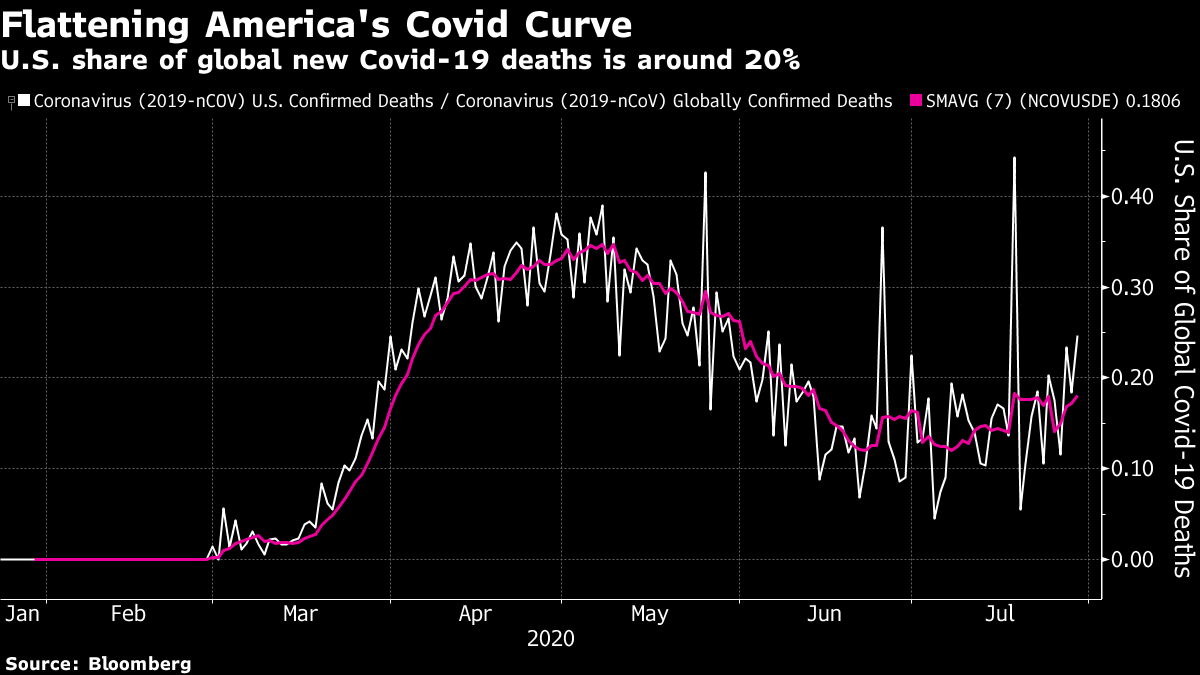

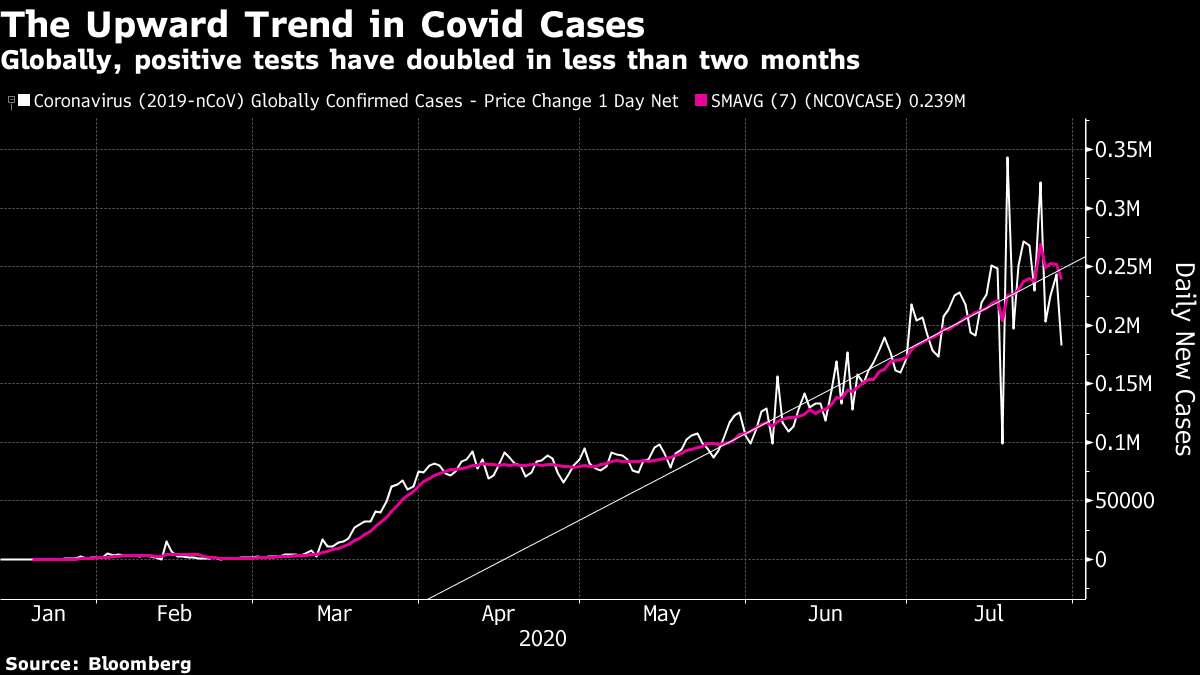

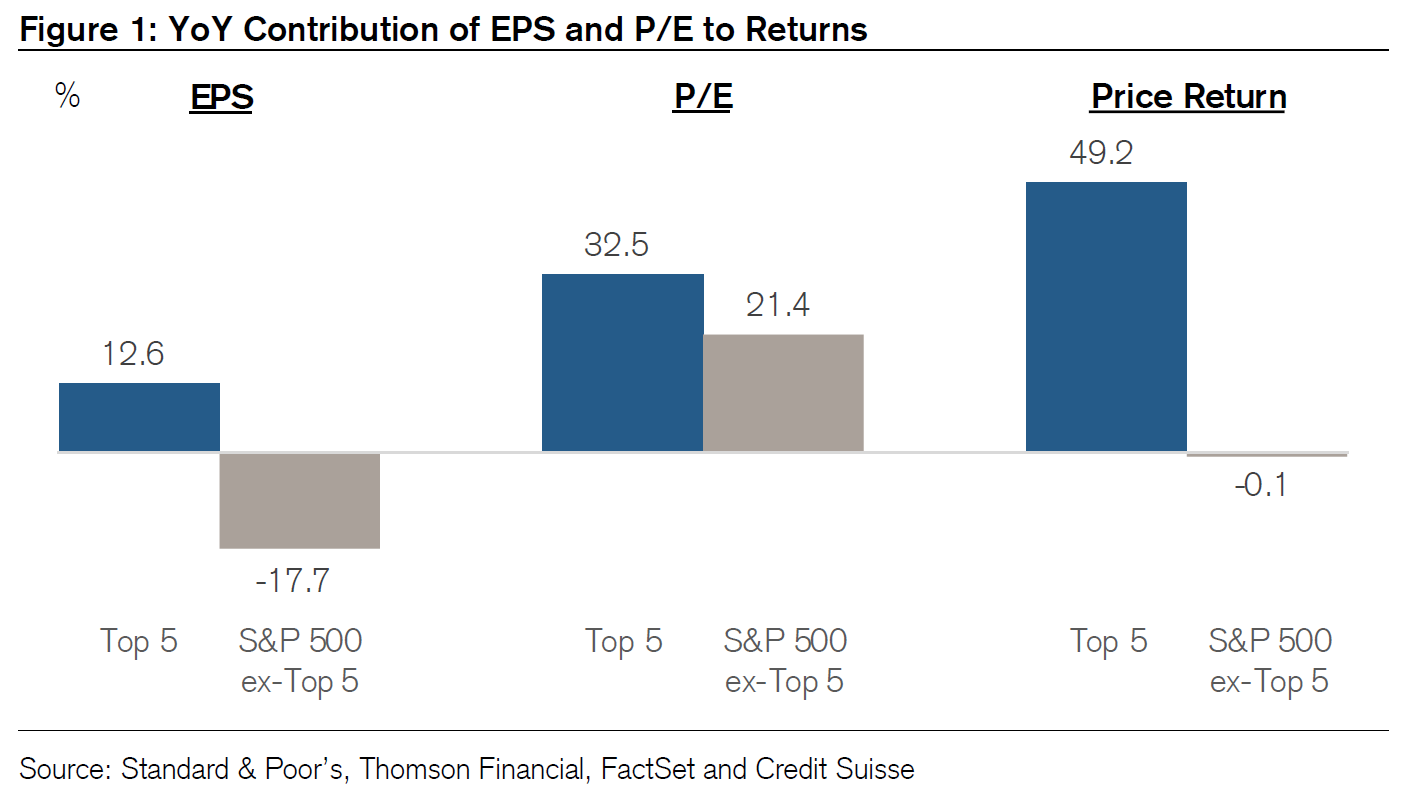

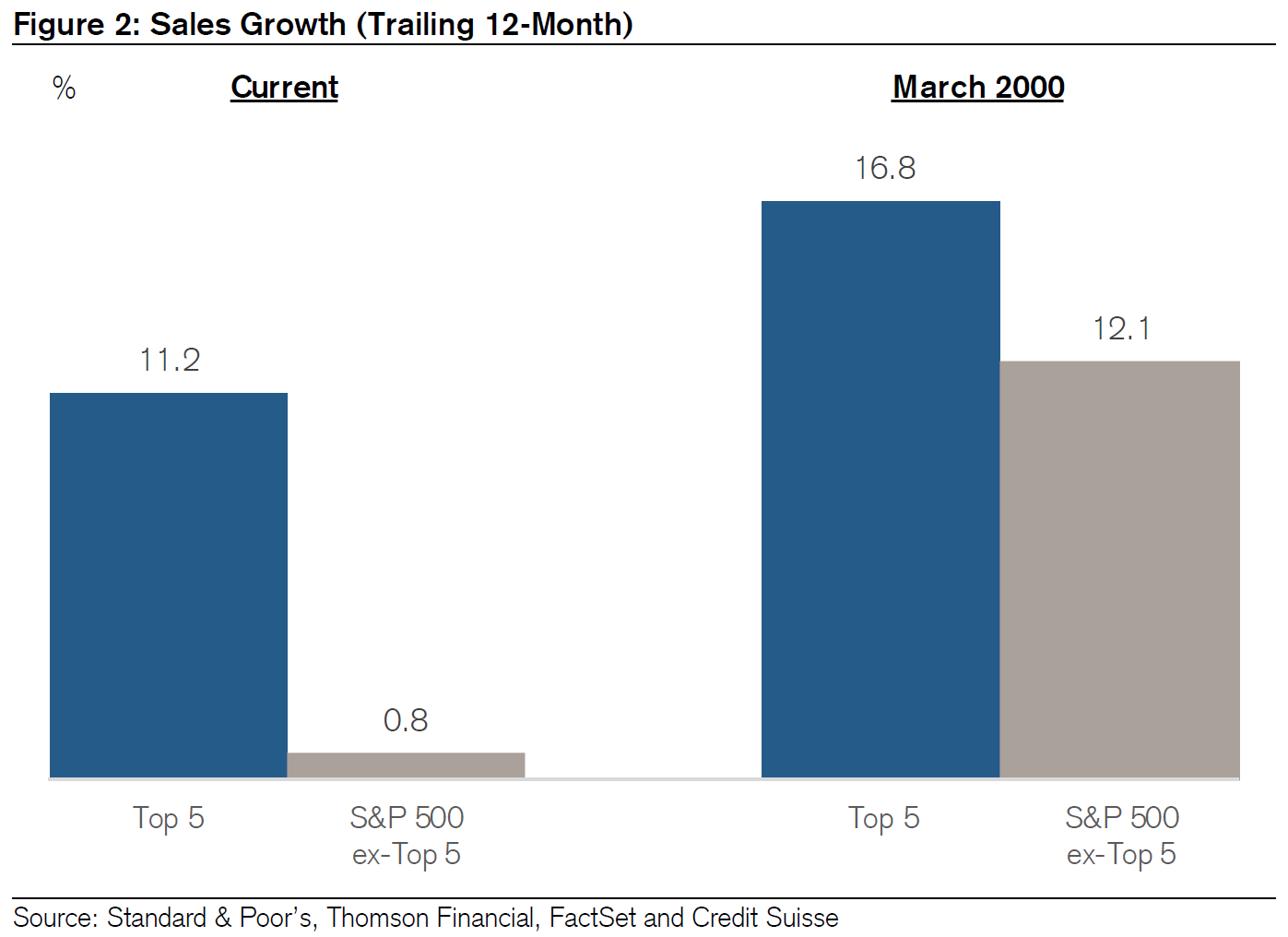

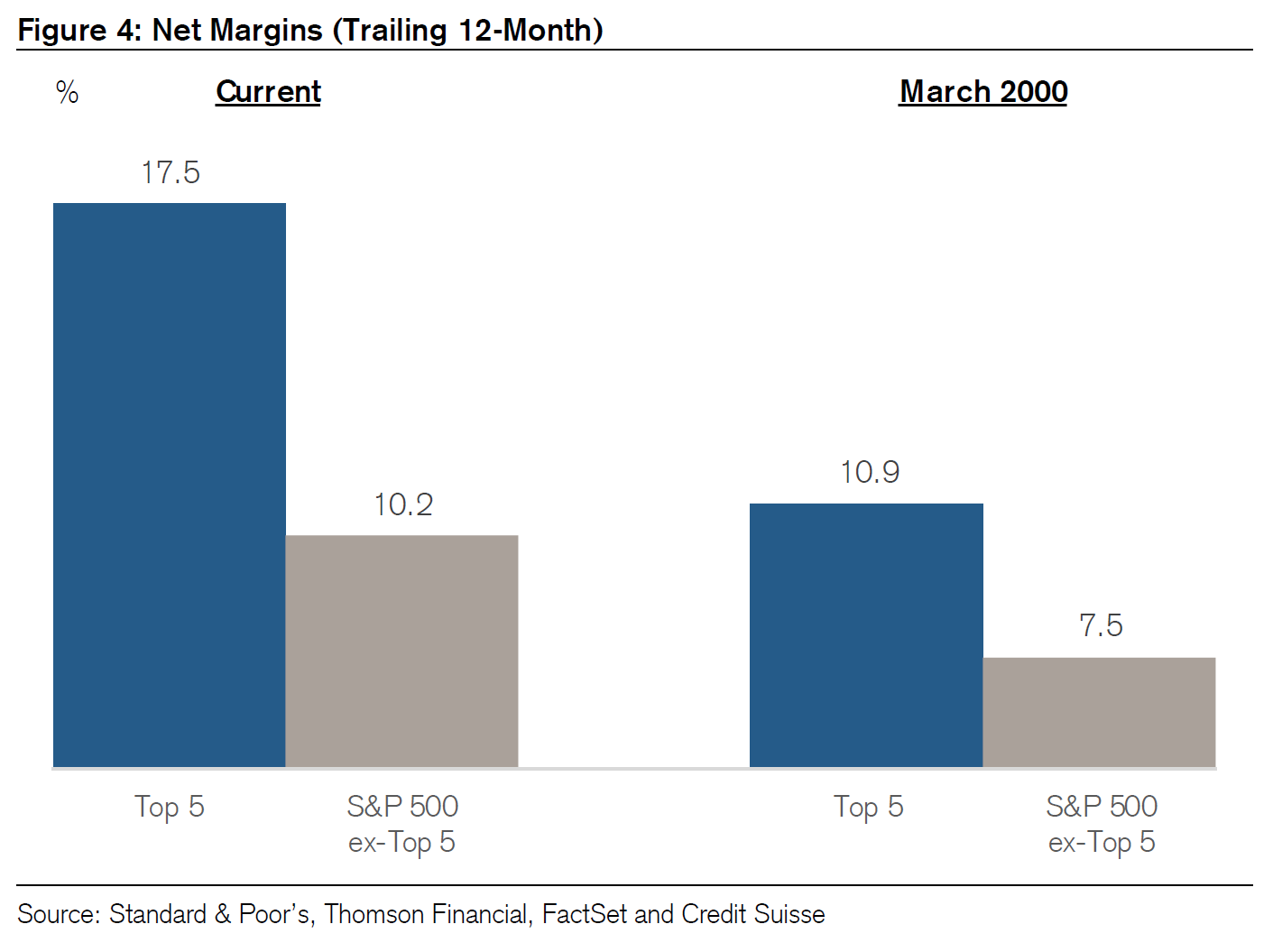

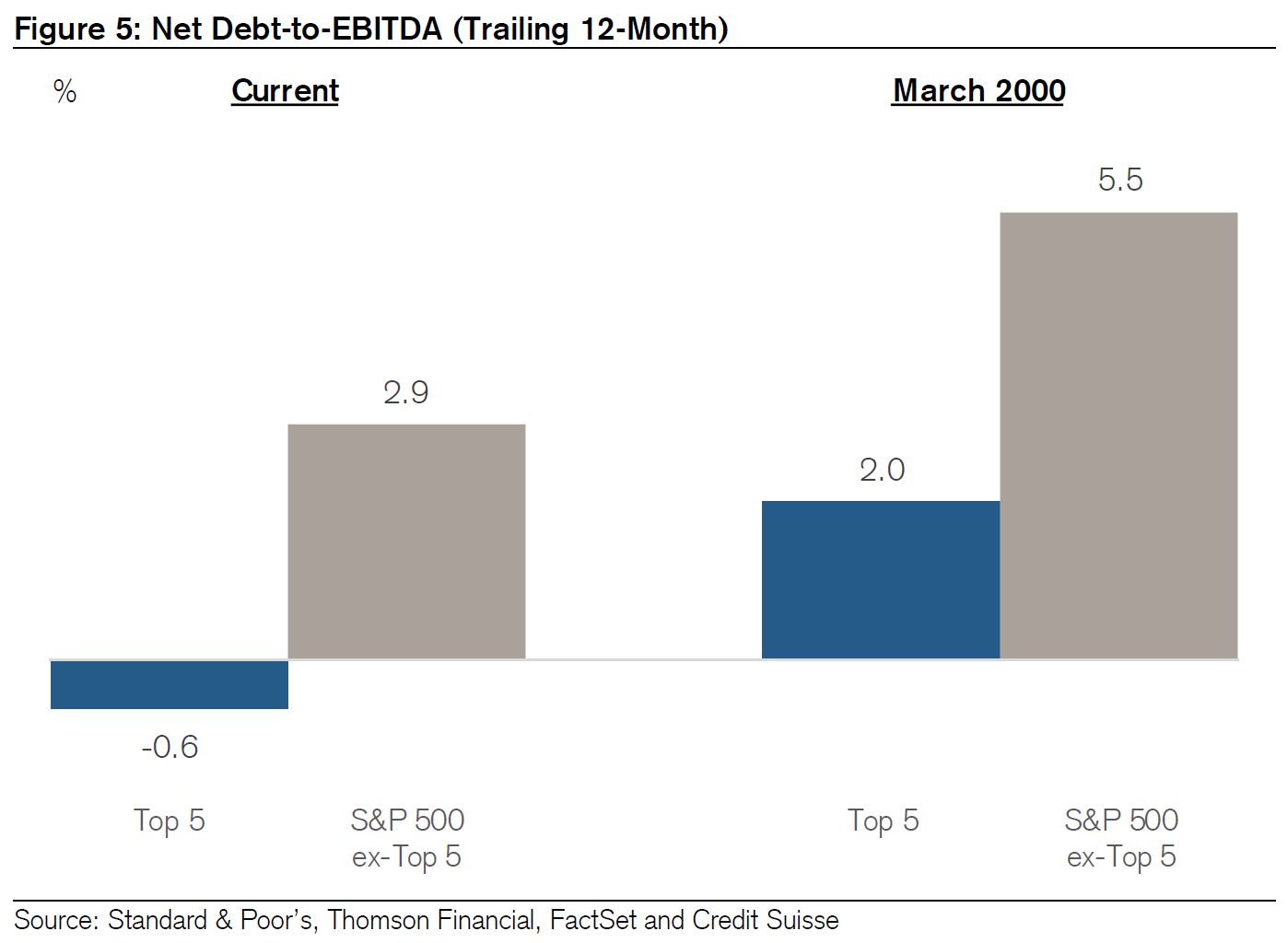

An Unpopularity ContestAn interesting inverse popularity contest is afoot. People are angry and looking for culprits. It tends to be the most successful or powerful who draw the most ire. Obviously the president, a divisive figure, gets a lot of criticism. But blaming everything on Donald Trump is too easy. The trends that are causing unrest long predate his election; indeed, they helped him get elected. Meanwhile, the last 24 hours have offered set-pieces to put a number of the most unpopular players in the spotlight. Let me take the rogues' gallery in turn. The Federal ReserveThe Fed is beloved by some for averting a crippling financial crisis in March, and then for keeping its foot on the pedal enough to erase virtually all the stock market's losses. It is already loathed by many who think it has gone too far this time, and that inflation and currency debasement lie in our future. Just look at gold, now at an all-time high in dollar terms. On Wednesday at least, Chairman Jerome Powell did a masterly job of meeting market expectations for a non-event. As expected, there were no significant announcements. As expected, the statement was unchanged, except to emphasize that the Fed is captive to the coronavirus. The only important change was the addition of this sentence: "The path of the economy will depend significantly on the course of the virus." This is already a strong candidate for the title of "most uncontroversial sentence a Fed chairman has ever uttered." In the press conference, and again as expected, all the emphasis was on the word "fiscal." The Fed has lifted markets almost single-handedly (much as it did after the 2008 crisis). It cannot perform the same trick on the economy without help from fiscal policy (another lesson from the aftermath of 2008) as well as the public health authorities. Powell wanted everyone to grasp that there were limits to what he could do without assistance from elected politicians. He was right about this. Debates over resorting to yield curve control, or to a more aggressive form of forward guidance, will continue and there is a good chance that we will hear more on these possibilities at the next meeting in September. As it stands, the package was enough to keep real yields and the dollar heading down, and stocks and gold heading up. In all cases the moves weren't dramatic. What really matters to these markets, as Powell said, is villain number one: the virus. Which brings us to: The VirusO.K., this is the one that everyone hates the most. There's really no contest. The wave in the Sun Belt appears to be cresting, and the worry now moves on to the virus's reappearance in other parts of the world that seemed to have extinguished it (like Australia or Spain), and also in some northern U.S. states. The disease is getting less deadly as it spreads, but barely any less disruptive. And, disappointingly, it doesn't seem to be deterred by warm weather. There are some fascinating and well-documented theories out there that it might be under control already, and that we might not even need a vaccine to beat it. A few more weeks of evidence are needed. For now, I'd suggest two curves, both easily generated on your Bloomberg terminal, are the key indicators to watch. First, much anti-dollar sentiment is driven by the belief that the U.S. has a specific and serious problem dealing with the virus. The following chart shows U.S. daily deaths as a proportion of global deaths, which might be the best relative indicator. Given the U.S. population and wealth, its share of global fatalities is shamefully high. But at less than 20% of the global daily total, if we use a seven-day moving average, it is still far less than in April. If the share doesn't rise much from here, that might well qualify as a positive for the dollar.  Then there is the trend in global cases. Increases in testing over the last few months mean we need to treat this data carefully, but we can assume that most countries are testing about to the limit of their capability by now. The pattern is clear: Cases rose sharply in March, leveled off in April and May, and have been on a remarkably consistent and steady upward trend since then. If we keep following the trend line I drew on the following graph, then daily new cases will hit half a million for the first time on Christmas Eve. We all have strong reasons to hope that the virus comes under control well before then; the health of our equity investments is on the list (albeit a long way down).  The consistency of the upward trend is disconcerting, and helps to explain some of the risk-averse signs in world markets. Somehow, it will have to come under control, or the economy will suffer (regardless of whether governments resort to official lockdowns). The Fangs and Congress The latest political theater in Congress pitted two of the most popularly blamed groups against each other. On one side, the CEOs of four of the five biggest companies in the world (Alphabet Inc.'s Google, Facebook Inc., Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc.; Microsoft Corp. is exempt from such proceedings these days, for some reason). On the other, Congress. Nine years ago, an influx of Tea Party representatives inflicted the "debt ceiling" negotiations on us at exactly this time of year. Now, thanks to the unplanned and unhoped-for resurgence of Covid-19, and to a misjudged piece of brinkmanship, Congress is again dangling the prospect of falling off a "fiscal cliff," with proposals to make big cuts in jobless benefits just as unemployment is rising again. There are arguments for this; the immediate economic impact would be awful. The tenor of the hearings, with members of both parties convinced that social media was biased in favor of the other, only heightened the sense of dysfunction. It's easy to see that incumbent politicians — in the U.S. and much of the rest of the world — are a big part of the problem. But apart from grievances over bias and fake news, the representatives also wanted to talk about anti-competitive practices and antitrust. On this, the Fangs really have a difficult case to answer. As all the indications are that Democrats under a President Biden might actually attempt to put that question to them, the following graphics from a beautifully concise note from Credit Suisse Group AG's U.S. equity strategist Jonathan Golub are worth reading. First of all, if we look at the last year in isolation, we see that the top five companies (today's congressional witnesses plus Microsoft) have increased earnings per share by 12.6% from a year earlier, while the figure for the rest of the S&P has fallen by 17.7%. As for share price returns, the big five have returned 49.2% over 12 months — and the de-Fanged S&P has gained nothing at all:  This doesn't necessarily suggest an antitrust case. But when we move on to sales growth, we discover the big five have pulled in an extra 11.2% over the last year, while the rest have gained only 0.8%. This is very unusual. If we go back to 2000, the peak of the last great unbalanced market, the then-top five increased sales by 16.8%, but the rest still managed to grow by 12.1%. (One key difference between this period and 2000 is that there was a genuinely strong economy then):  This raises the possibility, aired by a number of representatives, that the big five are growing at the expense of the rest, or maybe even of the economy itself. That begins to seem much more plausible when we examine profit margins, and then look at the equivalent numbers from March 2000:  Margins like this suggest the big five have very wide economic moats — which is Warren Buffett's favorite euphemism for saying that they have an entrenched and probably unfair competitive advantage. Now for balance sheets. Amazingly, the big five are collectively cash-positive — they have negative net debt. Again this isn't like the rest, and it isn't like 2000.  All five are good and well-run companies that provide services people want to use. But these numbers are breathtaking. They also seem flatly impossible, unless they are benefiting from effective monopolies. And the numbers of the rest suggest that the big five are sucking some of the oxygen from them. For a qualitative comparison, the difference in tone between this hearing and the heady atmosphere of 2000 could not be greater. Back then, virtually all of the exciting new companies were treated much the way Tesla Inc. is today; they were a matter of belief, attracted deep devotion, and relied on starry visions of the future. The Fangs today are viewed with a hushed and rather grudging respect. They are not loved (with the partial exception of Apple, but even that company doesn't inspire the devotion it once did). As for Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, the only one of this week's players who also had a starring role in 2000, the change is also palpable and symbolic. Back then he was a loud, jovial and charismatic presence, with a laugh that would reverberate through the newsroom whenever he arrived for a briefing. Now he is the richest man in the world, and appeared sober and serious. The Bezos of 2000 turned out to be a great entrepreneur who would beat all the doubters time and again. But now he is obviously the man in possession, and the politicians may well decide that his grip has to be prized loose. In short: All the rogues in the gallery deserve some opprobrium. But the one that matters most is the virus. Survival TipsIt's stinking hot in Manhattan, such that the family is now sheltering in the two rooms in the apartment where the air-conditioning actually keeps the atmosphere cold. As there is a lot of background noise, I have only managed to write this by putting on headphones and blasting myself with familiar music. So. Here is a playlist of albums that a) never grow old in the re-listening, and b) are so familiar that you can work through them. In Desert Island Discs fashion I feel obliged to offer eight. I didn't get through all of them tonight though: "The Suburbs:" Arcade Fire "The Stone Roses:" The Stone Roses "London Calling:" The Clash"(What's The Story) Morning Glory:" Oasis "Achtung Baby:" U2 "Revolver:" The Beatles "The White Album:" The Beatles "Strangeways Here We Come:" The Smiths The Beatles get two because they're the Beatles. I mastered the temptation to offer up "Goodbye Jumbo" by World Party (favorite of young adulthood), "Organisation" by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark (favorite of early adolescence), "Hamilton" (favorite of my children in early adolescence), "Cold Fact" by Rodriguez (new discovery of working-from-home), and any number of greatest hits compilations. Joy Division doesn't work as background music, and classical needs to be turned up uncomfortably loud to block out the family. Yes, from this list you can tell my age, gender, nationality, level of education, and ethnicity. You don't need a brilliantly clever social media algorithm to work them out. But most of you probably knew all of those anyway. And if you're going to survive in these circumstances you may as well listen to something comfortable. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment