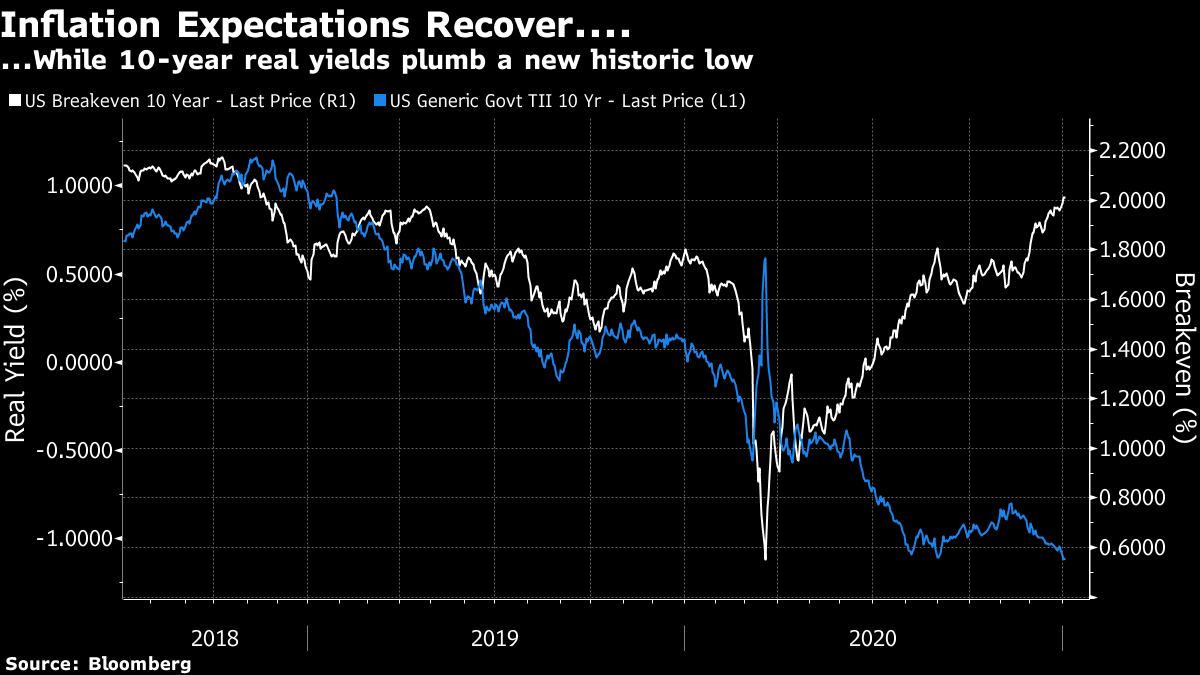

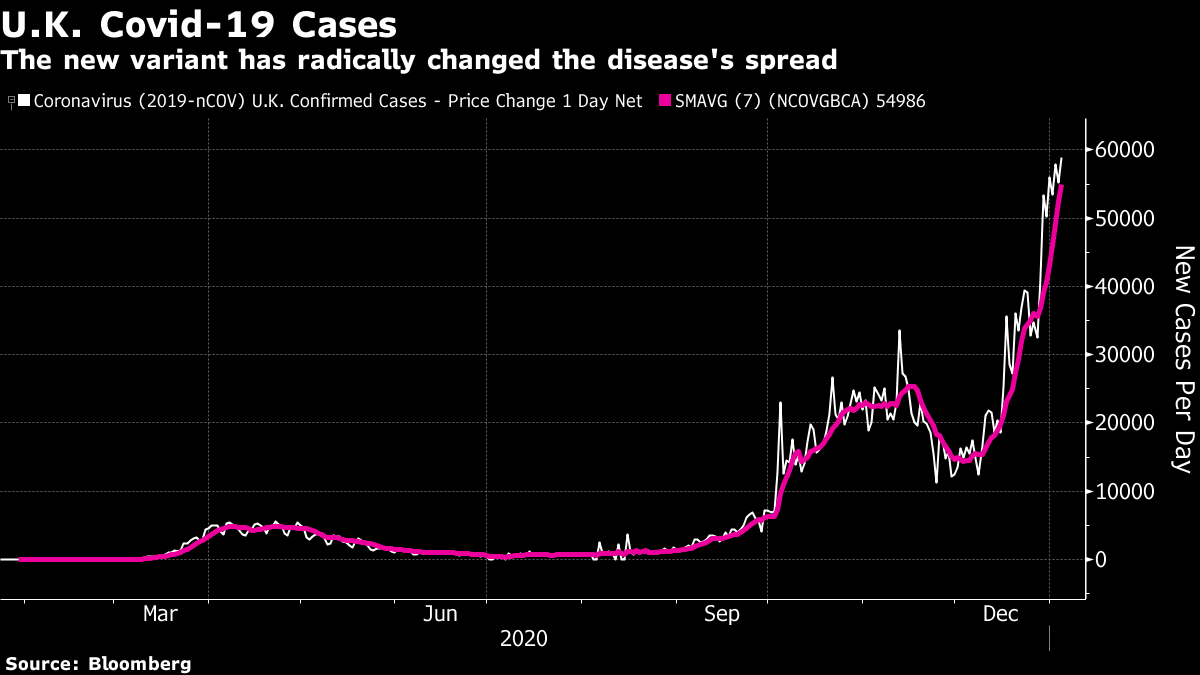

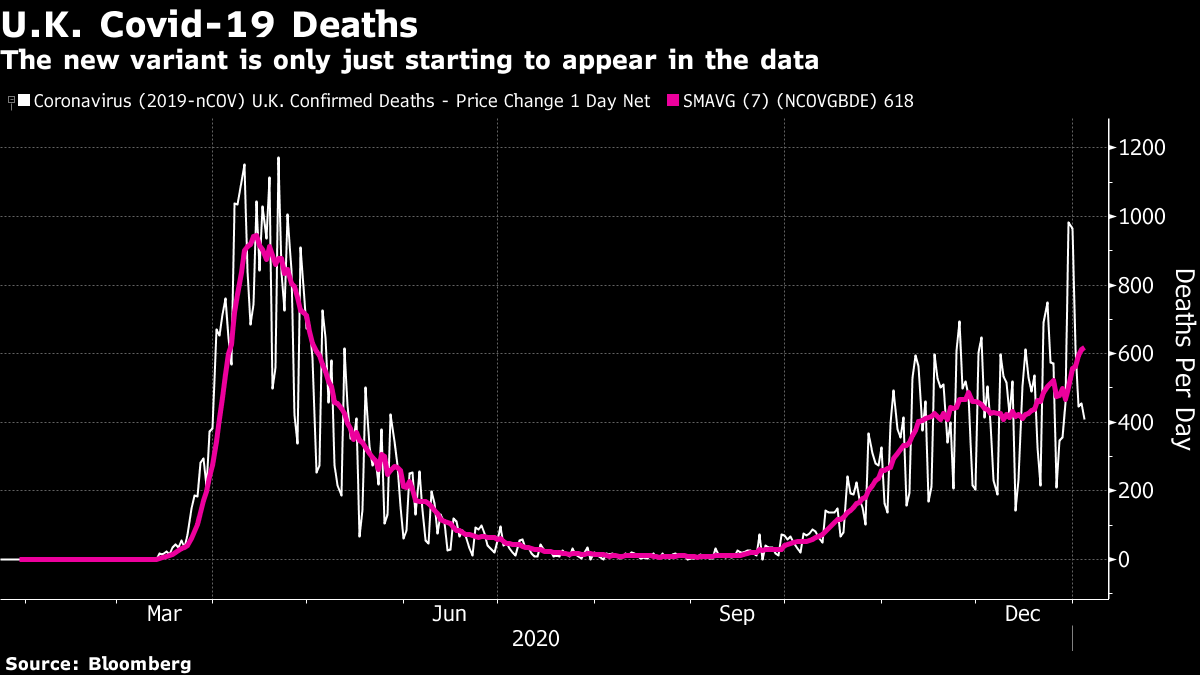

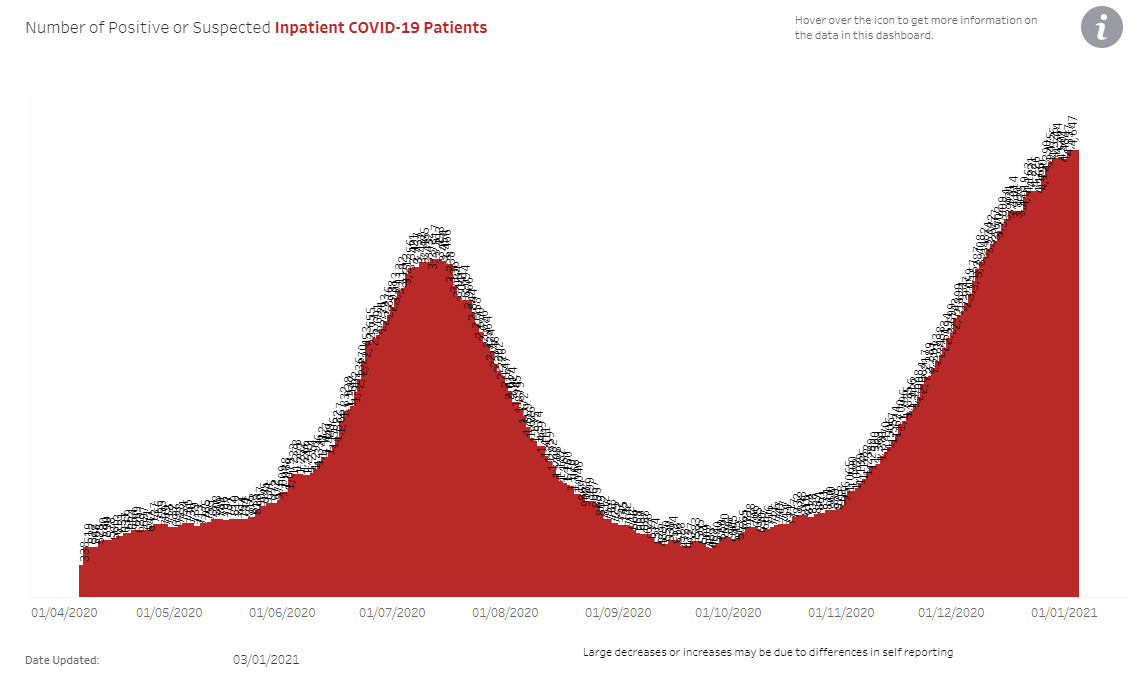

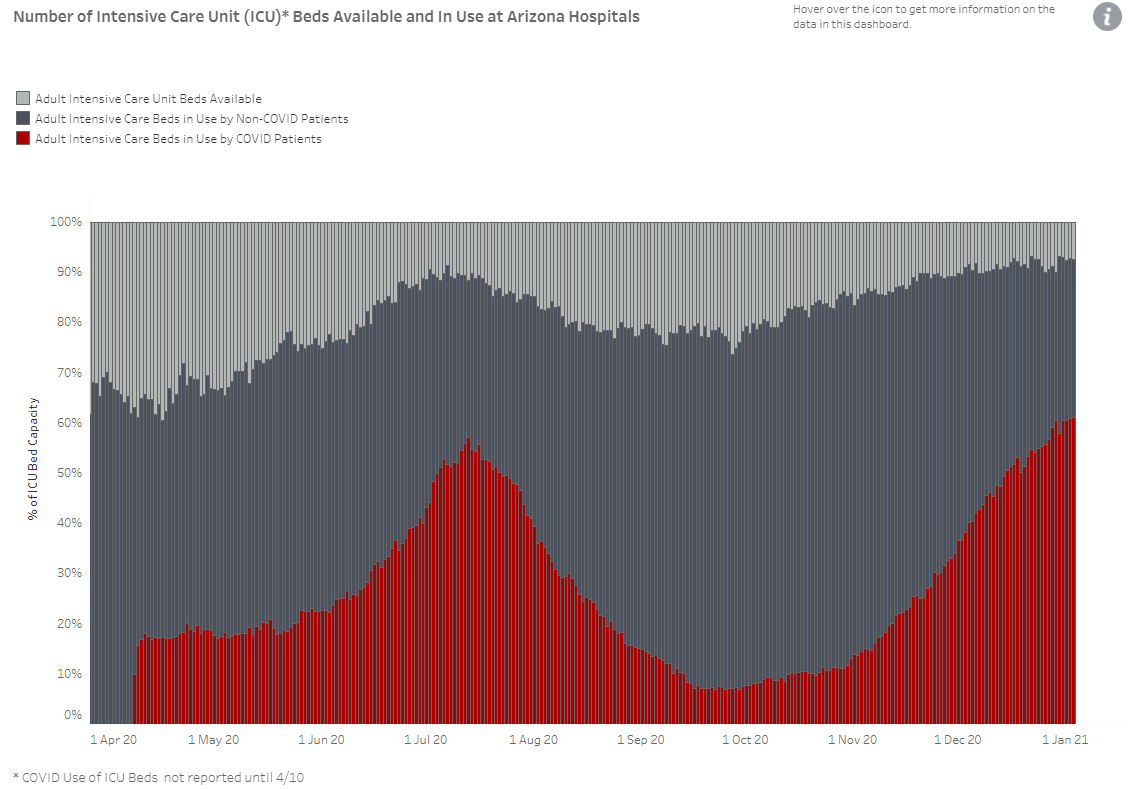

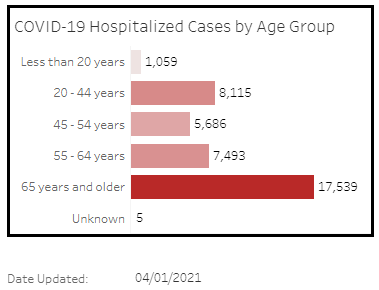

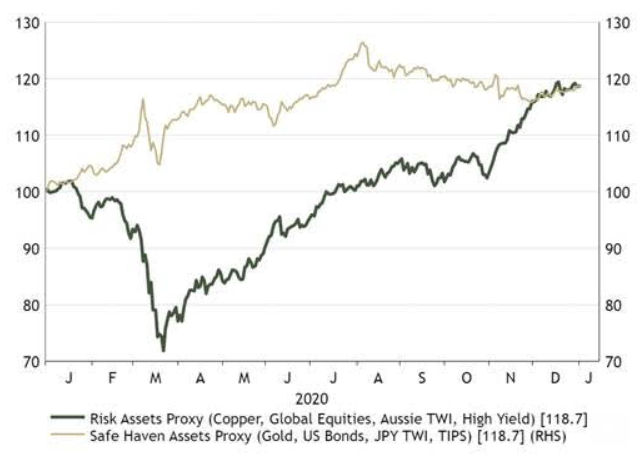

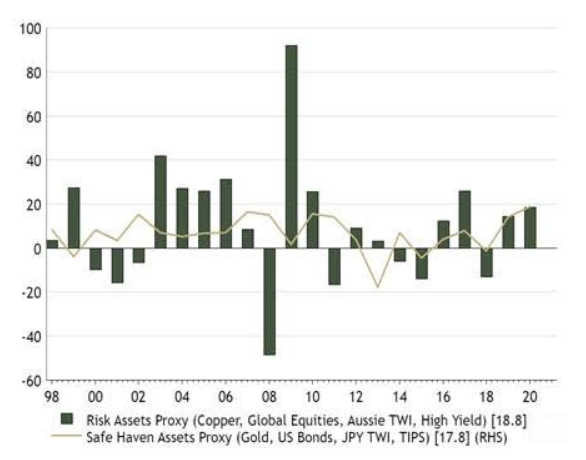

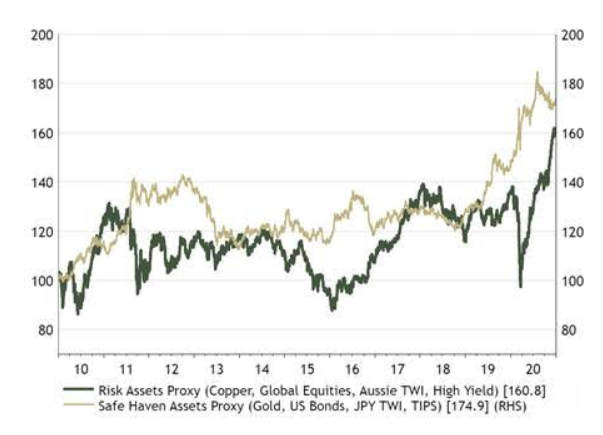

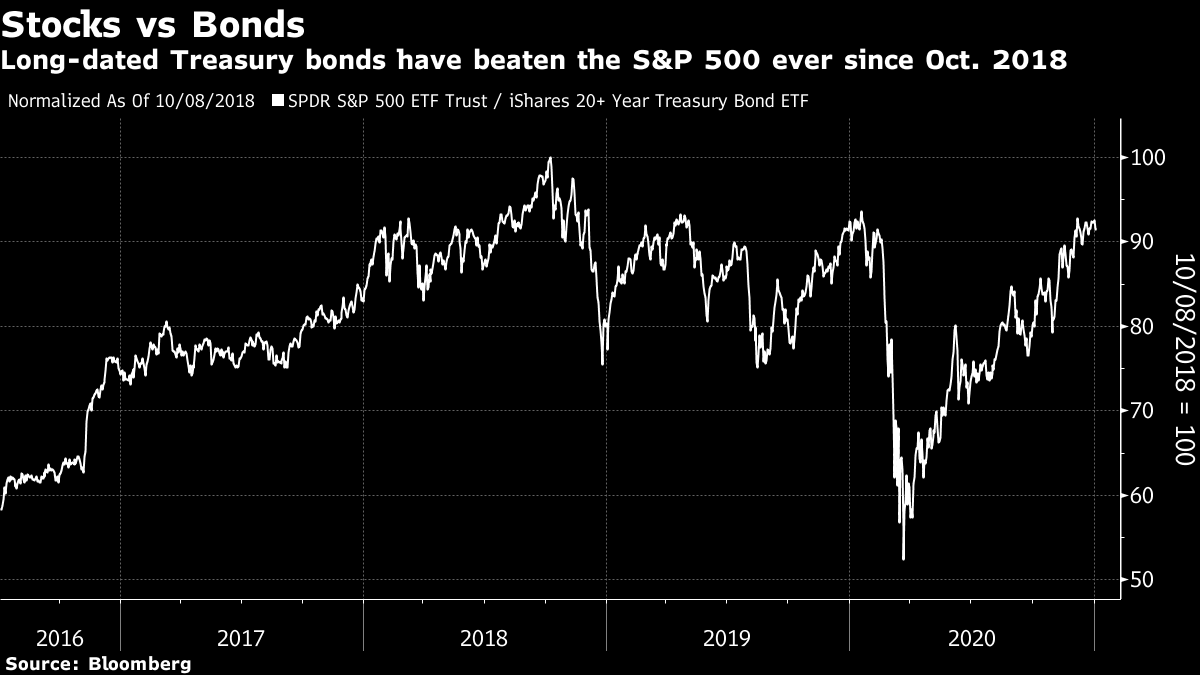

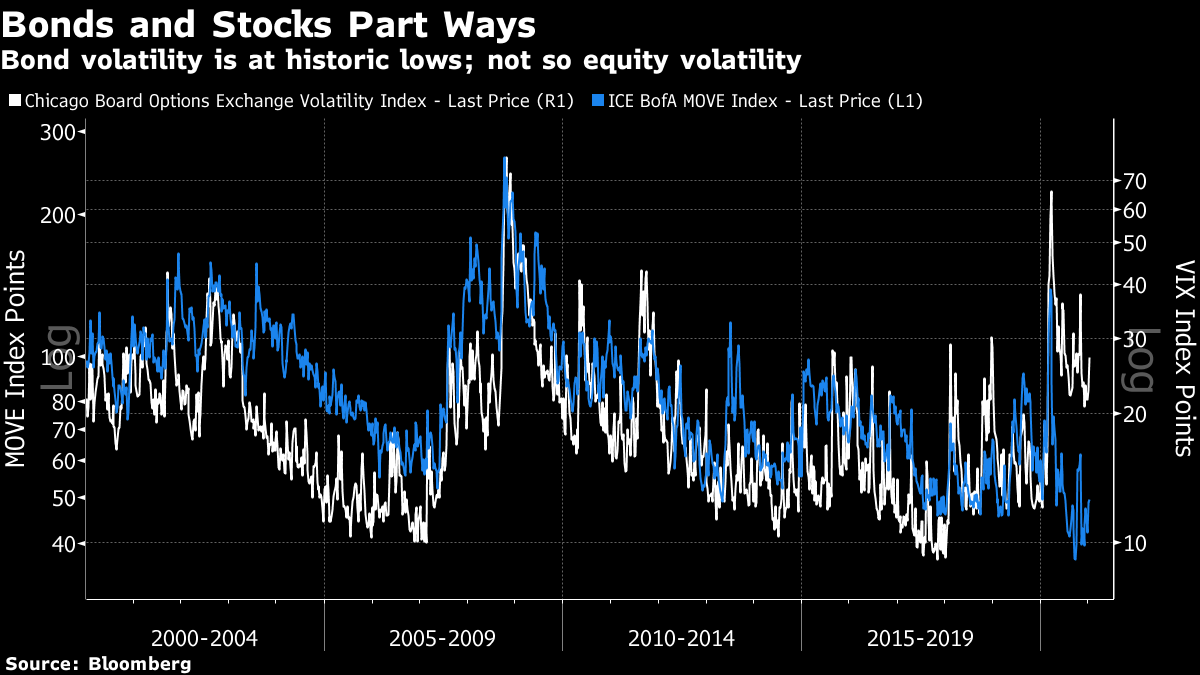

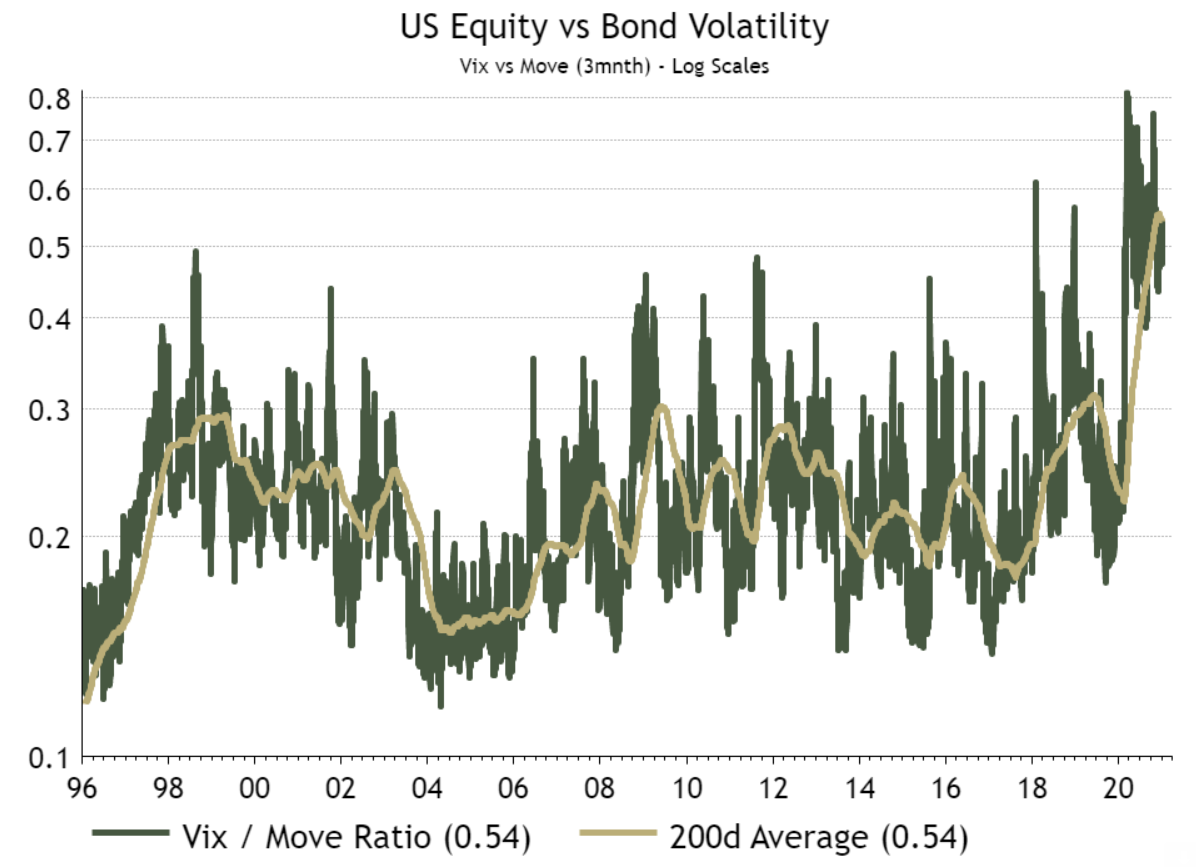

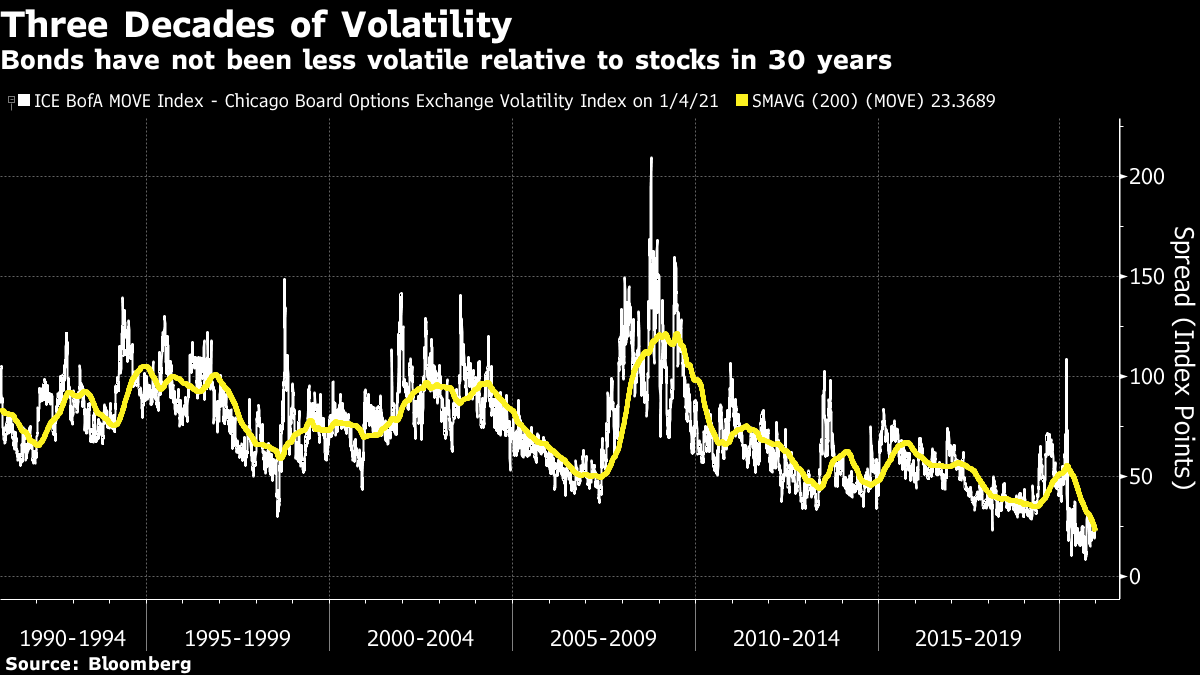

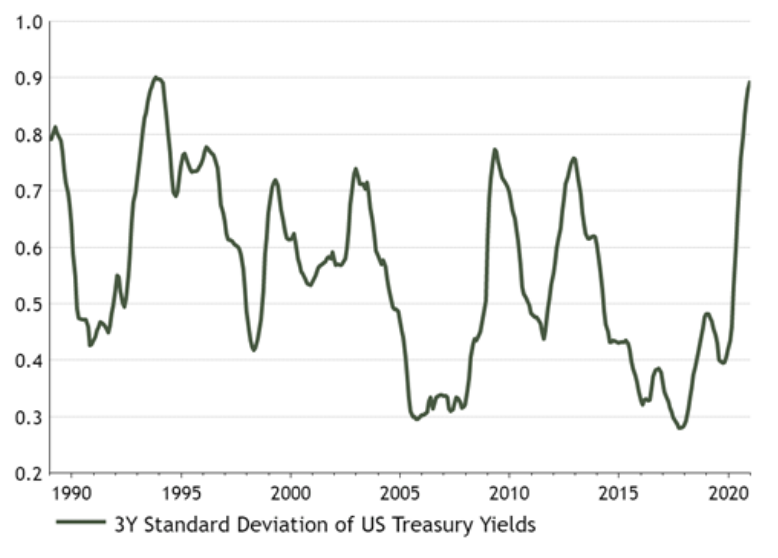

| To get John Authers' newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here. A New Year's ThudAll was not quiet on new year's first trading day. It began with a counterblast of negativity, as U.S. stocks had their worst decline since before "Vaccine Day" in early November, when Pfizer Inc. announced the great results of its Covid-19 inoculation trials. Cryptocurrencies took their first reverse in a while after a stunning rally. And all of this happened even as the over-arching macro case many had hoped for continued to play out, with 10-year U.S. inflation expectations breaking above 2% for the first time since 2018, while 10-year yields barely budged, bringing real yields to an all-time low:  This looks like something close to market Nirvana; the economy reflates on cue while rates remain utterly accommodative. So what gives? Naturally, U.S. political jitters matter a lot. The importance of Tuesday's Georgia run-off elections, whose results might well take a matter of days to ascertain, can be exaggerated. But the market outlook will be different if the Democrats can somehow win both seats, which is a real possibility. With few other binary risk events like this on the agenda, it makes sense that some might decide to take money off the table now. Survive this and the rest of the year looks good. The greater reason for concern is the coronavirus. Vaccine distribution is proving more of an issue than many in the markets had expected. We can soon expect to spend as much time checking vaccine-trackers as we used to spend on case and death rates. This means that Vaccine Day joy may have been premature; even with an effective treatment, getting doses to enough people to deliver herd immunity across the world will be almost as great a logistical task as the medical challenge of discovering it. But most important, there are nerves over the new variant of the virus. It doesn't appear yet to be any more deadly, but it certainly seems far more infectious. A picture is often worth a thousand words; this chart shows daily new cases in the U.K., where the variant was first identified in mid-December:  Such numbers are shocking. Britain on Monday became the first nation to administer a second dose of the Pfizer vaccine to a patient, but it looks as though it arrived agonizingly too late. Thus the U.K. government reversed its previous course (after markets had closed trading for the day), and announced the re-imposition of a strict lockdown across the country to last into next month. Schools will close and — very tellingly — the national exams that decide university and college entrance, usually taken in June, have been canceled. The vaccine hasn't arrived in time, then, to stop a dreadful impact on national morale, and probably a major hit to economic activity. The good news is that deaths remain lower than their level in March, when there were far fewer cases. But with the explosion of infections, and the fresh pressure on the health service, it will be very difficult to keep it that way:  The variant has already appeared in a number of other places, including the U.S. — a much bigger country where the roll-out of the vaccine will create much greater logistical problems. To illustrate how serious the U.S. situation is, I would like to return to Arizona. Long-standing subscribers will remember I wrote a lot about Arizona as it fell victim to the second wave of the virus last summer. The state has an informative but sometimes confusingly presented Covid dashboard, and many misread it. After several weeks of acrimonious correspondence, we all got to the bottom of what the Arizona Covid-19 data were telling us, and then the summer wave steadily subsided. Here are the key indicators of what is happening now. The number of positive or suspected inpatient Covid-19 sufferers is the highest on record (this is the best measure as formal Covid diagnoses often took a matter of days during the early months of the pandemic):  Meanwhile, Covid patients (in red) account for a record 61% of Arizona's intensive care beds, while only 7% of ICU beds state-wide are vacant, the lowest since the pandemic started:  If we look at the breakdown of those hospitalized by age group, we make the horrifying discovery that most are under the age of 65:  Plainly, the likelihood of being seriously sickened by Covid-19 increases sharply with age. But when 56% of those hospitalized with Covid-19 are below retirement age, it is clear that this disease does more than prey on the elderly. Note also that Arizona has warm winters and might be expected to have less of a seasonal effect than most states, and that this baseline has been set before the new variant arrives. The base case for markets should still be that the end of the pandemic is in sight, and that life will be back to more or less normal by the end of summer. But the numbers from Arizona and the U.K. demonstrate why investors are getting jittery. Risk-On or Risk-Off?Fortune favors the bold. And blessed are the meek for they shall inherit the Earth. Both those things came true simultaneously in 2020. The following chart, from Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research in London, shows the performance of two broad proxies for "risk-on" and "risk-off." The risk-on basket smooshes together copper, global equities, the Australian dollar and high-yield bonds, while the haven, or risk-off, basket has gold, Treasury bonds, the Japanese yen and Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS. Amazingly, these very disparate investments performed almost identically to each other. Both baskets enjoyed a fantastic year, gaining almost 20%.  Harnett sent this to me as I was trying to digest the weirdness of a day with elevating stock market volatility as the bond market stayed preternaturally calm. In the first few years of the global financial crisis and its aftermath, we all grew used to the phrases "risk-on" and "risk-off" as whole asset classes would move according to top-down views of whether risks arising from the crisis were rising or falling. Now those rigid definitions are breaking down. I prodded Harnett for more. The next chart confirms that for a few years after the crisis, the two tended to move in starkly opposite directions. However, 2020 doesn't look like the historic year one might expect, given the shock that occurred. Risk-on and risk-off assets performed to a more coordinated extent than ever before, but in both cases they did only slightly better than in 2019:  Meanwhile, if we look at cumulative returns for the post-crisis decade, we discover that the "risk-off" basket has outperformed almost throughout. This against the backdrop of a decade that saw an almost uninterrupted bull market in stocks:  This might help to confirm the intuition that stocks need bonds, or low-risk assets in general, in a way that did not use to be the case. Caution has prevailed for a decade, but created the conditions in which investors felt that they had little choice but to buy stocks and other risk assets. Thus both did excellently. To ram that point home, note that stocks peaked relative to bonds (as proxied by two popular exchange-traded funds) in October 2018, and have never revisited that high. (I hope and believe it is a coincidence that stocks topped out on my first day of work for Bloomberg.) Since then, equities have gone on to hit records — but they still haven't done as well as bonds.  Something strange has been happening to the relationship between risk-on and risk-off in the last few months, and that can be shown in the link between bond and stock volatility (as popularly measured by the ICE BofA MOVE Index and the CBOE VIX index). Generally, as the following chart shows, they tend to move together, which makes perfect sense. Any given shock is likely to have a big effect on both stocks and bonds, even if it pushes them in different directions. But in the last few months bond volatility has dropped to its lows for the century, while stock market volatility remains elevated. Why?  It is too easy to blame the Federal Reserve and other central banks. They've been pumping money into bonds as a means of propping up stocks for most of the last decade, and this phenomenon has only emerged in the months since the pandemic hit. To illustrate how sharp the divergence is from previous history, here is the VIX/MOVE ratio, as graphed by Harnett of Absolute Strategy:  And here is the spread of bond volatility over equity volatility, as cooked up by me on the terminal:  Bonds' remarkable placidity explains the relationship in the chart with which I started this newsletter. With nominal yields staying stubbornly below 1% even as inflation expectations return to normal, the result is historically low real yields. This is good news for gold (up on Monday) and awful news for rate-sensitive sectors such as financial and real estate (down a lot to start the year). Such low bond yields allow stocks to keep rising, and also let them exhibit unusually high volatility, to reflect the risks that still abound, without undermining the overall positive environment. All of this is happening even as the Fed publicly eschews deliberate "yield curve control," or targeting a specific level for the 10-year yield as the Bank of Japan has done. While bond market volatility stays this controlled, risk-on assets can continue to party. But they also have to absorb any differing risk climate because the bond market is no longer doing so. Strange days indeed, as someone once said. Also strange: As Harnett shows in this chart, overall bond market volatility over the last three years has actually been very elevated, as the 10-year yield pierced 3% and then barely 18 months later dropped below 0.5%:  Bonds' lack of volatility is a sudden and recent development. A lot depends on whether it can continue. A Democratic sweep in Georgia would put it to the test. Survival TipsNew Yorkers, this one's for you. There cannot possibly be a more fun way to give to coronavirus relief charities than through the Spireworks app. I have no idea how they do this, but this is an app you can download on to your mobile phone, that will then allow you to control the lights on top of a number of New York landmark skyscrapers. Each time you take over the controls, you need to pay some money to charity. Judging by the impact on my 11- and 13-year-old children on a trip to midtown Manhattan last week, this is a winner. Both are showing worrying symptoms of being "too cool for school." But with the Spireworks app, a $10 donation to coronavirus relief gave us three minutes to control the lights on the spire of One Bryant Park, the enormous futuristic glass skyscraper that Bank of America Corp. uses as its New York headquarters. During their three minutes of controlling this building like a couple of Batman villains, my kids changed the spire into multiple colors, found out how to do a strobe effect and produce pulses and sparkles. It's quite intoxicating fun, recommended for all New Yorkers; and if there are any budding social entrepreneurs who'd like to try doing something similar in other cities, go for it. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment