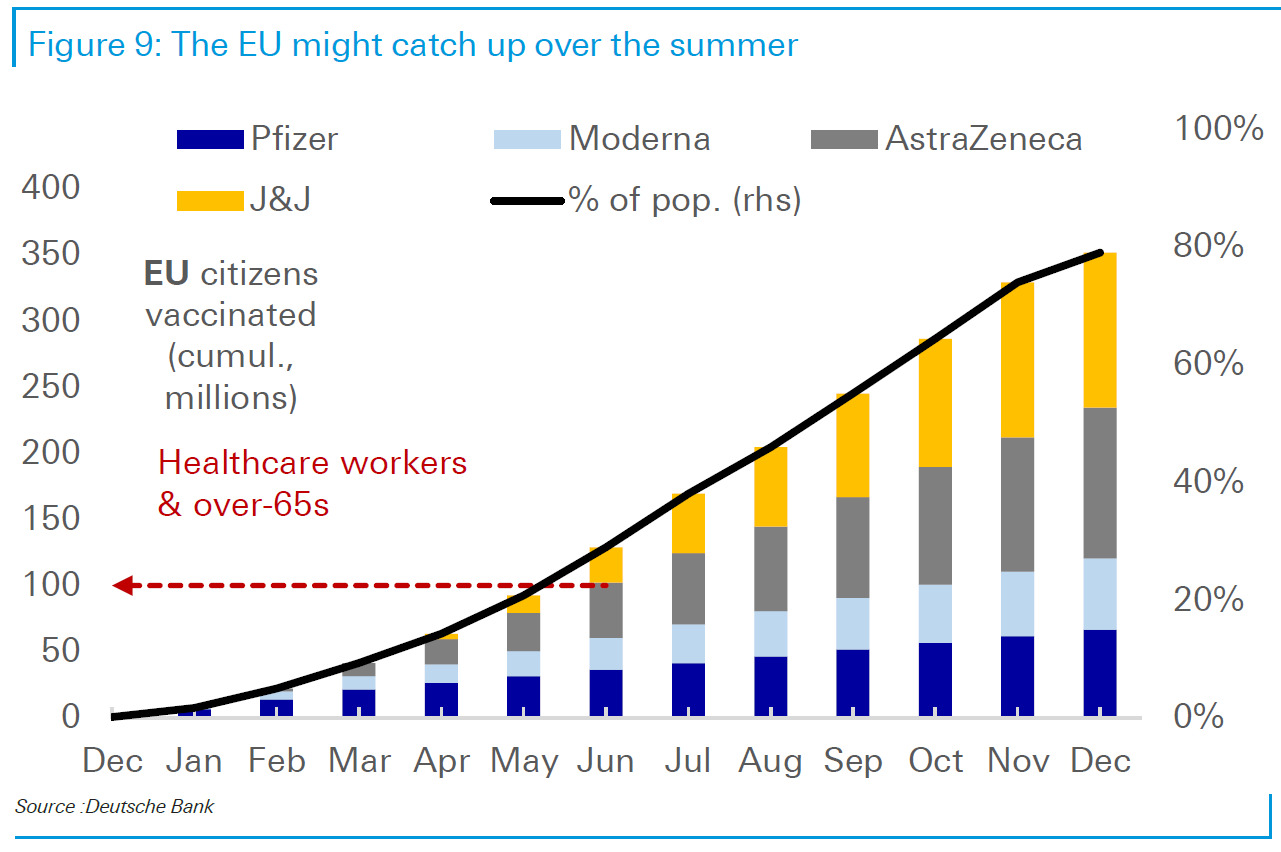

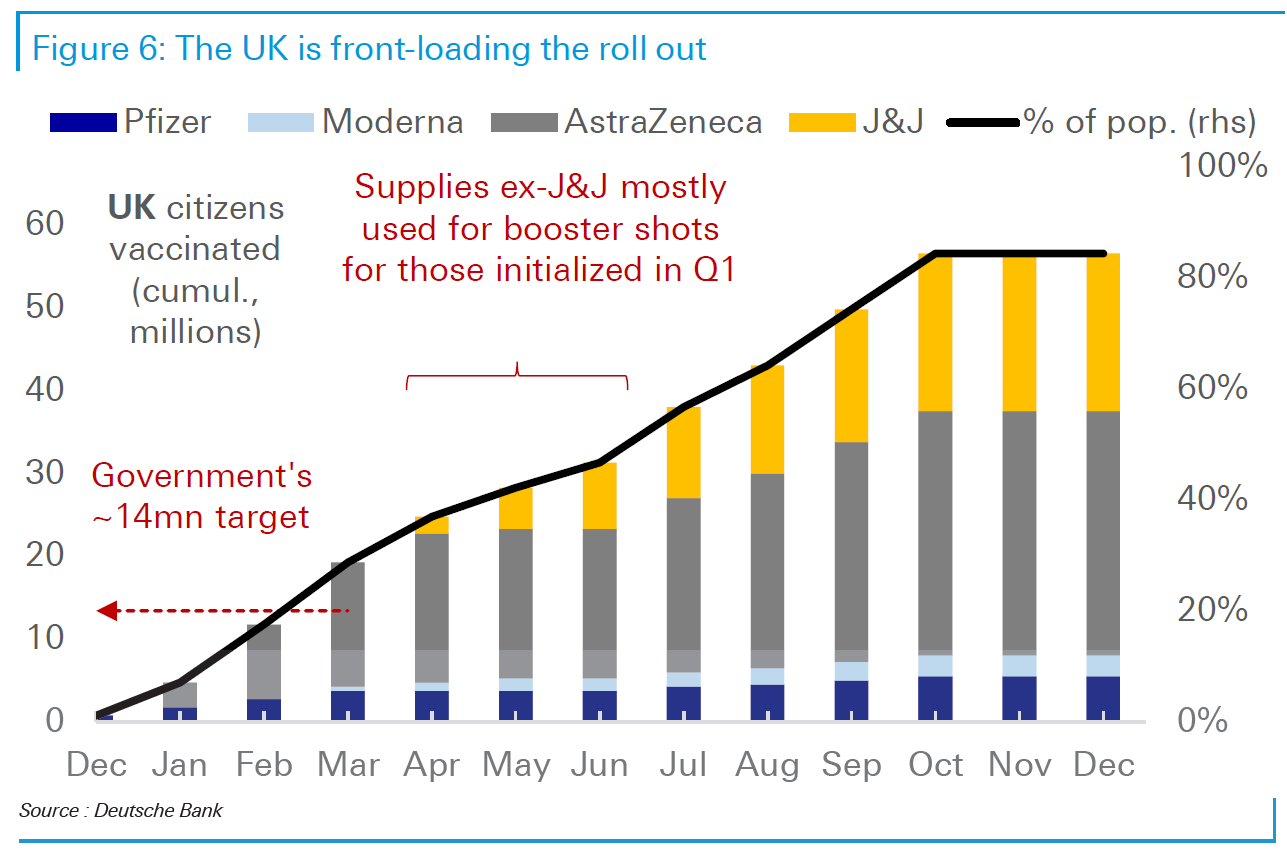

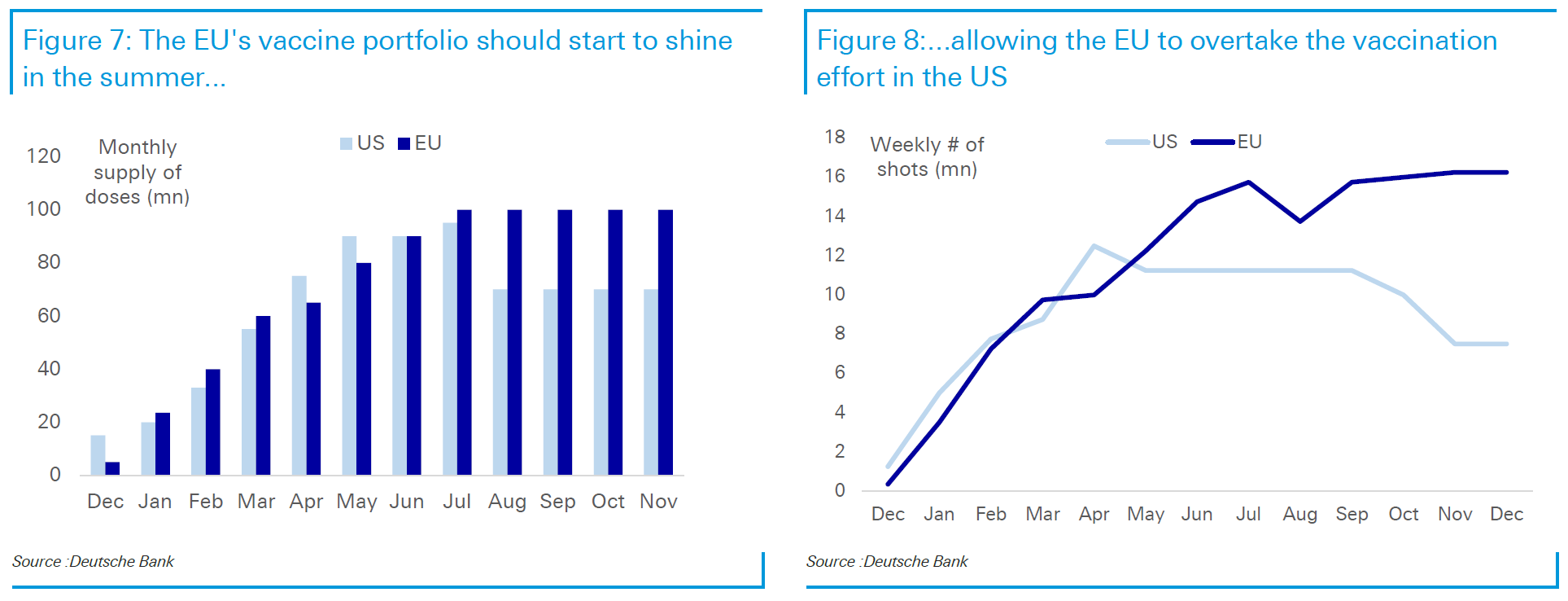

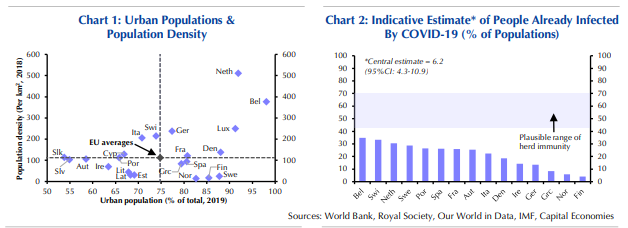

That, in a nutshell, is what Biden needs to deliver. Deutsche Bank AG's Robin Winkler carried out a similar exercise, looking at how quickly each country can be expected to get 80% of its population immunized. His version shows the U.K. maintaining its lead over other Western countries throughout the year, and completing its program before next winter. The EU will lag behind, but might catch the U.S. by the end of the year. All should have completed enough vaccinations to reach herd immunity by year-end.  If this proves roughly correct, it could have a big effect on foreign-exchange markets, where the British pound has been punished for Brexit. If Britain's vaccination fulfills current hopes, that could strengthen sterling. Winkler sees supply of vaccine as a critical constraint. It is here that differences between the treatments begin to show, along with the benefits of "vaccine nationalism" — the scramble by richer nations to order doses in bulk last summer. These are Deutsche Bank's projections for U.S. supply:  By comparison with other countries, the U.S. will have plenty of access to the Moderna Inc. vaccine, but rather less to the one being produced by AstraZeneca Plc and Oxford University. The Moderna and Pfizer Inc. vaccines use similar technology and have efficacy of more than 90%. But both require two doses, and present logistical challenges because they need to be kept at very cold temperatures. This means that in practice they are most easily administered in hospitals. The AstraZeneca and a similar forthcoming vaccine from Johnson & Johnson appear to be somewhat less effective, but have the great advantages that they can be stored in normal refrigerators, and only need one dose. These can more easily be distributed through local doctors' surgeries, or potentially through mass-vaccination sites in gyms and ballrooms. The problem for the U.S. is that it has little access to the AstraZeneca vaccine, so is overly dependent on those that are harder to store and transport. Much depends on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine coming through in the quantities currently hoped. The EU is off to a slower start because it has less access to the Moderna and Pfizer versions, but the AstraZeneca shots should allow it to catch up later in the year. Deutsche Bank expects the U.K. to vaccinate faster than the others because it already has plentiful supply of AstraZeneca's vaccine. The following charts show how Deutsche Bank expects protection will be built in each of the U.S., the EU and the US. The critical point from the economic point of view is that Britain should vaccinate all its over-65s and health workers by March, while the US and the EU will have to wait until May and June:    Lots could go wrong with these plans, as the Biden administration will be acutely aware. If any vaccine supplier hits problems with their production targets, Uncle Sam will have to try to help. Approval for further vaccines would be a boost. A major problem with any vaccine could be disastrous, and shake confidence in all the others. Any significant hitch in the U.S. could also lead to embarrassing and politically damaging comparisons with Europe:  Both the U.S. and the EU also have to contend with geographical differences. Densely populated areas can expect to have greater problems thwarting the pandemic's spread. But they may also have the "advantage" that more people have already suffered Covid, so they are closer to achieving herd immunity. As these charts from Capital Economics Ltd. show, the Benelux countries, the most densely populated in the EU, have also had the worst experience to date with Covid-19:  With luck, "vaccine hesitancy" — public resistance to being inoculated — shouldn't be an issue for many months, and a successful rollout would go a long way to allaying concerns. But stronger and clearer messaging about the benefits and practicalities would help. So far, governments have been oddly hesitant to point out how big a difference vaccines could make. Both David Leonhardt of the New York Times and Bloomberg Opinion's Faye Flam independently make the point that more optimistic messaging would help. This is going to be difficult. All the models I've cited are as vulnerable to be disproved over the next few months as were models of the pandemic's spread last March. Now, as then, this subject will dominate our lives for months ahead, but neither the politicians who will command the effort nor the investors and financiers responsible for allocating capital know much if anything about it. We are all about to learn a lot. Let's hope (not just for Biden's sake) that we don't have to learn it the hard way. Presidential Stock MarketsHow might the 45th president have explained Wednesday's action on the U.S. stock market, had he still had access to Twitter? I'd suggest something like the following: The US stock market is at an ALL-TIME HIGH already after only one day of President Biden, higher than it EVER was under failing Trump administration.

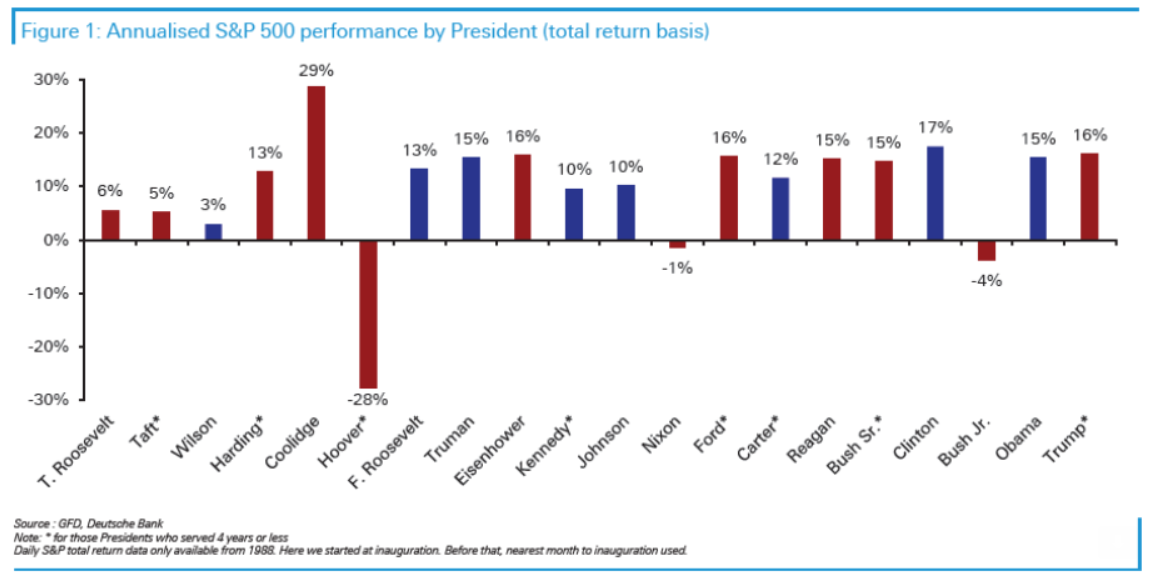

As I emphasized yesterday, this would have been silly. Presidents have little to no control over the market's drivers. Ultimately, they can't do much to get in the way of the forces of economic growth and compound interest. The following chart, from Deutsche Bank's resident financial historian Jim Reid, shows the average annual return (including dividends) of all presidents going back to Theodore Roosevelt. Only three presided over average declines. Since the Great Depression, all bar Nixon and George W. Bush averaged double-figure returns:  The main message should be that presidents don't make much difference. Several would look less lucrative if the data were given in real rather than nominal terms. But the U.S. has twice had streaks of five presidents who presided over double-figure average returns, and the current streak is only two. If the Federal Reserve keeps priming the pump and the vaccination effort goes successfully, then maybe, just maybe, the streak can continue. Survival TipsWhat meaning does life have? Or is it better just to assume that there isn't any great higher purpose, and we should get on with enjoying the journey? A kind reader pointed me to this fantastic graduation address at the University of Western Australia by Tim Minchin. (The language very occasionally veers in a direction you might not want to share with school-age kids.) It's profound and yet very funny, and it's shorter than Joe Biden's inaugural address. Worth listening. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment