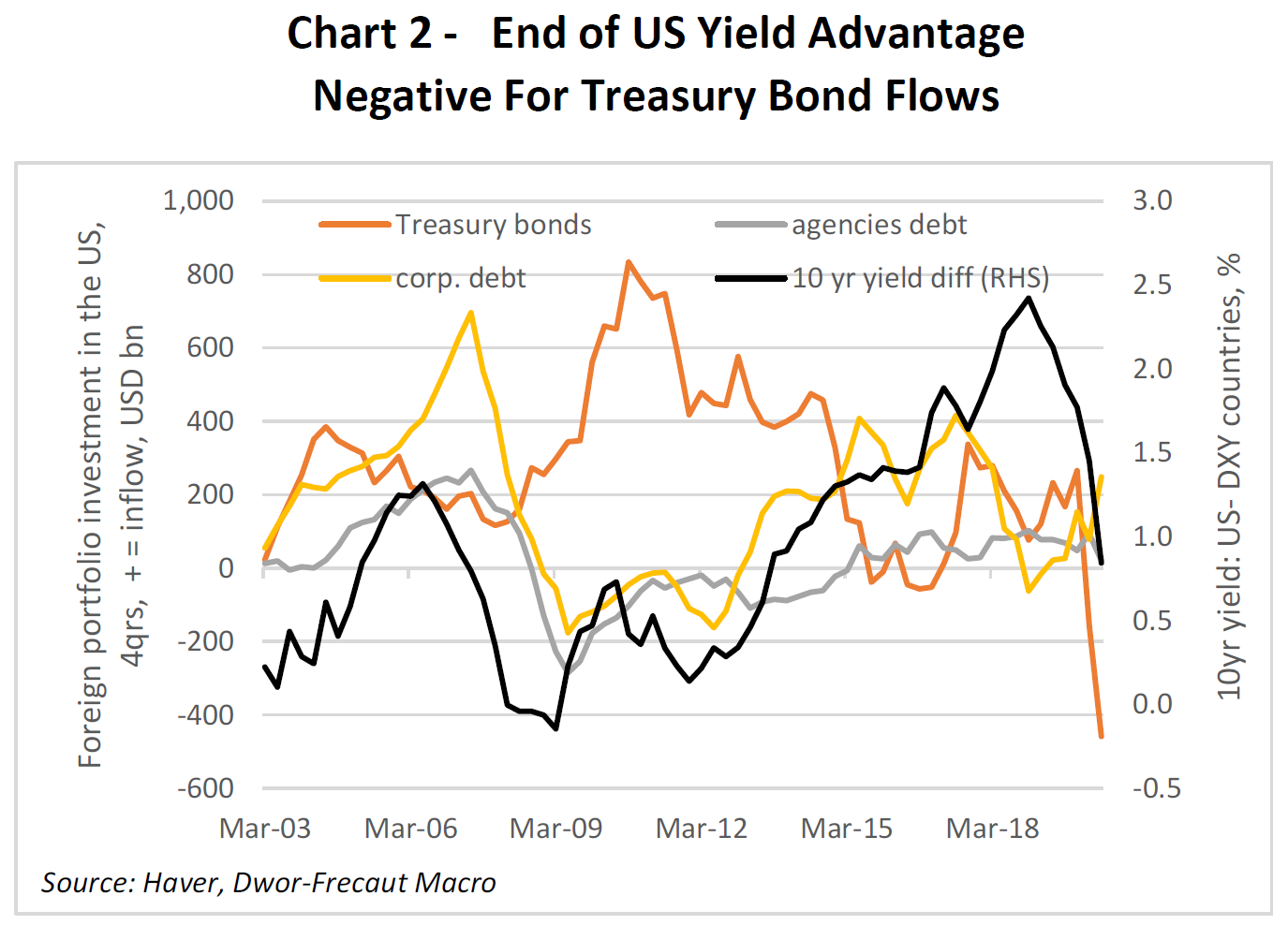

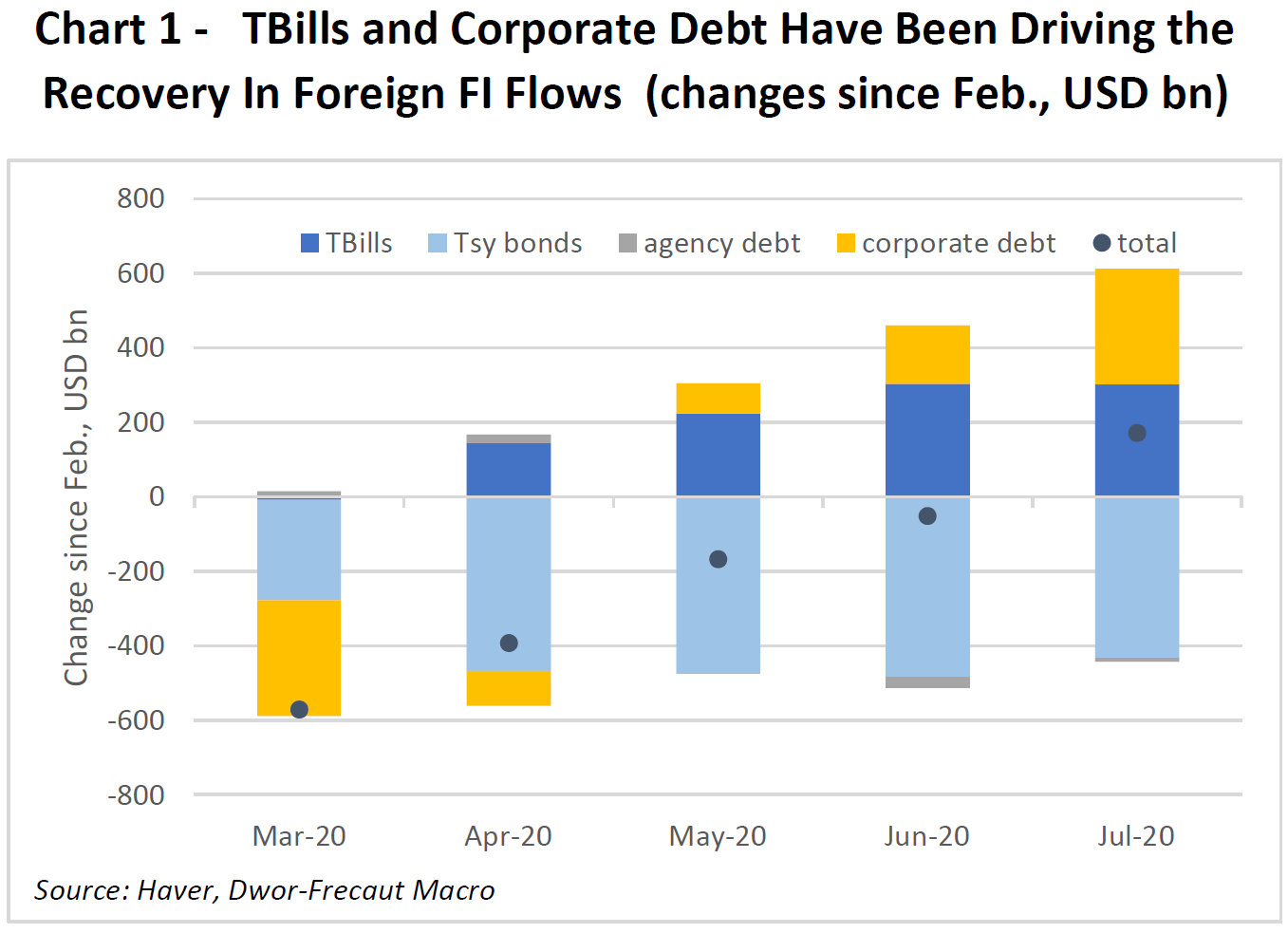

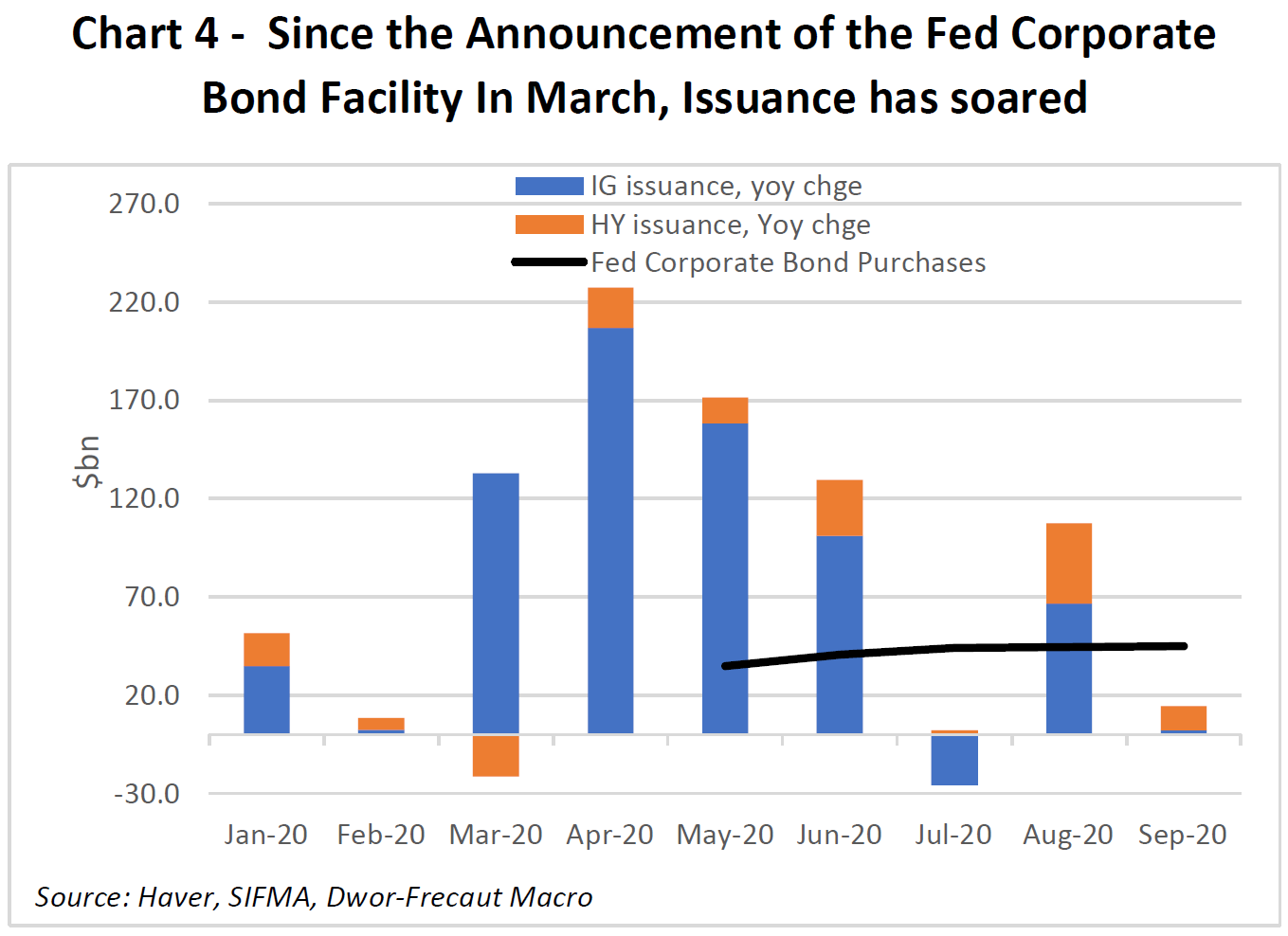

How was the play, Mrs. Lincoln?This newsletter may well read like a long attempt to console Mrs. Lincoln and take her mind off the horrors of American politics by asking her about the play she's just seen. But at the beginning of a week that will be dominated by U.S. political drama like none in decades, it is necessary to remember that many other momentous trends are playing out around the world. Before politics takes over, here is a reminder of what else is on our plates. Real Yields and Central BanksAhead of meetings by the Federal Reserve's Federal Open Market Committee on Wednesday (which is unlikely to produce much of note, particularly given the political circumstances), and by the central banks of the U.K. and Australia (both of which are expected to see some kind of easing) on Tuesday and Thursday, it's as well to note that the bond market appears to be turning. In the wake of the Covid shock, real 10-year yields, after accounting for inflation expectations, dropped below minus 1%. Since the low Sept. 1, they have regained some 25 basis points:  The last great trough for real yields, in 2012, came when markets were convinced that the Fed would keep supporting bonds forever through what was then known as "QE-Infinity." They wobbled higher for a while, the gold market cracked (as confidence in currency debasement was lost), and then real yields shot upward during the so-called Taper Tantrum, after the then-chairman of the Fed, Ben Bernanke, started talking about the possibility of tapering asset purchases. This time around, inflation breakevens have dropped slightly since making a high Sept. 1, while nominal yields have risen. The results of the election could have a big impact, with a "blue wave" likely to be greeted by higher breakevens and nominal yields. But whatever the outcome, it will be hard for real yields to go negative by more than 1% again, unless the Fed decides that it is determined to send them there. This becomes critical to watch. Meanwhile, it is now six months since the Fed's unprecedented actions to stave off the crisis in March, and some unforeseen consequences are beginning to grow apparent. One, pointed out by the independent macroeconomist Dominique Dwor-Frecaut, is that the flow of foreign money into Treasury bonds has fallen sharply. That is partly because the great advantage in yield that Treasuries enjoyed over German bunds and other rival "risk-free" investments has been greatly reduced, and partly because corporate bonds offer much more appealing competition now that the Fed is backstopping them:  Indeed, in the months since the March implosion, there have been net flows of foreign money out of Treasury bonds, although these have been counterbalanced by flows into T-bills and corporate debt:  Thanks to the Fed making corporate bonds more appealing, issuance has boomed since March:  This helps to explain why the dollar hasn't suffered more over the last few months. Looking at the Treasury market, it appears to have lost much of its yield advantage; but the Fed, by creating a vast new supply of debt with a government backstop and with higher yields than Treasuries, has managed to keep flows coming into the dollar. This could yet create issues for Uncle Sam if and when the time comes to raise debt for a fiscal expansion. Meanwhile, the Fed's support for corporate debt has had another major impact, on banks. Crowding Out Bank Loans: Liquidity-Driven Bond Issuance by Olivier Darmouni and Kerry Siani of Columbia Business School goes into the new appeal of corporate debt, and reaches the same conclusion as Dwor-Frecaut: corporate bonds represent an ideally positioned asset class: they balance (1) investor demand for safe assets and (2) reach for yield. First, corporate bonds, particularly issued by highly rated firms, have limited downside. The Fed's stated support helped buoy the safety of corporate bonds further. At the same time, these bonds pay a high spread over Treasuries, providing an attractive alternative for safe investments in a time when interest rates are at historical lows.

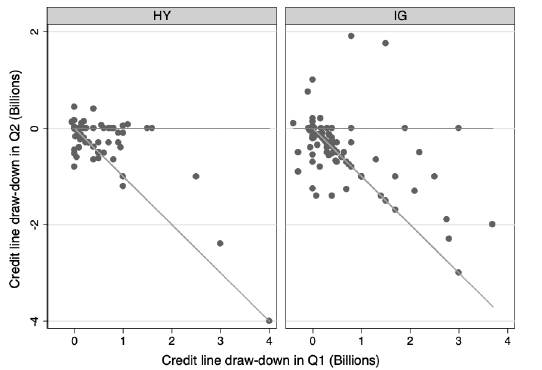

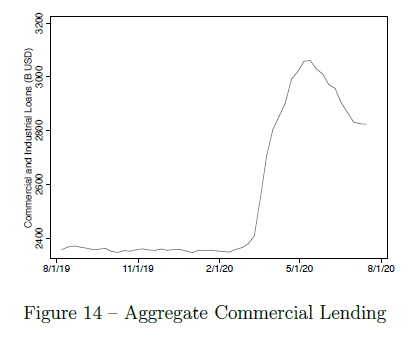

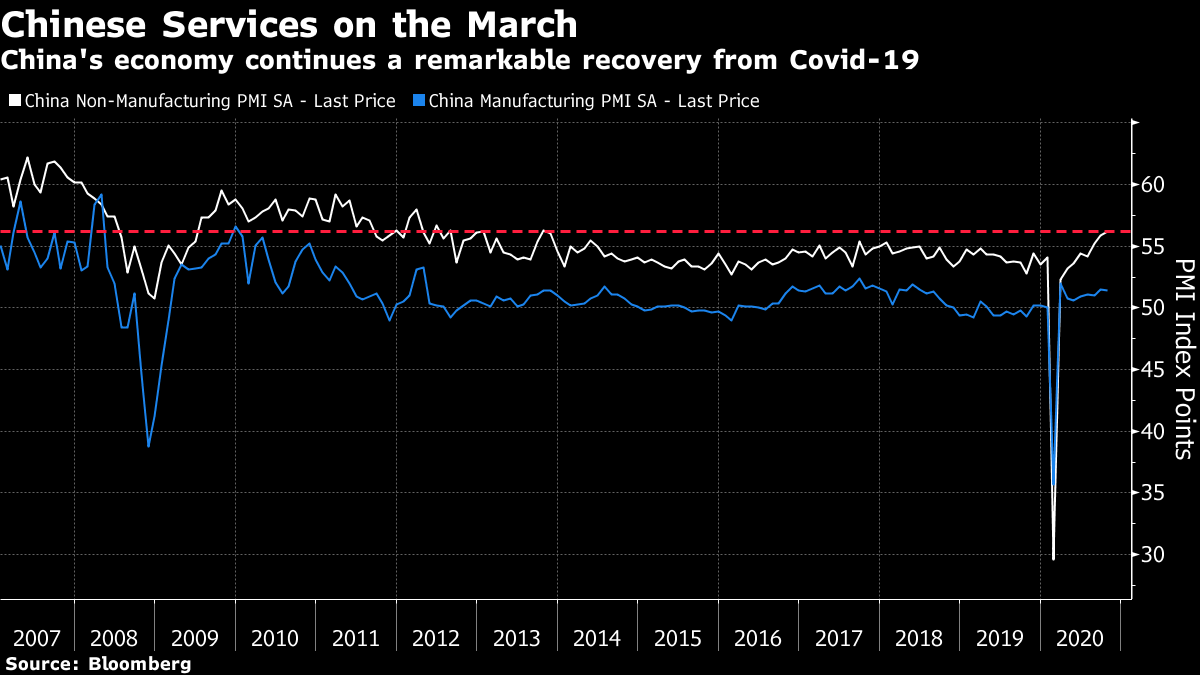

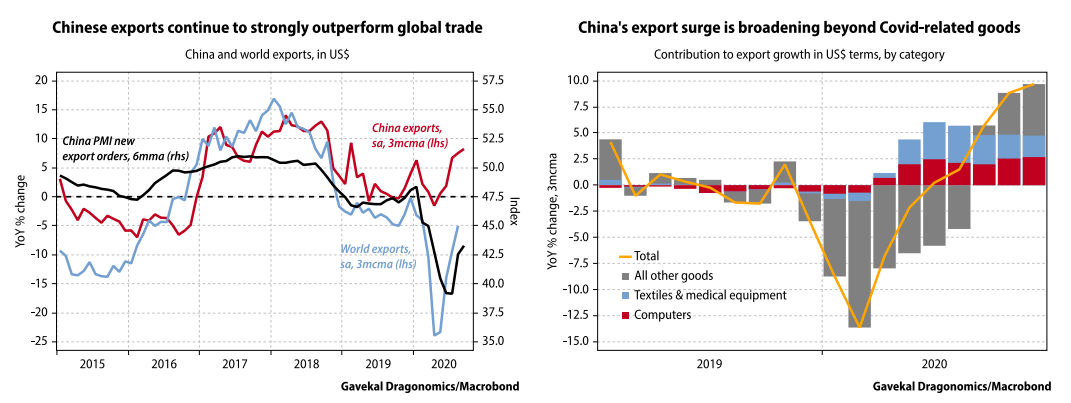

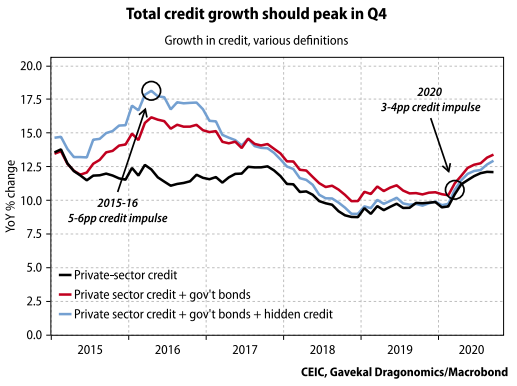

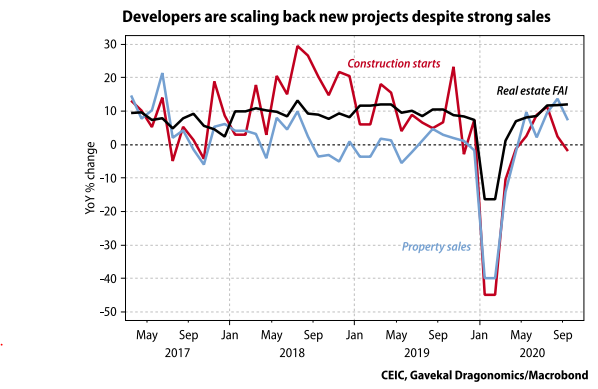

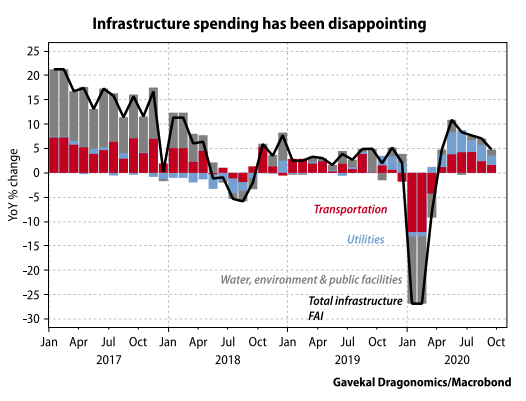

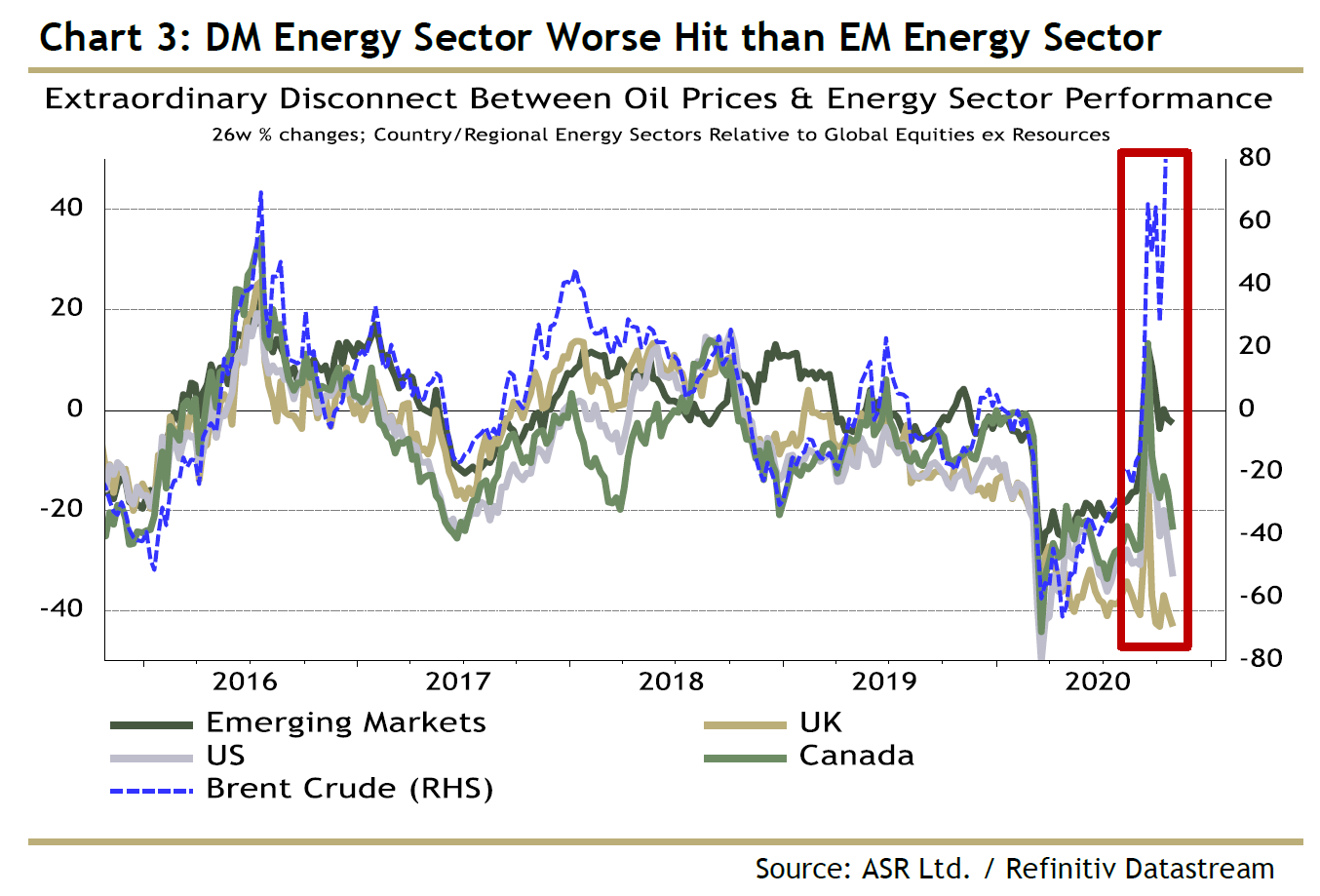

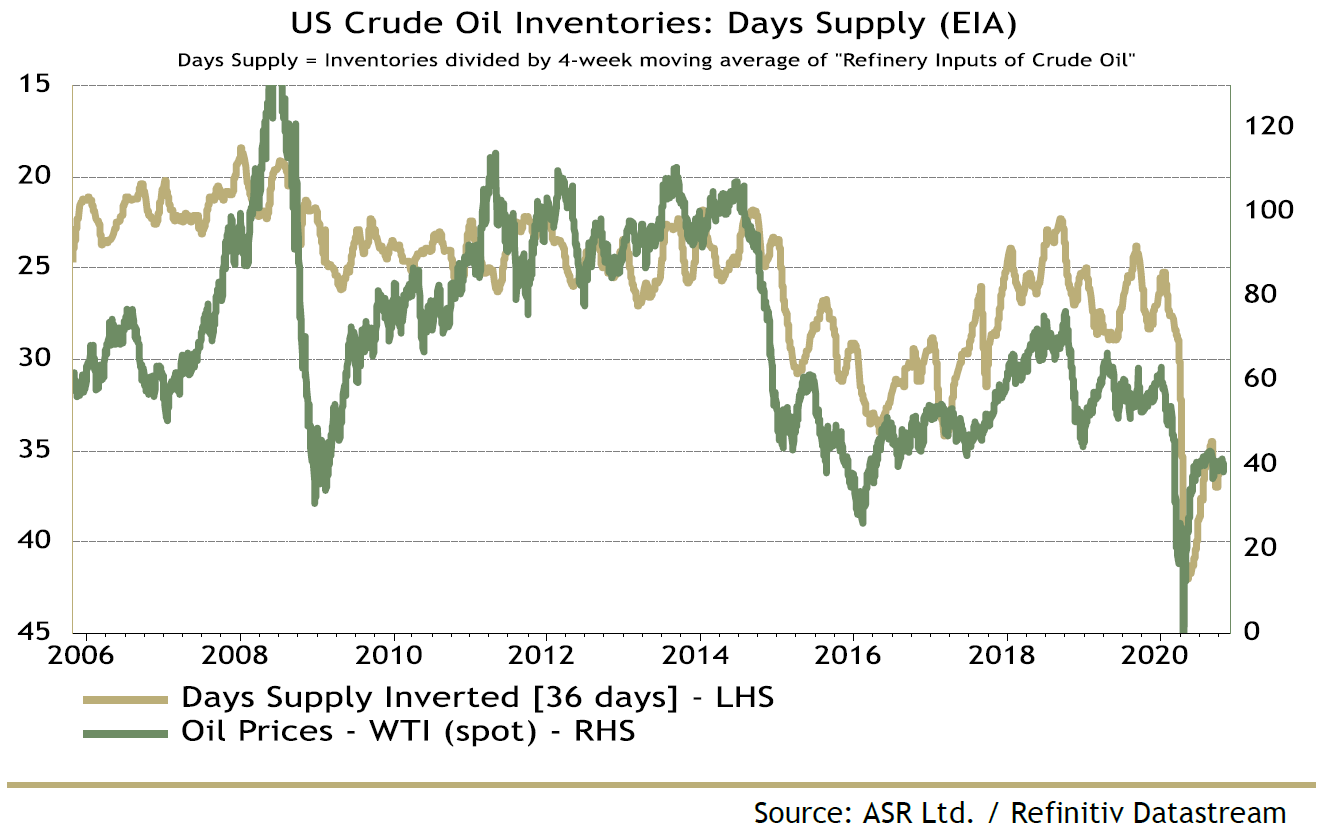

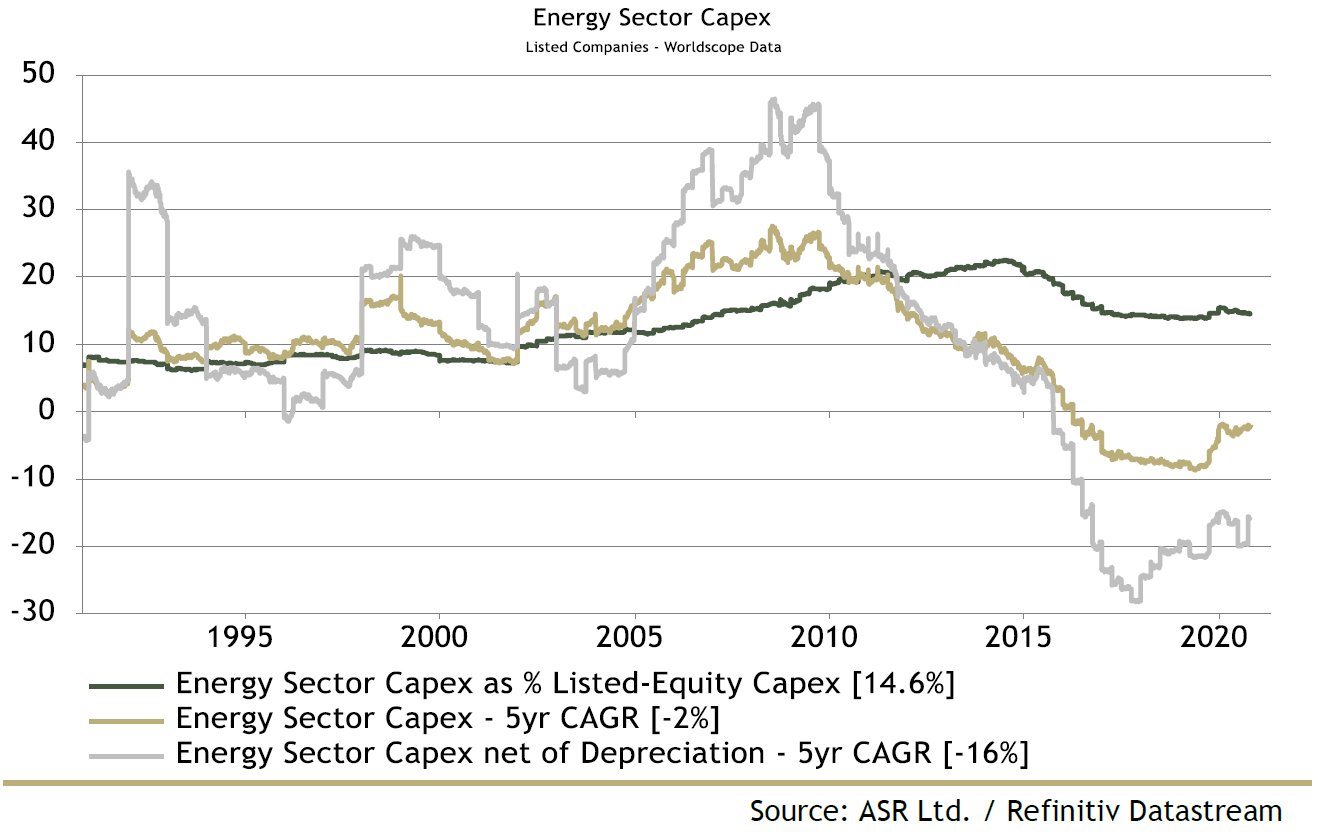

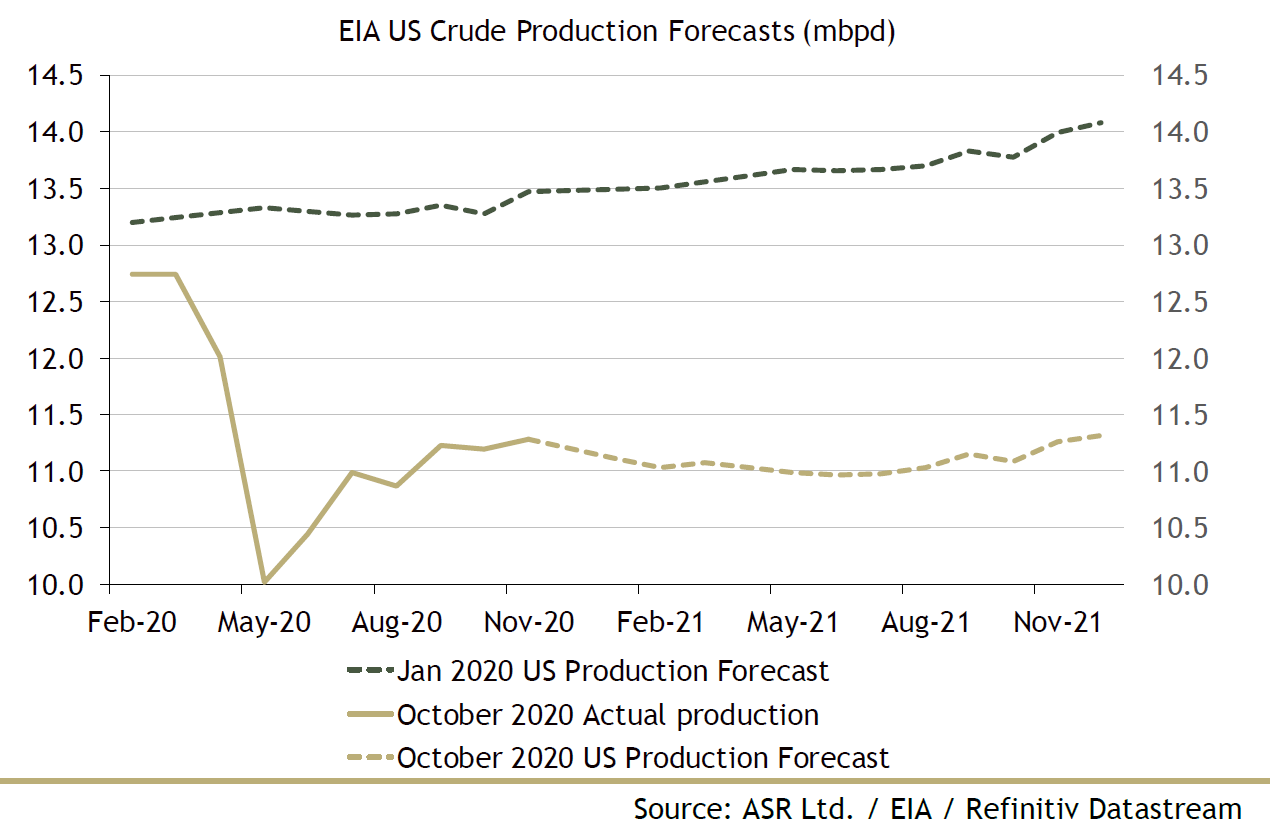

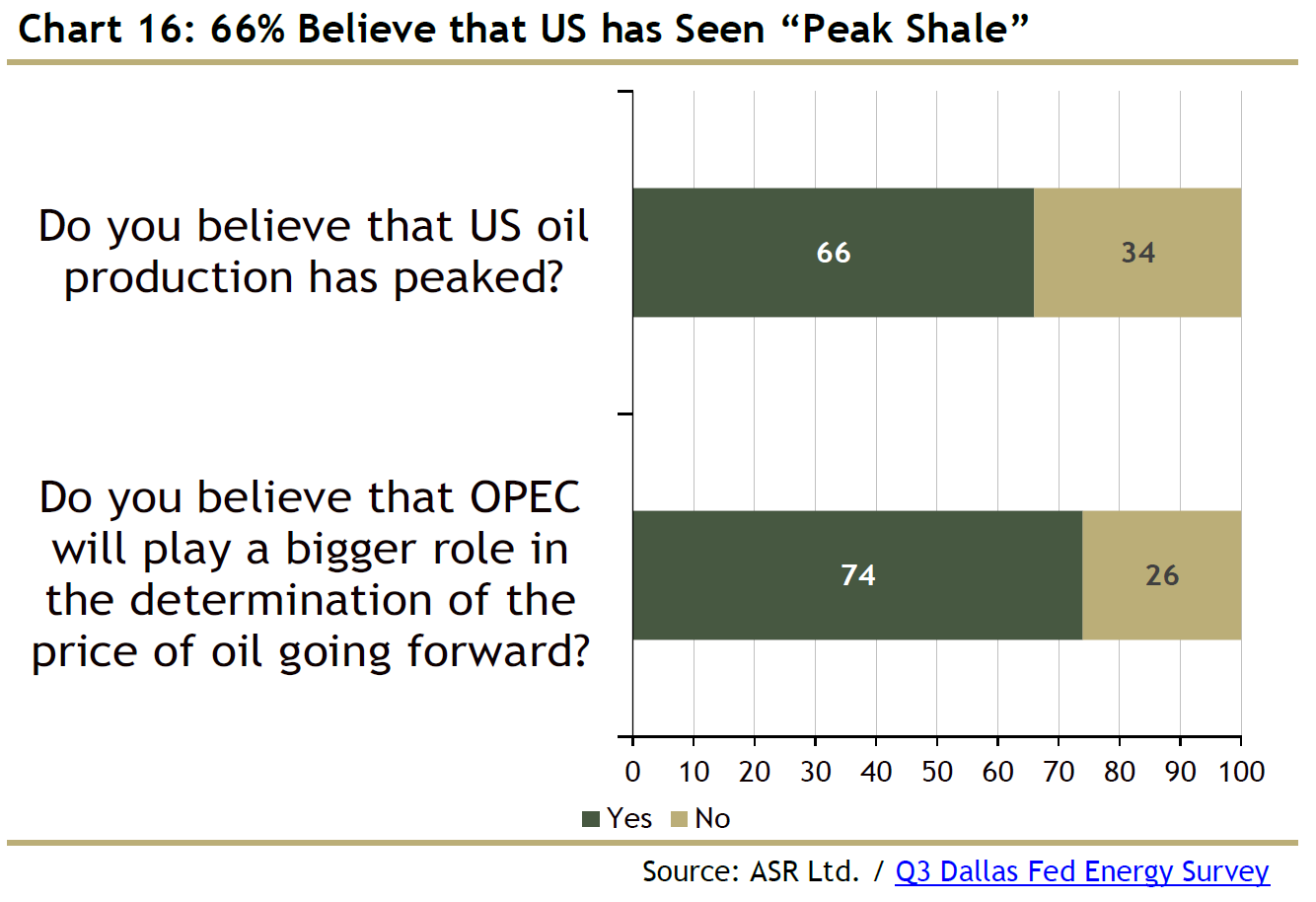

Meanwhile, with their yields falling, they offered a very attractive alternative for corporate borrowers. So it was that in both the first and second quarter, during a historic liquidity crisis, only a tiny number of corporate creditors opted to draw down their credit lines with the banks. The great majority opted to pay them down:  While commercial and industrial loans rose rapidly as the Covid shock took hold, aggregate loans started to reduce as early as May:  According to Darmouni and Siani, more than 40% of bond issuers left their credit lines untouched in the first quarter, while they used a large share of bond issuance to repay bank loans. This "liquidity-driven bond issuance" brings into question the long-held assumption that banks have an advantage providing liquidity in a crisis, and means further problems for the traditional banking business model. It also suggests that the V-shaped recovery of bond markets, propelled by the Fed, "is unlikely to lead to a V-shaped recovery in real activity." The Fed's corporate debt backstop did indeed help to avert a liquidity crisis, then. But it has crowded out banks, and done little to spur any growth in real activity. Such questions will come before the FOMC on Wednesday afternoon — even if political drama elsewhere in Washington may be hogging the attention by then. China Monday will see supply manager surveys from around the world, which will give a good "tell" on the extent to which the latest wave of coronavirus cases is affecting the economy. They matter. PMIs from China are already available, and they are emphatic:  China's services sector is posting the strongest performance, on this measure, since 2013, while manufacturing is also showing a robust recovery. The rise in services is important, because China was already demonstrating that it was able to reactivate its old model, based on manufacturing and exports. As Gavekal Dragonomics illustrates, Chinese exports are rising far faster than global trade as a whole, and in the last few months have expanded from a previous reliance on tech and Covid-related products:  Meanwhile, the credit stimulus that it has taken to achieve this, while significant, is on an altogether smaller scale than the desperate splurge of lending that tided China through its 2015-16 crisis, when a botched devaluation briefly shook confidence around the world:  It is true, as Gavekal shows using Chinese government data, that the country is using some of the old playbook. Real estate investment took off after the Covid-driven downturn earlier in the year — much as has been seen in the U.S. But the current leadership seems nervous about this, and construction starts have already been reined in again:  Meanwhile, in what might be another portent for other countries once they finally put the pandemic behind them, infrastructure investment has been somewhat disappointing. Following the sharp fall earlier in the year, it is now running ahead of 2019, but not by enough to make up for its earlier dip, and the rate of growth is declining again:  In this context, the strength of the Chinese services sector seems to confirm that the country is managing to move on to domestic demand growth, after successfully using exports to help drag it out of its problems earlier in the year. The global economy isn't a zero-sum game, and China's success in righting itself is good news for the rest of the world; but its recovery will pose difficult problems for the next U.S. president, who must decide how to respond. OilCrude prices ended last week at a four-month low, and with a further fall in early Asian trading Monday they stood more than 20% below their late August high — enough to satisfy standard definitions of a bear market. Following the sharp rebound from their disastrous freefall earlier in the year, prices had tailed off far earlier than many in the industry had hoped, and without ever arresting the steady decline in shares of global energy companies compared to the rest of the market. The extent of the selloff in energy stocks, while oil was recovering, has been startling:  As the following chart from London's Absolute Strategy Research Ltd. shows, the failure of the crude price to raise oil stocks is very unusual, and has been most pronounced for the multinational players of the U.S. and, particularly, the U.K.:  Beyond the politics of supply, crude inventories in the U.S. haven't declined by much, which increases the problems for the oil price:  For the longer term, capital investment in the energy sector has reduced substantially over the last decade, suggesting in the long term that this will deal with the problem of overcapacity and begin to limit supply. It also, however, demonstrates why the energy sector isn't creating as many jobs as it once did:  Meanwhile, the U.S. may have a specific issue with shale production, which has of course been a major issue in the presidential campaign. Production forecasts have been slashed since the spring, and no great expansion is anticipated next year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Association:  This implies bearishness about the future for shale, which requires a high oil price to be economically viable. Absolute Strategy quotes the Dallas Fed's third-quarter energy survey, which found that two-thirds of energy executives thought that U.S. oil production had peaked ("Peak Shale"), while roughly three-quarters believed that the OPEC cartel would begin to play a bigger role again.  Whoever wins the presidency, the shale industry is unlikely to revive with the price of crude back below $40 per barrel. The oil market is no longer as central to American and European politics and economics as it was in the 1970s, but it cannot be ignored. Survival TipsIt's hard to imagine tension much higher than at present. So here is another suggestion for some "respite" music to help get through this week. It is more than 60 years since Miles Davis recorded Kind of Blue, with a band including John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley. Very experimental at the time, it is the most hypnotic piece of music I know; transcendent, beautiful and serene. It's not something that ever grows dull. I still don't understand why it exerts such a hold, and the musicians themselves seemed amazed that it became the most popular album in the history of jazz. If you don't know it yet, I strongly recommend listening and letting it get under your skin this week. If you already know it, I've included links to a documentary and some live performances that I hope will be of interest. Have a good week, stay chill, and be careful out there. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment