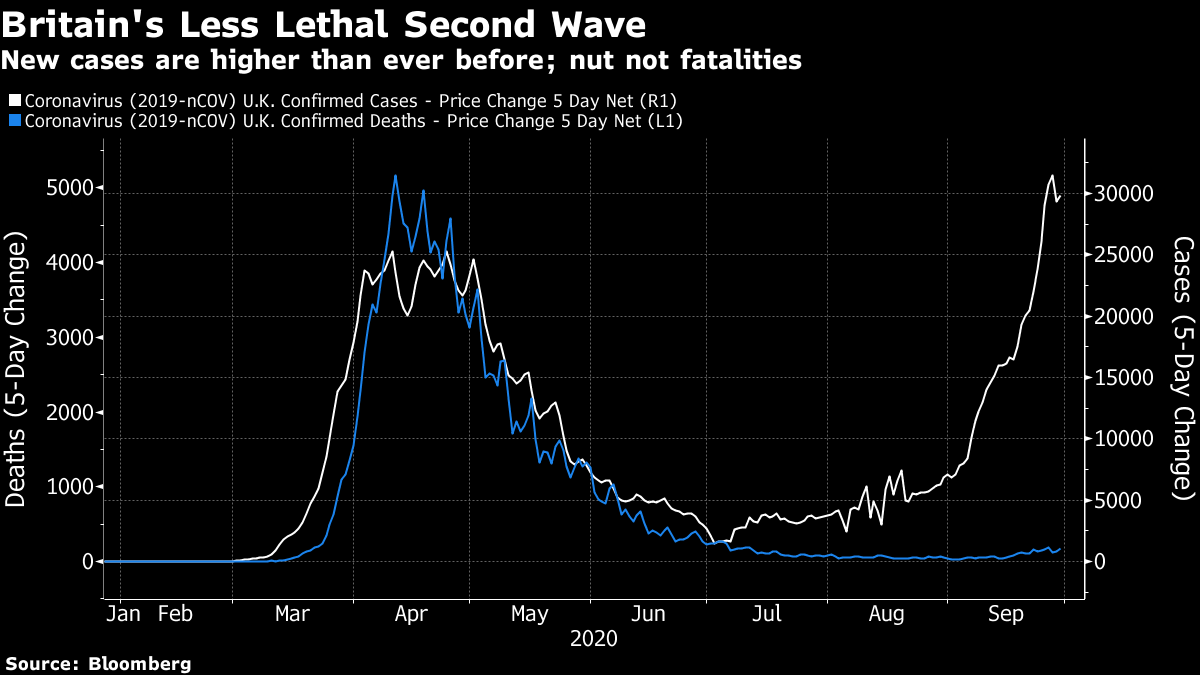

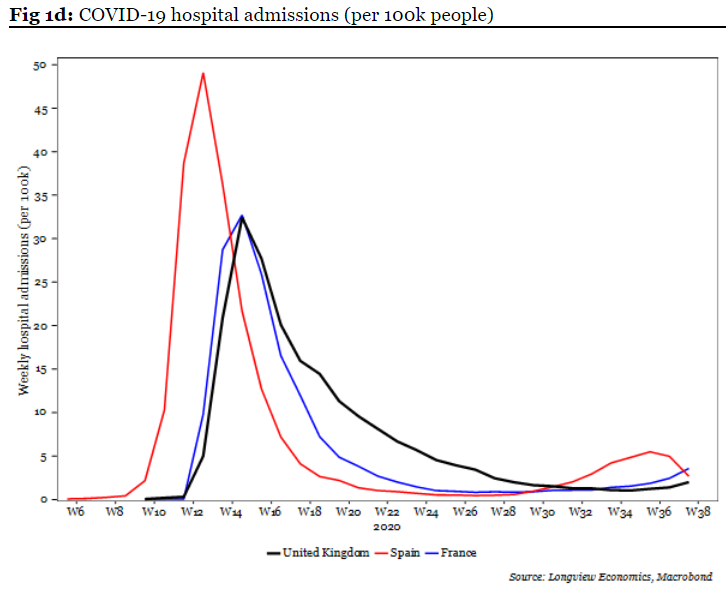

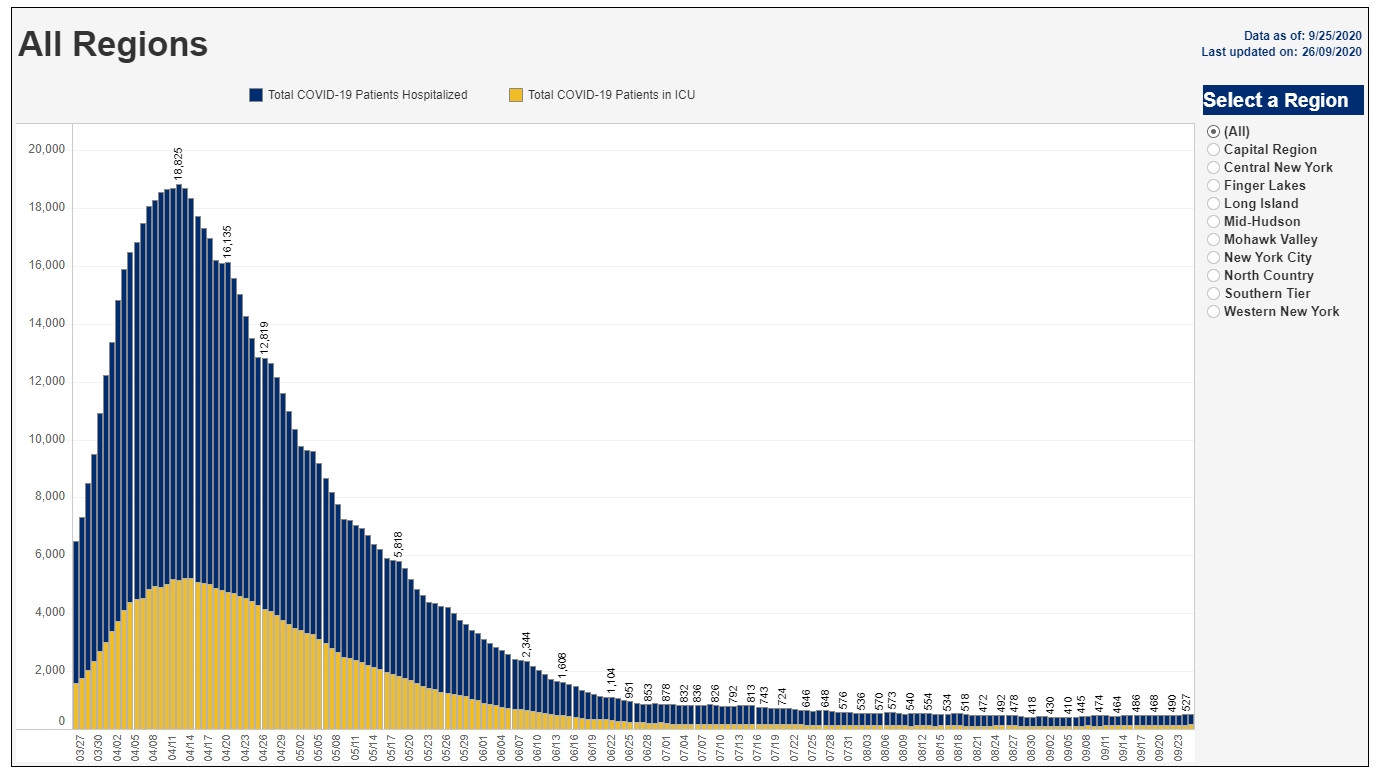

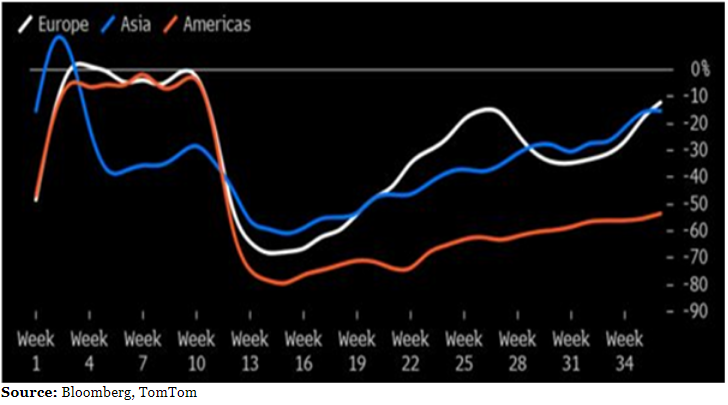

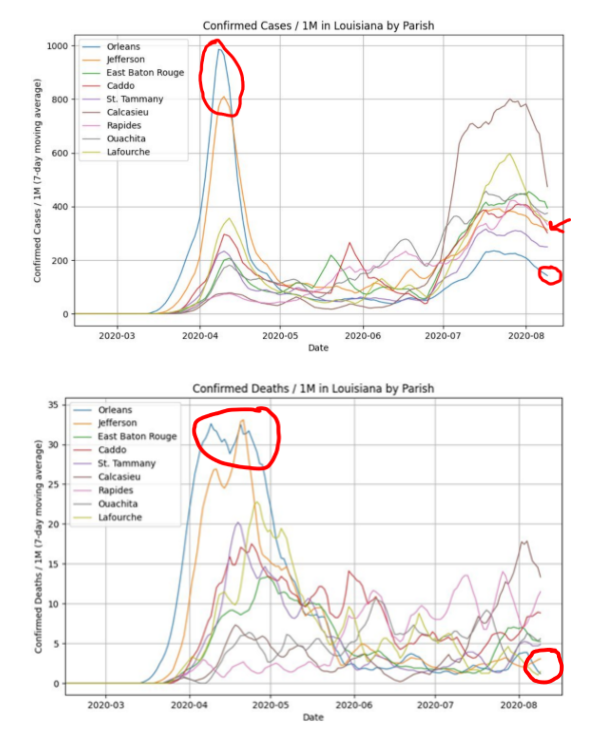

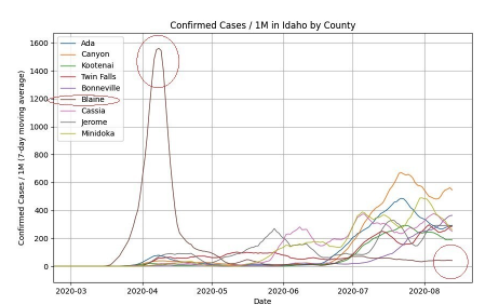

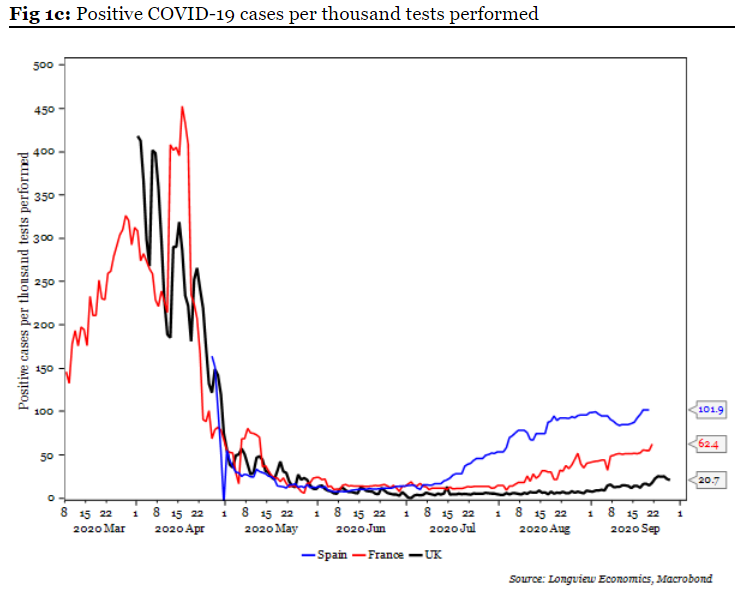

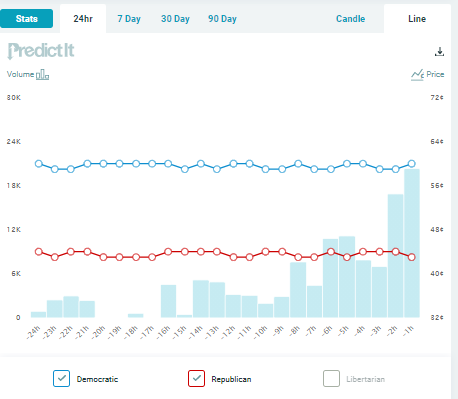

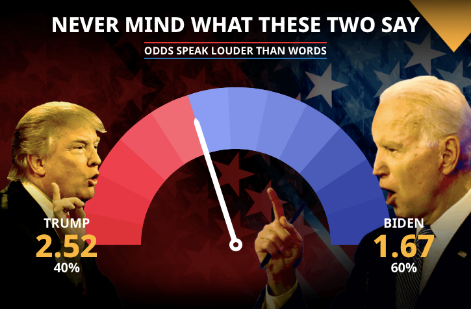

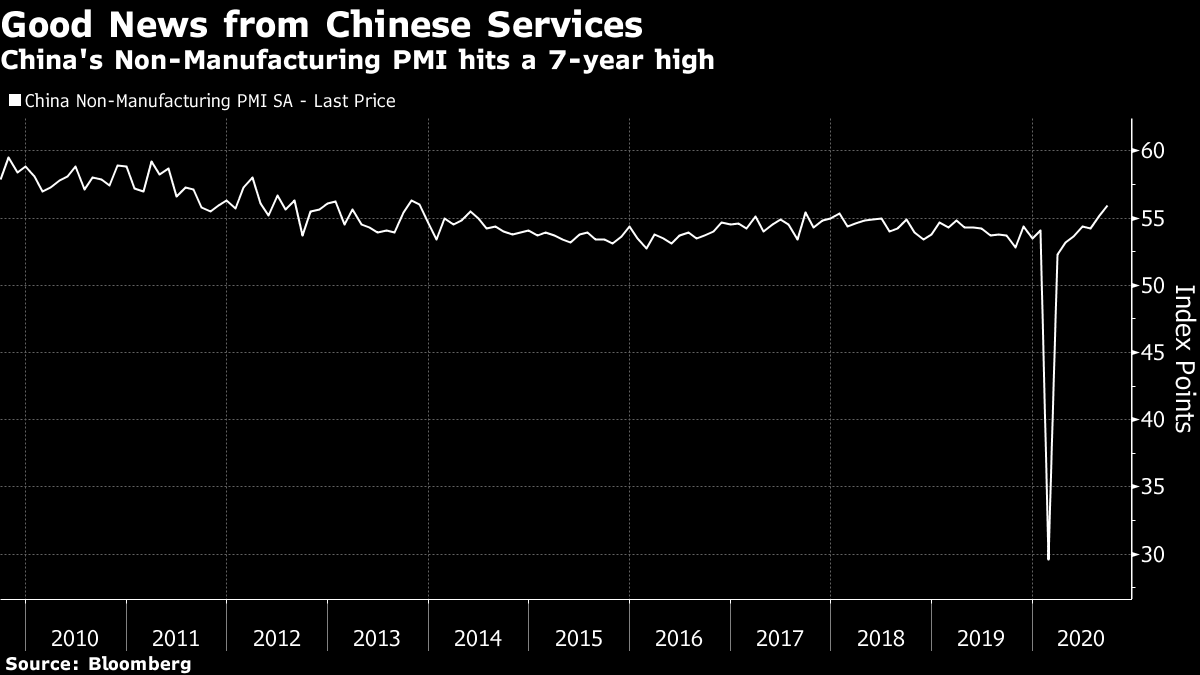

Herd MentalityIs there a deeper wave than this? Britain is once again tearing itself apart over how to respond to Covid-19, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson facing an insurrection from his own MPs over plans for sweeping second lockdowns to combat the coronavirus. Worries about an uptick in cases in the U.S. have contributed to the market turbulence over the last few weeks. Why then are the markets managing to maintain their relative calm? Obviously, central banks have much to do with this. But critically, it is still reasonable to hope that there won't be a true "second wave." Scientists are divided on the issue, and even the most alarming data of the last few weeks don't establish that one is under way. To start with the U.K., where the politics are currently most intense, the latest data show new cases running at a higher level than they did during the first wave in the spring:  The critical ground for hope is that deaths are far lower, and have barely risen as yet. Death is a lagging indicator (to use cold but accurate language), so it is helpful instead to look at hospitalizations, as charted here by Longview Economics:  The U.K. and France suffered comparable first waves, and are both seeing negligible second waves, as measured by people admitted to hospital. Spain suffered more grievously in the first wave, and had a greater but still relatively muted second wave, at least when measured this way. This follows a familiar pattern from other places that have already suffered one major outbreak. This is New York State's history of hospitalizations so far this year. The disease hasn't been extinguished completely, but it seems to be firmly under control:  Meanwhile, if we want to know about the impact that the disease is having on behavior, it makes sense to look at numbers for traffic congestion. The following chart, also from Longview Economics, shows congestion as a percentage of the figure for the same week last year for Europe, the Americas and Asia.  In Europe and Asia, mobility is still down noticeably enough to have some effect on the economy, but there has been no sign of people cutting back on travel in recent weeks. The first wave showed that people tended to do this voluntarily, without needing to be prompted by the government, if they were in the middle of a serious outbreak. This suggests there is little sense of a second wave on the ground as yet. All of this is circumstantial evidence that "herd immunity" is closer than many had predicted. For two cases, Adam Patinkin of David Capital Partners LLC in Chicago points to a fascinating if inadvertent controlled experiment. During the first wave in the spring, the U.S. Deep South was largely spared. The only city to suffer a serious outbreak was New Orleans, which went ahead with its huge annual Mardi Gras festival. The rest of Louisiana was relatively unaffected Once the second wave hit, however, it was the reverse. New Orleans saw only a minor tick up in infections, and was the state's least-affected parish. This at least gives some circumstantial support to the notion that the initial outbreak helped the city develop enough herd immunity to avoid a second wave.  Another interesting test case is the very different and dispersed state of Idaho. The county of the Sun Valley ski resort kept accepting tourists into late March. It's easy to identify it on the following chart — and also to see that it went on to be by far the least affected county when the rest of the state suffered its first wave later in the summer:  Is it just wishful thinking that the virus will go away? There may be an element of this, but there is more to it than that. A big and growing literature is providing support to the idea that the threshold for achieving herd immunity is lower than previously thought, and proponents include senior epidemiologists at universities like Harvard and Oxford. The theoretical basis for hope lies in heterogeneity. Not all people will be equally susceptible to the virus, and there is now a debate over why some are so much worse affected than others. Whether prior exposure, possibly to other coronaviruses, could help some people to resist Covid-19 is now the subject ofintense research. Similarly, not all people will be equally exposed. Some naturally come into contact with far more people than others do, during the course of their daily lives. These people are more likely to have had it already, and won't therefore infect anyone else in a second wave. This paper by Patinkin of David Capital explains the argument clearly. The mathematics are head-spinning. Gabriela Gomes of the University of Strathclyde in Scotland, one of the most respected mathematicians in the field, explains the ideas behind heterogeneity and its lowering of the threshold for herd immunity in this podcast. You can also see her discussing her models and how their predictions are working out as part of a video presentation for Boston University here. What she does make clear is that the second wave of cases in Britain and particularly Spain has been significantly higher than her models predicted earlier in the year. This needs to be explained. As Bloomberg Opinion columnist Tyler Cowen points out in this blog post for Marginal Revolution, the herd immunity theory is about fewer people being infected, not about fewer people dying (which might be achieved by improved treatment as medics learn to deal with the disease). The most plausible explanation advanced to date is that the Covid-19 testing currently under way is too sensitive and picks up insignificant quantities of virus, in some cases dead virus from a previous infection. As Gomes pointed out in her presentation, testing in both Britain and Spain has moved forward at a much faster rate than she and her colleagues had predicted. The rate of positive tests remains very low, particularly in the U.K., as this Longview Economics chart illustrates:  Is Britain's second wave a quirk of conducting many more tests with over-sensitive parameters? Working that one out will require some very detailed science. It's far too soon to say that the case for herd immunity having arrived already has been proved. A second major outbreak in a place that has already had one would do fatal damage to the theory. But every scientific development is eagerly gobbled up by the investment community. If you want an explanation for why the second wave is being received so much more calmly than the first, these ideas have much to do with it. Debate Night in AmericaIt was a distasteful spectacle, and at the end of the first presidential debate all of us were 90 minutes older than when it began. Other than that, it appears to have changed little. Because time is beginning to run out and the polls say that Joe Biden had his nose in front entering the debate, that means the former vice president is regarded by betting and prediction markets as a slight winner. This is trading over the last 24 hours in the Predictit market, on the contract predicting which party wins the election. Volume was heavy during the debate, and it translated into a just-perceptible improvement for the Democrats, nothing more:  Bookies reported much the same thing; betting markets had been slightly more optimistic for Donald Trump than the prediction markets, but now they are in exact alignment. Like Predictit, the Betfair exchange now puts Biden's victory chance at 60%:  Before the debate, Biden's odds were 4/5 on (56%). They are now 4/6 (60%). Trump's odds, if you fancy a bet, widened from 11/8 to 6/4. Biden is ahead but not by the kind of margin that anyone would want to risk a lot of money on. All of this broadly makes sense. Biden "won" by surviving the debate and giving the president one less opportunity to bring him down in future. Both did make a few statements that might be usable against them (Biden didn't rule out packing the court and Trump didn't condemn white supremacy), but it was hard to hear what either of them were saying for lengthy tracts of the debate. It's hard to see how any genuinely undecided voter would have changed their mind on the basis of this. It was an embarrassing display, far removed from the Lincoln-Douglas debates or Prime Minister's Question Time in the U.K. But did it affect any markets that matter, with money at stake? Not really. Nothing out of the usual happened during the debate in those that were open and would be most directly affected by U.S. politics. There was quite a dip in S&P 500 futures, but after the debate was over. As far as the markets were concerned, the China non-manufacturing PMI data were much more important. Services have been lagging somewhat in the recovery so far, as China has had to postpone its transition to a consumer-led economy — so the best services PMI number in seven years seems to have cheered up those in the Asia-Pacific. It certainly makes for a spectacular chart:  Maybe I should have spent this evening researching China rather than wasting 90 minutes of my life watching the debate. Lesson learned. Survival TipsDon't watch the next presidential debate. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment