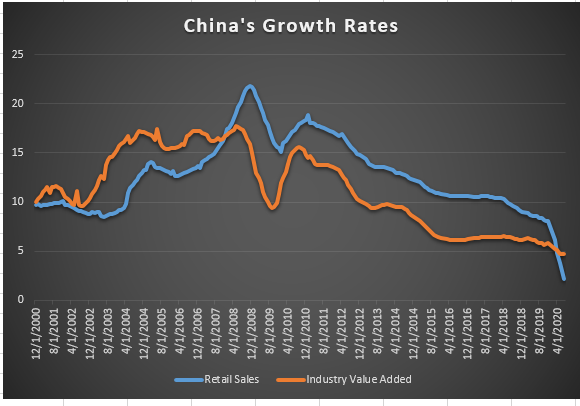

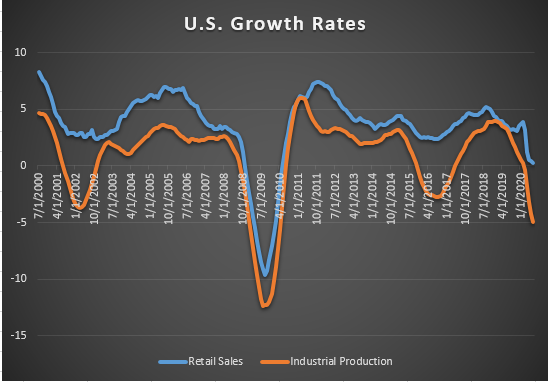

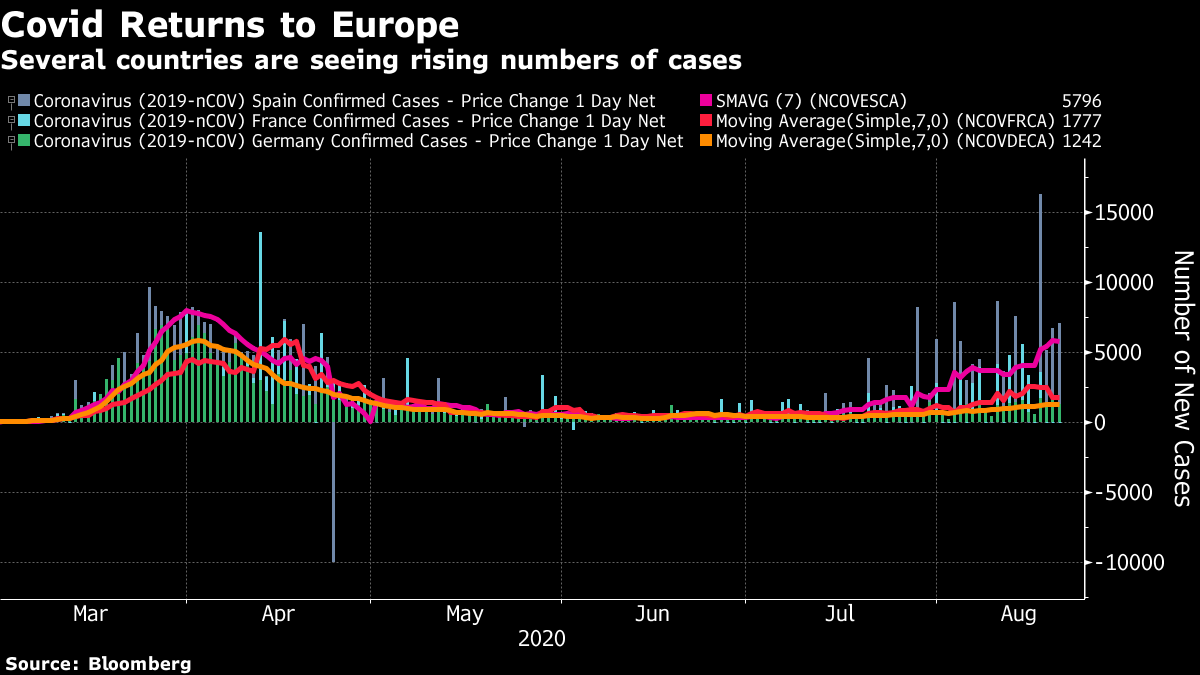

Prudent to Divest? If you run a university endowment in the U.S., you should think twice about investing in Chinese companies. That was the direct message from the U.S. State Department this week, and it could have a significant impact. A letter to universities tells them that it would be "prudent to divest from People's Republic of China firms' stocks in the likely outcome that enhanced listing standards lead to a wholesale de-listing of PRC firms from U.S. exchanges by the end of next year." Meanwhile, the U.S. administration is also clamping down on Huawei Technologies Co. in a way which my colleague Tim Culpan says threatens to kill the telecom equipment manfuacturer. It has also banned companies from doing any business with the online service Wechat, which is terrible news for its owner Tencent Holdings Ltd. — but also pretty bad for Apple Inc. All of these measures threaten much graver damage to the economies of both China and the U.S. than the tariffs that preoccupied the world for the year before Covid-19. They also make life very difficult for investors. When it comes to the managers of university endowments (full disclosure: I sit pro bono on an advisory committee that oversees the investments of my alma mater in the U.K.), they are used to political pressures, and have a fairly clear idea of how to respond. If a particular industry or country is unpopular with stakeholders (such as students, academics, or members of a union), it is often necessary to divest. The investment industry has made that much easier than it used to be. Any board of trustees under pressure to get out of fossil fuels or reduce their portfolio's carbon footprint can do so with index funds, often carefully calibrated to minimize any difference to returns. It isn't just the administration that's pushing disinvestment in China. Liberal students angered by the country's human rights abuses, and more conservative union members troubled by the way China has hollowed out the West's manufacturing base, will also prod them in the same direction. The only snag is that disinvesting is growing a little more painful in terms of the returns you might lose. The following chart maps MSCI's emerging markets excluding China index against its indexes for China and for the emerging markets as a whole:  The rest of the emerging markets is so correlated with China, and the country has historically had such a comparatively small share of the overall emerging-markets index, that for many years choosing a China-free version created no losses. With the nation's domestically traded A shares taking a larger share than they used to, that is no longer true — excluding China this year would have hurt. But as a general rule, it remains easy to get out. A simple way to get around the problem is to buy companies that are most exposed to China. There are plenty of them, and this creates a dilemma for policy makers trying to clamp down on what they see as Chinese misbehavior. The following chart shows how MSCI's index of 100 China-exposed companies in its developed-markets world index has fared over the last 10 years, relative to the MSCI World itself:  For a long time, as China's growth went off the boil, buying these companies signally failed to work. The last few months, as the country exited its Covid slowdown and resorted to a renewed credit-driven stimulus, they have enjoyed their best rally in years. The problem is whether these companies will be caught up in the U.S. campaign. Apple, for example, now worth more than $2 trillion according to Mr. Market, could do without too much more American hostility to China. Andy Rothman, the former U.S. diplomat who went on to a career in asset management in China, currently for the Matthews Asia fund management group, offers a useful assessment of how Chinese exposure helps corporate America: while China clearly has not lived up to all of its WTO commitments, it has done enough to enable GM to sell more cars in China than in the U.S. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, Nike enjoyed 22 consecutive quarters of double-digit revenue growth in China. And China is especially important to the U.S. semiconductor industry. Qualcomm, for example, earns about two-thirds of its global revenue in China. Profits from sales to China help finance continued R&D by America's tech companies. This leads to the further issue that China's (so far) successful stimulus has been a critical ingredient in global markets' recovery. That helps out a broad halo of companies. Industrial metals, for which China has effectively provided all the demand at the margin for many years, are surging. Copper is at its highest in two years, while the broader Bloomberg industrial metals index has also regained all the ground it lost during the slowdown earlier this year:  Messing with this has nasty implications for industrial sectors that are politically important for the U.S. administration. Steel and coal companies, both industries that have suffered dreadfully from the de-industrialization of the last few decades, are at the point where a China-driven cyclical pick-up in demand can help. Steel stocks are enjoying their strongest rally since China emerged from its last slowdown:  The more the American government pushes forward with this agenda, the more all investors, including managers of college endowments, will have to consider more bearish scenarios for global growth. China is far less exposed to exports than it was earlier in its expansion, and for many years now has generated greater economic activity by selling things to its own consumers. Rothman points out that gross value of exports now make up only 17% of China's GDP, half the 35% they accounted for in 2007, while over the last five years, net exports (deducting the value of imports) have, on average, contributed zero to China's GDP growth. As this chart (which I drew myself in Excel using Bloomberg data, thanks to some problems with my graphic software) shows, annual growth in retail sales in China has been faster than growth in industrial value added for years now — although industry has proved far more resilient during the current downturn, in part because China resorted to the old formula of juicing industrial growth with credit:  Incidentally, the equivalent exercise for the U.S. makes an intriguing contrast. Growth rates in absolute terms have, of course, been very much lower. But the Covid downturn has remarkably taken a greater toll on industrial production than on retail sales. It might be helpful to U.S. manufacturers to keep the very large Chinese market open to them:  There is, in U.S. convention season, evidently some political risk here. A President Biden is unlikely to be quite as aggressive or unpredictable in his China policy as President Trump has been. But getting tough on China is one of those rare causes that tends to unite a divided nation. Legislation to stop government pension funds from investing in China was sponsored by senators from both parties last year. Endowments and others would need to think about the political implications of buying into China even after a Democratic triumph in November. It is hard to see anything but further deterioration in U.S.-China relations this side of the election, or much in the way of improvement even if Biden wins. The incentives on endowment managers also point toward looking for China substitutes and maximizing their chance of a quiet life by limiting their direct exposure. The inescapable problem is that ultimately, some exposure to China cannot be avoided — and so any action that hurts China is going to hurt elsewhere. Europe and the Pandemic European stocks continue to underperform the U.S. Earlier in the summer, as the U.S. saw coronavirus cases surge, Europe began to shine. But now there is disquieting evidence that the virus is taking hold again, even after the continent's far more disciplined and apparently more effective lockdowns. The trend in Spain is particularly alarming, but the virus has plainly also awakened from its slumbers in Germany and France:  Much depends on whether Europe can bottle up the virus again. As it is, the continent's superior Covid performance to date has resulted in only a brief recovery in the long-running underperformance of European stocks. The following chart compares the FTSE-Eurofirst 300 to the version of the S&P 500 that excludes information technology and telecommunications, to avoid the strong FANG influence. On that basis, European stocks had their longest period above their 200-day moving average since 2017 while it appeared the continent had mastered the virus.  There is still nothing more important to the world economy, and its asset markets, than the virus. And there is still an awful lot that we don't know about it. Survival Tips As I have written, I spent last week trying to be a full-time Dad, exploring the natural wonders of upstate New York with my wife and children. It is always a privilege to do this. But an essay I've just read by the late Richard Feynman, a Nobel prize-winning physicist, suggests that it is possible for fathers to take their observations of wild New York to a different level. You can view a video of the interview on which the essay is based here. He recounts childhood summer trips to the Catskill Mountains to the north of New York City, where his Dad would join the family at weekends and take him for nature walks. His friends would then inveigle their fathers into taking their own walks: All the kids were playing in the field and one kid said to me, "See that bird, what kind of a bird is that?" And I said, "I haven't the slightest idea what kind of a bird it is." He says, "It's a brown throated thrush," or something, "Your father doesn't tell you anything." But it was the opposite: my father had taught me. Looking at a bird he says, " Do you know what that bird is? It's a brown throated thrush; but in Portuguese it's a… in Italian a..." he says "in Chinese it's a …, in Japanese a ..." etcetera. "Now, he says, "you know in all the languages you want to know what the name of that bird is and when you've finished with all that," he says, "you'll know absolutely nothing whatever about the bird. You only know about humans in different places and what they call the bird. Now," he says, "let's look at the bird." He had taught me to notice things. I dug around on the internet and discovered that there is no such thing as a brown-throated thrush, even though plenty of thrushes have brown throats. Ebird.org does however have some beautiful photos of red-throated thrushes, which you can view here. Unlike the elder Feynman, I have never managed to get my kids to look closely at a thrush, although I have told them the Latin name for the thrush genus, which they found very funny: Turdus. I do think Feynman gave his son quite a gift, in the ability to look at something for what it really is, rather than be content with putting a name on it and moving on. It's an inspiration for us all. Have a good weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment