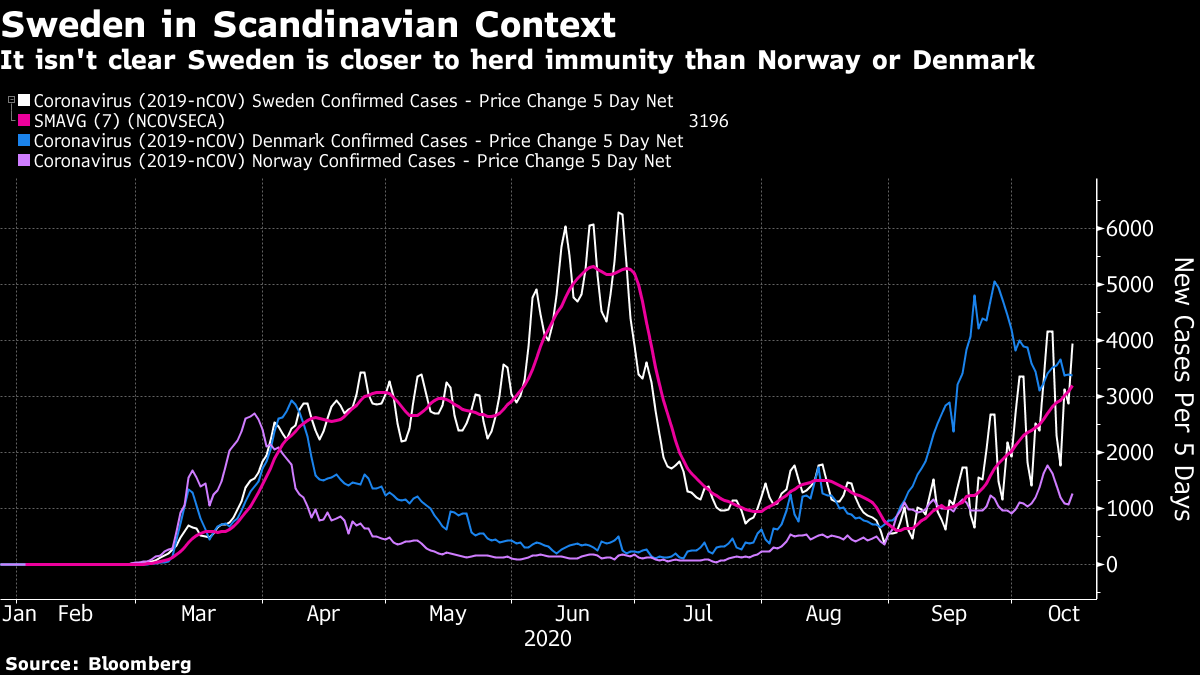

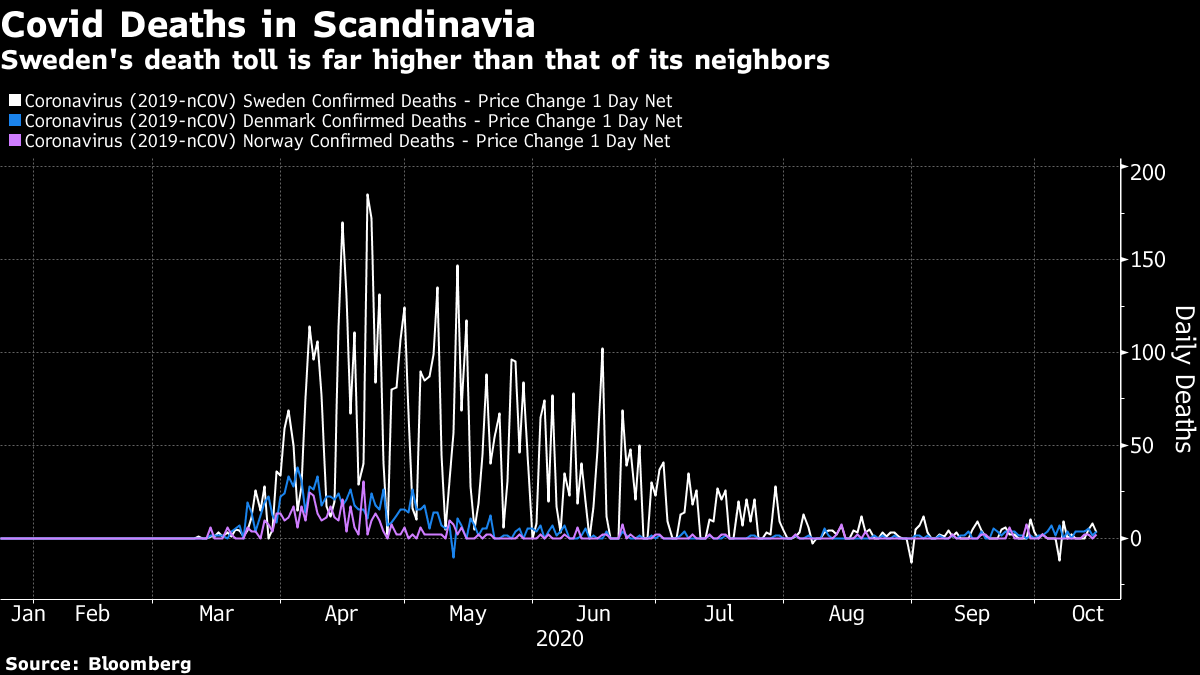

Coronafeedback Last weekend, I hit everyone with my latest essay on the morals of the coronavirus, this time on the issue of whether it is morally justified to aim for herd immunity via infections, using the system of "focused protection" advocated by a group of epidemiologists in the "Great Barrington Declaration." It provoked more than the usual feedback, which isn't surprising. After all, this personally affects all of us. So here are some of the main points of discussion that have emerged. Morals On the ethics of the issue, the longest and most detailed debate took place here on LinkedIn. There is another here. I was sent one fascinating contribution from a Catholic priest arguing passionately against lockdowns (as far as I am aware this isn't the Church's official doctrine). I was also urged to include the ideas of Emmanuel Levinas, a 20th century French-Lithuanian philosopher who based his ethics in "the vulnerability of the other," to whom we owe the greatest responsibility. I was also chided for missing out philosophers of virtue, starting with Aristotle. A group of epidemiologists published this riposte to the Great Barrington Declaration in the Washington Post, stating flatly that the approach their colleagues are suggesting could lead to millions of deaths. There is also plenty of commentary on the backing for the declaration from right-wing libertarian groups, and for the plethora of joke signatures that have been added to their online petition. You can read this great anthology by Brooke Sample for a round-up of the commentary Bloomberg Opinion has published on the dilemma. I think it's for everyone to immerse themselves in the discussion. It isn't clear to me who's right. But to be clear, there isn't a good option. We are choosing between a number of unpalatable possibilities, and a number of alarming risks. It would be nice to magic up a vaccine, but that is easier said than done. Sweden One place that comes up again and again when discussing herd immunity is Sweden, the country that has effectively followed the policy the Great Barrington academics are proposing. As the comments under my essay from last week make clear, Sweden's record can be viewed to reflect whatever you want it to. Many evidently believe that the Swedish experiment in herd immunity has already been proved right. It is way too soon to say that. Much of the rhetoric favoring Sweden rests on comparing its record with the U.S. The two countries have had much the same death rate, even though Sweden has never closed its schools. Evidently this makes the U.S. look bad, but it's not clear that it shows Sweden has done something the rest of the world should want to emulate. Compare Sweden to its Scandinavian neighbors, and its record doesn't look good. This is the record on cases (showing rolling five-day totals):  To be clear: Sweden has a slightly larger population than its neighbors, so I multiplied the Norwegian and Danish numbers to give the death totals they would have suffered had their population been the same size. Obviously, Sweden had far more infections during the summer. Denmark then suffered a growing outbreak in September — but the growth in Swedish positive tests in the last few weeks must call into question whether the pain it went through earlier this year has given Sweden any great advantage. If we look instead at daily death tolls (again multiplying the Danish and Norwegian totals so they are comparable), the picture is brutally clear:  Covid has taken far more lives in Sweden. There are explanations for this. The country failed to protect its elderly in care homes early in the epidemic. But these numbers make it very hard to say that the Swedes have done something particularly clever. What can we say about the economic impact? Governments don't need to decree lockdowns to have a dampening effect on economic activity. The most immediate impact of the lockdowns earlier this year was on employment. So, here are the unemployment rates for the three countries:  Evidently Sweden entered the lockdown with a worse problem than its neighbors. But it is very hard to say that the country gained any great economic advantage for its workforce by eschewing lockdowns. The spike in Swedish unemployment looks identical to the spike suffered by its neighbors. In the (unlikely) event that a vaccine were made available to the entire Scandinavian population tomorrow, it seems to me that the Swedish approach would have been proven wrong in hindsight — more deaths, more people dealing with the after-effects of Covid-19, and no great economic benefit. If we wait another year for the vaccine, it remains perfectly possible that the Swedish approach will look much better, as other countries resort to fresh lockdowns. For a subtler examination, Adam Patinkin of David Capital Partners LLC in Chicago, whose work I featured last month, points to a number of problems with comparisons between Sweden and other countries. He mentions that Sweden had an abnormally lenient flu season last year; that it has a liberal definition of Covid deaths; and perhaps most importantly that Sweden's "all-cause" mortality is lower than usual this year, while neighboring Finland's is higher. It is possible that other countries have sped deaths for other reasons by locking down. Even in the U.S., there remains a case that herd immunity is growing close. Former hedge fund manager Whitney Tilson publishes regular updates on the course of Covid-19, citing numerous sources. His latest is optimistic. A third wave is under way in the U.S. but crucially it is happening in parts of the country that didn't suffer a wave of infections before, such as the prairie states and the Upper Midwest. There is no such severe outbreak in places that have already had one, such as New York City. This suggests that they have reached a "break-point" where the disease finds it much harder to spread. In non-medical language, this makes the case for optimism that the end is near as well as I have ever seen it made. It's fair to say there is still no proof that this optimism is justified, or that Sweden's approach has worked better than others. It's still too soon to tell. But the case for optimism is stronger than it appears from current headlines. A Rejoinder and a Simplification Finally, there was one recurrent criticism of me to which I want to reply. People don't think it should be necessary to look to academic philosophers in universities to make up our minds. We should make up our minds ourselves. To this I would reply that the basics of moral philosophy shouldn't stay in universities but should be shared far and wide, which is what I'm trying to do. To some extent the complaint people are making comes from Marx: "The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it." Academic philosophers have come up with different ways to help us make difficult moral and political choices. Covid has provided us with a classic example of where some clear notions of how to make moral choices would have helped us all. Finally, a simplification. Reading through the reams of proposals, and looking at what actually happened in Sweden, the different sides are nearer than they appear. Everybody says that the vulnerable should be protected, and nobody thinks big gatherings are a great idea. The debate is along a continuum. The more we restrict the movements of the elderly and the others who are particularly at risk, the more the rest of society can behave as normal. The Swedish or Great Barrington approach involves encroaching more on the rights of the elderly, and in return impinging much less on the rights of those younger, particularly school children who have been particularly badly affected. Deciding where we arrive on that continuum needs to be informed by science. It still appears to me that it's ultimately a moral decision. Two readers made specific points against ESG investing and the concept of stakeholder capitalism, much featured in this newsletter this week, and I'd like to respond. The first (with expletives deleted) goes as follows: Balloon punctured by one searing query " When a company needs capital who will come through - shareholders or stakeholders?" End of story This isn't as good an argument as it appears. To continue with some other questions in the same vein: - "When a company needs more revenue, who will come through — shareholders or customers?"

- "When a company needs more productivity, who will come through — shareholders or employees?"

- "When a company needs to secure its supply chain, who will come through — shareholders or suppliers?"

And so on. Shareholders are important, and capital is important. But a company has obligations to, and needs things from, a wide range of other stakeholders. I don't think this is an argument against stakeholder capitalism. Second, there is the separate but related issue of whether companies should give to charities. Milton Friedman in his famous article arguing that companies' sole aim should be to make profits for shareholders also argued that charitable giving should be a decision left to the shareholders with the money paid to them by the company. That leads to the question: Friedman's article touched on another topic . How do you feel about the CEO of Disney using corporate funds NOT his own to send Black Lives Matter $5 million? This isn't the time to discuss the rights and wrongs of the Black Lives Matter campaign, or the specifics of Disney Co. Is a donation to a controversial political campaigning group something that a company should in principle be allowed to do with shareholders' money? On balance, I think it is, but any shareholders who dislike this (of whom I imagine there are many) should certainly be able to bring motions condemning such a donation and stopping them in future. Why should it be within bounds for companies to do this? Companies are legally people, and they have reputations, and they are often regarded as good or bad corporate citizens. They cannot avoid issues such as this. In the case of Disney, with an embarrassing history on race relations (they brought us The Song of the South after all), and with a critical need to appeal to the young, it is probably within their enlightened self-interest to make such a donation. It's certainly controversial; but as a matter of principle it seems to me that they should have the right to use shareholders' funds in this way. Survival Tips It's been a long week. Here is more music for when you need to hit the panic button. Rachmaninov's Vespers, an hour-long a capella piece, is among the most demanding works in the choral repertoire. It's also sublime. It sounds great with only eight singers; perhaps particularly this movement, which Rachmaninov wanted played at his funeral, and involves a fiendish dive into the depths for the basses at the end. It also sounds great with a bigger choir, such as the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir. (That's four Estonian musical links in a row, for those counting). And it's also tremendous with a massed choir. For moments of stress, it has few equals. Have a good weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment