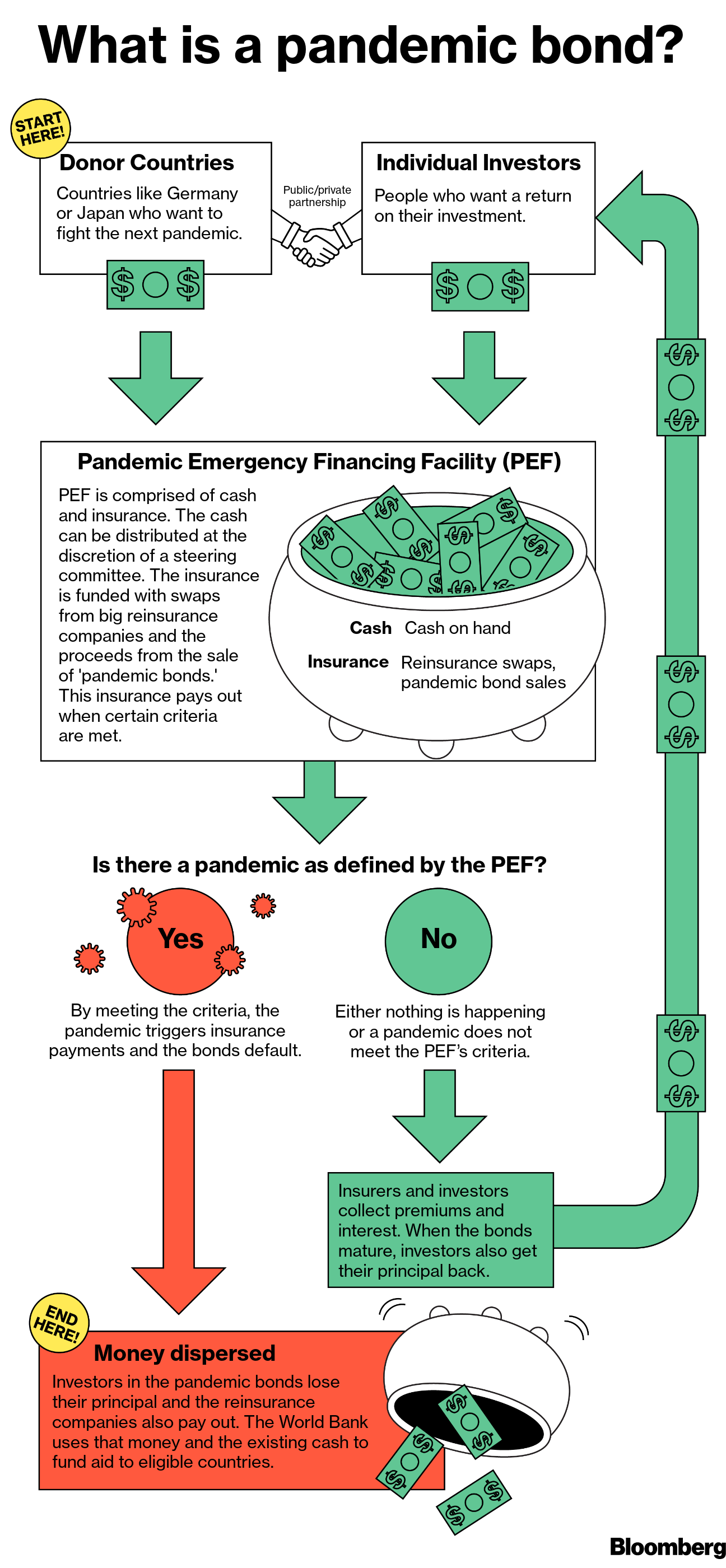

| China ramps up its social credit system. The U.S. sues Facebook. And Tesla is overvalued, according to JPMorgan. China is making swift advances with a system for measuring the social creditworthiness of companies in a sweeping data-collection effort covering foreign and domestic enterprises. Compiling this information is aimed at allowing government officials, banks, suppliers and consumers to check on a company's behavior. Corporate actions could be analyzed, potentially leading to rewards like lower taxes and government contracts or punishments like fines and prohibitions on activities. There's already one blacklist that companies are paying $2,500 an hour to avoid. Here's why foreign firms are walking on eggshells in China. Asian stocks looked poised for declines after U.S. technology giants dragged Wall Street benchmarks lower amid dimming prospects for fresh stimulus. Treasury yields ticked higher. Futures pointed lower in Japan, Hong Kong and Australia. The S&P 500 slid from a record, while the Nasdaq 100 had its biggest slump in a month. The dollar edged up, while gold retreated. Elsewhere, traders were also watching for developments on Brexit amid ongoing talks in Brussels. Crude oil fluctuated. U.S. antitrust officials and a coalition of states sued Facebook for allegedly abusing its dominance to crush competition, the second time in less than two months the government has brought a monopoly case against an American technology giant. The Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general led by New York filed antitrust complaints against Facebook Wednesday, alleging conduct that thwarted competition from rivals in order to protect its monopoly. The FTC lawsuit seeks a court order unwinding Facebook's acquisition of Instagram and WhatsApp. Going forward, U.S. tech giants are facing a bumpy road in the antitrust department. Tesla's shares are now "dramatically" overvalued and investors thinking of raising their holdings in the company ahead of its impending addition to the S&P 500 Index should not, JPMorgan analyst Ryan Brinkman says. The analyst pointed out that in the past two years Tesla shares have risen over 800%, though analysts have raised their price targets by about 450%, and simultaneously lowered their earnings estimates for 2020 through 2024. Brinkman raised the possibility of "speculative fervor." He raised his price target on Tesla to $90 from $80, citing the $5 billion at-the-market offering announced Tuesday, and maintained the sell-equivalent rating. The company's stock dropped as much as 2% to $636.63 in New York on Wednesday. The optimism on display just two months ago when Singapore Transport Minister Ong Ye Kung pledged to reopen the city-state and its tourism-reliant economy has taken a beating after a suspected coronavirus case was found aboard a cruise ship. In the early hours of Wednesday morning, the 1,680 passengers on Quantum of the Seas and 1,148 crew were alerted to an announcement that a suspected case of Covid-19 had been discovered, and the voyage was cut short. It was the second blow in as many months after a highly anticipated air travel bubble with Hong Kong was axed before it even started. What We've Been ReadingThis is what's caught our eye over the past 24 hours: And finally, here's what Tracy's interested in todayWould you like to read 3,000 words on pandemic bonds? I think you should. Created by the World Bank a few years ago, they operate like catastrophe debt, which pays insurance claims on natural disasters. Pandemic bonds touch on some of the big economic and financial themes of the Covid-19 crisis, a key one being the question of who should foot the bill—the government or private entities such as insurers? Pandemic bonds were a public-private partnership between the World Bank and a group of investors and insurers, intended to share the financial burden of responding to major disease outbreaks. The World Bank would pull in extra money from investors that would become available to help fight a pandemic if certain criteria were met, such as a rise in cases or deaths caused by a virus such as Ebola or Covid-19. Ultimately the bonds helped divert $195 million to the fight against coronavirus. But the money from investors was really a drop in the bucket compared to the amount needed to combat the biggest pandemic in more than a century, with the World Bank planning to spend $160 billion over 15 months.  Bloomberg Bloomberg The sheer scale of the pandemic and its effects may spark wider acceptance of the role of government in backstopping economic and social crises, shifting attention away from private market solutions. We've already seen that play out in a number ways, as more heterodox strands of economic thinking that advocate for a much larger role for government spending become popular on Wall Street. The problem with a bigger role for government spending is that it tends to involve politicians. And, as we've seen this year with the U.S. stimulus bill, political grappling over how the government should spend its money means the backstop can be delayed or come in too small to make much of a difference to an unfurling economic crisis. For that reason, economists like Claudia Sahm have been advocating for "automatic stabilizers" that could bypass bickering politicians. Such stabilizers would automatically boost spending if certain triggers are met, such as the unemployment rate jumping above a certain level. Pandemic bonds attempted a similar thing, spelling out very specific conditions that would trigger a writedown on the debt so the money could be diverted to the World Bank to fight the outbreak. But the pandemic bonds show just how hard it can be to calibrate those triggers. As I write in the story, "In an effort to avoid political grappling over donor funds, the pandemic bonds relied on mechanical triggers that failed to fire." Do give the whole thing a read. |

Post a Comment