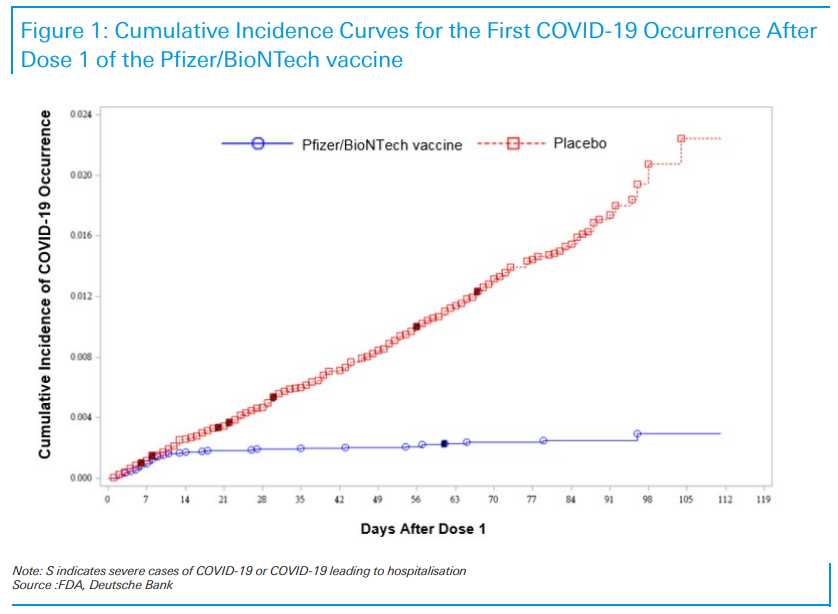

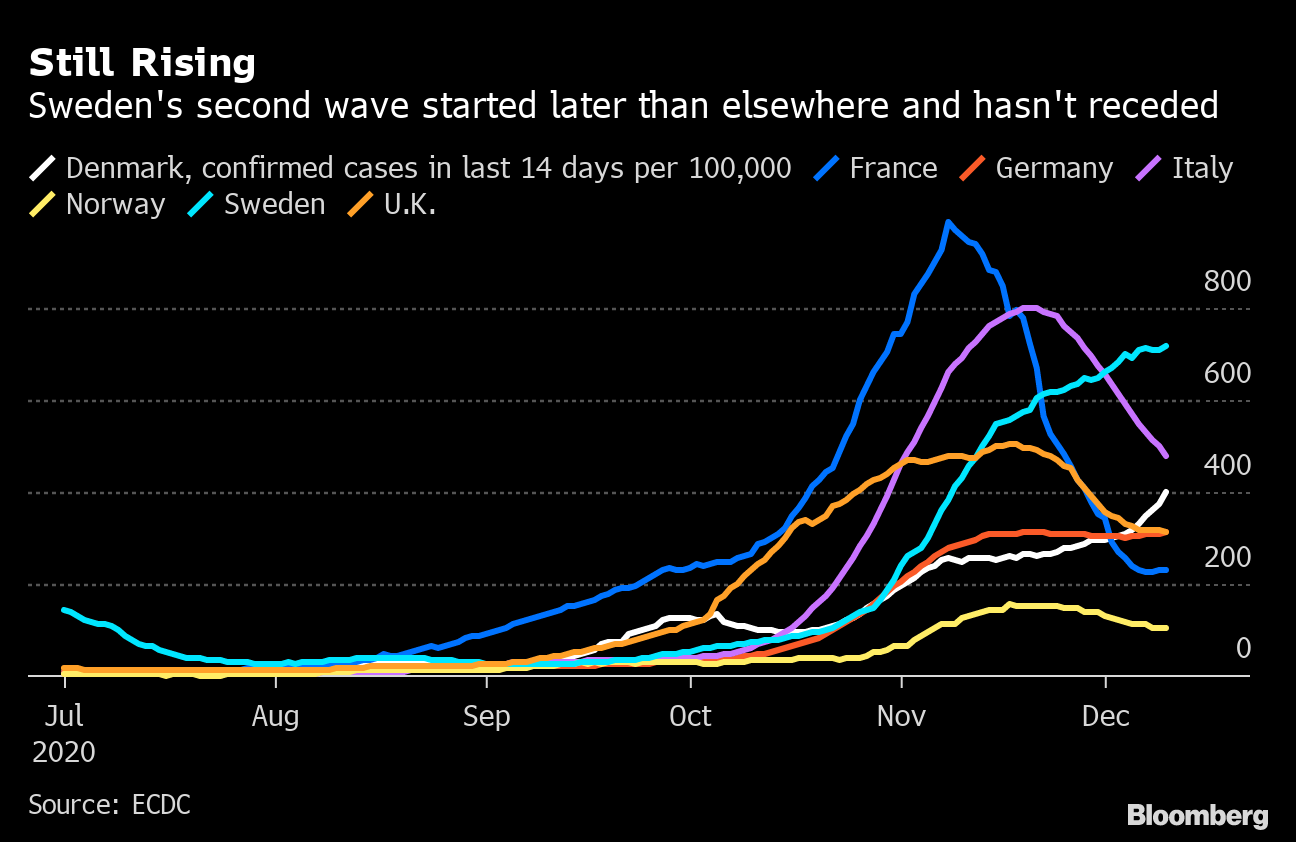

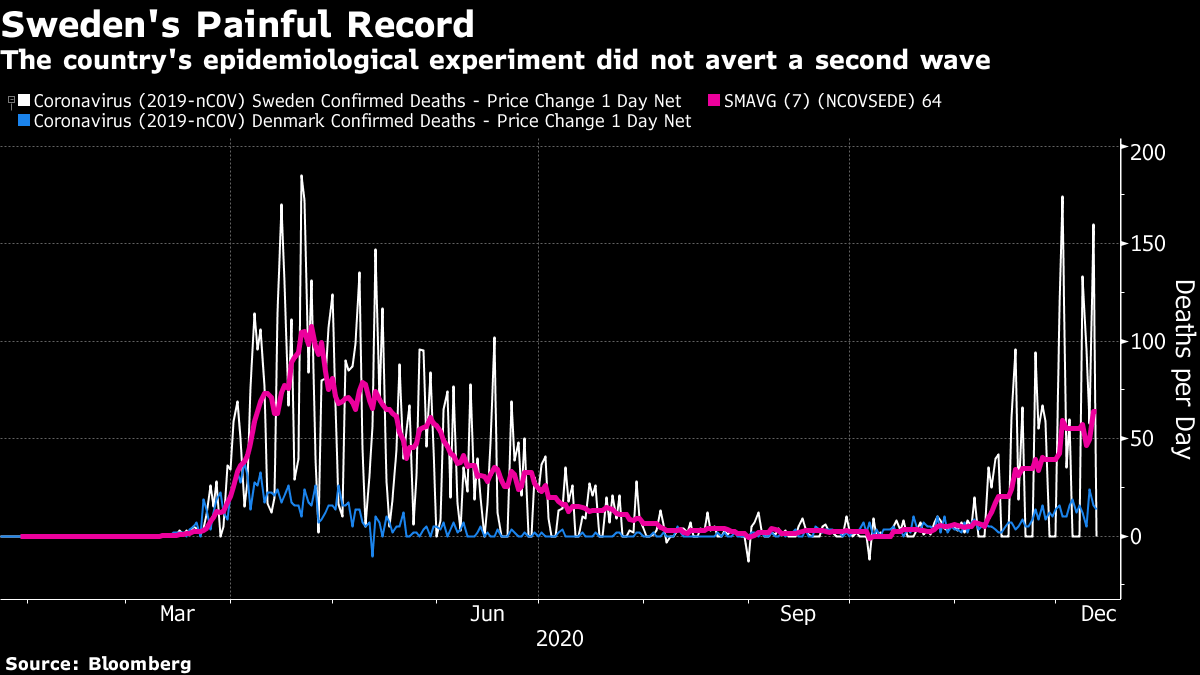

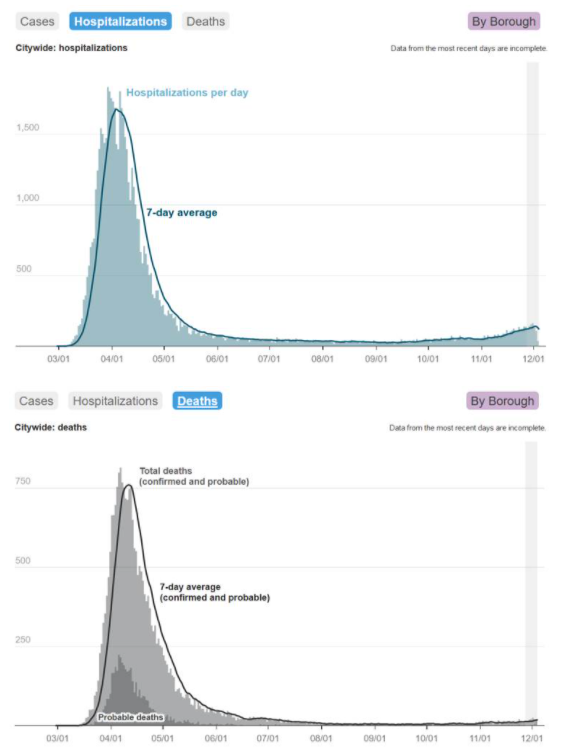

The Moment We've Been Waiting ForIt's time for some good news. A few hours before I wrote this, my father (who is 83 and had a nasty case of pneumonia a few years ago) phoned to tell me that he will be having his first Covid-19 vaccination shot this week, with a second to follow in the first week of January. My 81-year-old mother will get her jabs at the same time. The British rollout continues apace, just as the introduction of the same vaccine is ready to start in the U.S. It's an exciting development. After a miserable year, my parents can plan on returning to an active and happy retirement. As this fascinating chart by Deutsche Bank AG with FDA data makes clear, the Pfizer Inc. vaccine, which will be going into my parents' arms, has no significant effect for the first week. After the second dose, the effect compared to the placebo is dramatic and undeniable. The menacing curves of new Covid cases should no longer look like the red line, but the blue one:  The distributional challenges remain intense, given that this vaccine needs to be kept very cold. Beyond the logistical challenge, there are moral ones. In Britain, elderly patients who are at most risk, like my parents, will go first. In the U.S., with different states free to make different decisions, there is a risk of dissension. There are powerful though controversial cases to be made for giving priority to prisoners, who are at great risk; there is also a case for giving lowest priority to those who can easily work from home. And there are also arguments about international equity; as Covid knows no political boundaries, it might be "enlightened self-interest" for wealthier nations to distribute vaccine supplies to poorer countries on their borders, or to parts of the world that have particularly severe outbreaks. Such decisions would be controversial. The past couple of months have made clear that the world needs a vaccine to put the pandemic behind us. The resurgence of the virus has done great damage to the rival theory, that "herd immunity" (where the disease runs out of new people to infect) could be reached soon by allowing it to spread in the population. Sweden famously eschewed strict lockdowns and left its schools open. The hope was that this would bring herd immunity, so that it would avoid a second wave. That theory now looks very questionable. In the following chart of confirmed cases per 100,000 over the last 14 days, Sweden is in pale blue. It is suffering a second wave fully comparable with those of other European countries. Unlike those that locked down, its cases are still rising:  Sweden's hospitals are at capacity, and it is drafting in help from other countries. The popular argument that it had done something uniquely clever still had much to recommend it two months ago. It is very hard to sustain now. Put differently, this chart shows deaths per day in Sweden and neighboring Denmark. I multiplied Denmark's number to account for its smaller population, and provided a seven-day moving average for Sweden, whose data are very noisy. Sweden endured an appalling death rate compared to Denmark's; and it is once more suffering a worse death rate than its neighbor. There is room for argument about definitions, and Sweden's numbers may be inflated by a particularly mild flu season last year; but the notion that it has gained from its relaxed attitude to social distancing now seems close to impossible to sustain:  This isn't to say that debate on the merits of lockdowns has been wasted. Plainly, they have serious economic consequences, and school closures may have lasting negative consequences for children. But there was no "free lunch" to be had by letting the disease rip. The many trade-offs were, we can now see, far subtler. It's also fair to say that the herd immunity theory had something going for it. Places that suffered the worst outbreaks in spring have enjoyed noticeably easier times in the last two months. The following charts are for New York City, blindsided by the pandemic earlier this year. Both in terms of hospitalizations and deaths, the current wave isn't remotely comparable to the first:  Part of this will be due to the salutary effect of the spring outbreak, which left New Yorkers in little doubt that it was worthwhile to wear masks, and socially distance. However, they are also consistent with the notion that the first outbreak increased immunity in the population and made it harder for the virus to take hold a second time. Whitney Tilson of Empire Financial Research, whose work on coronavirus I have recommended in the past, offered the following mea culpa in his most recent bulletin, having previously used the herd immunity theory to predict that the current waves in the U.S. and Europe would be far less severe than the previous ones: in failing to anticipate the magnitude of the latest third wave in the U.S. (and second wave in Europe), I made two mistakes: Most importantly, I didn't fully appreciate that while some hard-hit areas (northern Italy, the greater NYC area, and parts of Florida) likely reached the herd immunity threshold, the vast majority of the U.S. and Europe did not – and hence were vulnerable to another terrible wave… My second mistake was failing to anticipate how quickly after the earlier wave(s) most Americans and Europeans (both citizens and their governments) would become careless/complacent and, especially in the U.S., the politicization of this public health issue and the resulting resistance to even easy, basic things like wearing masks. As a result, the virus came roaring back…

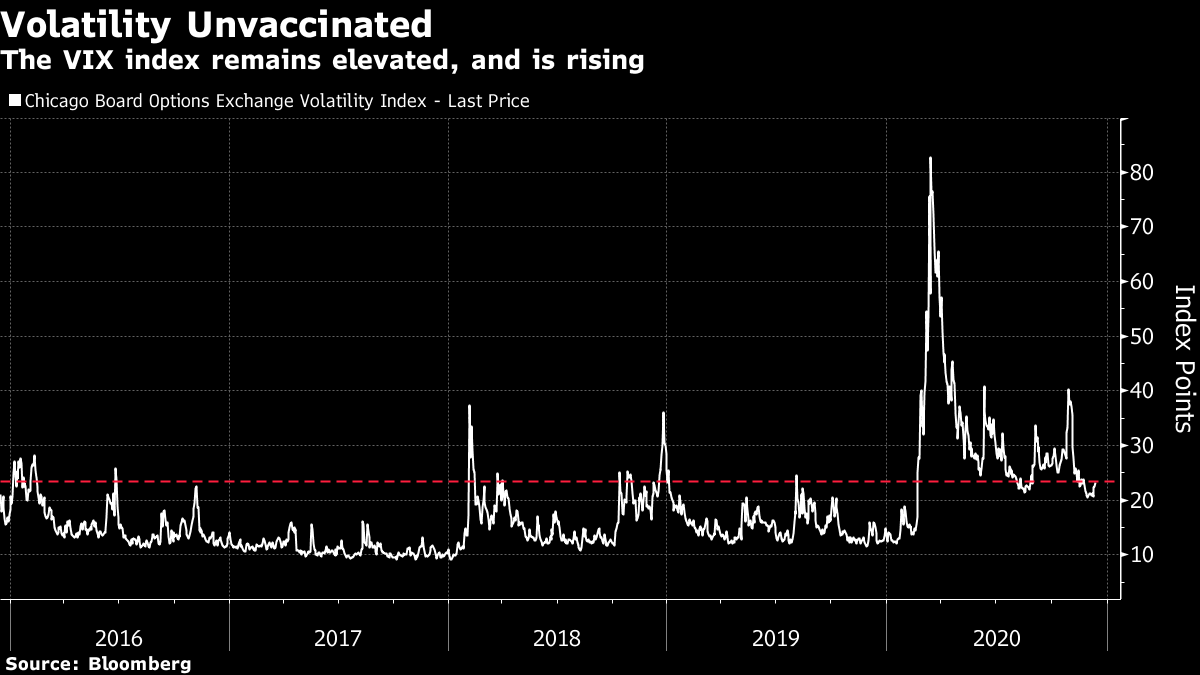

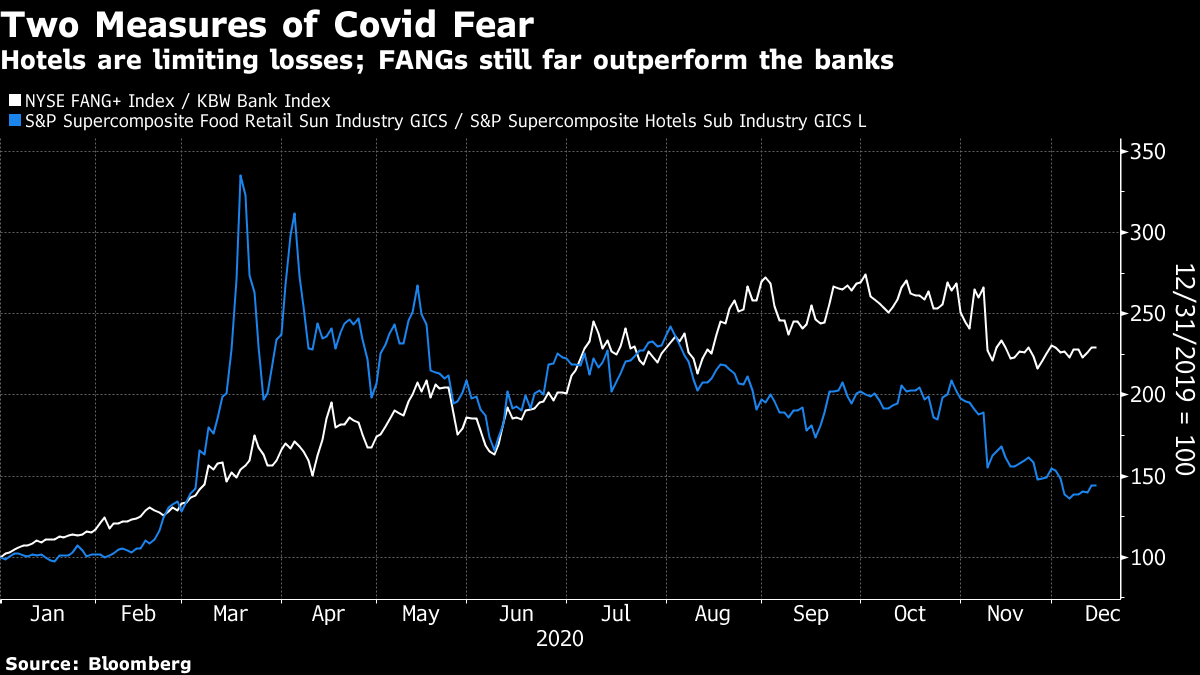

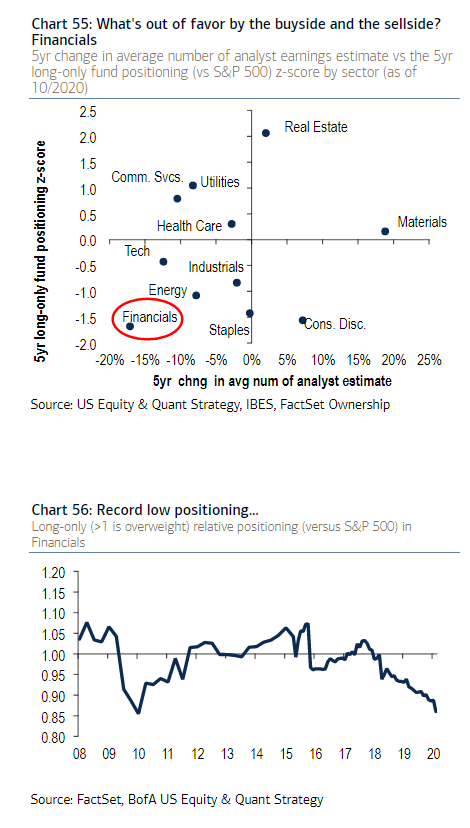

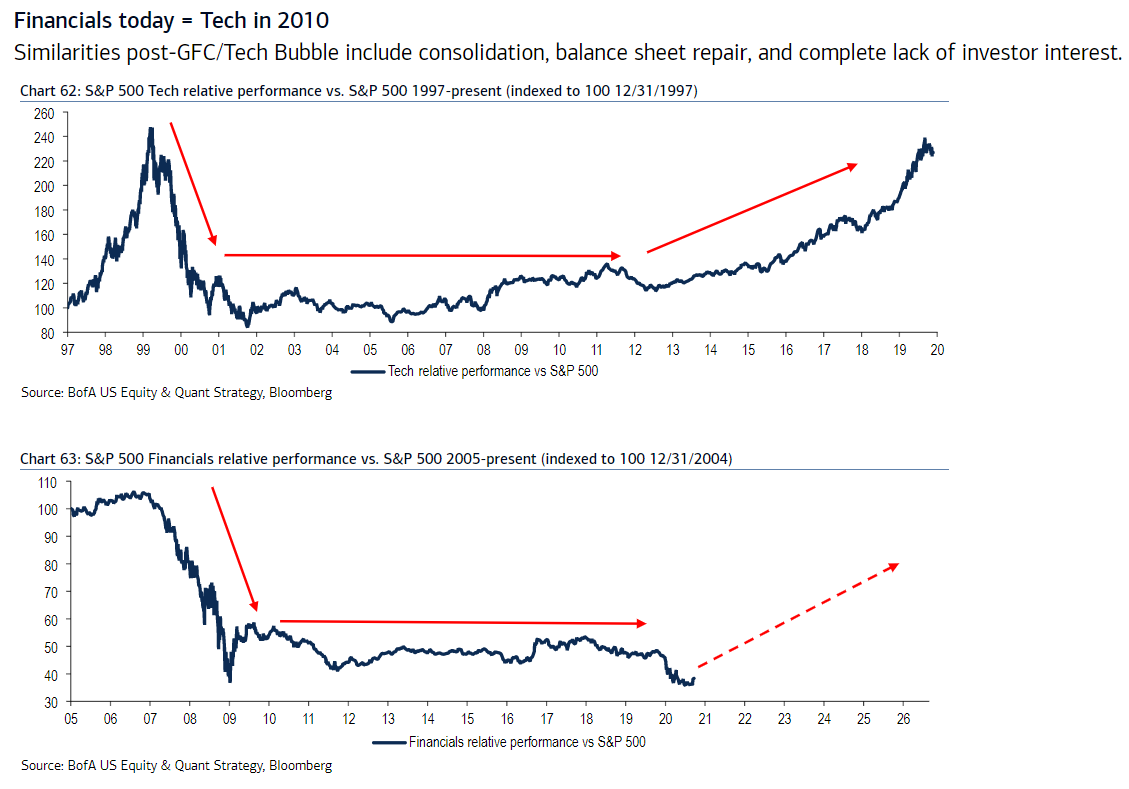

With the numbers affected now at dreadful levels once again, and months to go before enough of us are vaccinated to take life back to normal, it would make sense if everyone carried on in a careful and socially distanced way. It won't be fun, and it will be negative for the economy, but a few more months of slow activity should have little impact on market prices with the vaccine now available. That brings us to the next issue: Taking Vaccines to the BankIn markets, the vaccine has had less impact than might first have been thought. Obviously, the news had much to do with the fantastic performance of risk assets in November. Now, though, the VIX volatility index is rising again, and remains elevated by recent standards. It is only slightly below its peak the day after the Brexit referendum in 2016, for example:  It's possible that the ongoing attempts to overturn the presidential election result in the U.S. are unnerving investors, but it remains surprising that the vaccine hasn't had more impact, as markets are supposed to care more about the future, which now looks more settled than it did a few weeks ago. Within the stock market, the interplay between Covid winners and losers is also surprising. The following chart shows two measures of fear; the performance of food retailers relative to hotels and cruise lines (comparing the sectors most directly affected by social distancing and lockdowns), and of FANG internet platform groups compared to banks (comparing the sectors seen as the greatest beneficiaries and losers from a long-term environment of low interest rates, which is now widely expected to deal with Covid). These show a different pattern. The most immediate victims suffered worst early on, and are recovering. Food retailers have now beaten hotels by less than 50% for the year. But while the gap between the FANGs and the banks narrowed sharply on "Vaccine Monday" when Pfizer's results were first announced, they haven't moved since. The view that the future is far brighter for internet platform stocks than for banks hasn't shifted. This is true even though Facebook Inc. has now joined Google in the crosshairs of an antitrust suit:  There are various ways to try to take advantage of this. Much attention has been devoted to the extreme optimism surrounding the FANGs. But we learned again this year that shorting stocks in the grip of speculative excess can be dangerous to your wealth. It might be more appealing to look at the other side of the trade. The following charts, from Savita Subramanian of BofA Securities Inc., show the sectors that are in and out of favor with the buy-side (looking at long-only funds' positioning) and the sell-side (looking at the change in the number of brokers offering earnings estimates). Financials are spectacularly out of favor:  With the vaccine should come more economic activity, higher interest rates and steeper yield curves, all of which would be good for banks. Meanwhile, another chart from Subramanian makes a perhaps rather hopeful comparison with positioning in tech stocks:  After the tech bubble, the sector tanked and then flat-lined for a decade before starting a steady path back to dominance. So far, banks are following a similar path from their disaster of 2007-08. Now may be their time. At this point, it looks like financial stocks are discounting more future bad news than they should, and that there is plenty of room for them to appreciate. So one sensible way to profit from the market's reaction, or lack of it, to the vaccine news of the past month might be to take a deep breath, do some research, and buy some shares in undervalued banks. CAPE ConfessionIn the last Points of Return, on the debate over Robert Shiller's cyclically adjusted price-earnings multiple, I included some bond arithmetic to illustrate how much the price of the 10-year Treasury bond would need to fall to move the yield up 2 percentage points. This contained a grotesque error: I used a perpetual bond, which is a simple calculation but a security that barely exists these days. I needed to take account of the fact that there were only 10 years for the bond to keep paying out. As a result, I suggested that the bond price would need to fall by two-thirds; several of you pointed out that the correct number was closer to 18%. The point remains that it is possible for stocks to perform very badly for the next few years, by historical standards, and still outperform bonds. More feedback on this topic continues to be welcome. Survival TipWe've lost another of the greats. David Cornwell, who wrote under the nom de plume of John le Carre, has died at the age of 89. I prefer not to regard him as a spy novelist. Even though virtually all of his books deal with the dirty and treacherous business of espionage, his novels transcend the subject to make piercing points about the human condition and society. His range was remarkable, his prose superlative, his insight into character matchless. I happened to read his last novel, Agent Running in the Field, only last week. Set in a seedy part of North London (I think a key scene takes place in a cafeteria in Finsbury Park), it tells a tale of disillusion and confusion in a world dominated by Brexit and Trump. If not his greatest, it's still a great read. For those who haven't read any le Carre, try The Spy Who Came In From the Cold — probably the best spy thriller ever written. Other favorites are The Honourable Schoolboy, set in Asia, and The Little Drummer Girl, on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. His books convert well to the screen. The recent setting of The Night Manager is superb. And for a classic of television, try Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy on the hunt for a Soviet "mole" at the top of British intelligence, made by the BBC in 1979 and starring Sir Alec Guinness. Some find it hard to get into at first, but ultimately it is mesmerizing. Rest in peace, John le Carre. And have a good week, everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment