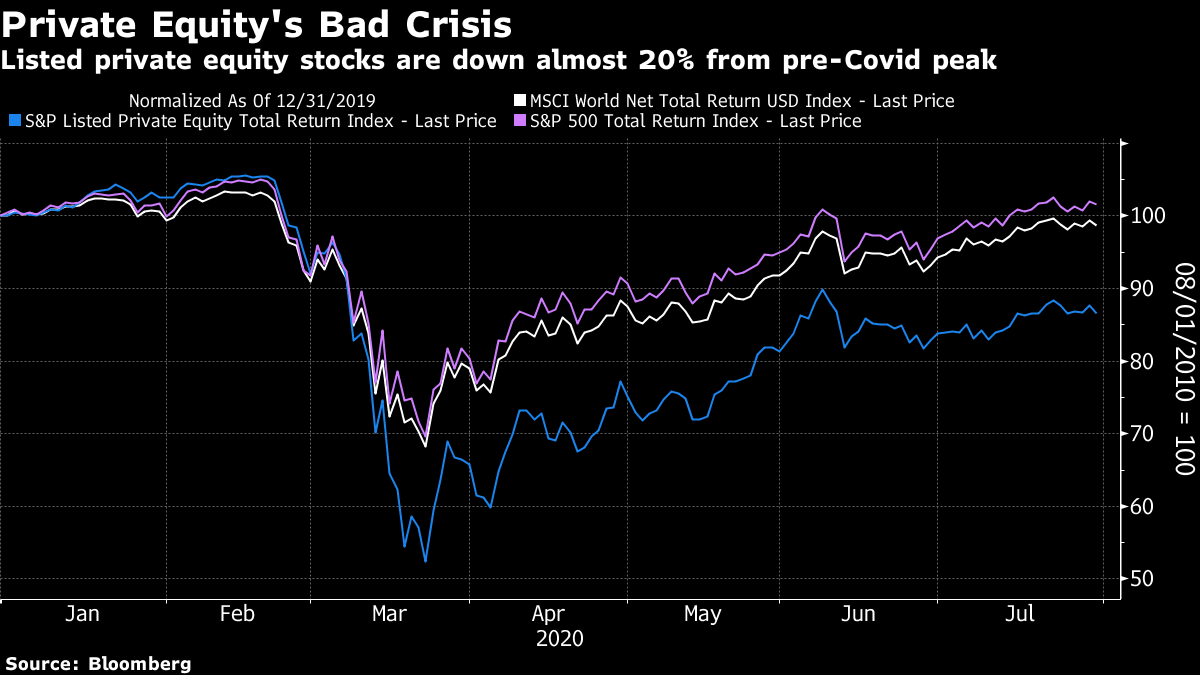

Barbarians With an Image Problem Few industries have an image problem like private equity. Thoroughly in the sights of late-night comedy liberals, private equity is seen as the ultimate expression of all that is wrong with the concept of shareholder value. The popular narrative is that leveraged buyouts allow private equity operators to strip assets, cut staff and move on having pocketed the value. One recent headline in satirical website The Onion proclaimed: ""Protesters Criticized For Looting Businesses Without Forming Private Equity Firm First." Looking at the share price performance of private equity companies, it does appear as though the sector has had a bad crisis. S&P's global private equity index is dominated by U.S. companies, along with a number of Guernsey- and Jersey-listed firms; 50 of the 64 members are either in the U.S. or the British Isles. If we take the S&P 500 as a benchmark, it has lagged behind, though it has done significantly better than the MSCI World over the last decade.  On either basis, however, listed private equity has had a bad crisis:  It's surprising that listed private equity hasn't performed better for shareholders, given the profound effect the companies have had on the economy and equity markets. These statistics come from a Committee on Capital Markets Regulation report on the impact of private equity buyouts on productivity and jobs: private equity-backed U.S. companies numbered approximately 4,000 in 2006, but by 2018, that figure had doubled to about 8,000. Meanwhile, the number of publicly traded firms in the United States fell by 14 percent, from 5,113 to 4,397. Globally, private equity's net asset value has jumped more than seven fold from 2000 to 2018, while the market capitalization of the public equity market grew only 2.1 times over the same period. Private equity has been at the center of a "great shrink" in public equity markets over the last two decades. Has it paid off for investors and for the economy? On the first question, I recommend this great read from BusinessWeek on Ludovic Phalippou, an Oxford University academic who has devoted much of his life to attacking the returns generated by private equity. His thesis is that the industry serves primarily to enrich private equity executives through excessive fees. What is apparently his final paper on the subject can be found here, and it is worth reading. If they have ripped off the institutional investors entrusting money with them, that is a serious charge. It means that they have ultimately ripped off pensioners. But for now, let's focus on the most popular charge — that they are merely looters who slash costs and cut jobs without helping to build the economy. The committee's report shows that the case is weaker than it appears.

A survey of the academic literature over the last 20 years, covering the U.S. and Europe, shows that buyouts do improve productivity, and not just by cutting jobs, which tend to rise when privately held companies are taken over. The main source of improvement comes from privately owned firms that were relatively unproductive in the first place. So the notion that private equity acts as a discipline and a force for improvement on managers does seem to stand.

The picture on jobs, the most emotive charge, is less clear. Studies generally find that private equity buyouts in the U.S. can lead to slightly positive effects on employment when closely held companies are bought out; but that buyouts of public companies, which tend to be bigger, lead to job losses. This is a key finding from the most recent study on U.S. public equity: the buyout of public firms (constituting 14% of transactions) is associated with a 10 percentage point decline in job growth and the buyout of single divisions of a firm (constituting 13% of transactions) is associated with a 16 percentage point decline. These declines are 12.6 percentage points and 11.4 percentage points, respectively, when acquisitions and divestitures are included. However, due to the larger number of jobs at public companies, the study finds that job growth at target firms excluding the effects of post-buyout acquisitions and divestitures is 4.4 percentage points lower relative to peers over the two post-buyout years. In Europe, private equity seems to be a job-creator. The most recent study cited in the report looks at 1,580 buyouts between 1992 and 2017 in European countries, as well as former Soviet republics, the Middle East and North Africa, and found that target firms enjoyed a statistically significant job increase of 26% compared to peers while they were held by private equity.

The report's main takeaways seem to me to be that buyouts of big public companies, the kind that garner the most publicity, are the least successful and justifiable. Events like the buyout of RJR Nabisco, unforgettably chronicled in "Barbarians at the Gate," don't happen often; but it does look as though investors with private equity groups could do with telling the managers running their money not to bite off more than they can chew. In Europe, where inefficiently run companies tend to be easier to find than in the U.S., it looks as though the industry's bad image is undeserved.

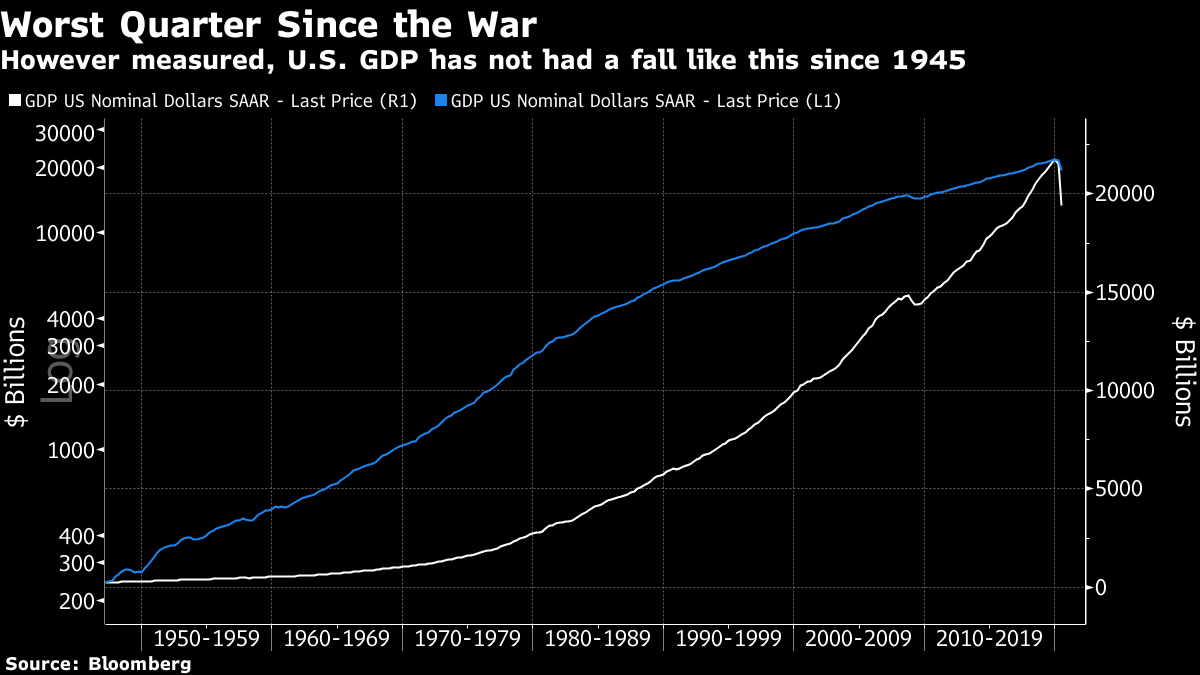

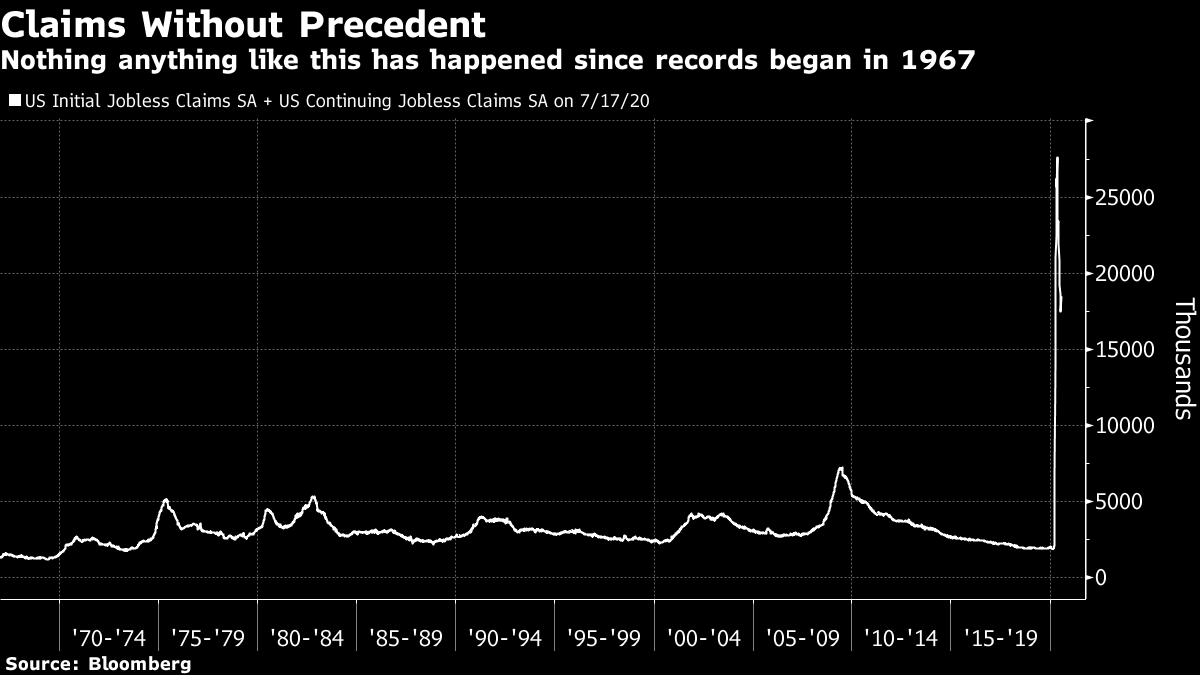

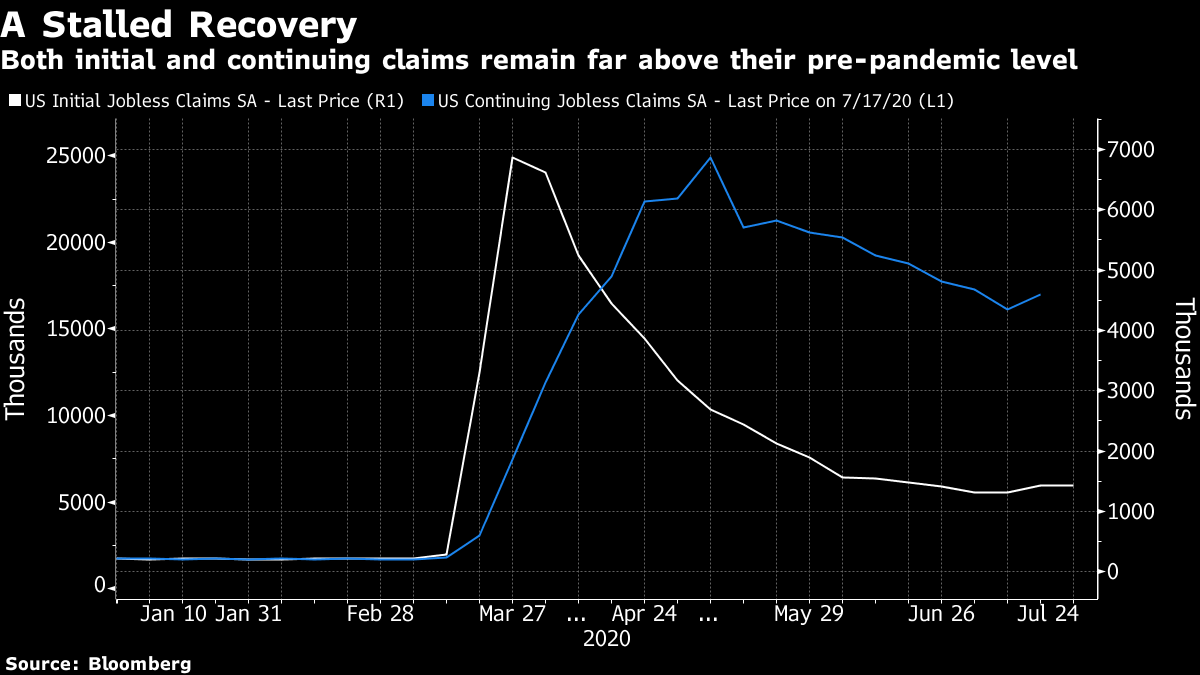

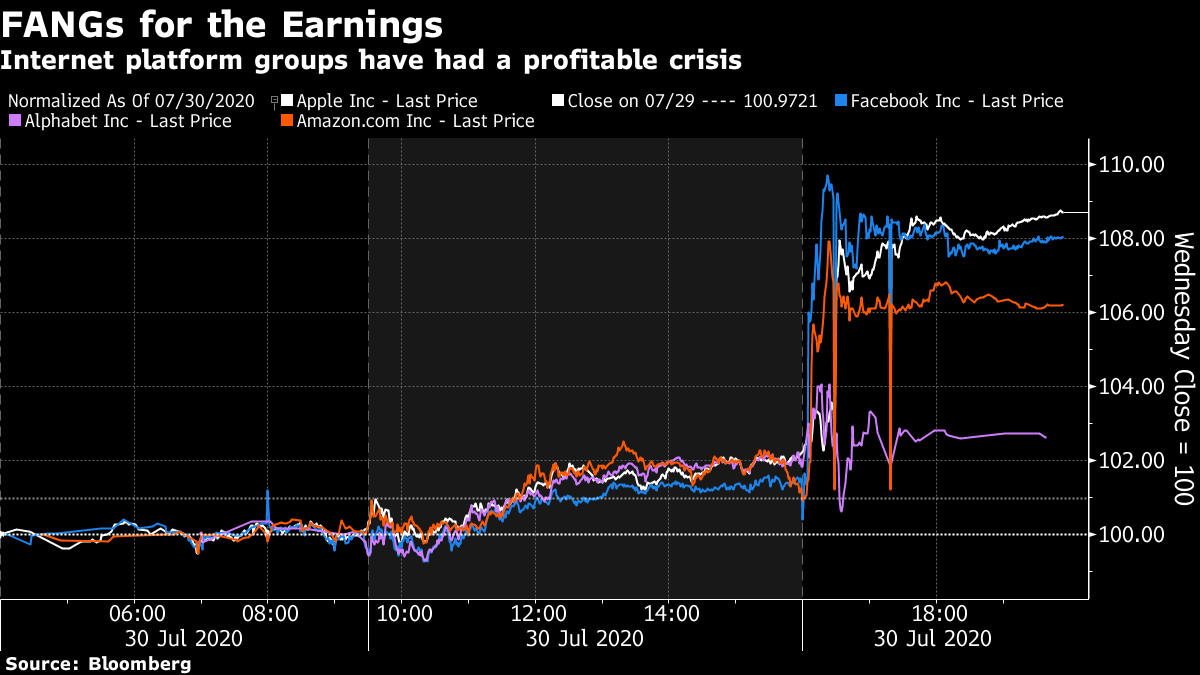

Shock! Horror! GDP! It's possible to exaggerate the awfulness of the U.S. second-quarter GDP figures, but it's not easy. The annualized rate of 32.9%, which is most popularly quoted, is the number that would apply if the economy continued shrinking at the same pace for four quarters in a row. The economy hasn't just declined by a third. That said, it remains true, as the following chart demonstrates on both a linear and log scale, that this is the worst decline the U.S. economy has suffered since World War II:  The loss of jobs that followed the Covid outbreak has taken the economy into uncharted territory, and it behooves all of us to accept that. Thursday also brought news on continuing and initial jobless claims, the most immediate measure of employment trends. Again, what has happened this year is so far out of proportion with anything in the prior half century that it isn't clear any precedents are truly relevant:  I've combined both initial and continuing claims to give the most complete picture possible. This chart looks like Armageddon, and the effects on many other economic measures have been nothing like so sweeping. Again admitting to humility with so few precedents to guide us, I would suggest this shows that government support for those who lost jobs due to Covid-19 has had a very significant effect in cushioning the damage. As Bloomberg Opinion columnist Mohamed El-Erian says elsewhere, these numbers ram home that Congress is playing a dangerous game as it tries to decide how to extend that support, which is scheduled to end Saturday. The trend is unmistakably growing worse again. Here are continuing and initial claims, on separate scales, for the year so far:  There will be a heavy price to pay for this pandemic. Congress's nervousness about increasing the price tag is understandable. But these numbers suggest that some kind of continued support is vital. Even without precedents, that seems hard to deny. FANGs and Profits The FANGs are more than an acronym. This quarter, four of the planet's five largest companies by market cap have taken to doing things together. On Wednesday, their CEOs faced Congress. Then on Thursday, after the market closed in New York, all four released second-quarter results. Going before Congress was uncomfortable but they avoided any serious damage. Judging by the way their share prices performed in after-market trading, the earnings announcements were much more comfortable:  There is plenty of material elsewhere on Bloomberg to help analyse how they did it. And it is always possible that some will take the opportunity to "sell on the news" in the days ahead. The bottom line is that all these companies found ways to flourish during the worst of Covid-19, to a much greater extent than even Wall Street had hoped. It was a remarkable achievement for a group of well-run companies with great business models. The risk at this point is primarily political. As the congressional hearing demonstrated, there are people at every point of the political spectrum who have reason to dislike the FANGs. There are also some obvious ways for antitrust authorities to enforce more competition — splitting Instagram and WhatsApp from Facebook Inc., for instance. Can they persuade politicians and the electorate that other companies have a fair chance to compete, and that they aren't damaging the economy? These great results, especially when achieved at a historically awful time for the economy, will make that job that much harder. Survival Tips New York's slow reopening meant that I was able to have an acupuncture appointment for the first time since the virus arrived. It sounds so unappealing to lie on a bed with needles sticking out of you, but it does help to relax like nothing else I have ever tried. For those who don't balk at the sight of needles, it's worth a try. Have a good weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment