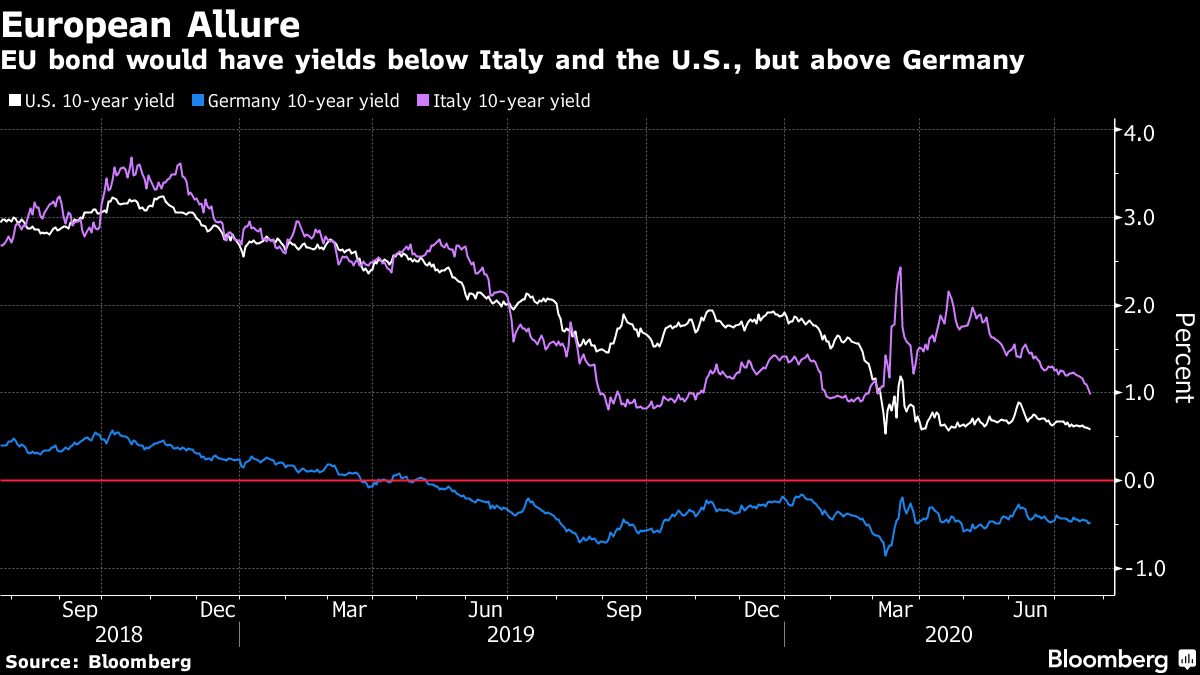

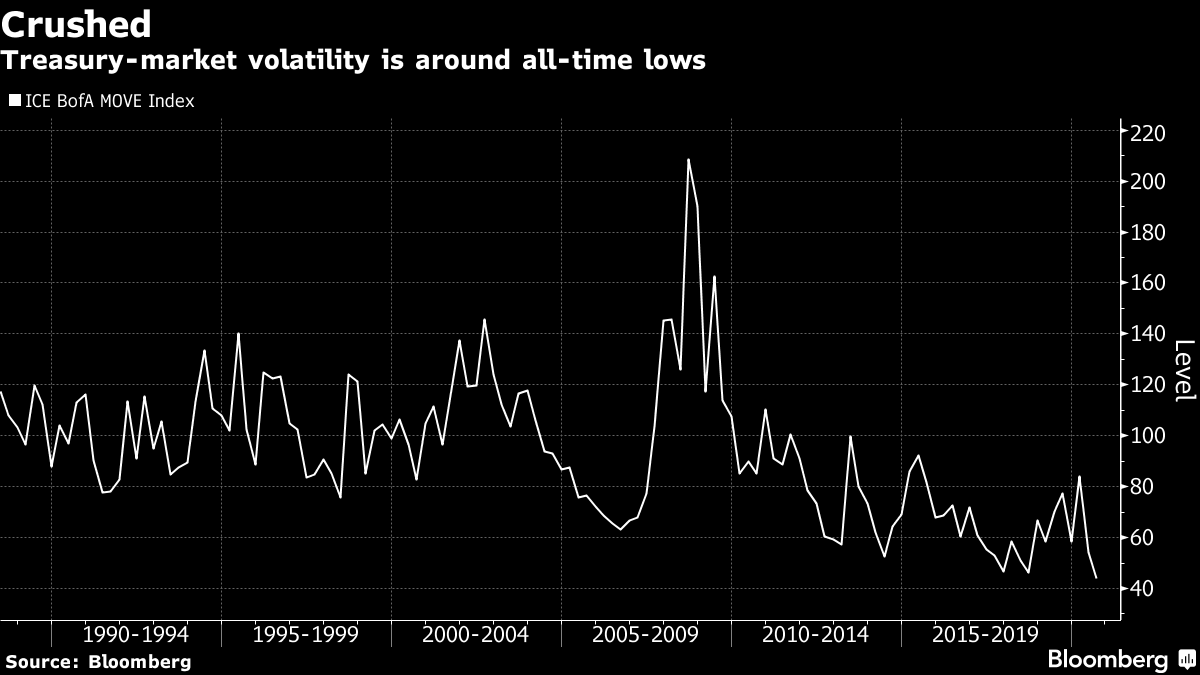

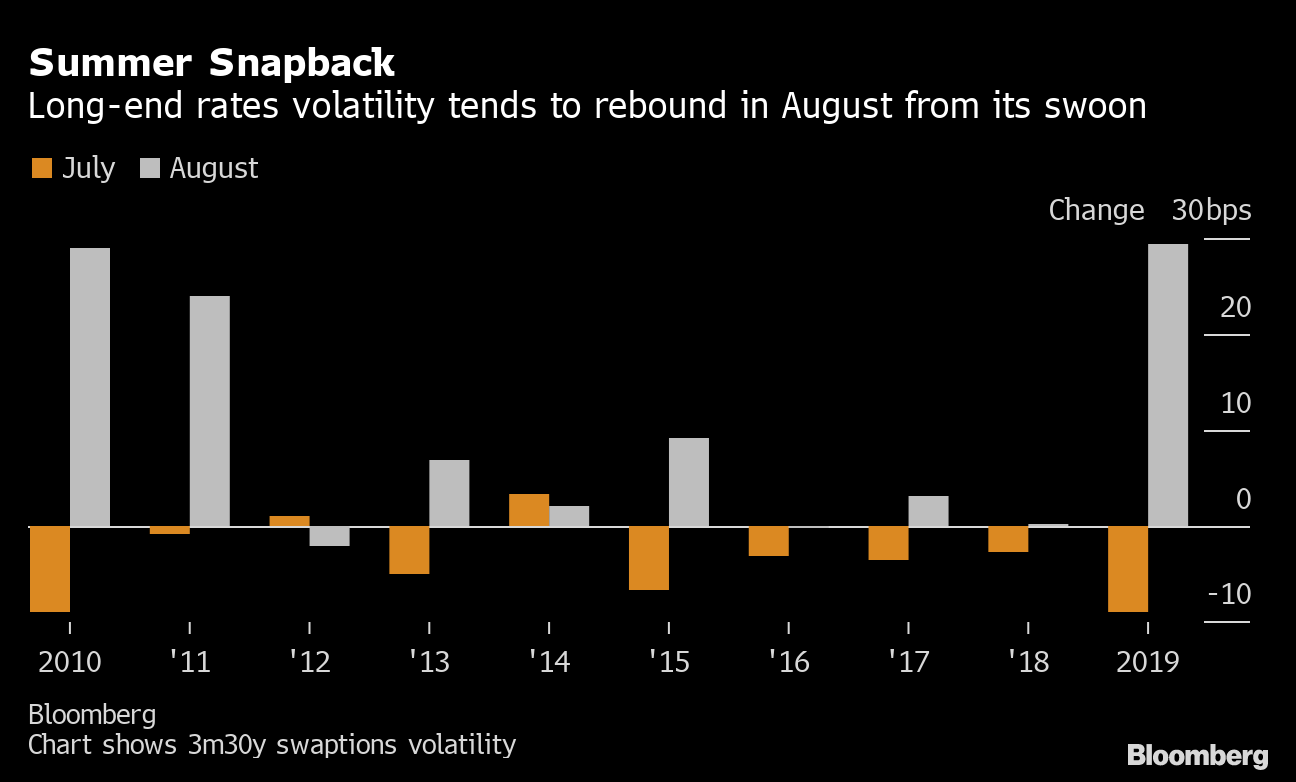

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that is generally against remakes, as there's a shortage of perfect movies in this world. –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter. The Good News: A European Renaissance The pandemic has done for the European Union what the past decade's string of crises sometimes couldn't: compelled action. EU lawmakers have bridged long-insurmountable differences to approve a 750 billion-euro ($870 billion) fund to combat the devastating economic effects of the pandemic. More than half of it is in the form of grants and about 30% must go to green investments It's also laden with hopes for the birth of a new, fiscally-integrated bloc. That's still a long way off, but perhaps not as distant as it seemed until very recently. The new bonds won't be the first the union has issued -- it's managed deals for targeted efforts such as Ireland's and Portugal's bailouts about a decade ago -- but this program dwarfs the roughly 52 billion euros of existing debt. The EU seems to have risen from the ashes of its sovereign-debt crisis and the Brexit schism, laying the groundwork for an integrated market that could one day perhaps rival the U.S. The new bonds are unlikely to hit the market until mid-2021 "at the earliest," according to Societe Generale's Jean-David Cirotteau. They'll come in a range of maturities and a 10-year benchmark rate somewhere between Germany and Italy, investors say. That means they'll probably add to the pile of negative-yielding debt (which topped $15 trillion this week, a 10-month high).  The impact of this week's agreement on financial markets was sweeping. Italian yields rallied, taking the 10-year back below 1% and narrowing the gap to their German peers to pre-crisis levels. An index of default risk for high-quality European companies fell to levels last seen in February, and those for high-grade and junk-rated U.S. corporate bonds dropped to the lowest in a month. The euro has strengthened to its best level versus the dollar since September 2018. Moreover, the plan has vaulted Europe up the ranks of its large developed-world peers in terms of a comprehensive response to the virus-related shock. As of writing, a trillion-dollar sequel to the U.S.'s pandemic relief package is still under heated debate, even as provisions that have been crucial to the recovery so far -- including jobless benefits and a moratorium on evictions -- are set to expire. .... And More Bad The Trump administration's unexpected decision to close the Chinese consulate in Houston nudged Treasury yields closer to fresh record lows. But on balance it rattled markets comparatively briefly. Investors are by now accustomed to this emerging new Cold War, and they have bigger ones to fear with a pandemic on the loose. As of this week, more than 4 million people in the U.S. have been infected with the virus. By way of retaliation, China ordered the U.S. to close its consulate in the southwestern city of Chengdu. But as our China Today writer Ye Xie points out, the market really only cares about the integrity of the preliminary U.S.-China trade deal, which so far is still being honored. The flare-up is a reminder, however, that the U.S. election is getting closer. "Investors appear to be content to allow the recent escalation to play out in the background with little challenge to present valuations. To a large extent, the market is heavily discounting the saber-rattling at this stage in light of the polls illustrating Biden's significant lead over Trump and all that implies for a transition in foreign policy in 2021," BMO Capital Markets' Ian Lyngen wrote this week, while adding a heavy dose of skepticism about said polls. Money managers on a Legg Mason panel discussion recently were more of the view the market simply isn't ready to price the implications of a Republican versus a Democratic victory in November. Investors will only start paying attention three months out, when the conventions are wrapped up and nominees confirmed, said ClearBridge Investments' Jeffrey Schulze. So those tea-leaf readings of the polls and long-shot takes on what the next administration will mean for the markets will have to wait until August... Beware August The Fed's massive intervention has crushed rates volatility. But what if it's only mostly dead*? The Treasury market has a history of reanimating at just the wrong moment for some big trades.  Analysis from Societe Generale's Michael Chang shows that since 2010, volatility in longer-dated rates has tended to swoon in July and rebound in August. That's a risk for traders who've moved out the curve to make money from the moribund market, such as an eye-catching short-volatility position in the 30-year Treasury this week.  It seems a sound trade with U.S. interest rates pinned near zero through at least 2022. But the horizon's strewn with event risk, including the possibility of further business shutdowns to handle the latest spikes in Covid-19 cases, and another massive U.S. fiscal package hanging in the balance. The stability of long-end rates will depend heavily on what the Fed does next. So far, its Treasuries purchases have removed more duration from the market than the government has added with a surge in borrowing since March. But that balance could shift with an expected increase in auction sizes, a move that may well be confirmed in the Treasury's refunding announcement on Aug. 5. That said, the Fed isn't likely to tolerate any significant weakening in rates that are highly connected to the real economy. While officials observed the customary public silence in the lead up to their July 28-29 meeting, a former colleague hinted policy is set to transition from firefighter-mode to healing the economy. "The Fed has indicated that they're going to shift their large-scale asset purchase programs from focusing on market function – which is now good – to focusing on how do you actually stimulate the economy. I think that does imply they're going to buy a greater proportion of longer-dated Treasuries," former New York Fed President Bill Dudley said on Bloomberg TV. And investor demand shouldn't be overlooked here. Buyers keep showing up for U.S. government debt -- this month's 10-year auction sold at a record-low yield of 0.65%. "Treasury bonds have been in an 'if you build it they will come' situation for a while now," said Atul Bhatia, fixed income strategist at RBC Wealth Management. "I think that supply can get absorbed." Forecasts for long-end yields are already ratcheting lower across the Street. JPMorgan strategists cut their year-end targets for the 10-year to 0.80% from 1%, and the 30-year to 1.65% from 1.85%. There's a decent case for yields to sink in the coming month, according to TD Securities' Priya Misra. She points out the 10-year benchmark has fallen in August in 22 of the past 35 years. History may not mean much in these interesting times, but it's fair to expect bigger price swings in holiday-thinned markets. Also, index extensions tend to be larger in August, drawing demand from benchmark-tracking portfolios. Another supporting argument for a reinvigorated Treasury market is the customary lull in supply of investment grade corporate bonds, which may herd more-conservative investors into government bonds. Early dealer calls for IG sales next month are in the $50 billion range, which would be the lowest August tally since 2015. Credit as `Cornerstone' That slide in supply is bullish for a market that's already got no shortage of cheerleaders. The average yield on high-grade U.S. corporate bonds slipped below 2% for the first time this week, according to the Bloomberg Barclays benchmark.  That's not great value for investors if you consider that the duration of that index -- its price sensitivity to fluctuations in interest rates -- is also the highest it's been in decades. Yet it's not hard to find people who are bullish on high-quality U.S. corporate bonds. Western Asset Management portfolio manager John Bellows put it like this in a recent webinar: There's more healing to come in the credit market, as spreads are still wider than they were prior to the crisis of the pandemic. Plus, "the facilities the Fed put in place are primarily designed to limit volatility in credit." Since its secondary market corporate credit facility launched in May, the central bank's demonstrated a willingness to calibrate purchases in line with spread movements, sending a message that it will escalate quickly if spreads moved significantly wider. Combining those notions -- that spreads still offer value; there's room for gains in a healing economy; and volatility is seen being low -- gives you a high Sharpe ratio, the holy grail of money management. "That should be interesting for every investor," Bellows said, and that's what makes IG unique and a "cornerstone" in portfolios right now. Small wonder that high-quality bonds have taken the lion's share of 14 straight weeks of inflows into global bond funds, according to EPFR. Not everyone's so enthused about this consensus, though. And some stats warrant attention in light of virus-related risks, or the possibility of a halt in the benefits that are keeping the U.S.'s economic engine of consumer demand running. Through the beginning of May, corporate bankruptcies were being filed at the fastest pace since 2009. Survival of the fittest is one thing, but that pain can permeate. Fallen angel rates -- or the pace of investment-grade companies sliding into junk territory -- have picked up sharply. More than a third of firms in the travel and leisure sector of a survey by financial data analytics firm Credit Benchmark have lost their IG status, and 23% of leisure goods companies. The recent declines in the Fed's balance sheet, which we discussed earlier this month, have also given some investors pause. That's mainly due to reduced dollar swap lines and Treasury lending facilities. But it's reasonable to assume that while the Fed remains committed to keeping those rates closest to the real economy -- benchmark rates for mortgages and lending to businesses -- at rock-bottom levels, it may soon get squeamish about directly stoking risky markets. These corporate credit measures are supposed to be temporary, after all: the Fed has pledged to put them away when they're no longer needed. Its enduring support for the world's biggest government market, meanwhile,is assured.

Bonus Points Awful news for savers and anyone trying to run a pension fund -- the collapse in real yields  Princeton's eviction lab is tracking an escalating crisis in U.S. homelessness Americans' aversion to mask-wearing Is holding back the economy Trump pick Judy Shelton edges closer to Fed Board, but she won't set the path of policy Former Fed official Narayana Kocherlakota lays out the case for the central bank to target racial inequality John Lewis, founding father. Argentina's debt chief takes on Wall Street. The average tenure for an economy minister in Argentina since 1983 is a year and a half *As Miracle Max would say. Speaking of which, this is the only way to remake the Princess Bride |

Post a Comment