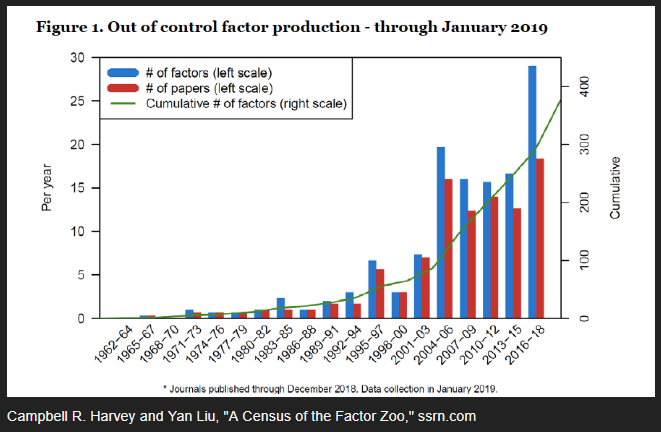

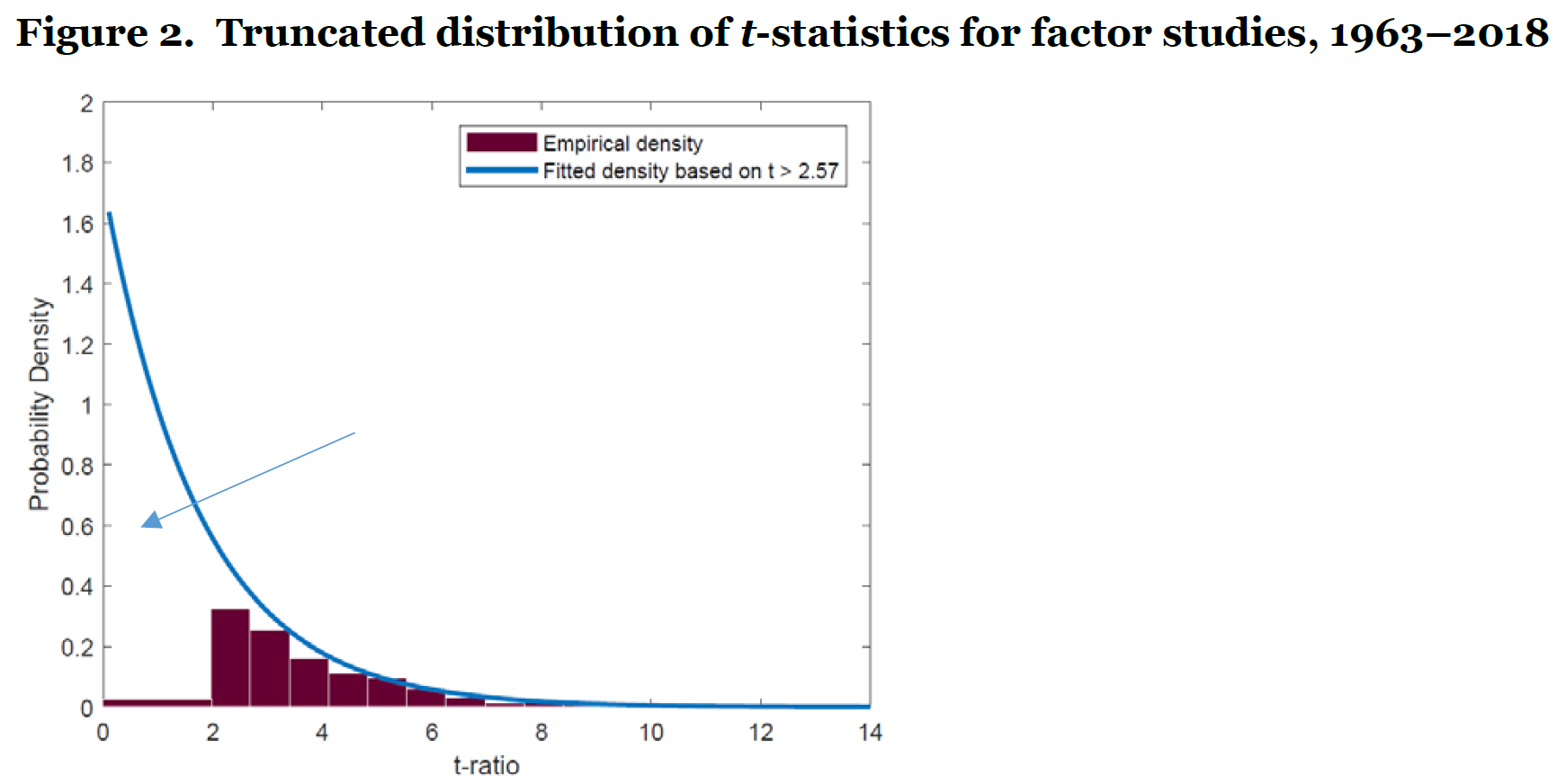

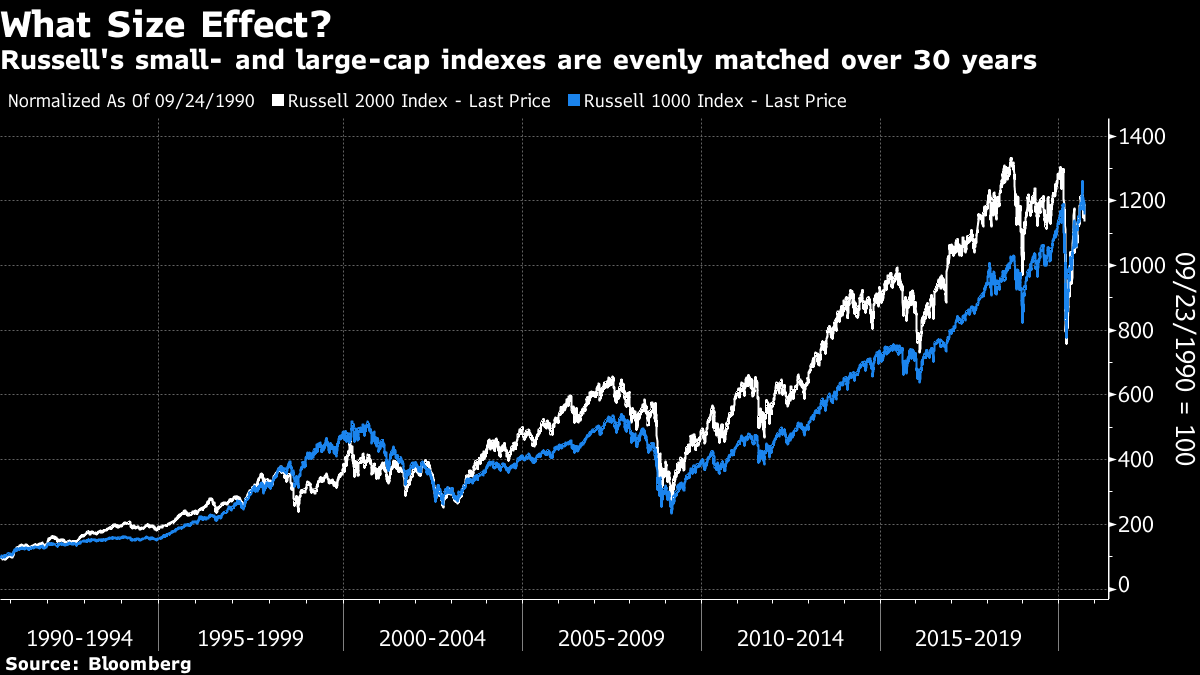

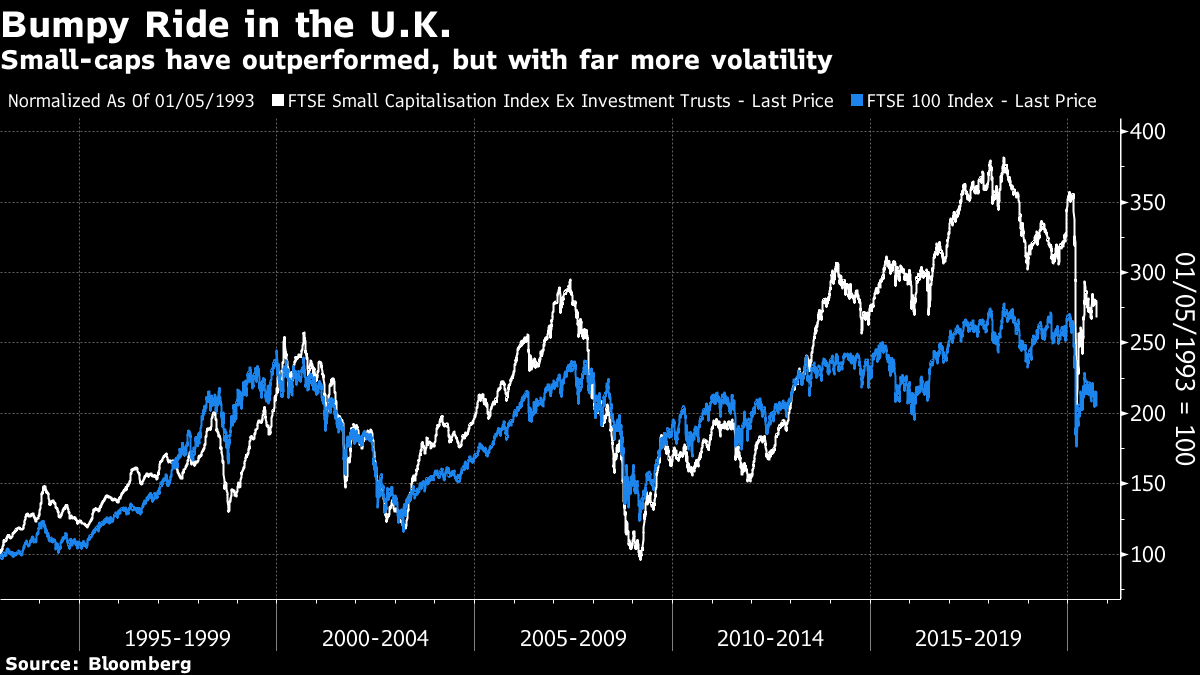

Size Isn't EverythingThe academic hunt for investment factors, which can predict that certain stocks will tend to outperform in the long run, has turned into something of an arms race. A generation ago, academics identified three factors that more or less everyone agreed worked to some extent — momentum (winners keep winning while losers keep losing); value (cheap stocks beat expensive ones); and size (small companies tend to beat bigger ones). There was a long and turgid debate over whether these factors could really all be explained in terms of risk, which would need to be rewarded in the long run, or whether they showed persistent irrationalities or anomalies in the market. Things have moved on. Academics now claim to have identified more than 400 factors (which makes it a wonder that anyone ever failed to beat the market). Meanwhile, doubts over the "small is beautiful" theory have reached such a point that many question whether it exists at all. The finding on the ludicrous number of factors comes from A Census of the Factor Zoo by Campbell Harvey and Yan Liu. With the huge commercial success of "smart beta," or passive funds aiming to reduce costs while following a systematic factor strategy, it is no surprise that young academics think that they can build a reputation for themselves by unearthing a new factor:  Generally, a lot of factors tend to stop working once they have been identified in the literature, suggesting either that investors immediately move to take advantage of the anomaly, and thereby end it, or that the definition had been made far too specific and complicated in a bid to make its back-tested results look better. It is notable that when academics do the work and find that the factor they were exploring does not, after all, beat the market, they tend not to add to the sum of human knowledge by publishing their work. This may well mean that many waste time looking in the same place. To demonstrate this, Harvey and Liu offer this chart. The horizontal axis shows the t-statistic, the standard measure of how statistically robust a finding is. The number of factors published with only low statistical robustness (meaning researchers had done the work but discovered there wasn't a strong investment factor to be found) is minimal. In the following chart, the columns on the left should be the tallest. That they are not suggests that they have been thrown into the filing cabinet — and also that academics have tried to identify many thousands of persistent market anomalies:  Those interested in the full list of factors, many of which get very abstruse, can find Harvey and Liu's updatable online spreadsheet here. While young academics are trying to add new factors, grizzled veterans are concluding that the small-company effect does not, after all, exist. Over the last few decades, there is little clear small-company dominance. The outperformance of the FANG stocks in recent years has helped this. Small-caps have had their noses in front much of the time, but at the level of the Russell indexes, the most widely used benchmarks of market-cap effects used by the industry, the factor is muted at best. Smaller companies tend to do a little better during good times, only to give back all of their advantage in market breaks:  Repeating the same exercise for the U.K., leadership between small- and large-caps seems to alternate with nothing that looks like a consistent factor. Smaller companies have led in recent years, largely because the biggest British companies tend to be in unpopular sectors such as energy, materials and banking:  That is what we can tell from eyeballing the simplest charts. And far more sophisticated statistical work confirms it. Small-caps tend to do relatively well when the market is doing well, and badly when the market is down — which is another way of saying they have high sensitivity. This is one of the most profound factors, know in the business as beta. If small companies tend to have a high beta, and all their outperformance can be attributed to beta, then there is no specific small-company effect. That is exactly the finding by Cliff Asness, who heads the AQR fund management group, and in earlier days studied for his doctorate under Gene Fama at the University of Chicago, the Nobel prize-winner who promulgated the efficient markets hypothesis, and who later with Kenneth French identified the size, value and momentum effects. Back in the early 1980s, Asness says in a new paper called There Is No Size Effect, there was indeed a meaningful effect at work. That has changed: The original work on the size effect back in the early 1980s didn't miss this, finding that small beats large by more than market beta could explain. But, the near 40 years since those findings have not been kind – both in realized returns and in re-examination of the original finding. A series of cumulative challenges, many of which we have summarized …, all have reduced the historic "net of market beta" return to small vs. large, ultimately leaving nothing.

Asness and team have now revisited the data, brought it up to date, and broken it down to daily returns. The regressions are all in Asness's piece, and best not listed here. The bottom line is emphatic. In effect, Asness's team found that even a few decades ago, the apparent outperformance of small companies over and above their beta was only because their beta had been underestimated, due to their illiquidity. Often, thanks to the difficulty trading, they don't show their full market reaction straight away, but only with a lag, once traders have been able to make a trade. Accounting for this lag and recalculating the beta means, to quote Asness's typically pungent language, that "you really don't find any size effect. Zippo. Nada." It's not that the small-company effect has steadily disappeared. It was never there. If you think the market is going up, it still makes sense to ride high-beta stocks while it is rising, and that will mean picking a lot of small stocks. But there is no point in specifically buying small-caps as an asset class. Small-caps tend to be under-researched, meaning they can often yield seriously mis-valued stocks. It makes sense for value managers to search among small companies. But you are just as likely to find overvalued as undervalued stocks. You still need to be good at spotting value. Meanwhile, another paper by David Blitz and Matthias Hanauer of Robeco Quantitative Investments, called Settling the Size Matter, nearly resurrects a narrower version of the small-company effect, before finding that it is close to impossible to exploit. (Asness, inimitably, suggests that the paper's title is a little misleading and proposes this alternative: "A Short Note on the Major Enhancements to Our Understanding of Size from the Two AQR Papers We Recapitulate but with Some Quibbles About International Results and Adding a Further Study of Implementability." He does also concede that it's a good paper.) After some exhaustive research, the Robeco paper finds that the small-cap factor does deliver some performance, but only when linked to "quality" — which has various descriptions in the literature, but generally means that a company has a strong balance sheet along with reliable profits. But on closer examination, they found that it wasn't so much that high-quality small companies would do well. Rather, really terrible small companies with weak balance sheets were a great bet to sell short. This isn't a surprising finding, though it does confirm that for those prepared to do a lot of crunching through balance sheets and make themselves unpopular, shorting small-caps could be profitable. This is their summary: the regression results do imply that size adds significant value when used in conjunction with quality. Taking a closer look at this result, we find that it is entirely driven by the short side of quality portfolios and breaks down for the long side. In sum, the added value of size appears to be limited to investors who short US junk stocks.

None of this means that you shouldn't invest in smaller companies. But you shouldn't, alas, expect them to do well just because they're small. Size isn't everything. Survival TipsI have a favor as well as a tip. I am working on a fresh essay about the moral dilemmas raised by the coronavirus. This time, the question is whether it is acceptable to pursue a strategy of achieving herd immunity (i.e. by knowingly accepting infections to speed the time when the disease runs out of fresh bodies to prey on). With a second lockdown beginning in the U.K., President Trump raising the concept directly, and plenty of research pinging between investors to suggest that herd immunity may be close, it becomes an urgent issue. Whatever the science tells us, it cannot on its own resolve the question of how to proceed. Once we have some guidance on what the outcome of a strategy will be, there is a still moral judgment to be made. I'd be very interested to hear from anyone with views, particularly those with useful research to contribute. After six months of lockdown, for more or less everyone, and the loss of loved ones for many, feelings run high on this subject. It's much less stressful to cover quants trying to measure the small-company effect. So it is time for a few more "panic button" pieces of music. Let's go with the solo piano. Bach's Goldberg Variations, as played famously by Glenn Gould, are strangely hypnotic. They never grow old. And then maybe try some of Chopin's preludes: in particular there is the deceptively simple but beautiful 4th prelude (played by Khatia Buniatishvili), the famous "Raindrop" or 15th prelude (played by Lang Lang) and the resounding chords of the 20th prelude (played by Grigory Sokolov). The 20th prelude really didn't deserve to get turned into a song for Barry Manilow and Take That. |

Post a Comment