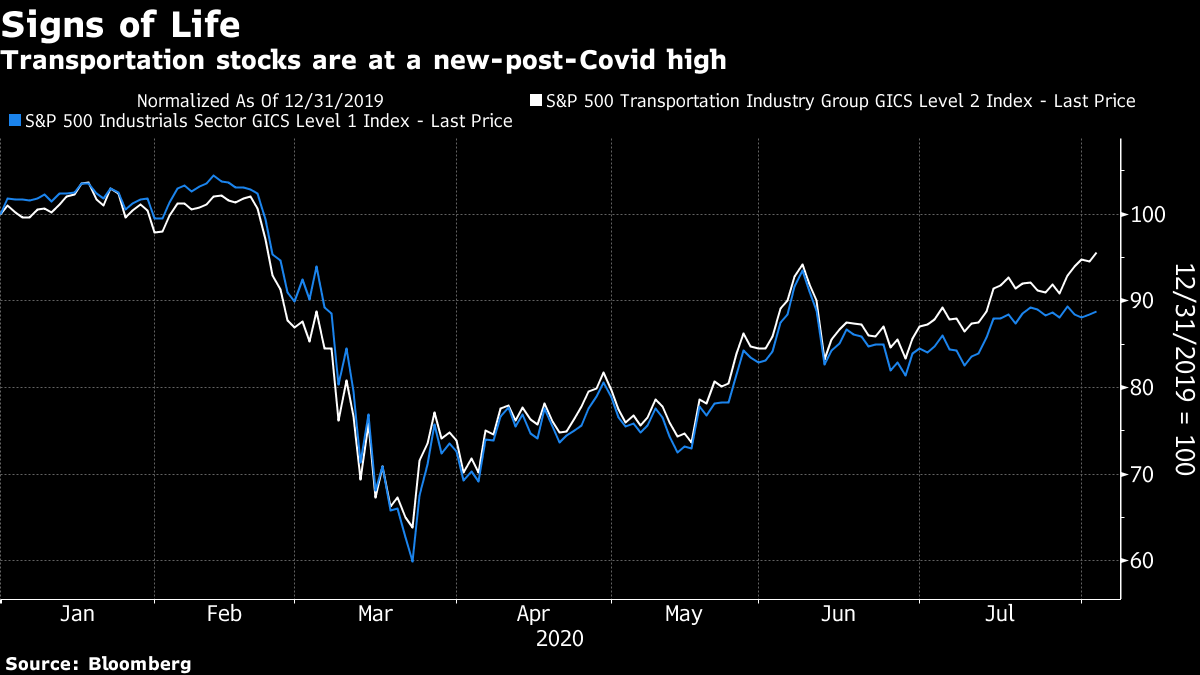

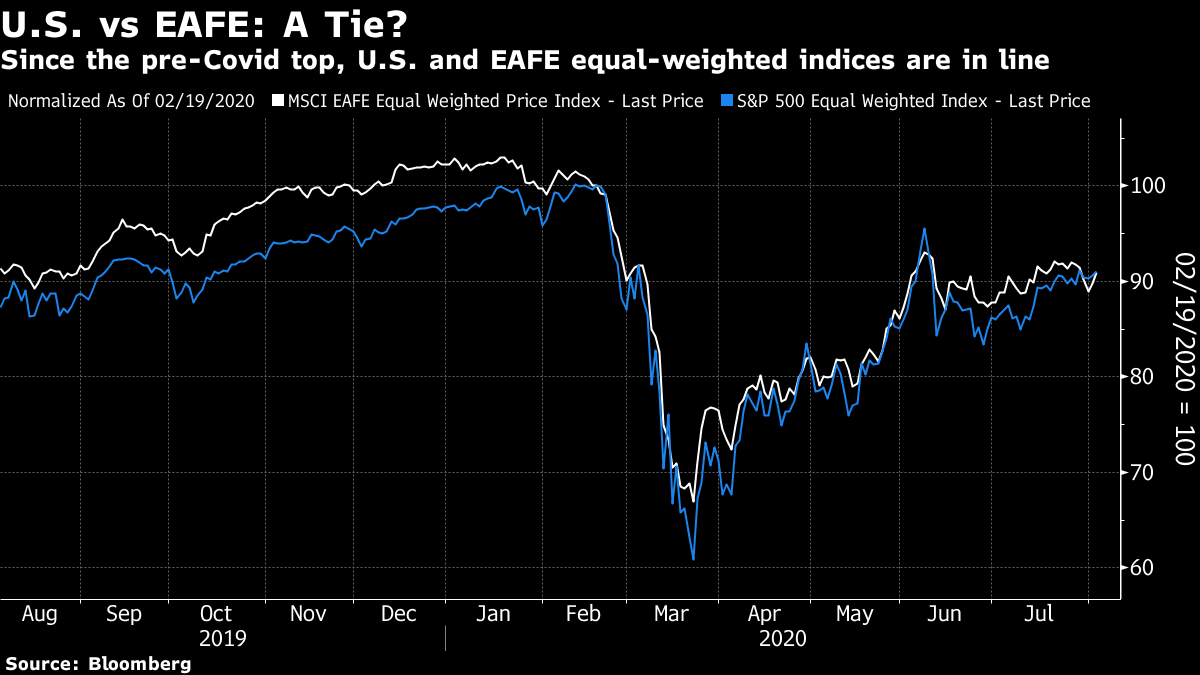

Forced to Be Free Easily overlooked in this febrile atmosphere, a debate over the roles and responsibilities of the investors entrusted with other people's money is coming to a head, and with it, a debate over the responsibility of those who manage companies. Do investors look merely at maximizing financial return without taking anything else into account? And should managers look for "shareholder value" — maximizing the value of the company's shares — or a more elusive concept of "stakeholder value," which takes into account the interests of employees, customers, suppliers and the local community? Miserable post-crisis conditions, with share prices rallying as economic growth remains anemic and social inequality deepens, have helped to tip the debate in favor of stakeholder investing. But a month ago, a new technical rule proposed by the U.S. Department of Labor for 401(k) retirement plan managers aimed to give shareholder value the force of law. It circumscribes the ability of investors to use environmental, social and governance, or ESG, factors when choosing investments. ESG is currently generating great excitement, and a lot of business, in the investment industry, and so a rule covering the vast U.S. defined contribution pension market could have a profound impact. The issue gains political force because it has been put forward by Labor Secretary Eugene Scalia, son of the late Supreme Court justice and fiery conservative Antonin Scalia. He introduced his proposal in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal. Scalia couched the proposal in terms of his duty to protect the rights of pension plans' members and ensure fund managers focus solely on investment returns. It gives the weight of law to the contention that investors should consider only "shareholder value" and not "stakeholder value." He concluded as follows: ESG investing often marches under the same banner as "stakeholder capitalism," which maintains that corporations owe obligations to a range of constituencies, not only their shareholders. Erisa [the Employee Retirement Income Security Act] requires something different of retirement plans, however: A fiduciary's duty is to retirees alone, because under Erisa one "social" goal trumps all others—retirement security for American workers. I am often skeptical about ESG. In particular, the disparity between rating services on which companies deserve to be regarded as good on ESG criteria (covered in this edition of Points of Return) suggests serious issues. It is also fair to be skeptical about a concept that is a great marketing point for active equity managers struggling to justify their existence amid the growth of passive investing and exchange-traded funds. But all of that said, there are still two broad and potent objections to Scalia's position, which jointly mean that it deserves to fail: Why shouldn't I take other factors than investment return into account? The past few years have seen a growth in the notion of pension-fund managers as "universal owners" charged with maximizing the well-being of members. What point is there in paying them a big pension if their retirement has to be spent amid deathly high temperatures and choking pollution? This line of thought can move beyond the notion of ESG as normally understood, to viewing pension managers as activists. Scalia's rule says flatly that it is unlawful for a fiduciary "to sacrifice return or accept additional risk to promote a public policy, political, or any other non-pecuniary goal." Is this really true? If it is a religious organization, surely they are entitled not to have their money put into investments that conflict with their beliefs? In ESG's early years, when it was known as "socially responsible" or "ethical" investing, it tended to be revolve around screening out stocks that particular people found immoral, such as tobacco, alcohol, or arms. These are non-pecuniary goals; should savers really be denied them? If it is a union fund, why not invest in line with the principles of the union that all the members freely joined? And as a pension fund is a way to give lots of little guys some collective big clout, why not use it? If members don't like Apartheid-era South Africa, shouldn't they be guaranteed they have no investments there? Or if New York City pension plans, covering the retirements of the many New Yorkers descended from Holocaust survivors, choose to threaten divestment from Swiss banks until they come up with a settlement over the issue of survivors' dormant accounts, as happened in 1998, why shouldn't they be free to do that? Much depends on the corporate governance of the pension fund, but if workers freely consent or even vote for such things, Scalia's rule appears to impinge on pensioners' freedom. If the first amendment right to free speech protects the right to spend money on political campaigns, shouldn't it also protect the right of pensioners to use their pension money for political or social purposes? "I'm taking ESG into account precisely because I want to maximize return." ESG is the subject of intense debate and research, but there's plenty of evidence that it can make you money. That may be because it is trendy and ESG stocks are hot; or because screening for environmental impact or bad governance effectively acts as a risk management filter; or because there is a pressing need for "green" environmental companies. Scalia's proposal short-circuits this debate and says in as many words that ESG investments will underperform: Some fiduciaries will select investments that are different from those they would have selected pre-rule. These selected investments' returns will generally tend to be higher over the long run. Also, as plans invest less in actively managed ESGs, they may instead select mutual funds with lower fees or passive index funds. The part in bold is an extremely contentious assertion. It may turn out to be true in the long run, but it should be subject to vigorous debate. It is far beyond the scope of the U.S. labor secretary to tell pension-fund managers which stocks to pick. Would he also tell them to go with value or growth, or avoid the FANGs, or invest in whatever is on the Robinhood.com leaderboard? As it stands, a large body of the industry is against Scalia — including many who might agree that investment shouldn't be used for political ends. "There's broad agreement that ESG integration is an innovation that's improving investment management and improving the ability to spot the risks and rewards inside of securities," says Ed Farrington, head of retirement and institutional sales for Natixis Investment Managers. "And there also seems to be agreement that we shouldn't be putting handcuffs around this. We should be welcoming it." Supporters of Scalia tend to offer no evidence that ESG investing is being abused or getting in the way of returns. They tend instead to find guilt by association. "Largely undefined, and heretofore largely unregulated," commented Justin Danhof, general counsel of the National Center for Public Policy Research and director of its Free Enterprise Project, in Breitbart.com, "ESG investing is favored among left-wing activists seeking social and political change through corporate action." As far as he was concerned, Scalia was merely "reminding pension managers that there is a place for politics and a place for sound investment decisions. When ESG investments put politics over profit, they are inappropriate." Danhof also attacked a piece by John Rekenthaler of Morningstar Inc., who is strongly skeptical of ESG investing, which claimed that ESG was being "throttled." Rekenthaler responded: "Why would somebody who advocates for "free enterprise" aggressively support a new government regulation that would restrict the freedoms of, ahem, free enterprises? I haven't yet sorted that one out. If you think you can explain how libertarian principles support the DOL's investment-restraining proposal (and can do so politely), feel free to send me a note." Rekenthaler is right. The Department of Labor has responsibility as a regulator, but this proposal is unduly prescriptive. For evidence, just look at the unusual coalition of opponents. Among more than 700 formal responses to the proposed rule, which can be found on the department's website, opponents include Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, a fabled critic of Wall Street and leader of the Democrats' left wing, and also numerous investment managers whose political sympathies lie elsewhere. This idea wouldn't survive a Democratic victory in the presidential election. But it also behooves Republicans to make sure that this doesn't happen. Record-Breakers Meanwhile, on the markets, more records fell on a day when our attention should have been turned to the Olympics. Aptly enough, gold hit a landmark, crossing $2,000 per ounce for the first time:  But if that seems like a signal of doom, note that the FANG stocks yet again set a record. Every time the NYSE Fang+ index suffers a dip, investors treat it as a time to buy:  And U.S. real yields fell to a fresh low. Ten-year TIPS, or Treasury inflation-protected securities, are offering the lowest yield since the securities have been on offer, at below minus 1%, while conventional 10-year Treasury yields dropped to an all-time low, save for a few hours on March 9 when the entire bond market appeared to have ceased to function:  How do we reconcile precious metals and bond prices that suggest disaster and stock prices that suggest we should be worried about a speculative bubble? Part of the answer is that yields are being driven by central bank activity, and help to justify higher prices for a range of other securities. Beyond that, there are some intriguing signs from the U.S. stock market. If not in full V-shaped recovery, important bellwether sectors are consolidating. For example, transportation stocks are at a new post-Covid high, and running ahead of industrial stocks:  If those industrials numbers look alarming, that is largely because of the influence of a few big companies. As Strategas pointed out in a recent note, on an equal-weighted basis the average S&P 500 industrials stock has done considerably better than the market cap-weighted index:  Equal-weighted indexes also cast more light on the FANGs, and the remarkable strength of the U.S. stock market. At least in the post-Covid environment, the market's strength compared to others is almost entirely thanks to the performance of the dominant internet groups. If we compare an equal-weighted version of the S&P 500 with an equal-weight version of the MSCI EAFE index, covering the rest of the world, they have been literally identical since the Feb. 19 top:  Meanwhile MSCI's equal-weight index for the rest of the world as a whole, including the emerging markets, has almost matched the cap-weighted S&P 500 since the pre-Covid top. It is far ahead of the average American stock:  The FANG phenomenon is strange. To understand how they can do so well in an environment where gold is $2,000 per ounce, we need to grasp two things. The first is that their exceptional profitability, shown in last week's results, is at least in part at the expense of other companies. The second is that they are rightly seen as defensive. On this basis, we can just about close the circle. Central banks are helping gold, and also supporting stocks; and the economic recovery that appears to be a little more robust in countries that have handled Covid-19 better than the U.S. has indeed translated into stronger performance by the average stock. But these are still strange days indeed. Survival Tips Returning to the FANGs, people are worried that they invade our privacy, and that security measures can be a problem. It's very easy to lock yourself out of your own device. In this regard, I have an interesting finding. My daughter Andie, in a moment of boredom, tried to teach her iPhone to recognize the cat's paw-print as a thumb-print that would open the phone. It worked. You can give your cat access to your iPhone if you wish.

What Andie hasn't worked out, unlike her siblings, is that her brother and sister now have access to her iPhone. All they need to do is enlist the cat to help.

The things one learns when working from home…. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment