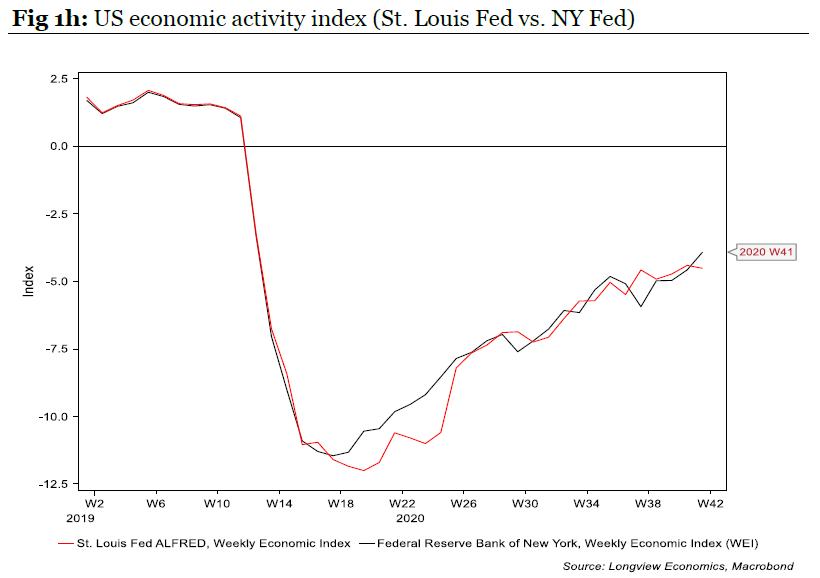

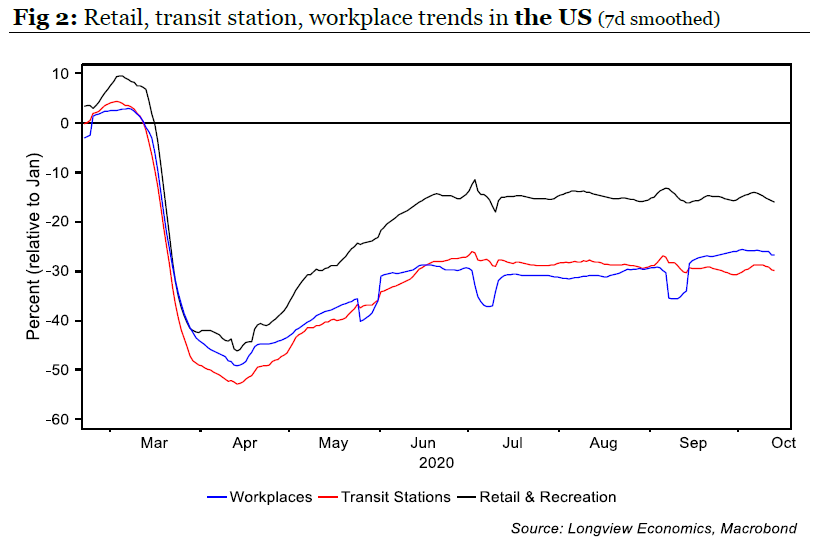

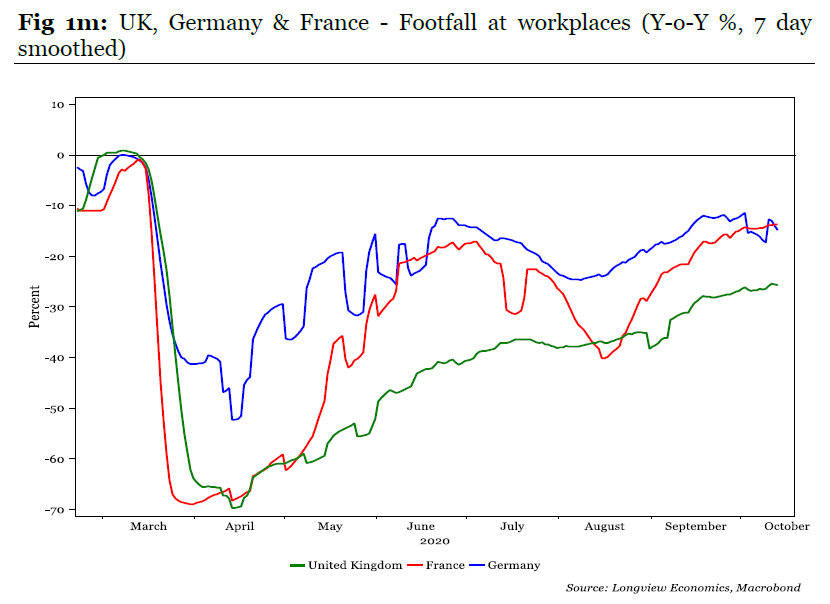

Pandemic Equanimity Covid-19 never goes away. Monday, a generally calm day for world markets, nevertheless brought the news that Ireland is locking down in the face of a fresh outbreak, while the world awaits what could be a crucial hearing of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Thursday that will consider whether any vaccine candidates are worthy of emergency approval. The moral and scientific debate over whether to abandon lockdowns as a strategy intensified. Whatever else has been achieved by the "Great Barrington Declaration," by a group of scientists urging that the virus should be allowed to spread freely through the less vulnerable population, it has prompted the majority of scientists who disagree with them to make their arguments public. John M. Barry, author of a critically hailed book on the Spanish Influenza of 1918, wrote an op-ed for the New York Times arguing that the policy could cost a million or more preventable deaths. There is now an oppositional John Snow Memorandum arguing against the Great Barrington Declaration, and signed by a group of high-powered scientists. It argues that letting the virus spread would "overwhelm health services" while there is no proof that immunity after infection would be durable. Within the political debate, President Donald Trump now argues that Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and previously his chief scientific adviser on the pandemic, is a "disaster" and an "idiot." In rallies, he has levied the charge against his Democratic opponent Joe Biden that he would "listen to the scientists." While this goes on, the Centers for Disease Control has issued a "strong" order to wear masks on public transport, following a tweet from the medical adviser who currently seems closest to the president starting "Masks work: NO." Meanwhile, on both sides of the Atlantic, traditional and more modern measures of activity show that economies have been stuck at a level significantly below normal for some months. The following charts come from Longview Economics in London. The improvement in U.S. economic activity, as measured by the St Louis and New York Federal Reserves, has been steadily tailing off for some months now, and remains well below its level before the pandemic:  Much the same pattern is visible in mobility data for the U.S. After a sharp lockdown there was a recovery, but activity has been trundling along at a significantly lower level than usual for months:  Very similar trends are visible in the main European economies, which had a stricter initial lockdown, and appeared for a while to have enjoyed a clearer victory over the virus. All are now stuck in neutral at a level of activity significantly below normal. The number of people working at their official workplace remains well below normal, particularly in the U.K.:  Amid such conditions, and with authorities in disarray over how to deal with the pandemic, how can stock markets remain so close to all-time highs? In brief: - There is hope that a fiscal stimulus will be along shortly, as a result of Democratic victories in the U.S. elections (even though betting markets are moving to give Trump a better chance of holding on to power);

- Central banks are still largely trusted to keep the lid on interest rates at historically low levels — which effectively leaves investors with little choice but to buy stocks rather than bonds; and

- A vaccine should be along shortly (or possibly not).

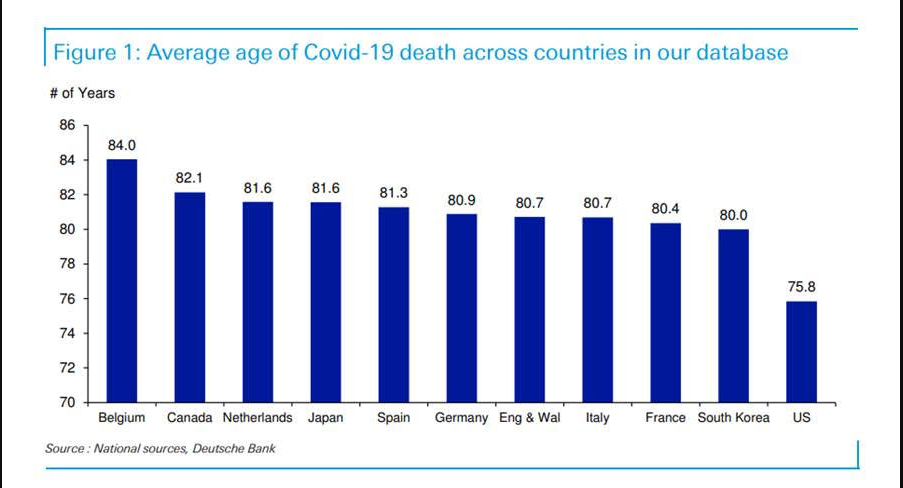

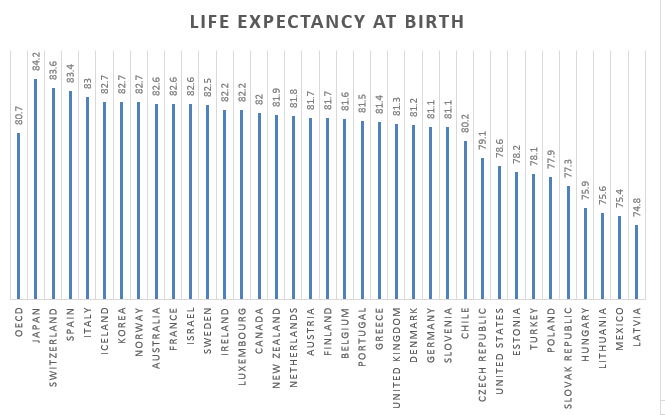

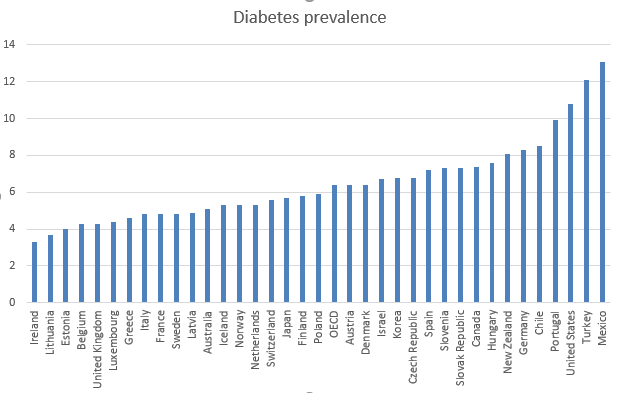

Whether this is masterly tuning out of political noise, or dangerous obliviousness to elevated risks is a matter of taste. Covid, Longevity and Globesity It is well known now that Covid-19 usually kills only the very old. But it is startling how much this varies from country to country. The following chart is from the inestimable Jim Reid at Deutsche Bank AG:  The U.S. is a remarkable outlier. How can that possibly be? One explanation , which feeds into the political debate of the moment, is that all the other developed countries on this chart have some form of universal state-provided healthcare. But rather than get embroiled in that debate, let's look at the normal average age of people when they die. The following is a chart of life expectancy (in years) at birth for all the members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which I put together on Excel (sorry for the crude graphics):  The U.S. has lower life expectancy than the Czech Republic or Chile, and is lagged only by countries that are significantly poorer. It trails the other major economies by several years, in many cases roughly equal to the gap in the age at which Covid-19 victims die. It might make sense for the U.S. healthcare debate to revolve around treating this as a national disgrace and trying to make common cause over fixing it, rather than having an arid political argument, but I digress. The serious American problem with obesity is well known. One of its greatest life-shortening effects is diabetes. Here are the most recent OECD numbers on diabetes prevalence:  In this baleful category, the U.S. lags behind only the much poorer nations of Turkey and Mexico; it has more than double the diabetes prevalence of the main developed economies of Europe. Once the country has finished tearing itself apart over the pandemic, which will probably only happen once the virus has finally gone away, a new debate over diabetes and obesity will be necessary. Let's hope it can be more constructive than the current one. For now, the numbers shed light on why the U.S. has had a relatively difficult time containing the pandemic, and also suggests that a "Swedish" model of "focused protection" for those most vulnerable could be harder to apply to the U.S., because a far higher proportion of Americans are at risk. Allowing most of the population to return to life as normal is going to require confining a lot of people to their homes for the duration — judging by the diabetes numbers, maybe twice as many as in Sweden, as a proportion of the population. That isn't feasible. Concern about the obesity epidemic, and not just in the U.S., is nothing new. Neither is the attempt by investors to profit from it. Digging into my cuttings files I found that BofA Securities Inc. published a huge report on "Globesity" back in the summer of 2012, which it described as one of three global mega-trends. It offered a list of 50 stocks that it thought would benefit from a global fight on obesity, including some counterintuitive names such as Pepsico Inc. and Nestle SA, both of which it thought were better positioned to move toward less fattening products — but which produce plenty of products, such as sugary drinks, that contribute to obesity. A year earlier, Solactive AG started an obesity index of smaller companies working in drugs and diagnostics connected to the issue — primarily diabetes. In due course, Janus Henderson launched an exchange-traded fund to track it, with the brilliant ticker symbol "SLIM." In January of this year, the announcement was made that the ETF would be liquidated, an event that finally took place on March 12. That represented a missed opportunity. This is how the obesity index has performed relative to the S&P 500 since inception:  The SLIMmers have done even better than the FANGs since the market bottom. Sadly, the ETF had been wound up the week before. Judging by the valuations of the obesity index at present, the short-term opportunity may have passed. It trades at a price-earnings ratio of 94.66, which is reduced to 30.4 if only those companies that are currently making a profit are included. For the longer term, however, the lesson that all countries should learn from the dreadful experience of the U.S. over the last eight months is that any given health emergency grows that much worse if you are overweight. It's too late to help in the battle against Covid-19, and it's too late to profit from the smallest companies working in the fight against diabetes, but the world will have to combat obesity. In due course, capital will flow toward financing that fight. Survival Tips It is approaching eight months since I last attended a conference and met people. Such events are a staple of how journalists get their information, and how we all make new contacts (and occasionally even friends) that help us in life and business. Zoom meetings just aren't the same. For those of us who work for organizations that make money from putting on conferences, it hurts financially, too. So here is a tip for any of you wishing you could jet off somewhere to spend a few days in a subterranean windowless hotel ballroom with a lanyard around your neck: Try reading this great piece from 2017, written by Kip McDaniel, now the editor-in-chief of Institutional Investor, on "the worst investment conference imaginable." Conferences are often toe-curlingly, teeth-grittingly awful. Among his highlights: 11:30 a.m.–1:00 p.m.: A Random Series of Extremely Specific Thoughts on Emerging Markets. Ninety minutes required to get through 108 slides. Audiovisual equipment will break midway through, prompting panel to run over by ten minutes. "I'll just speed through the regional election in Laos . . . and finish with a deep dive into how agrarian reforms have been impacting Guyanese peanut production." After I shared it on Twitter, my followers helpfully corrected some omissions. For example, no investment conference is complete without someone who shows up in leathers and argues vociferously for bitcoin and cryptocurrencies. And then of course this gathering needs to add a two-hour session, starting at 3:00p.m., on the regulatory environment and compliance. But if you read this piece, yet another day sitting in your spare room "talking" to people on Zoom will begin to seem so much better. Anything beats being buttonholed by the very person you were hoping to avoid while you wait impatiently for someone to refill the coffee carafe. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment