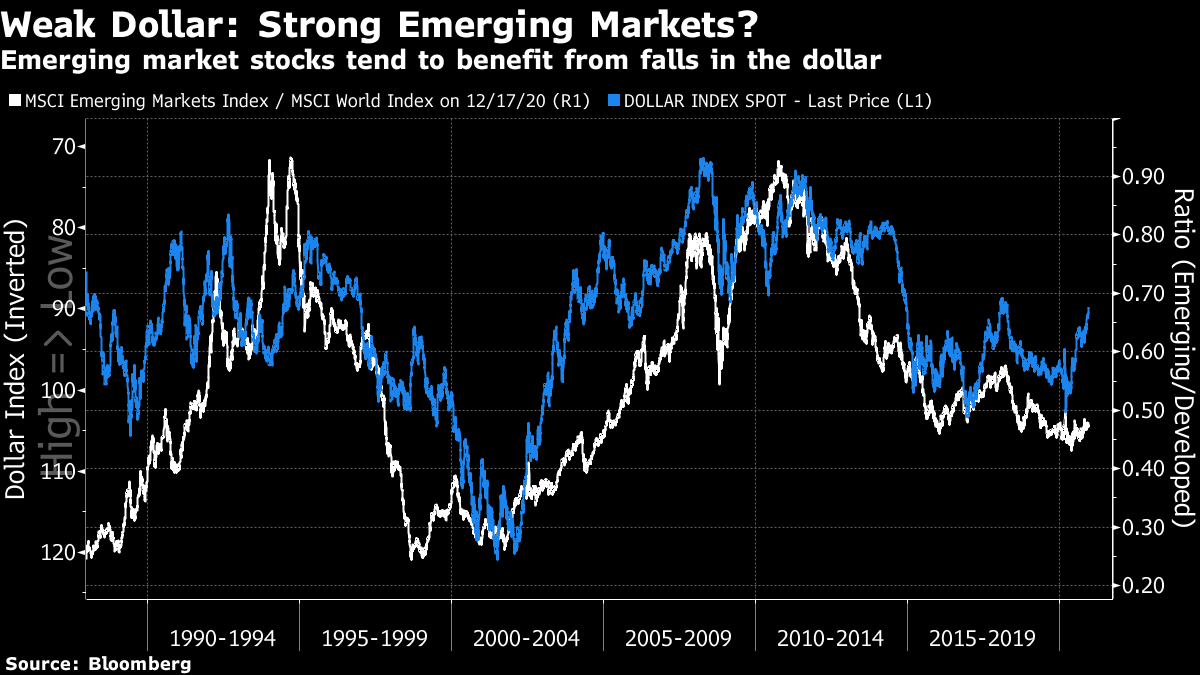

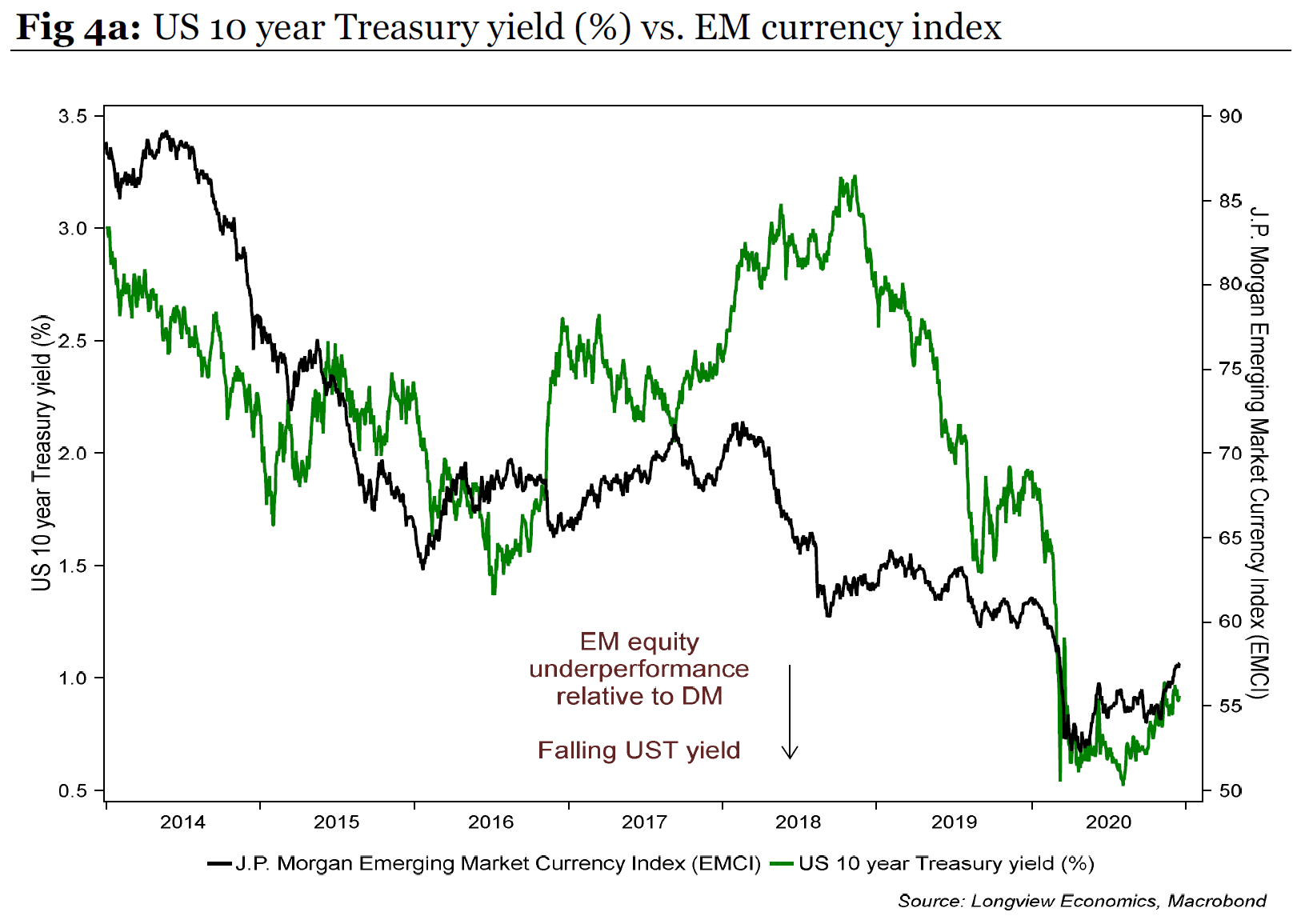

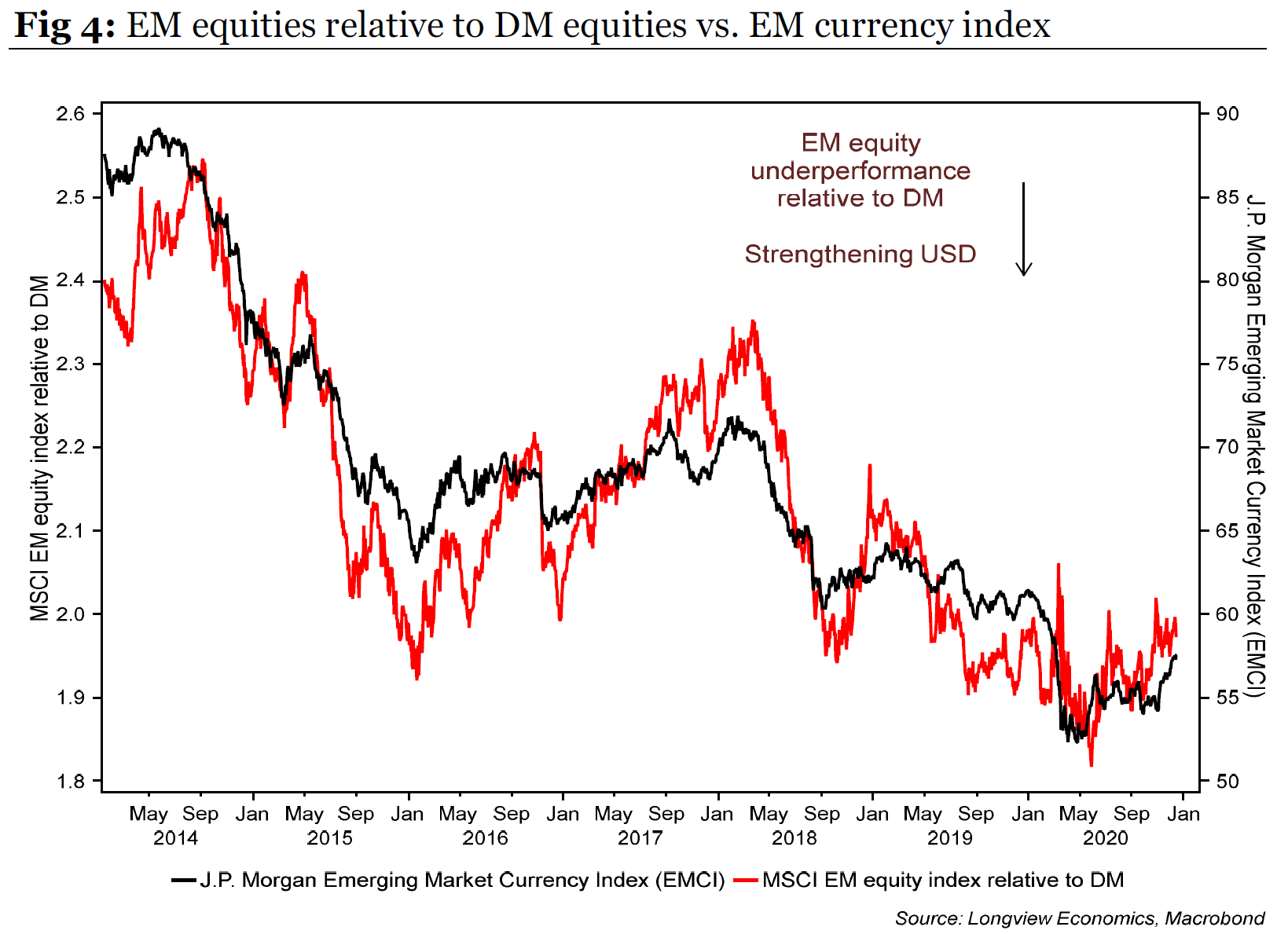

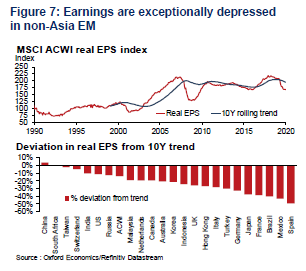

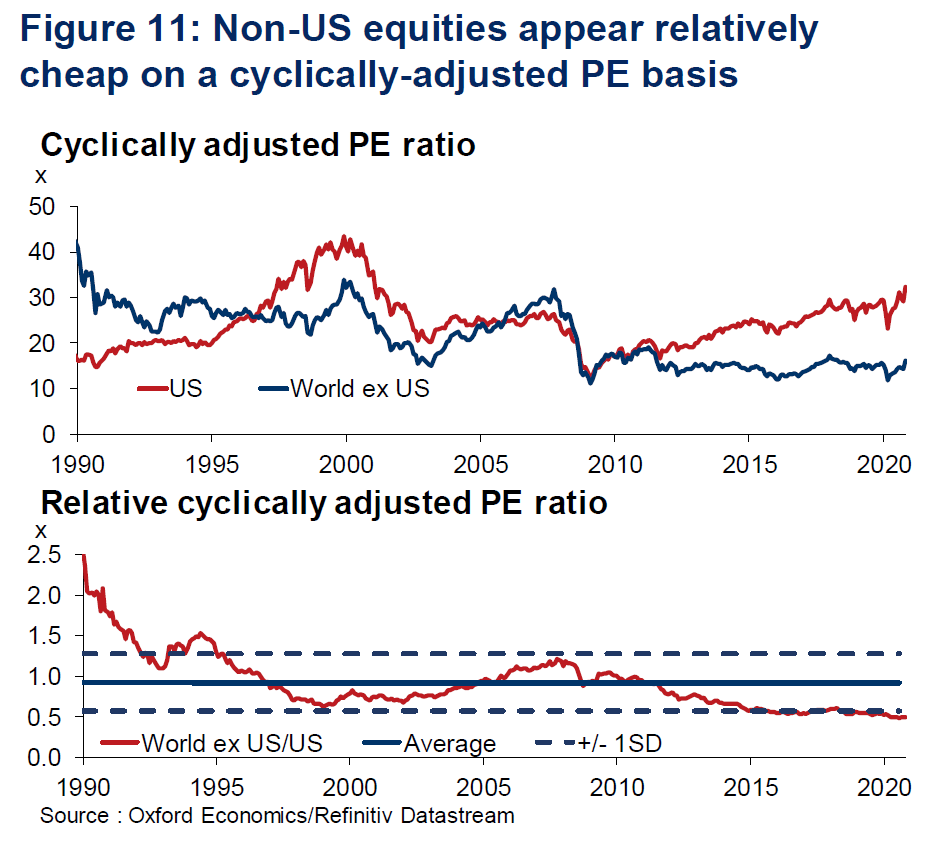

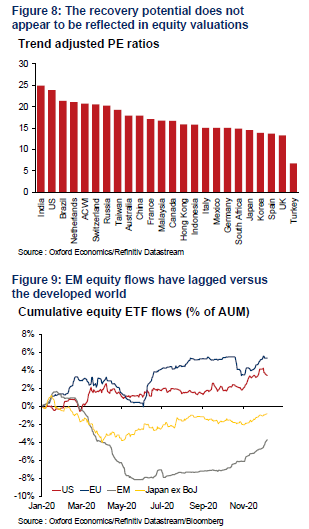

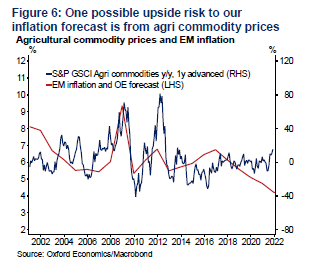

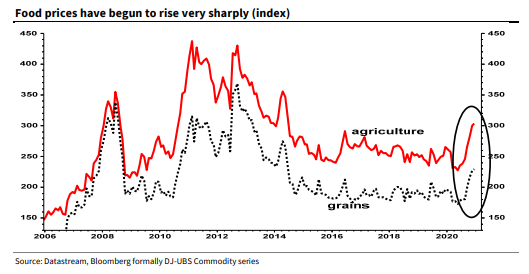

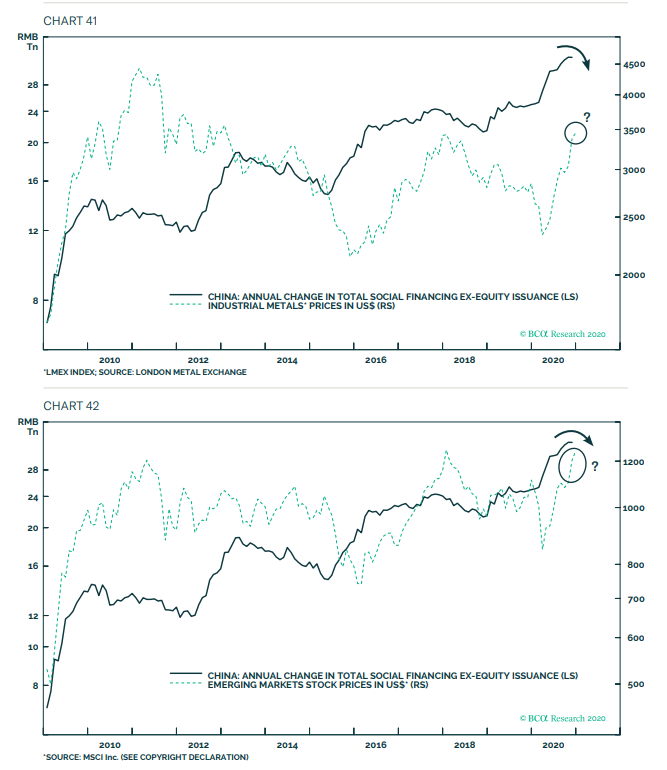

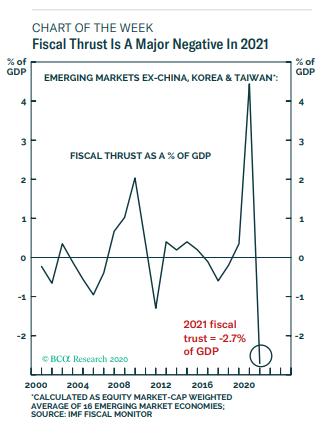

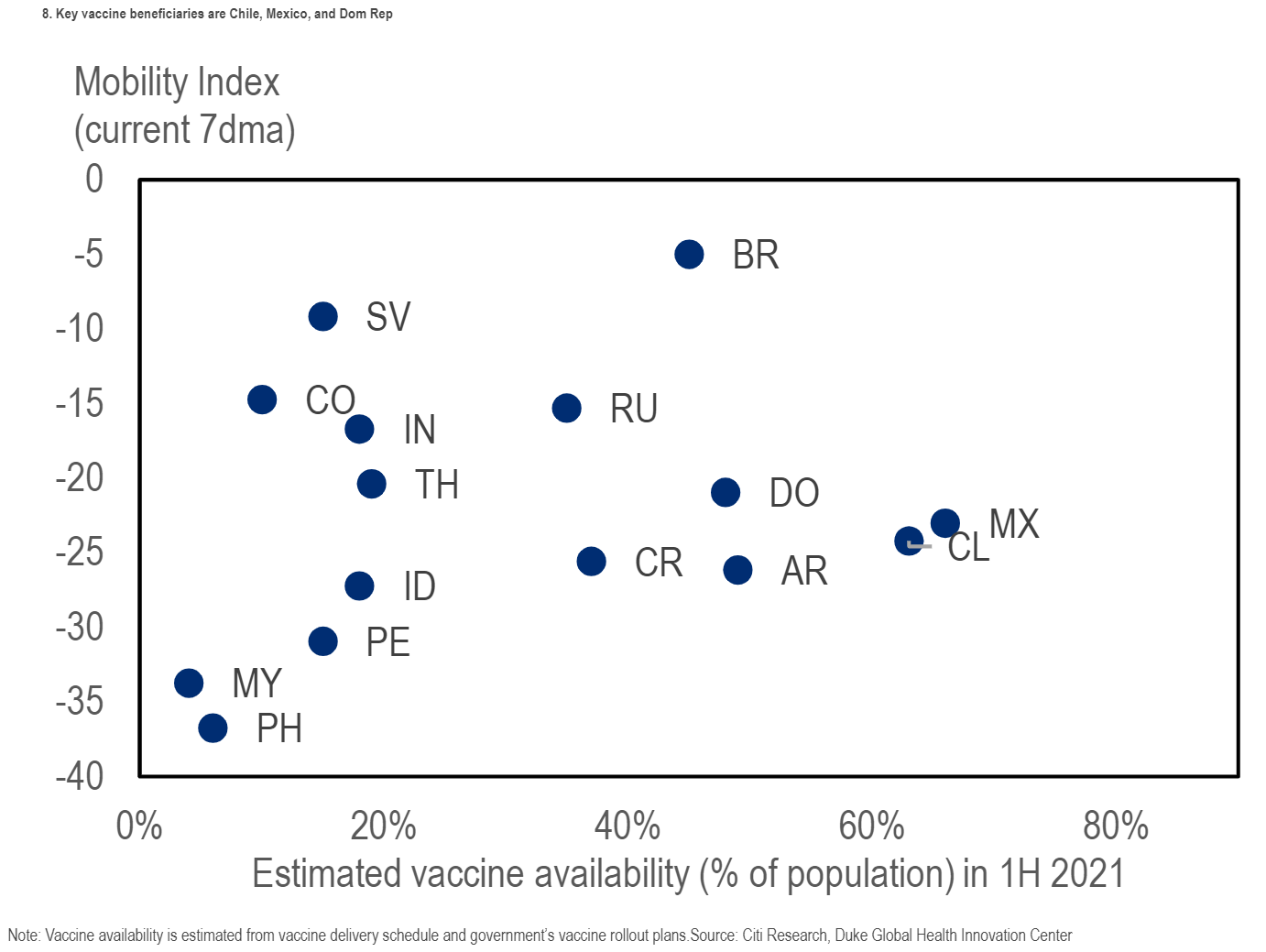

Emerging ConsensusA happy and uneventful year is winding to a conclusion with a series of records. Risk appetite is back, and an array of U.S. stock indexes have hit all-time highs. With investors gaining in confidence, the dollar has dropped, on a broad basis as measured by Bloomberg's index, to approach its low for the Trump era, set in 2018. If it takes out that mark, it will be at its weakest in six years:  There are reasons for greater risk appetite, including the likely forthcoming approval of a second Covid-19 vaccine, from Moderna Inc., and growing confidence that congressional negotiators will thrash out a support package before Christmas for people harmed economically by Covid. But it is the appetite for risk itself that matters. If investors wanted to be more cautious, they could cling to brinkmanship in the Brexit negotiations, disquieting news that people receiving the Pfizer Inc. vaccine are suffering allergic reactions, disappointing U.S. economic data in the last few days, the growing antitrust storm surrounding Google and Facebook Inc., and the frankly terrifying news that a cyber-attack has managed to compromise several U.S. government agencies, including the one responsible for nuclear weapons. To look through that lot, people must feel bullish indeed. Now, the question is whether that undeniable bullishness can move on to buoy an asset class that has been awaiting revival for years — emerging markets. Since the MSCI Emerging Markets equity index began in 1988, its performance relative to the MSCI World developed markets gauge has moved reliably in line with the dollar. A strong dollar, compared to other developed market currencies, means weak emerging markets relative to the developed world, and vice versa. So far, emerging markets haven't picked up as much, in relative terms, as might be expected after a dollar tumble on this scale:  This leaves emerging markets finely poised. Sentiment that they are poised to outperform is almost universal, in line with virtually universal belief in reflation over the next year. And the latest rise in the Emerging Markets index has left it almost equal with its high from January 2018. Pass that landmark, and then it might just be possible to exceed the historic high of Halloween in 2007, when EM peaked after an extraordinary bull market, and began to crash as the global financial crisis set in:  But definitions can be treacherous, and the "Emerging Markets" label is beginning to lose its usefulness. Exclude China, and its infuriatingly volatile stock market, and EM is already at a high; exclude the rest of Asia (and particularly South Korea and Taiwan, which benefit from China's economy but channel its growth through far more developed companies and capital markets) and EM is far below its Halloween peak:  So, where to with emerging markets? Macro Destiny If the prevailing belief about the macro environment is correct, then EM outperformance is close to an inevitability. Falling Treasury yields tend to mean lack of confidence in reflation, and therefore falling emerging market currencies. Treasury yields have begun to turn upward. (The chart is from London's Longview Economics):  When the currencies of emerging markets improve, then their equities start at last to beat the developed world. EM currencies have staged a noticeable revival since the disasters earlier this year:  Then we come to fundamentals. Earnings in emerging markets outside Asia look terribly depressed — although the same can be said of some developed countries in Europe, led by Spain. This chart from Gaurav Saroliya of Oxford Economics shows how badly earnings per share are deviating from trend across the world. It's fair to hope that they can snap back:  For a big extra kicker, note that emerging markets also look very cheap — dramatically so if we look at cyclically adjusted price-earnings multiples, although again, as this chart from Oxford Economics shows, everywhere looks cheap compared to the U.S:  There are wide variations. India appears as expensive as the U.S. with Brazil, despite all its problems, not far behind. Turkey, lacerated by crises, looks very cheap, but so do the U.K. and Spain. As for flows of capital, one advantage is that money going into emerging markets has only recently started to pick up again. There is room for the enthusiasm of retail investors to grow much further (just as it did during the 2002-2007 bull market):  It seems hard on this basis for anyone who is excited about a global recovery next year not to put plenty of money to work in EM. So now let's take a look at the risks: Food prices Perhaps the most significant might come from food prices, which are increasing even as EM inflation as a whole stays low. Fast-rising food prices can be a cause of social unrest, and might also force a change of direction in monetary policy:  The redoubtably bearish Albert Edwards, investment strategist at Societe Generale SA, points out that a spike in food price inflation helped to spark the Arab Spring almost exactly a decade ago. It started with a protest against rising food prices in Tunisia:  Chinese monetary policy China's recovery this year has brought much of the world along with it, and been built, as ever, on expanding credit. As these charts from BCA Research show, increasing "total social financing" — a measure of the volume of credit made available — has tended to overlap with higher metals prices, which in turn help to spark revivals in big producers, including South Africa and many of the countries of Latin America. Chinese financing also tends to lead EM stock prices in general. Will China leave the taps open or will it begin to rein in credit again?  Fiscal policy Fiscal expansion has helped all countries of the emerging world get through this miserable year. The problem is that this thrust (changes in spending and taxation as a proportion of GDP) looks totally unsustainable for the year ahead. Tightening fiscal policy, as implied by this BCA chart, could mess up a lot of calculations:  The virus Amid the excitement over vaccines, the candidate that has so far failed to live up to the greatest hopes, from Oxford University and AstraZeneca Plc, also happens to be the one that was thought most likely to rescue the developing world. It is cheaper, and far easier to store and transport than the rivals from Pfizer and BioNTech SE. Some emerging regions, notably northern Asia and much of sub-Saharan Africa, have been relatively unscathed by the virus to date. Others, such as Latin America and India, have suffered grievously. The following chart, produced by Citigroup Inc., shows how far mobility is depressed, compared to the start of the year, along with estimates on availability of the vaccine by mid-year. Countries that appear lowest and to the left have severely restricted economic activity, and are unlikely to receive much aid from the vaccine in the near future. That is a problem in particular for Malaysia and the Philippines, and also Peru. Meanwhile Chile and Mexico, well positioned to get the vaccine to a large swath of their population, look as though they have the most to gain.  Where does that leave us? If — if — you believe the optimistic inflationary story of a world recovering from the virus in 2021, it is hard not to devote resources to emerging markets. Several of them are so bombed out that they have little downside. This is largely an asymmetric bet of "heads I win, tails I don't lose too much." The critical test remains whether the world really can reflate away from its pandemic slump next year. Survival TipsThe Brexit saga continues to unwind interminably, with yet another deadline coming up this weekend, and British negotiators still trying their hardest to persuade all and sundry that they really are prepared to go through with leaving the EU without any deal. That would mean trading on no better terms than those enjoyed by Australia. It would be depressing, except the latest attempt at persuasion is so ludicrous. It has rather cheered me up. I was struck by a line near the end of the latest story on the Brexit negotiations in the Financial Times. Someone tried their level best to convince my old colleagues that British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is nonchalant about the prospect of "no-deal": Officials in Downing Street say that Mr Johnson is relaxed about the talks failing, joking that British people will be "eating fish for breakfast, lunch and dinner" when the UK takes back control of its fishing grounds. The prime minister is also said to have added to his repertoire of Australian songs — a reference to what he calls an "Australian-style" no-deal exit — humming "Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport" in his office.

Methinks he doth protest too much. Telling the FT that he's singing "Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport" to himself in Downing Street suggests a desperation to appear unconcerned. And can he seriously want to sing a song that awful? If he does want some Australian music to cheer him through the negotiations, I can suggest some other possibilities. There was hope that Johnson could make a decisive change when he took over from Theresa May, but in fact it's a case of new person, same old mistakes, and now he appears to be in deep trouble. Few can possibly believe that Johnson really thinks that life after a no-deal exit would be anything like the prosperity enjoyed in the land Down Under. But still, he is trying to convince us that he is some kind of suicide blonde, bent on driving himself and his country over the cliff of a no-deal Brexit. This isn't some cheap thrill; he really means it. With Brexit, it often feels like we only go backwards, as Brexiteers are lost in yesterday, hopelessly devoted to an imperial power and an absolute version of sovereignty that are no longer available for anyone. As such, it is possible that Britain is stuck on the highway to Hell, and it is better just to let it happen. Some would say the less we know about this the better, but we shouldn't let these issues mystify us. Johnson has been lucky in the past, particularly in his opponents, and presumably hopes that he will be so lucky as to see them fold again. More likely, after burning the midnight oil, he will have to accept a compromise at the last minute. The hype over fisheries suggests the vintage British tactic of claiming victory over Europe via an unlovable piece of British cuisine, such as the sausage.

Meanwhile, Brexit will drag on and on. Don't even dream it's over. Some of the Australian music I linked to is actually quite good. I hope you enjoy, and have a good weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment