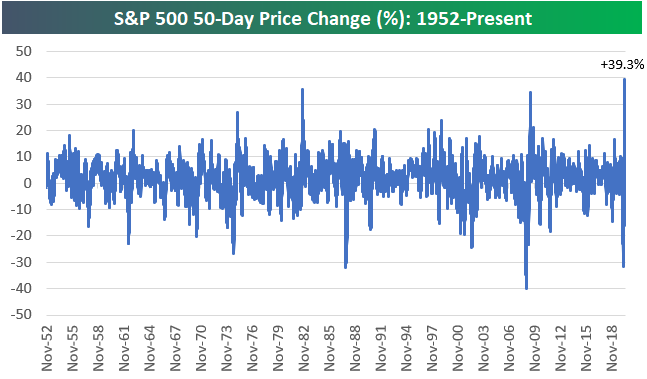

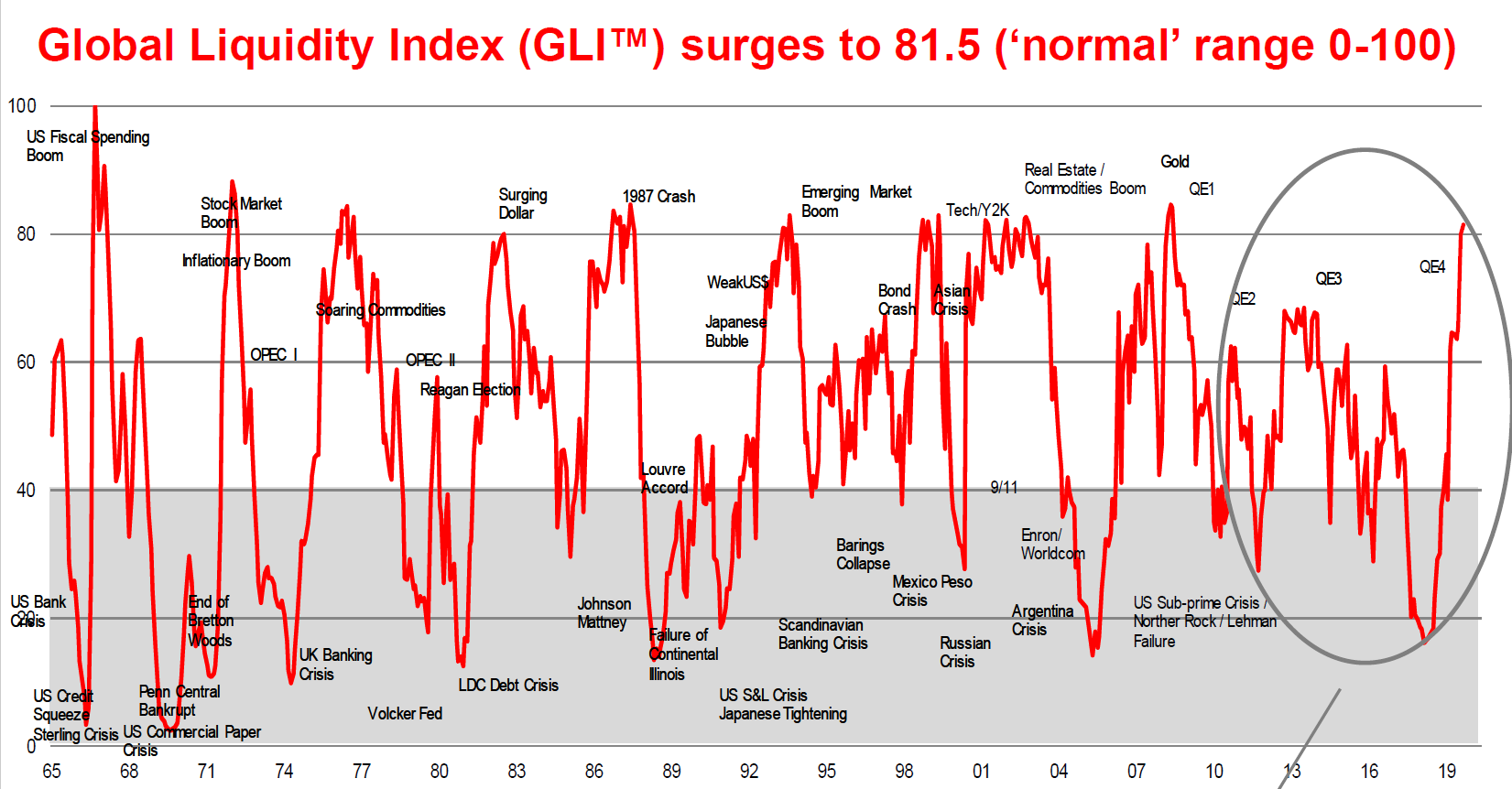

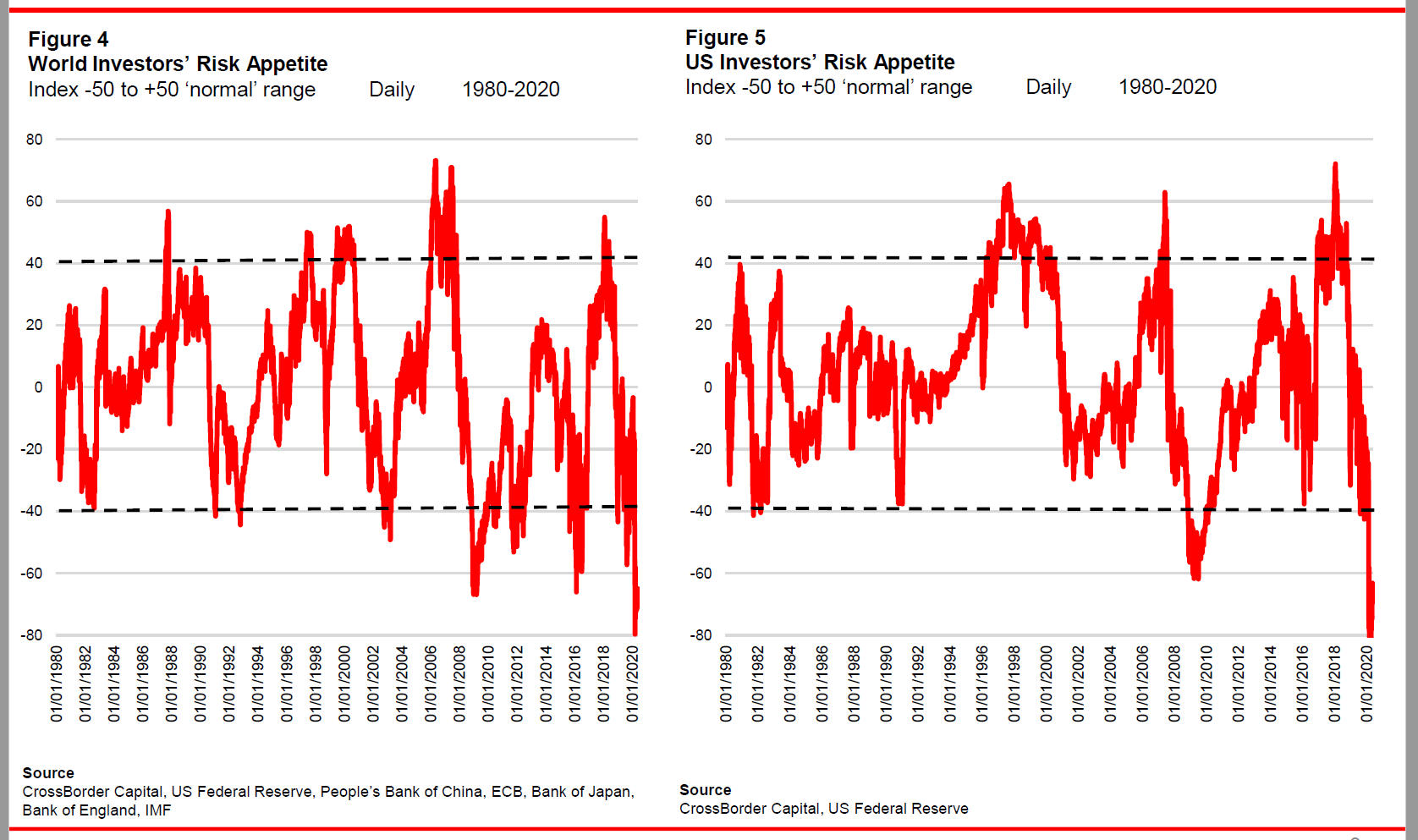

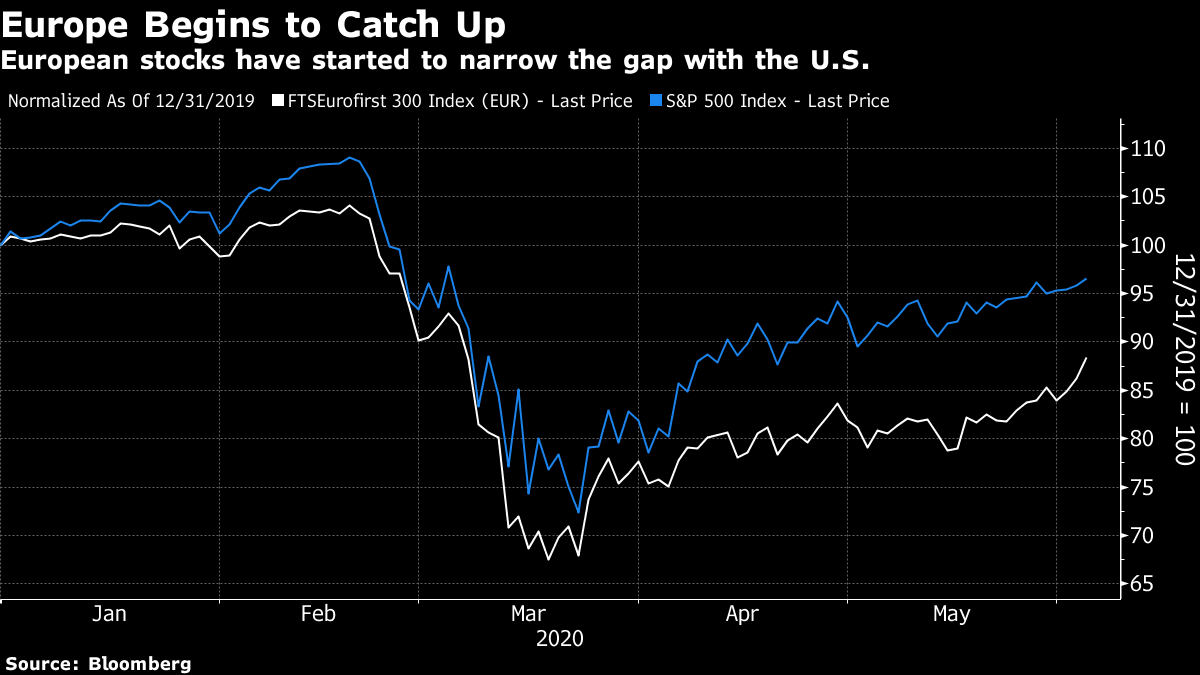

Follow the Money…. The rally now under way in global stock markets isn't just the most hated in history, as I suggested earlier this week. It is also the biggest 50-day rally on record. The March low for the S&P 500 is now exactly 50 trading days ago, and the total percentage gain since then is the best 50-day stretch in the history of the index, as shown here by Bespoke Investment Group:  Before 1952, the market also traded over weekends, so comparisons are difficult before then. But there's a fair chance this is the strongest rally ever. The two previous strongest 50-day rallies, in 2009 and 1982, both came after major lows, and were followed by long bull markets. The last four months — encompassing the market's pre-Covid peak and its monthlong nose dive — have been unlike anything seen before. Like seemingly everything else in life these days, reactions to the rally are polarized. Feedback I have had splits roughly 50/50 between inveighing against the insanity of markets and their utter disregard for the disastrous world around them, and total confidence that this is all down to central bank intervention, and that a rally was inevitable as soon as the Federal Reserve made it clear that it was going for broke. People feel strongly about this because it juxtaposes so sharply with scenes of mayhem on the streets and sickness outside. Markets are ignoring reality, and haven't noticed how terrible the world is, and so on. In the long term, there are risks in a rally like this while many suffer. Worsening inequality has been the dominant narrative in the Western world for the last two decades. It deepened sharply after the last crisis. The long-term effects for social cohesion if inequality grows even wider after this crisis don't bear thinking about. In the shorter term, the most cogent explanation is that we should all have followed the money. The release of liquidity by the Fed, announced at the beginning of the day on March 23 when the market would hit bottom by the close, has been unprecedented. This is how Points of Return started on that day: These are extraordinary times. The Federal Reserve opened the week with a package of measures to support the market so drastic that Jim Bianco, head of Bianco Research and a Bloomberg Opinion contributor, commented: "At first blush, it looks like they are nationalizing financial markets, except for equities and high yield. This better work in stabilizing financial markets!" And yet U.S. stocks finished down for the day, as did bond yields, in part because of continuing Congressional drama that saw the Democrats continue to play a risky game and block a $2 trillion fiscal package. By the end of the day, Britain had been put under lockdown for three weeks. In one item of good news, the increase in the Italian death rate appears to be declining. Meanwhile, Spain appears to be entering its own nightmare. Now, of course, I can see that it should have started: "Hey everyone, the bottom is in! Fill your boots!" I apologize for the omission. In hindsight, we can also see that liquidity from the Fed (and other central banks) was the crucial variable. If the Fed is nationalizing financial markets, to use Bianco's emotive term, we should expect it to have an effect. We can illustrate this with graphics from CrossBorder Capital in London that measure excess liquidity in the global financial system. According to CrossBorder's index of global liquidity, the world was awash by the end of April — when it called for a "V-shaped" recovery, based on the availability of money and the fact that capital would remain intact to a far greater extent than after previous major shocks. This is how global liquidity has moved over the last four decades on CrossBorder's definition:  The last time the world was flooded with liquidity was in 2009, which was also the last time we saw a rally in the stock market on anything like this scale. Alternatively, if we look at risk appetite, which CrossBorder measures quantitatively by looking at the proportion of "safe" assets — government bonds and cash — to risk assets, we see that we hit a remarkable low for risk appetite earlier this year, more or less guaranteeing that some of the money earning no interest in cash or cash-like investments would have to find a new home:  This measure of risk appetite, note, is directly affected by the release of liquidity by central banks. And as risk appetite had been brought to such a historic low, a rubber band-like trajectory for stocks was almost guaranteed. It may not be quite this simple. If every metropolitan area in the U.S. had suffered as badly from the virus as New York did, which was a perfectly plausible scenario 50 trading days ago, the economic damage would have been that much deeper and animal spirits might have been so bad as to counteract the rush of money. But the pandemic hasn't fulfilled the worst fears, and the Fed has been impossible to deny. Meanwhile, in Europe…. Thursday will see a meeting of the European Central Bank, where there is now a firm expectation that more quantitative easing will be announced. While the ECB's balance sheet has expanded dramatically this year, it is dwarfed by the Fed. That should make it easier politically for the ECB to continue its dovish course. Also, there are some reasons to be cheerful about Europe. The effort to start a common EU-wide borrowing program, to help deal with the after-effects of the coronavirus, continues apace, with support from the leading political players. Meanwhile, Germany really does appear to be set on trying a more expansive fiscal policy. The $146 billion plan agreed by Chancellor Angela Merkel's coalition has somehow exceeded optimistic expectations by 30%. German fiscal expansion plus a common fiscal policy are the two moves that investors have long demanded to deal with the structural imbalances at the heart of the euro zone. And we can see what looks like the beginning of a turn in European fortunes. The FTSE-Eurofirst euro zone banks index has rallied by 31.5% since its low on April 21. It remains in a deep hole but this is encouraging. European stocks have outperformed the U.S. for the last couple of weeks, narrowing what had been a wide gap.  And the euro is looking stronger, helped by the money exiting the safety of the U.S. as risk appetite returns. A stronger euro could be a problem in the longer term, but for the moment it is a symptom that confidence in the euro zone is returning:  It may just be possible that the Covid-19 crisis will go down in history as the shock that forced the euro zone to get its act together, rather than the final moment that brought an over-ambitious project in monetary and political engineering to an end. With optimism plainly now high, the ECB will need to be careful to avoid disappointment. Survival Tips Live music is back in London. If you go to the Wigmore Hall's website, you get details of livestreaming concerts that are being held in London's most intimate classical music venue. It's a great place to hear live solo and chamber music, and the acoustics are superlative. Nicholas Daniel, like Stephen Hough who gave the first of these concerts, was a BBC Young Musician of the Year many years ago, so talent continues to win out. The concerts will take place in an empty hall, and the lack of bodies might affect those acoustics. Lowering the tone a little, it does remind me a classic Bryan Adams video. But if you tune in, you will know you are listening to a live performance. And there is something very proud and slightly British about performing to an empty hall, rather than just livestreaming a recording of an old performance. Good for them. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment