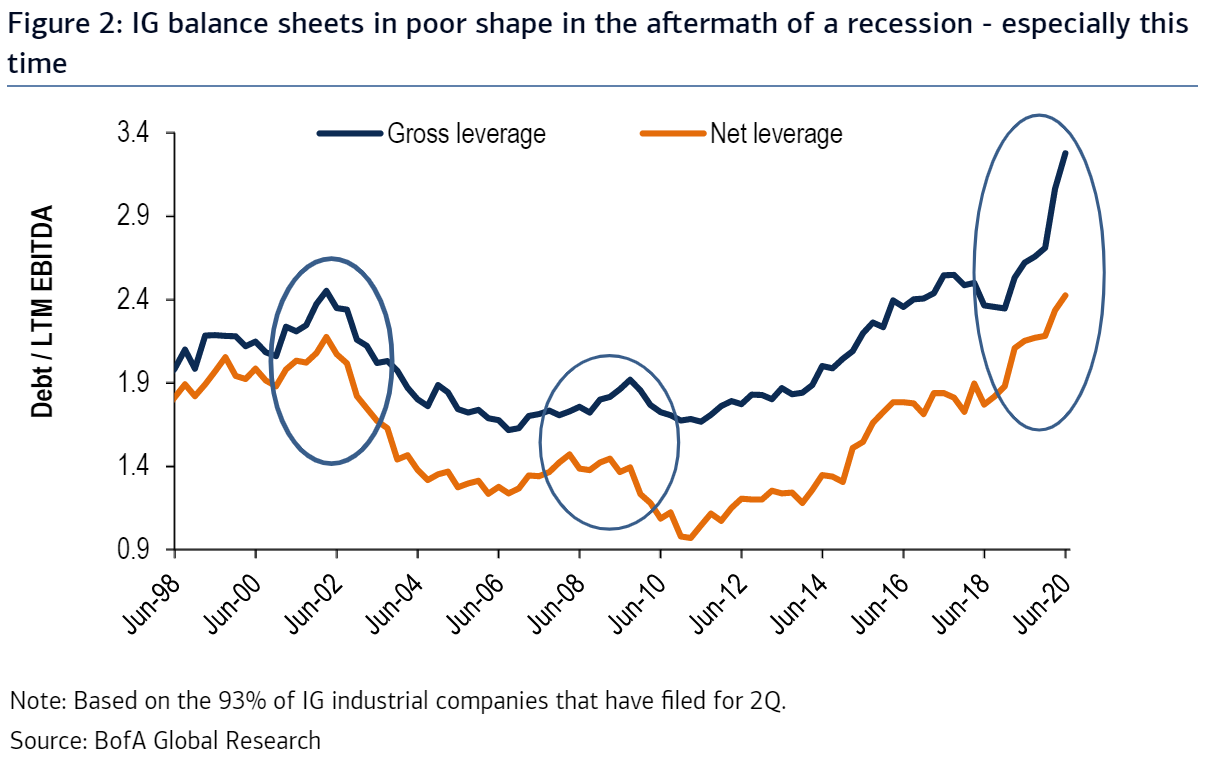

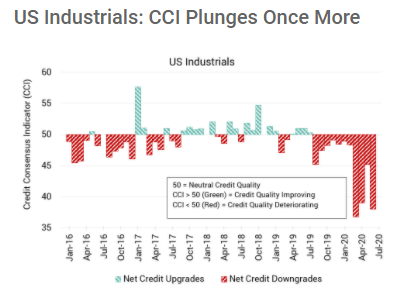

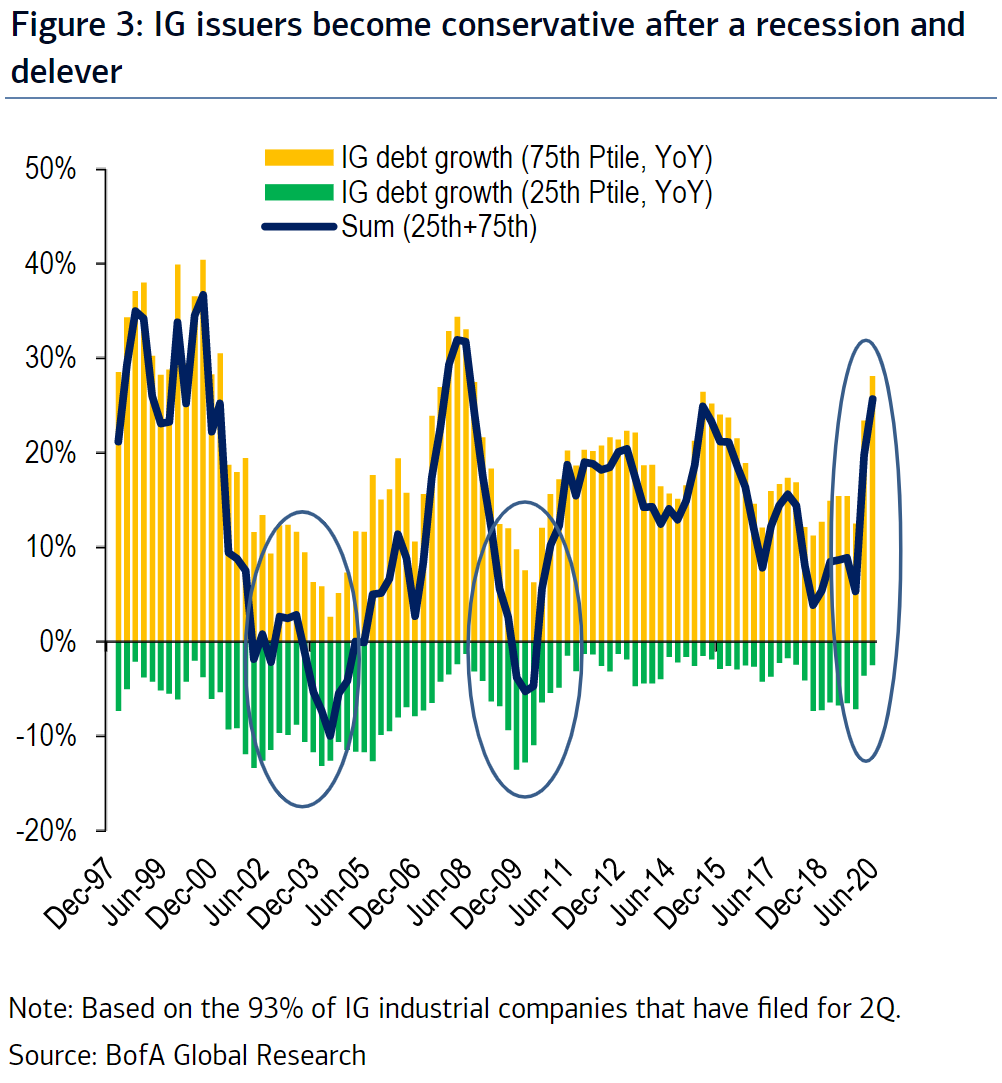

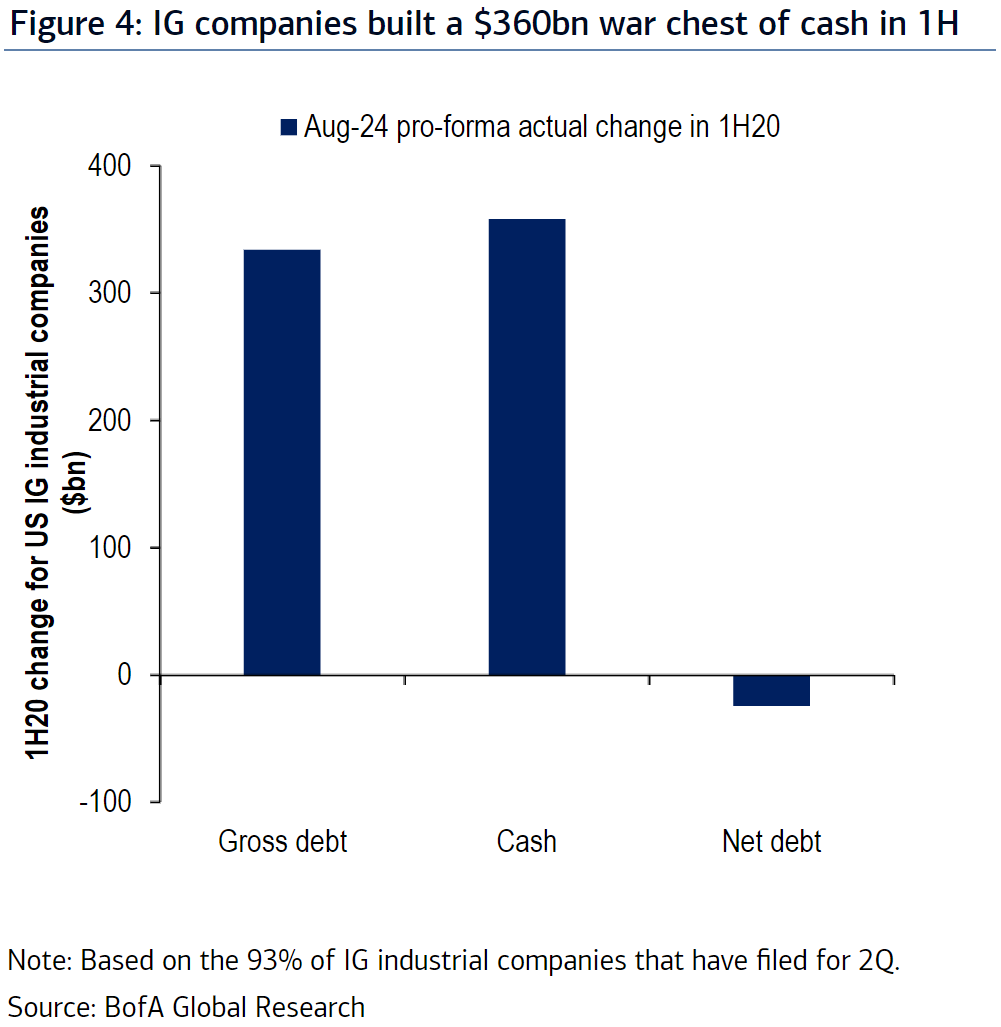

Credit Where Credit's Due If there is one financial risk that dogs the world, it concerns solvency. Will borrowers continue to be able to finance their debt? The terrifying liquidity crisis of March caused a lot of debt to be taken on to deal with the problem, and many companies and people have made do with far less revenue than they had expected since then. Credit problems in any sector can cause issues elsewhere, as the difficulties of subprime borrowers made clear a decade ago. But if we look at the strongest companies, things look good. Starting with investment-grade U.S. companies, judged by their debt as a proportion of earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization, this chart from BofA Securities Inc. shows that leverage has indeed increased dramatically. You would expect corporate balance sheets to be in bad shape in the aftermath of a recession; you wouldn't expect them to be this bad:  This has had an effect on credit-quality assessments. According to Credit Benchmark, which polls forward-looking opinions from more than 30,000 credit analysts, the quality of U.S. industrial companies is deteriorating as swiftly now as it was in the earlier stages of the pandemic:  This has straightforward implications for future behavior. Companies exiting a recession with a weak balance sheet and declining credit ratings tend to reduce leverage as rapidly as possible. This happened after the last two recessions, and it is reasonable to expect it again. Low rates make it easy to pay interest, but refinancing large quantities of debt remains a serious issue down the road, so companies will likely delever. That will presumably be at the expense of deals, or capital expenditure.  That said, companies have huge amounts of cash on hand. As this chart from BofA shows, their war chest is now around $360 billion. That cash represents the fruits of borrowing and asset sales to tide companies through the pandemic.  Similar trends are at work outside the U.S. This is Credit Benchmark's equivalent exercise for the European Union. Credit quality is still widely seen to be deteriorating, although the picture isn't quite as bad as it was a couple of months ago. These data probably don't yet take account of the disquieting recent increase in European Covid-19 cases:  In the U.K., where activity slowed for longer than in most countries on the continent, and where the end of the trade agreement with the EU looms at the end of the year, credit quality is deteriorating at its fastest rate yet:  What are the ramifications? In the short term, it may take a little longer for cheap companies to be snapped up by bigger ones, as acquirers won't want to use their cash. Unlike the last two major downturns, BofA shows that deal activity was rising leading into this episode. This is unlikely to continue:  None of this adds up to reason for wholesale alarm. It cost money to weather the crisis earlier this year, and the credit market is one of the vehicles through which those costs will be defrayed for larger companies. What of the high-yield bond market? Again, the picture isn't great, but is nowhere near as bad as feared in March. This chart from Jim Reid of Deutsche Bank AG compares the proportion of bank lending officers tightening standards, in the Fed's regular survey, with subsequent default rates in the high-yield market. It turns out that their actions are a good leading indicator:  If history is a guide, there are high-yield defaults ahead — probably getting into double digits by the end of next year. This isn't good, but as the world was bracing for the worst downturn in living memory not so long ago, it could be a lot worse. It suggests a dampener rather than a crisis. Reid does offer one negative take, in line with the critique he made in his annual study of defaults earlier this year. In essence, keeping defaults low can be a Faustian bargain, because it leads to more capital being misallocated to companies that cannot use it well. A little more creative destruction might be healthier. There are plenty of "zombie" companies out there, only able to service their debts because of ultra-low rates. This chart from Reid suggests that we might pay for avoiding a worse crisis now by suffering through more years of low productivity and drab growth:  I Could Be Wrong (Part I) It's vital in investing and life to ask yourself one question constantly: Could I be wrong? I still find it hard to break out of the negative mindset that most of us had earlier this year. Living at the American epicenter of the pandemic almost certainly causes me to exaggerate the public health dangers. The prevailing notion remains of a crippled economy. Thus it is most valuable to read a piece with the title Why I Was Wrong To Turn Bearish by Gavekal Research's co-founder Anatole Kaletsky (a former colleague). Kaletsky had been bullish for much of the post-crisis expansion, and turned bearish earlier this year, for understandable reasons. He now thinks he got that call wrong because he underestimated how far central banks and governments would go. As a result, he sees a chance for a "Keynesian phoenix" to arise from Covid, as the crisis at last jolts individuals, governments and companies into taking the right actions to build growth. Kaletsky's core economic argument is as follows: Economic theory suggests that in a world of excess capacity and mass unemployment, the present combination of vast government borrowing with monetary expansion will not fuel inflation until most of the excess capacity is exhausted. Instead, Keynesian fiscal stimulus financed with negative real interest rates will boost private consumption and investment, generating above-trend economic growth. That is indeed roughly what I remember from reading Samuelson's Economics, all those years ago. It is a straightforward and sensible argument. Yet the strength of markets is boggling the mind of many observers. Why turn bullish now, of all times? Here is Kaletsky's key historical analogy: Almost all economists and politicians at the end of World War II expected a global depression at least as bad as the 1930s, because millions of men in uniform were being demobilized and would find themselves unemployed. What happened instead, admittedly after several years of wrenching upheavals in the defeated countries, was an economic boom of unprecedented proportions and labor shortages on a scale never seen before. The pandemic has administered an economic shock to parallel a world war — but it is easy to forget that the last world war, once the conflict was over, administered a positive economic shock that lasted for decades. The parallel may fall down on the fact that the pandemic hasn't led to the destruction of much capital that needs to be replaced. There are other points in its favor, though. The last time the Federal Reserve resorted to blatant financial repression, holding yields low, was in the immediate post-war period. The history of the American economy in the 1950s and 1960s suggests it didn't work out too badly. Alternatively we could use the lens of the masterly British financial historians Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton in their history of markets in the 20th century, Triumph of the Optimists. It gets its title from a thought experiment. In 1950, only an extreme optimist would have confidently predicted all the good things that would happen over the next 50 years — economic miracles for Germany, Japan, the Tiger economies and by the end of the century China, while the cold war would be peacefully resolved. The 20th century turned out to be a triumph for the optimists, which is why markets rallied the way they did. Until now, the triumphalism of 2000 has seemed like an appropriate book-end. The developments of the last 20 years, and the steadily growing discontent throughout the Western world, would only have seemed likely to ultra-pessimists as we were welcoming in the millennium. And 2000 turned out to be a terrible time to invest. That, in very simple terms, is why Kaletsky thinks he was wrong to turn bearish — and why I fear I might be too bearish as well. I Could Be Wrong (Part 2) Thursday will see two hugely important speeches, from the chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, at the conference formerly known as Jackson Hole, and then by President Donald Trump at the Republican National Convention. Trump's acceptance speech is unlikely to move the dial on his chances of re-election. The situation in Kenosha, Wisconsin, may well turn out to be far more important than either of the parties' conventions. If we follow the script of 1968, the last year that was anything like this fractious and scary, then the violence could end up helping the Republicans. The critical difference is that they are the party in power this time. For now, we should be cautious about any political forecasts. Events between now and election day could still easily turn over what is a narrow lead for Joe Biden and the Democrats. As for Powell's speech, there is little need to speculate. But I do find the following chart from Deutsche's Jim Reid quite delicious. Commentators spend a lot of time pointing out that the Fed's actual policy looks nothing like the predictions it publishes each quarter in its "dot plot." Still, the equally clear judgments expressed by the fed funds futures market are no better. Over the last 20 years, traders have only occasionally been right about the near-term direction of rates, and then usually by coincidence:  Alan Greenspan cut more than the market expected after the dot-com bubble burst, then raised more than expected, while Ben Bernanke cut rates far more than anticipated, and left them low far longer than expected, and so on. Now there is virtual certainty that rates will stay low for as far as the eye can see. The markets and the dot plot agree on this. Why exactly should we expect them to be right this time? Survival Tips I passed a Starbucks today, and they already have pumpkin spice lattes available. Seasonal treats meant for Halloween and Thanksgiving are on offer in August. Is nothing sacred? They taste horrible, and I urge everyone to follow my own example and go to plucky local independent coffee shops that don't offer pumpkin spice instead. For a brilliant take on this, watch this piece from the weekend, produced by a fellow Englishman in New York, John Oliver. He first did this in 2017; and again in 2018; and 2019. You can also find John Oliver's original manifesto against all things pumpkin spice, recorded in 2014, here. Avoid it if you dislike the F-word. For a more financially relevant piece of comedy in the same vein, try this classic attack on CNBC by Jon Stewart (followed by a great interview with Joe Nocera, now a colleague at Bloomberg Opinion). It's a brilliant piece of satire that never gets old. For financial journalists, it provides all the warning you need to be skeptical at all times. And contrarians can delight in the fact that it was broadcast on the evening immediately after the S&P 500 made what turned out to be its lowest close in the last 24 years. When sentiment grows as strong as it was in early 2009, and inspires fiery satire like this, it is time to check your assumptions. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

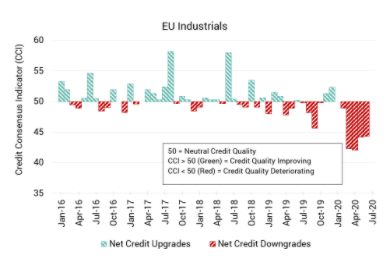

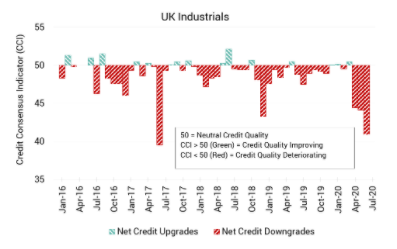

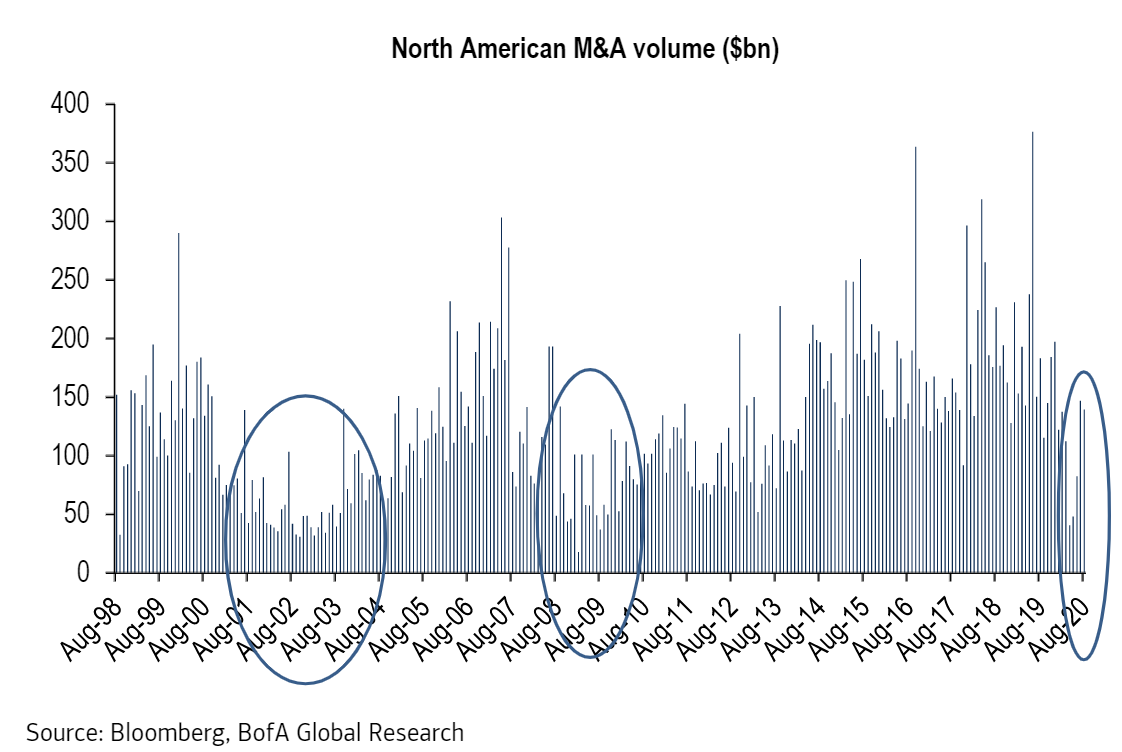

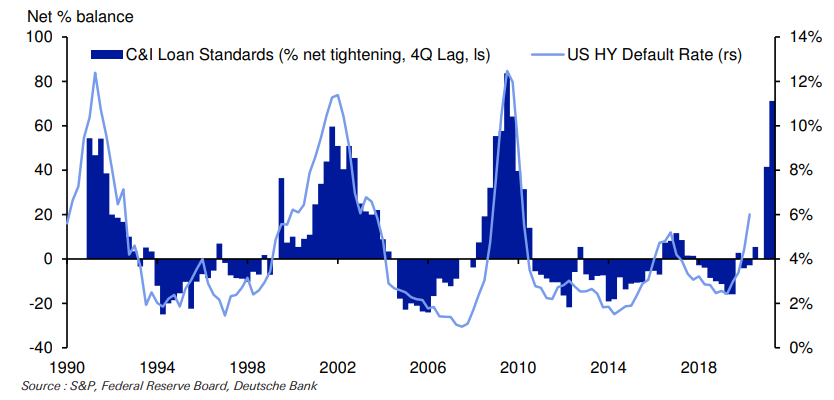

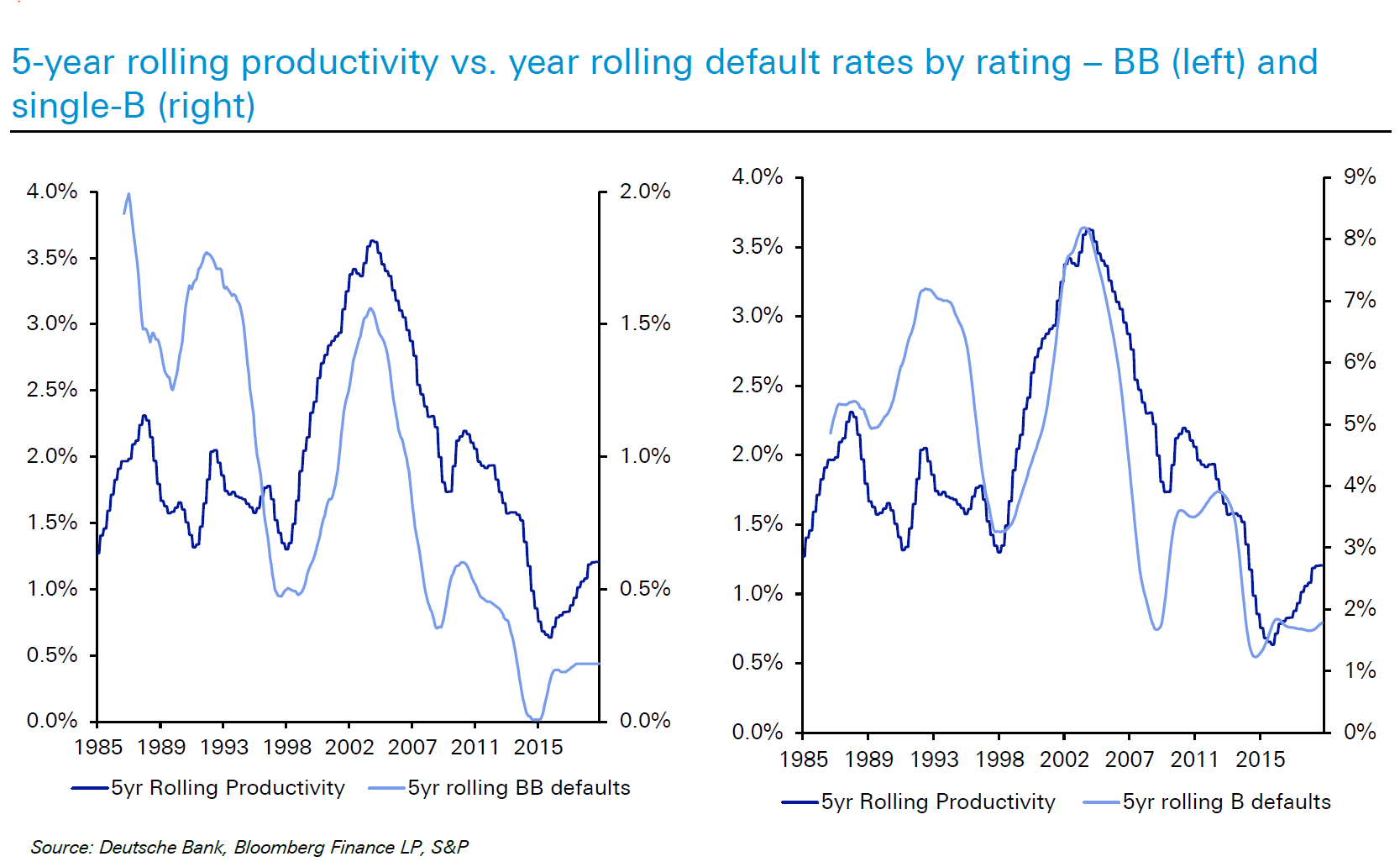

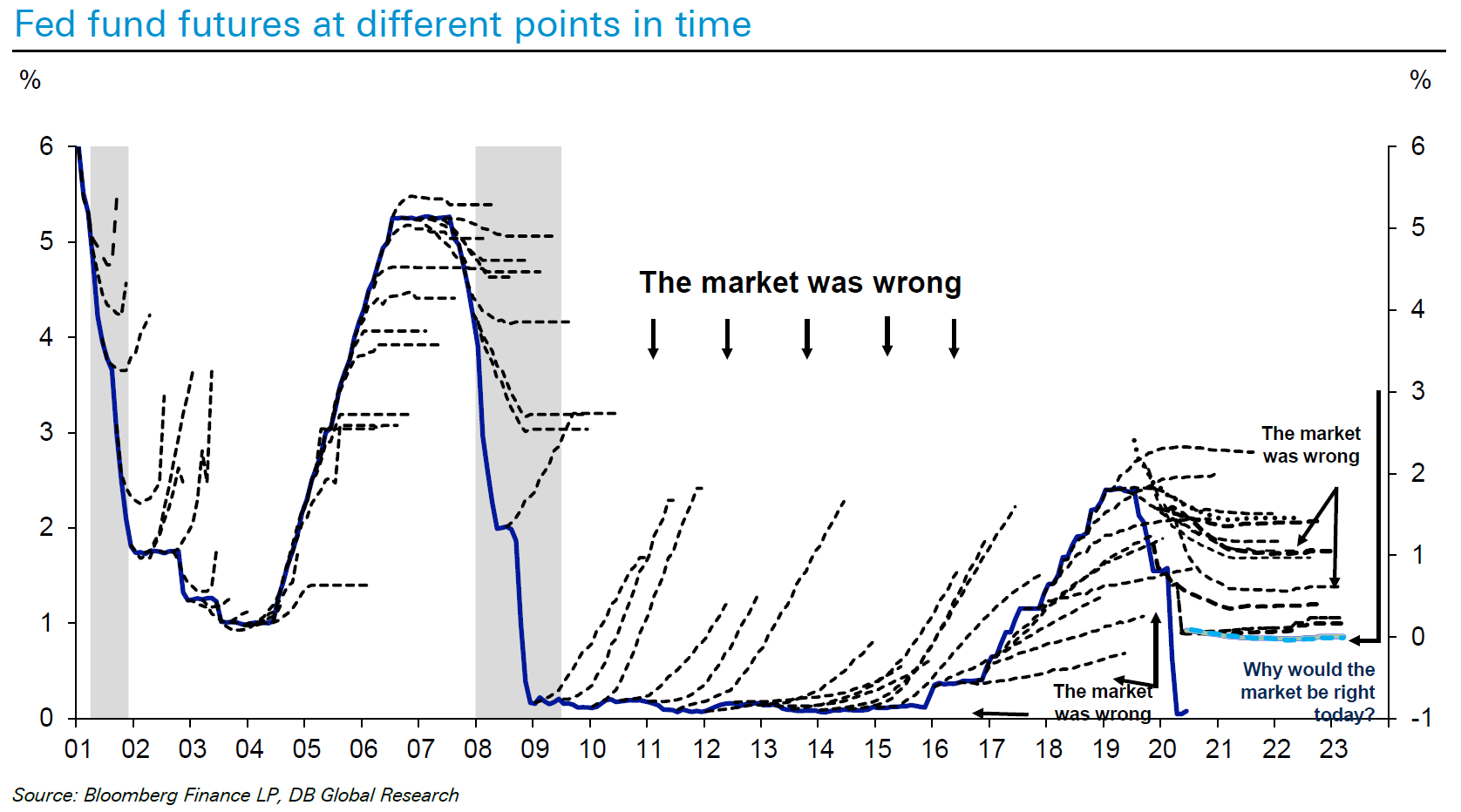

Post a Comment