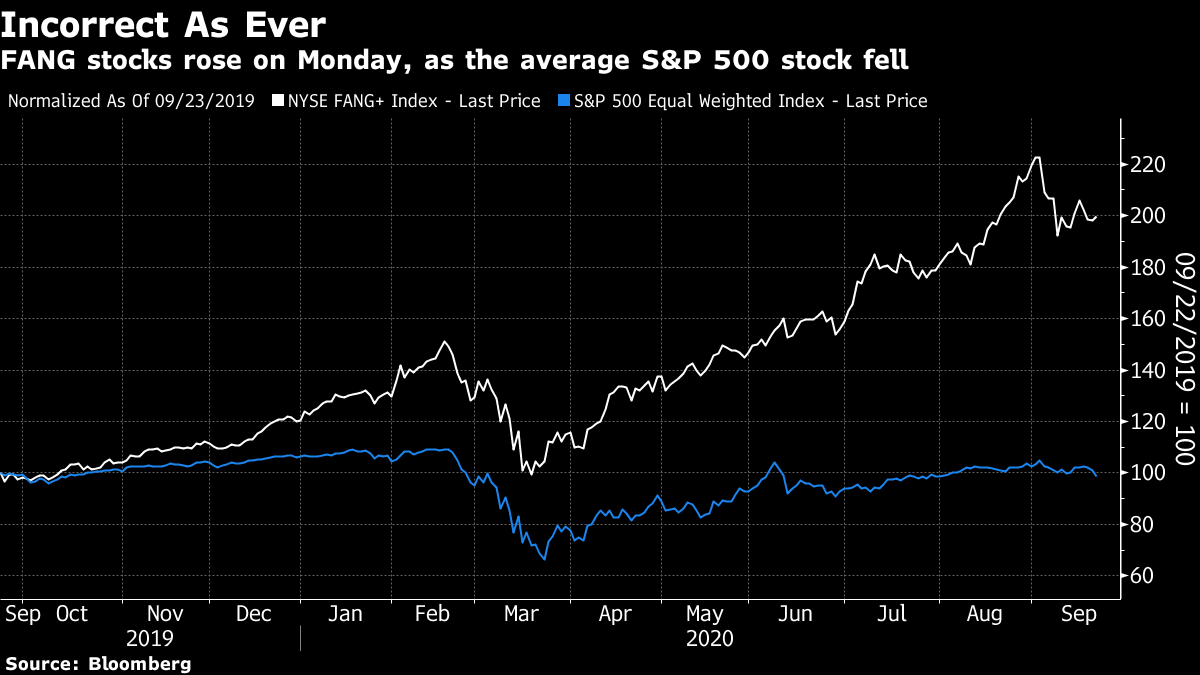

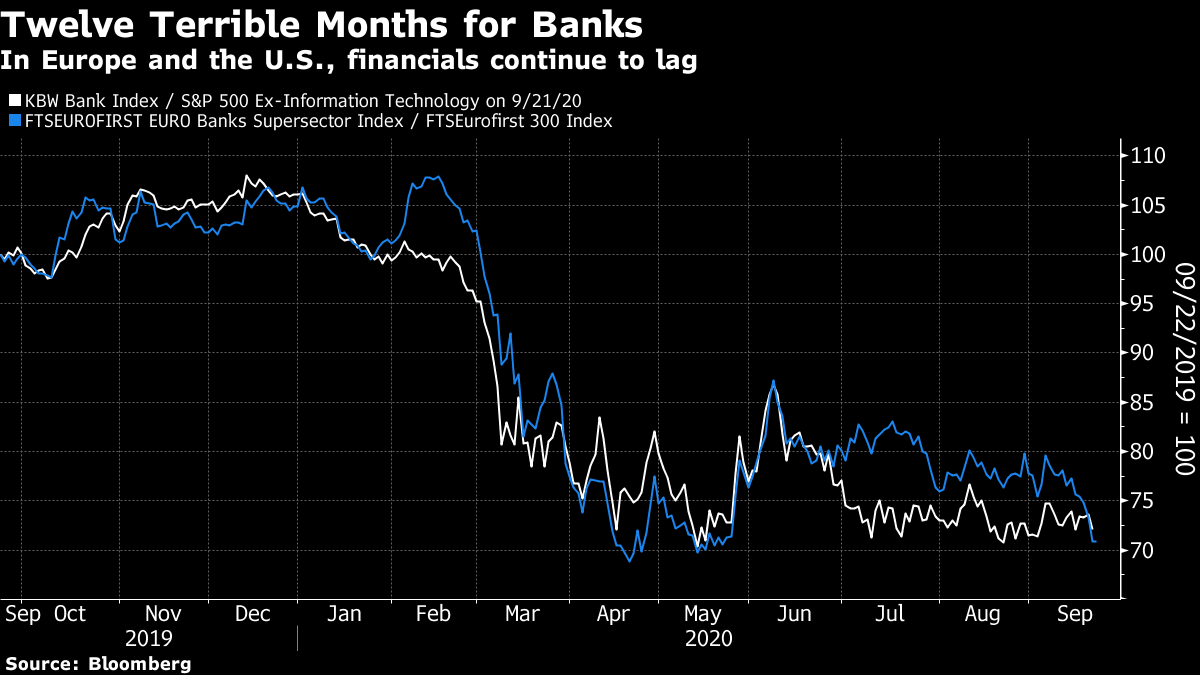

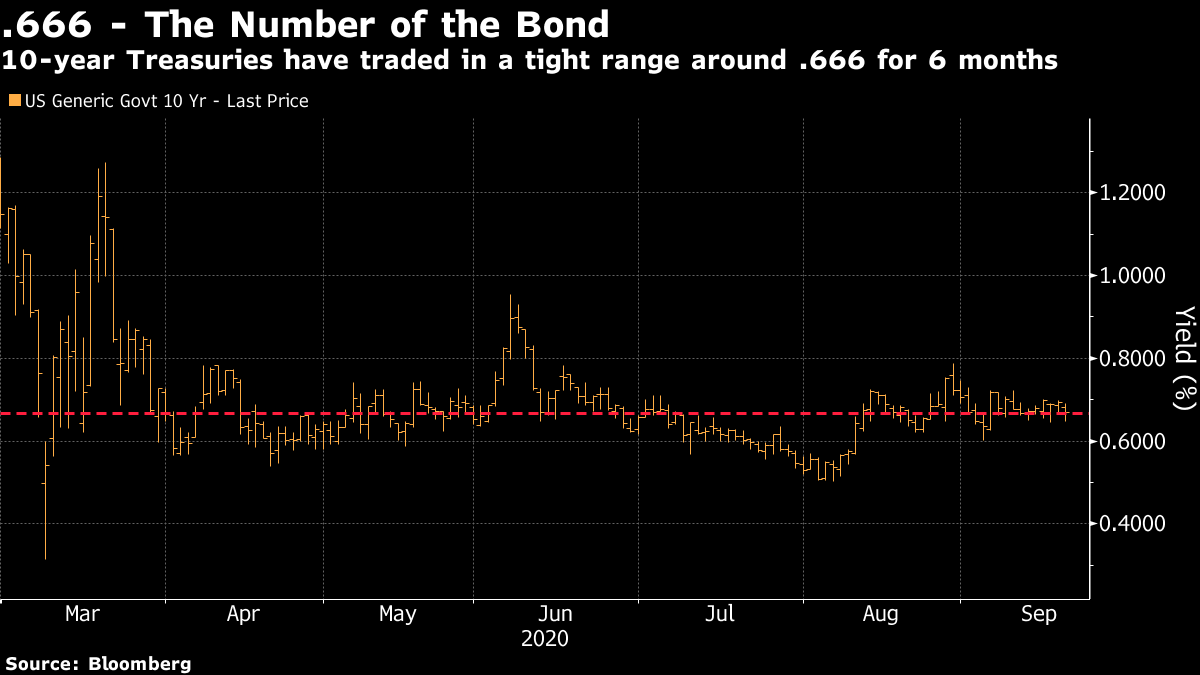

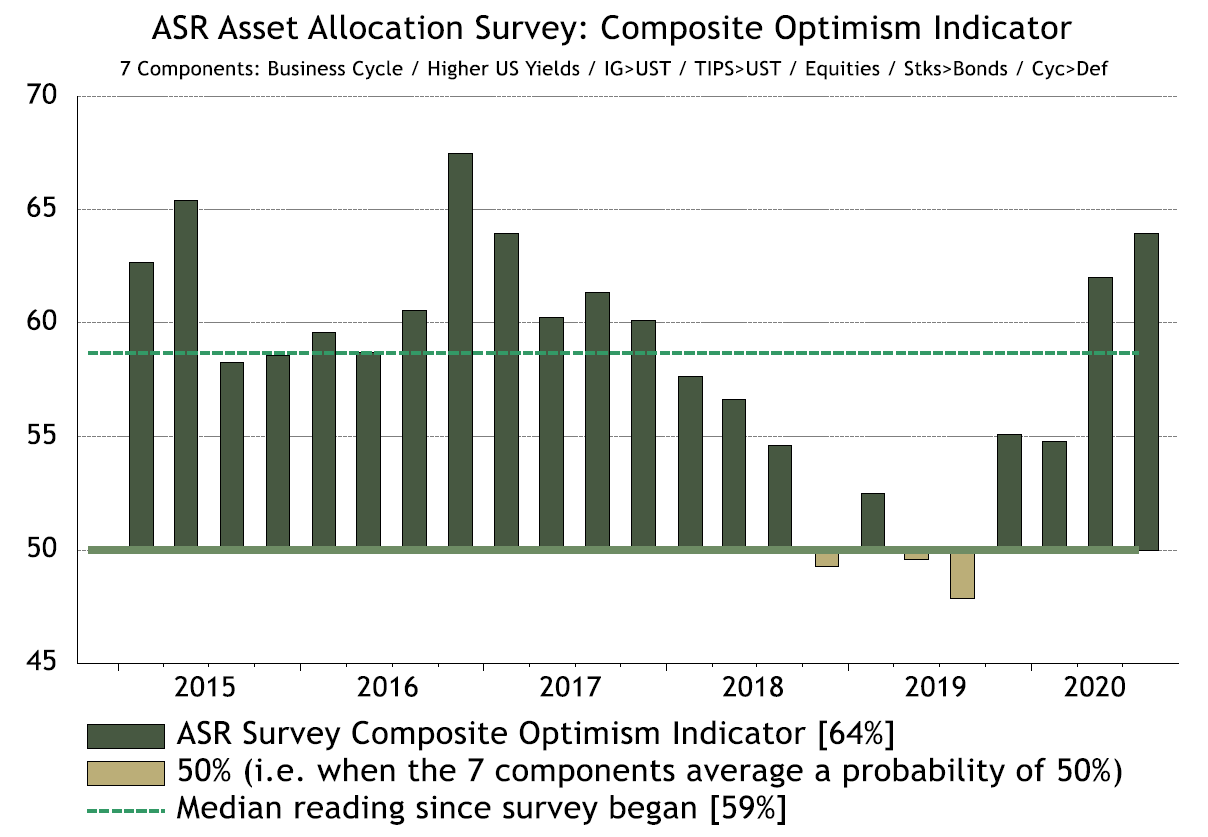

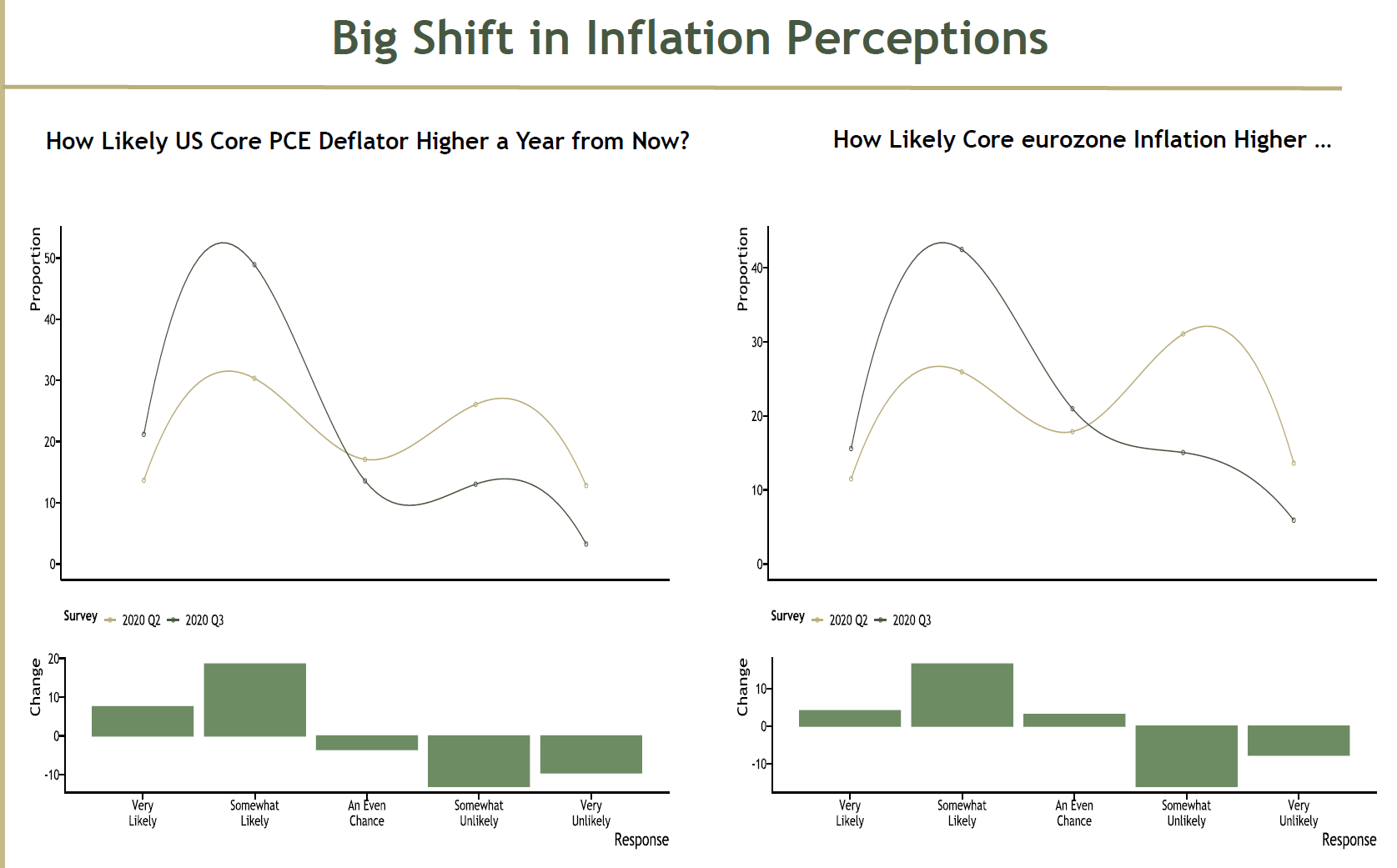

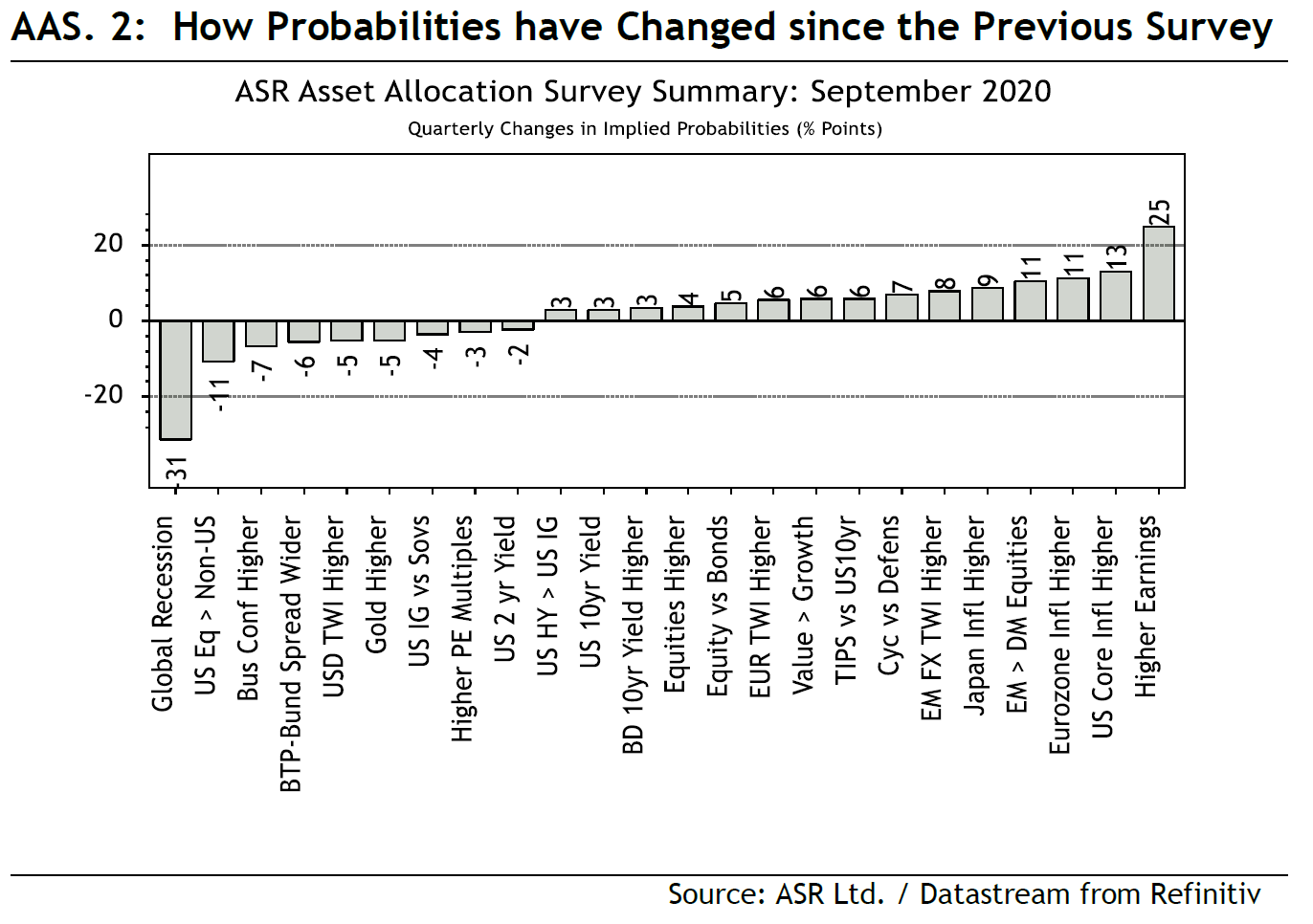

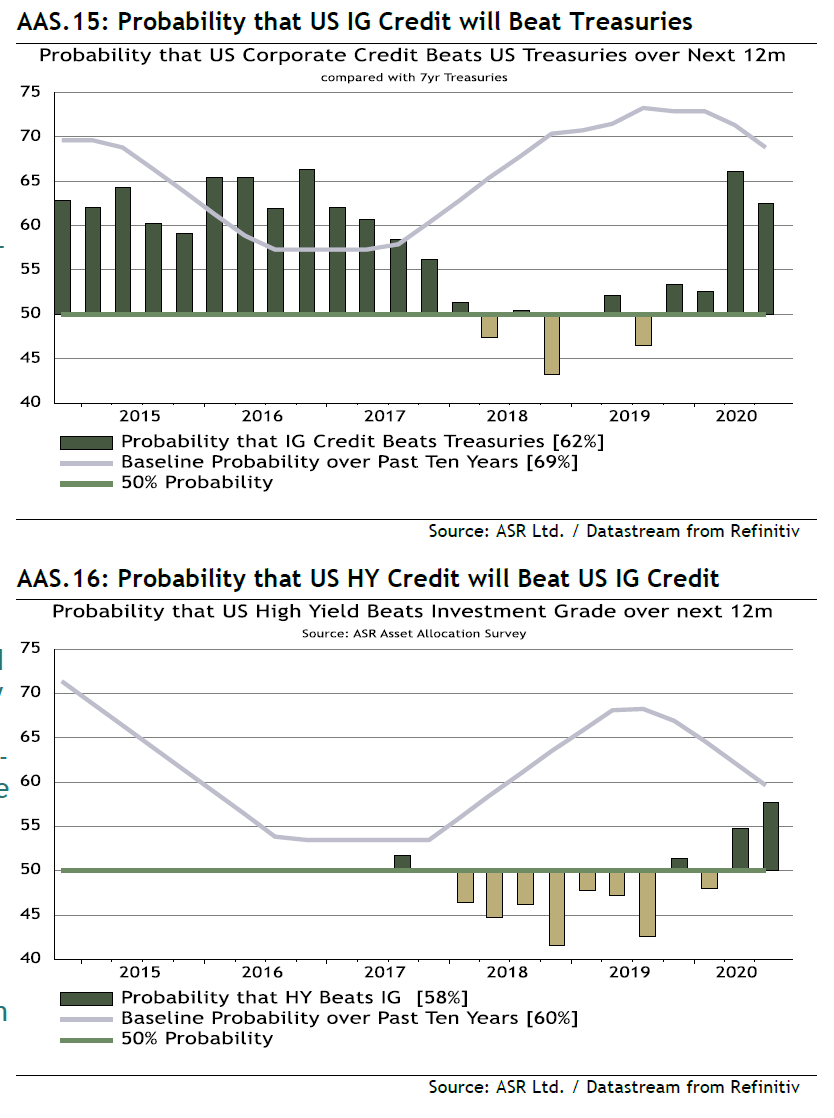

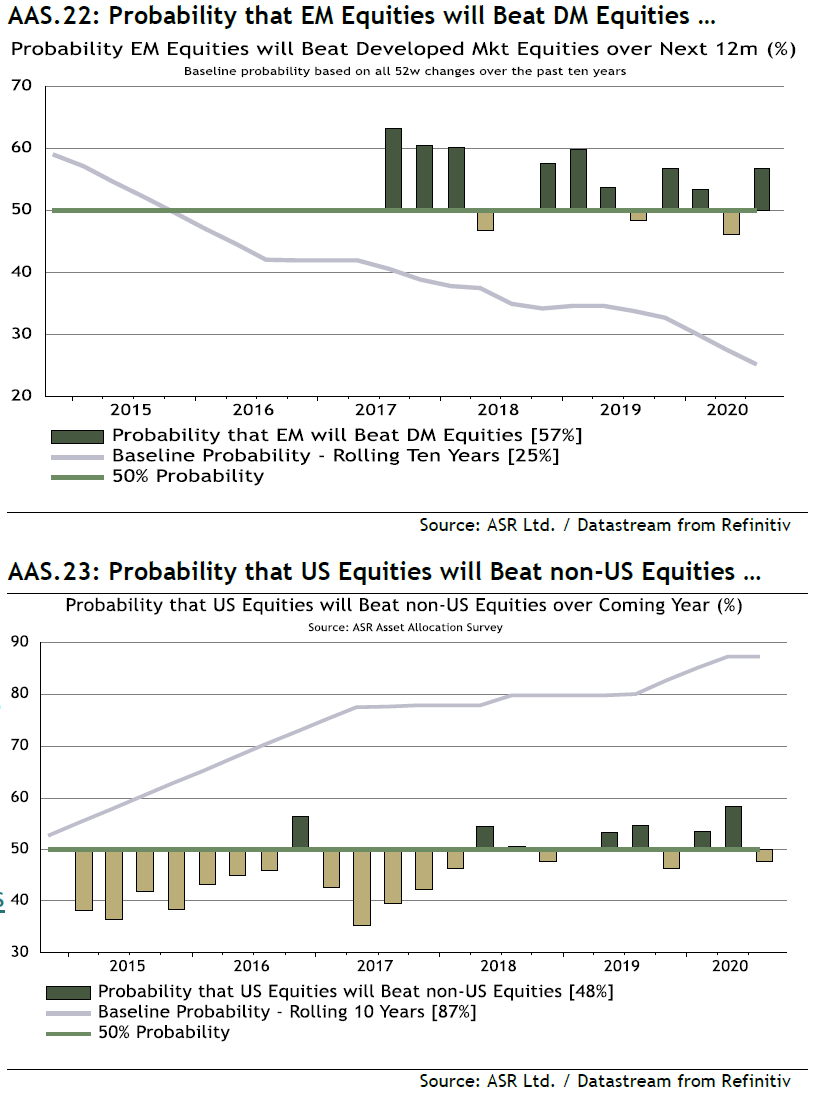

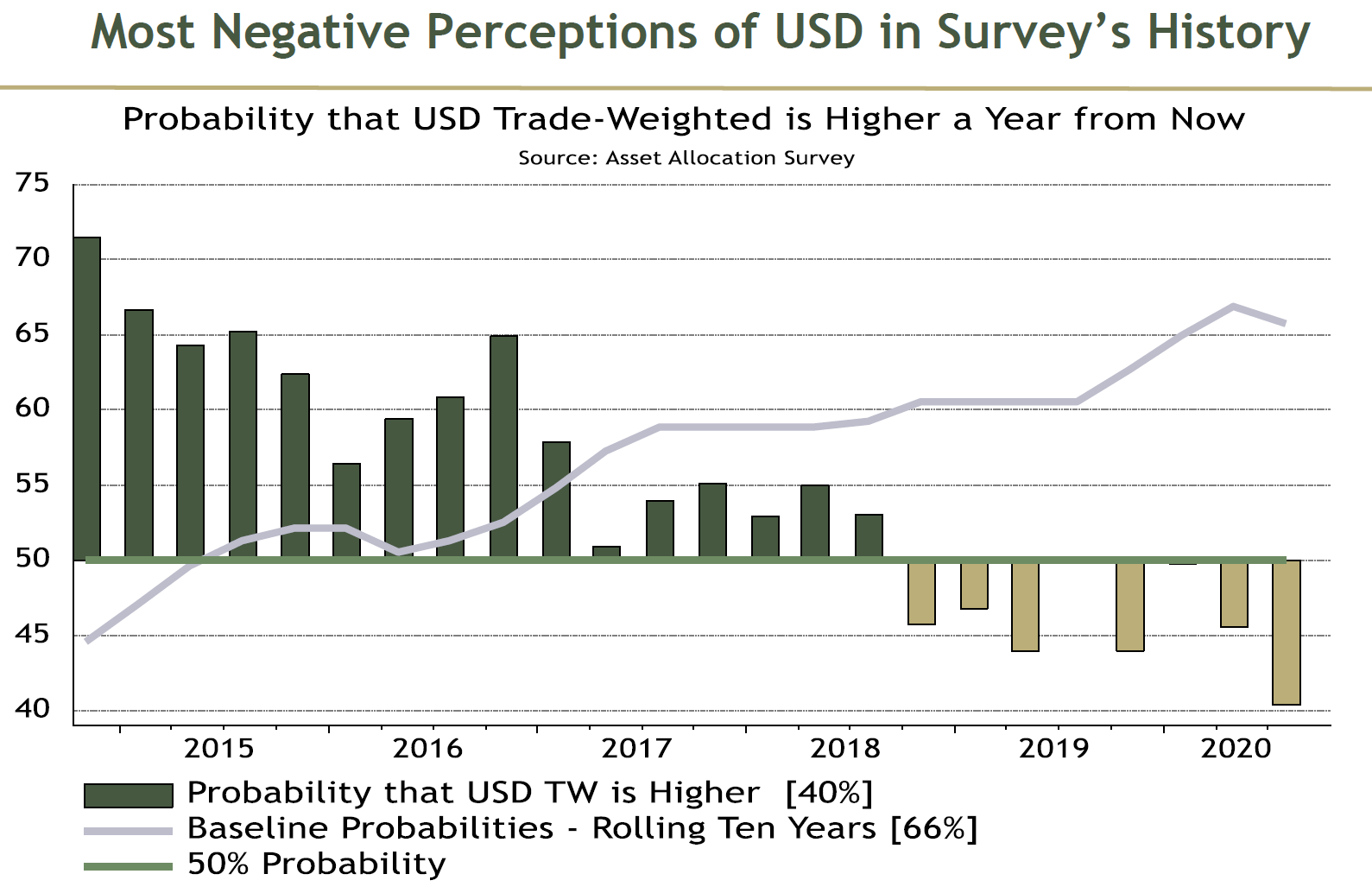

Incorrect as EverSeptember has brought a stock market correction. Very briefly, on an intraday basis, the S&P 500 was down 10% from its peak Monday. But it would be wrong to think of this as a continued correction. Until now, the September sell-off has been about correcting the extremes that the so-called FANG internet platform stocks had reached. They were falling while other parts of the market were recovering. On Monday, the FANGs gained again, while the average stock, represented by the S&P 500 equal-weighted index, fell:  What was going on? FANG popularity in large part rests on the perception that they are defensive. Thanks to their entrenched competitive position, and relative immunity to the pandemic, they are thought to offer safety. Meanwhile, the banks are the polar opposite. Aided by a positive economic cycle, banks also benefit from higher bond yields, which are nowhere to be seen. This weekend brought news of a fresh dose of scandal, with leaks of filings to the U.S. Treasury detailing some $2 trillion in suspicious transactions. That helped bring U.S. banks' share prices back down. European banks, which had been performing slightly better, had an even more brutal day:  Thus it makes sense to look at Monday's trading as a return to caution over the economy, after a few days when the move out of the FANGs had, counterintuitively, indicated cautious optimism. Meanwhile the bond market remained spectacularly calm. There was great excitement in March when the 10-year Treasury yield hit the "devil's number" of 0.666% on the anniversary of the day in 2009 when the S&P 500 hit its low for this century of 666. Since then, the 10-year yield has oscillated ever more tightly around that 0.666% level:  This is strange because the Federal Reserve isn't yet formally attempting to control 10-year yields, despite widespread speculation that it will start to do so before long. And views on inflation, usually a key component of nominal 10-year yields, have gone through huge changes during the .666 era. The following chart shows breakeven inflation rates for the next 10 years, and the 5-year 5-year forward rate, which shows expected inflation for 2025 to 2030:  Having recovered all their losses from the deflationary scare that the pandemic caused, inflation expectations have dropped noticeably since Fed Chairman Jerome Powell outlined plans to let prices move higher at the Jackson Hole virtual conference last month. This is a strange mix of phenomena. A recent survey of institutional investors' sentiment suggests immense optimism — despite the continuing freeze in the Treasury market. The quarterly survey by Absolute Strategy Research Ltd. of London is compiled by veterans of the fund manager survey run by BofA Securities Inc. It differs in having a panel of investors who put probabilities on different scenarios. On that basis, the survey found that on a range of "optimism" indicators, investors were as hopeful as they had been since the end of 2016, at the beginning of the Trump presidency:  This in turn was driven by a sharp increase in inflation expectations, albeit from lower levels. In both the euro zone and the U.S., a strong majority of respondents believe that central banks are going to succeed in kindling some inflation, despite their failure to do so after the 2008 financial crisis:  The swing toward optimism shows most clearly in the change in probabilities ascribed to different scenarios put forward by Absolute Strategy's researchers. The probability of a global recession has been slashed in the last three months, while higher corporate earnings are now seen as far more likely. This leads to a belief in a range of trades that had begun to work in the last few weeks, with the rest of the world more likely to outpace U.S. equities, gold less likely to prosper, and so on:  Some of the positions are startling at first sight. Comfortable majorities expect investment-grade credit to beat Treasuries (unsurprising with Treasury yields so low), but they also expect high-yield credit to beat investment-grade. For months, the concern has been that the acute liquidity problems caused by the Covid shutdown would eventually morph into a solvency crisis. Big investors no longer appear particularly worried:  Within equities, sentiment has swung toward a belief that the rest of the world can outperform the U.S., and that emerging markets can outperform developed markets:  That belief, in turn, is supported by the strongest conviction since the survey started in 2015 that the dollar is headed downward. That is generally a sign of positive risk appetite, as people no longer feel the need to buy into the dollar as a shelter.  There is still no coronavirus vaccine (andthe latest news has been discouraging). A much-feared "second wave" appears to be under way in Europe. Can people really be this optimistic? Maybe not. David Bowers of Absolute Strategy suggests the survey shouldn't be taken as signaling a true belief in a reflation trade. Instead, it shows investors are looking for how to hedge any possibility that the Fed is successful. As he puts it, this is about answering the question: "How do I make myself safe?" (Much the same was true of the rush to the FANGs earlier in the year.) Charles Cara of Absolute Strategy suggests that panelists fall into three different clusters, largely driven by their view on inflation. The biggest group, comprising 47%, "sees a strong rebound in activity which lifts commodity prices and triggers accelerating inflation around the world, even in Japan!" That entails rising bond yields, a steeper yield curve, greater confidence in credit, and greater belief that equities could beat bonds. As he summarized: In many ways these investors are expecting the trends of the last 3 months to continue. But they do expect a shift in momentum within the equity market. These investors are expecting stronger inflation to shift the winning stocks towards Cyclicals, Value stocks and EM equities.

The second largest cluster, at 29%, expects a rebound, but without much of an increase in inflation or in commodity prices. The Fed stays lenient, stocks beat bonds, credit stays calm: These investors still prefer cyclicals, wanting to ride the activity rebound, but are unwilling to favour the commodity rich equities such as the Value factor and non-US equities. Of all three groups this one sees the future equity trends as being most similar to the last 3 months.

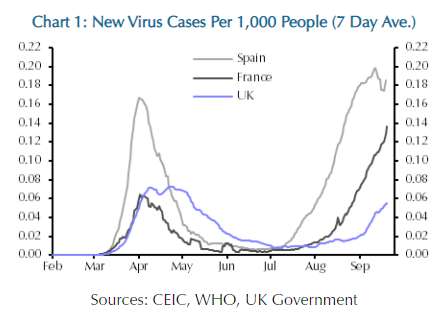

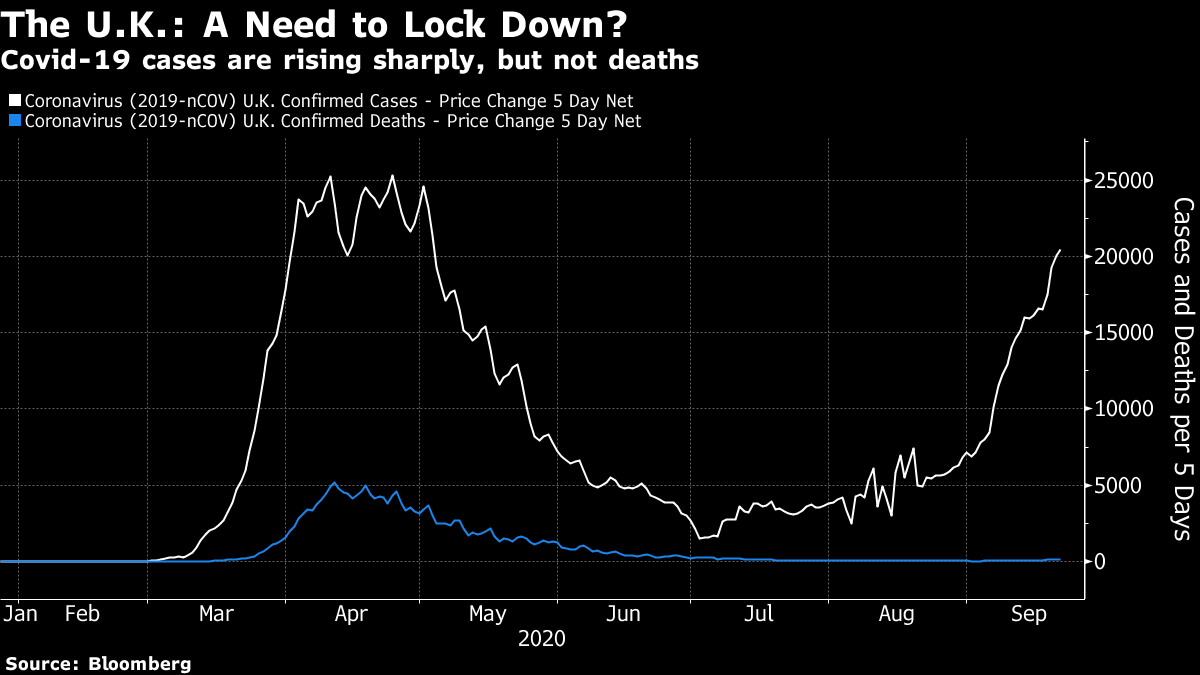

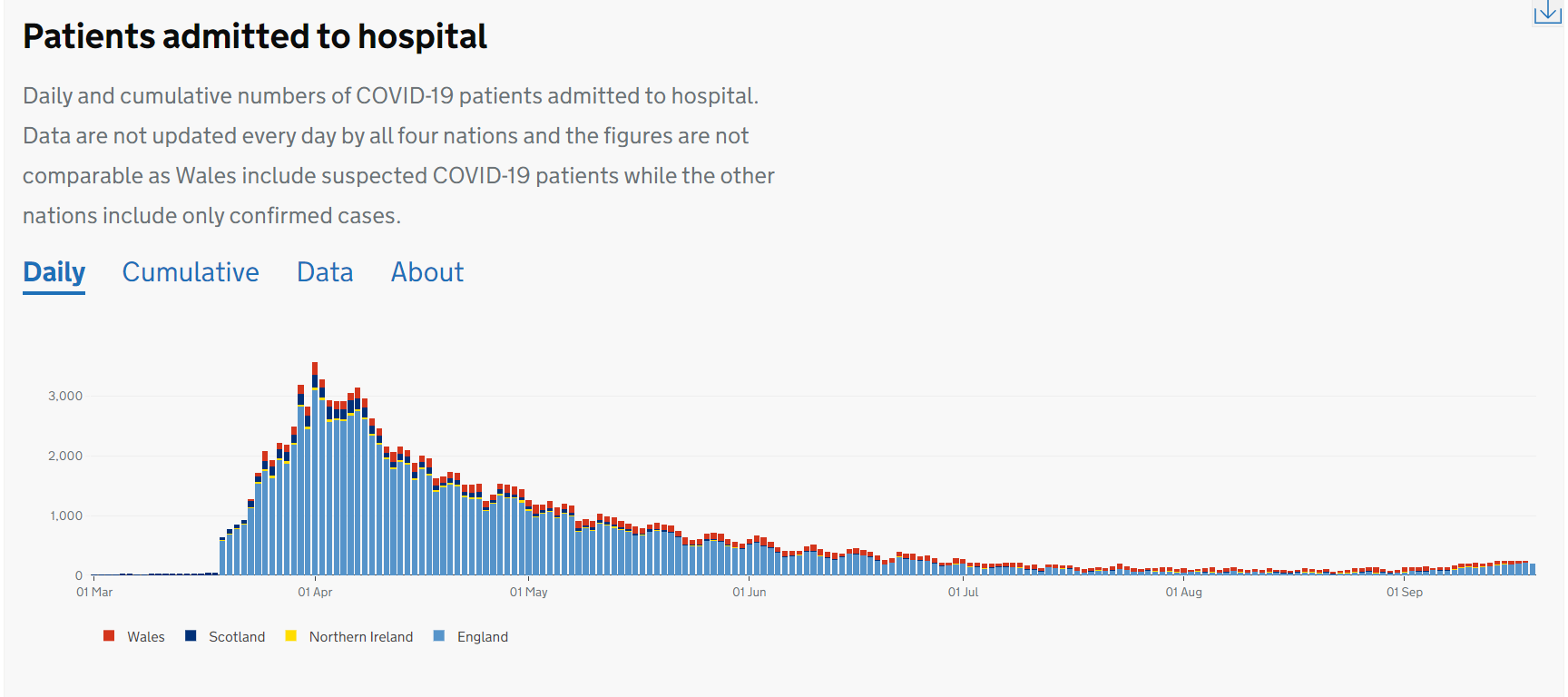

The final cluster is outright bearish on risk assets, but accounts for only 24%. They don't expect business confidence to recover (presumably because of a negative outlook on the pandemic) and therefore see more reason to fear a continuing recession. Some believe in stagflation, and others in deflationary depression, but agree on disliking credit and equity, and therefore reluctantly shelter in government bonds. This group still fears significant falls in equities, largely driven by a collapse in earnings multiples. Does all of this explain the weirdness of the last few weeks and months? No, but it helps. Second WaveMeanwhile, the most critical question concerning the chance of a strong economic recovery is approaching an answer: Will there be a "second wave" of the coronavirus? The question is much subtler than it was six months ago, when it was probably correct for a blindsided world to respond to a new and fast-spreading disease by shutting down. Now, there is greater knowledge, and much more complexity. So it is perhaps a little unnerving that the key test case on the "second wave" will be decided on by the U.K.'s prime minister, Boris Johnson. To simplify a sprawling debate, the case for a lockdown is contained in these figures, shown here in a chart from Capital Economics. New Covid cases per capita are higher than they were at the worst of the spring in both Spain and France while they are rising menacingly in the U.K.:  This is happening even though the U.K. ended up having one of the longest and most complete lockdowns the first time around. But are cases the best measure of the problem? In spring, cases were undercounted as officials struggled to organize testing. Now, more are being caught, despite serious problems with the U.K. testing system. Meanwhile deaths have barely risen yet, and remain far lower than they were in spring:  Hospitalizations show a just-discernible rise in the last few weeks, according to figures from Britain's National Health Service. The number of people so seriously ill that they need to go to hospital is still tiny compared to the spring, and there is no imminent danger of the system overflowing:  While deaths are obviously the most important measure, followed a long way behind by hospitalizations, the situation is complicated by the growing evidence that some people can suffer long-term debilitating consequences. There is still very little data on how widespread the problem is, and how long the effects can persist, but there are enough anecdotes to suggest that people under the age of 50 shouldn't be too cavalier about the risks of catching the virus — and that governments should go to some lengths to protect them. Johnson has to decide what to do. A second full lockdown looks hard to justify. Allowing the disease to continue expanding at its current rate looks similarly hard to justify. Leaks suggest he will aim for a compromise in which pubs and restaurants can still open, but will be required to close at 10 p.m. The debate over whether lockdowns only impeded countries from reaching "herd immunity" levels will also continue, although it is notable that the U.K. regions currently most affected were relatively spared earlier in the year. Will some more nuanced lockdown keep the disease sufficiently bottled up? Will Covid continue to grow less deadly over time? Or will greater understanding of longer-term effects force yet another change in direction? The answers to these imponderable questions matter to all of us. They will also determine the direction of asset markets. Survival TipsThe political rhetoric in the U.S. has grown so overheated that the only way to deal with it is to laugh. Monday brought the news that the attorney general is designating New York City (as well as Portland and Seattle) an "anarchist jurisdiction." The justification is that the city hasn't done enough to help the police deal with protesters, and this will provide an excuse for withholding federal funds. I used to live in London (another anarchist jurisdiction if you believed the Sex Pistols), which, according to President Trump, was "so radicalized that the police are afraid for their own lives." That comment spawned a rebuff from the entire British establishment, including a deathless comment from then-Mayor Boris Johnson: "The only reason I wouldn't go to some parts of New York is the real risk of meeting Donald Trump." Monday also brought the release of a new ad by Kelly Loeffler, Republican senatorial candidate in Georgia, in which she boasts of being "more conservative than Attila the Hun." This is literally in the "you couldn't make it up" territory. This "Racists for Trump" ad from Saturday Night Live, or even this negative ad on Mitt Romney also from SNL, are fictitious, but still not quite as ludicrous. Meanwhile, Verdi's treatment of Attila was much more dramatic. Following the RBG precedent, you can probably survive best by taking refuge in opera. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment