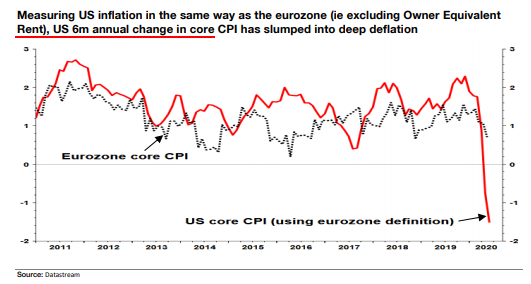

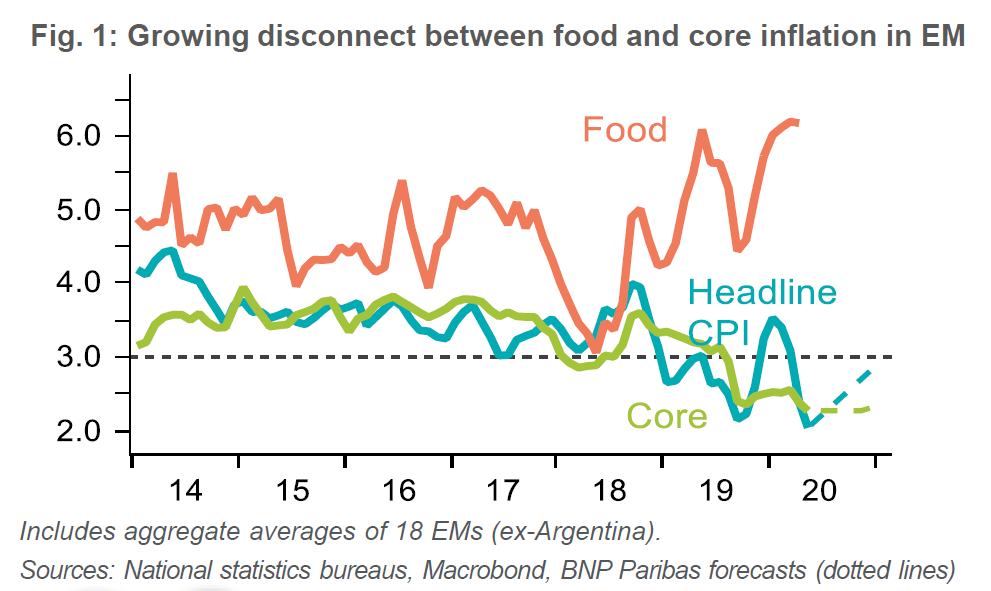

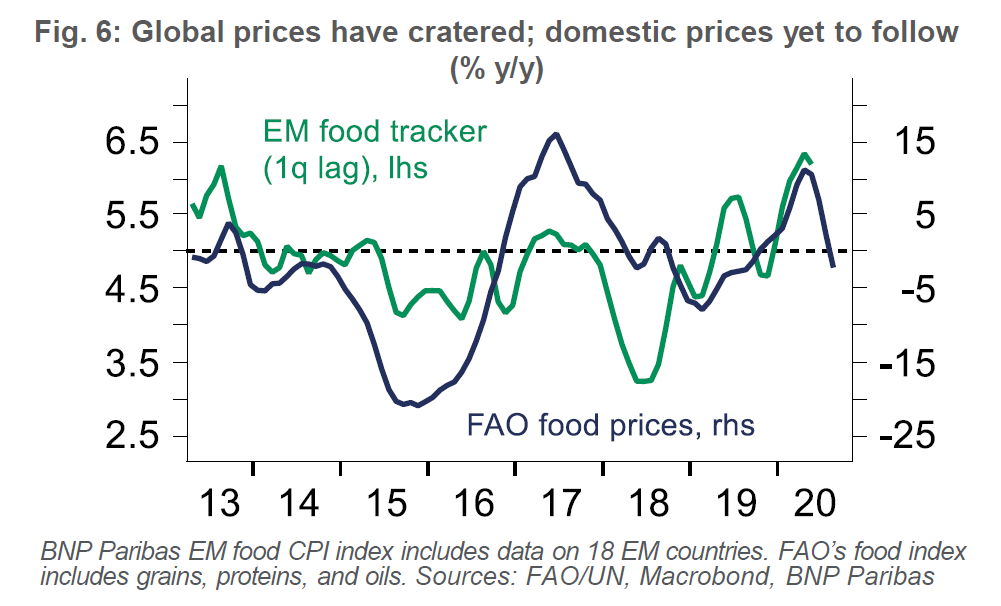

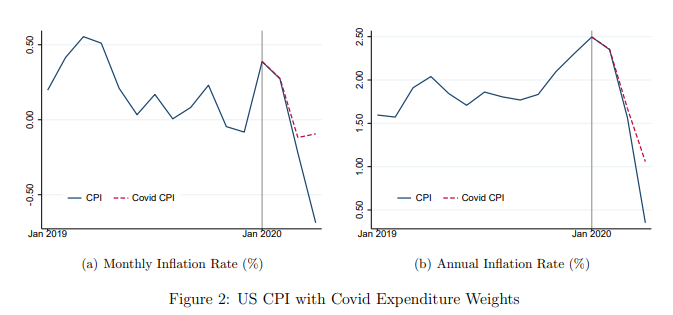

Lead Us Not Into Inflation The world is in a deflationary dive. There is no chance of a significant resurgence in inflation this year. But there is every chance that we will see it return not long thereafter. Inflation is one of the very few things that it is still cheap to hedge in financial markets. Therefore, this might be a good idea. Let me take you through the pictorial reasoning to get to that conclusion. At present, markets are recovering from a deflation scare (with the exception of Japan where deflation is less of a scare and more a way of life) but still point to very low inflation for a decade ahead (with the exception of the U.K. which has had more of an endemic inflation problem than the rest of the developed world ever since the last global financial crisis):  In the short term, this is obviously correct. The immediate impact of the sudden stop in economic activity that accompanied the Covid-19 pandemic was self-evidently deflationary. As Albert Edwards of Societe Generale SA points out in this chart, core inflation in the U.S. would now actually be negative, if the country's counter-intuitive method for calculating the change in housing costs were replaced with the definition used by the euro zone:  Meanwhile, the impact on emerging markets has also been deflationary. As this chart from BNP Paribas SA shows, headline and core inflation (excluding volatile fuel and food costs) had been declining steadily for a while in the emerging world. Headline figures were kept aloft by rising food prices:  However, if we look at the global prices of basic foodstuffs, as collated by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, we see that they have tanked as the pandemic has taken hold. That isn't yet reflected in domestic prices, and more or less ensures that headline inflation will remain very low for the remainder of the year:  So markets are positioned for deflation, and in the very short term they are right. But after that it begins to get more complicated. The Covid-19 lockdowns have changed consumption patterns, and the goods that are being consumed more have started to gain in price. The following chart, taken from a research paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research by Alberto Cavallo of Harvard University, shows what U.S. inflation numbers would look like if the basket of goods used to calculate it were adjusted to reflect what consumers are actually buying.  This is concerning research as it suggests that "the cost of living for the average consumer is higher than implied by the official CPI. The welfare implications are particularly relevant for people losing their jobs" during the pandemic. In other words, it looks nastily as though the effect of differential inflation in goods will have served to increase inequality still further. It also suggests that inflationary pressures are greater than they seem. If we look at supplier delivery times, they have also been affected by the pandemic, as might be expected. As this chart from CrossBorder Capital of London shows, longer delivery times have a history of being followed by higher inflation. The strong implication, again, is that there is basic inflationary pressure in the pipeline, even if hasn't made itself felt yet.  While market expectations remain contained, there is also a surprisingly sharp increase in inflation expectations by consumers (which might reflect their experience of paying more for the goods they are buying most during the lockdown). As this chart from the New York Federal Reserve shows, expectations have picked up noticeably, and are widely dispersed:  Despite the deflationary impact of the pandemic there is a sound logical reason to fear inflation, which is the immense rise in world money supply, illustrated in this chart from TS Lombard:  Naturally the Fed is leading the way, and recent comments from its chairman, Jerome Powell, have been taken as confirmation that it is prepared to take the risk of raising inflation. The rise in the size of the balance sheet since the Covid-19 crisis began is fully comparable with the rise after the first global financial crisis:  As London's Longview Economics points out, the money from the Fed is also, critically, having an impact on credit conditions. The last three months have seen a significant tightening in the spreads at which very low quality CCC-rated debt trades, compared to Treasury bonds. This implies a long-term risk of continued malinvestment caused by the survival of "zombie" companies, but it also implies that the Fed's money is finding its way into the economic bloodstream.  There were widespread predictions of inflation after the Fed's crisis measures in 2008 and 2009. It didn't come to pass. But there are some significant differences this time. Perhaps most importantly, as demonstrated in this chart from INTL FCStone Inc.'s strategist Vincent Deluard, the personal savings rate has shot up in the U.S., along with balances in money market funds. There was no behavior like this a decade ago. That money remains ready to find a home, and the issuance of more Treasury debt and more easy monetary policy from the Fed will likely increase the incentives to place it in the stock market, or spend it:  With the Fed likely to hold rates low, the logical way to ease the pressure in the system, as all the liquidity finds a home, will be through rising prices. This is true even though the immediate effects of the crisis have seen extreme deflationary pressure. That suggests that it would be a good idea to hedge against inflation. As this chart from Michael Gourd and Michael Crook of UBS Group AG shows, uncertainty remains high, with the result that the cost of hedging a range of asset classes remains close to its highest levels of the last 10 years. The big exception is inflation where the market is pricing about 1.2% for the next decade. It's cheap to bet that inflation will be a bit higher than that in the years between now and 2030.  And if you don't want to use breakevens, Deluard suggests that there could be opportunities in Latin American currencies. All emerging market currencies have had a torrid time of late, and would be greatly relieved by a return of inflation in the U.S. This is particularly true of Latin American currencies. As JPMorgan Chase & Co. shows, they have been bid down savagely against the dollar over the last decade, and have fallen by as much as 20% even in real terms:  There are plenty of reasons to be nervous about Latin American currencies at present, of course. But they have conspired to make the Mexican peso, the Brazilian real and the rest into cheap inflation hedges. When hedging is this cheap, and when a return of inflation could cause so many plans to go awry, it seems silly not to take the market up on its offer. Survival Tips That now completes three months of writing daily market newsletters sitting in my Manhattan bedroom. I would like to nominate this song, with a wonderful video set in New York, as the theme song for these very strange times. It's by another Englishman in New York, also called John, and the chorus is perfect: "Nobody told me there'd be days like these." Strange days indeed. Have a good weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

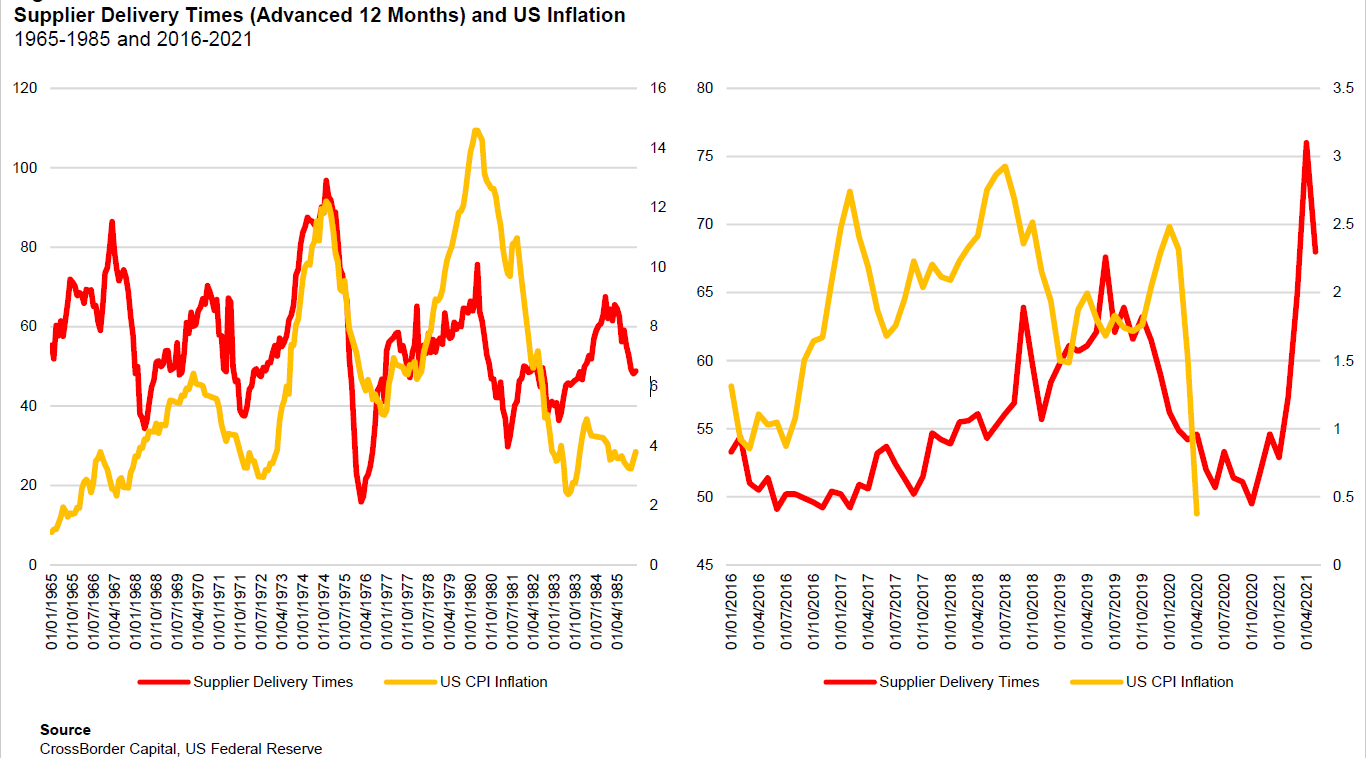

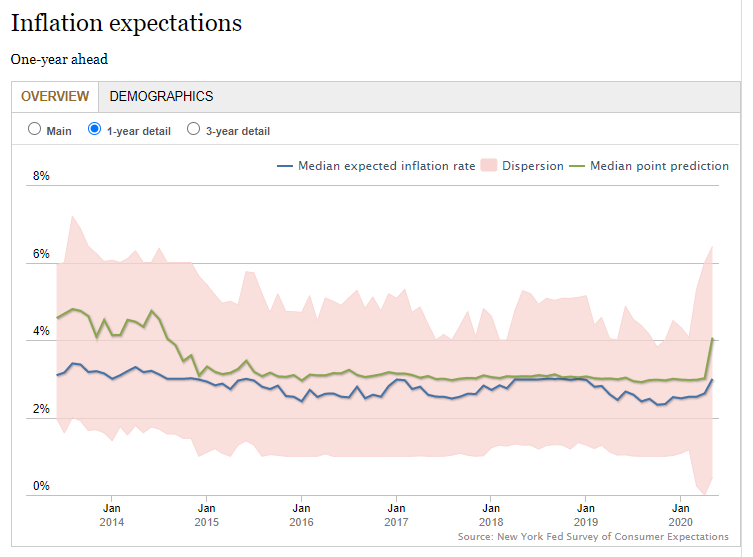

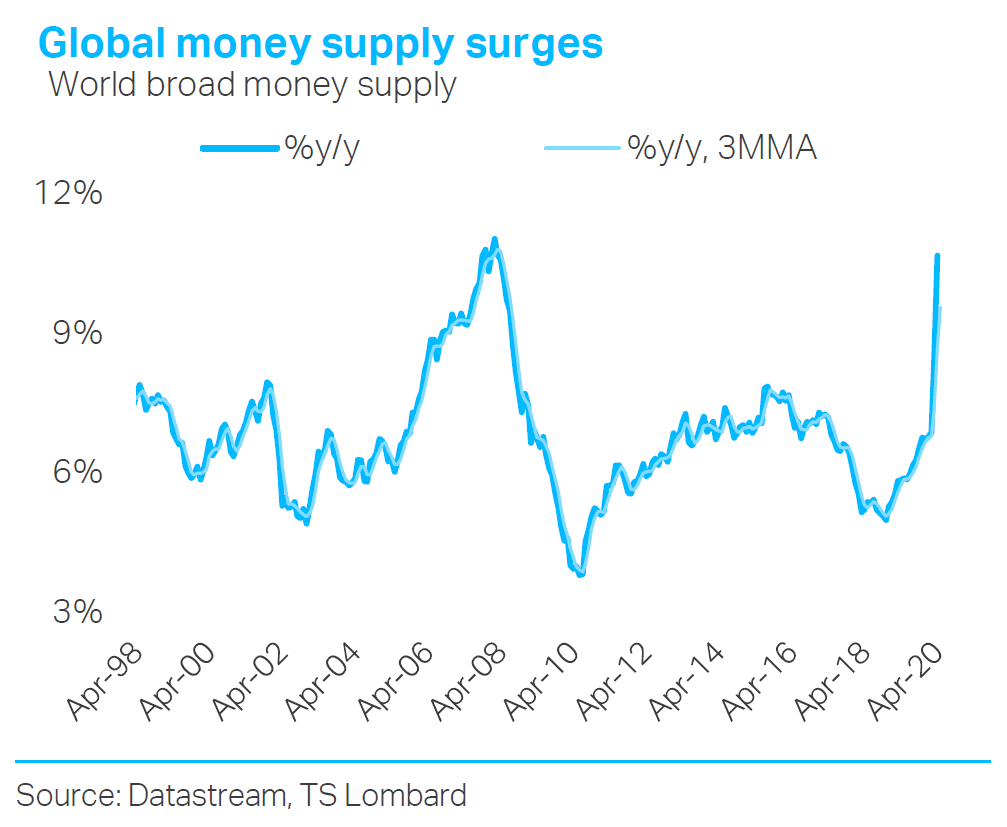

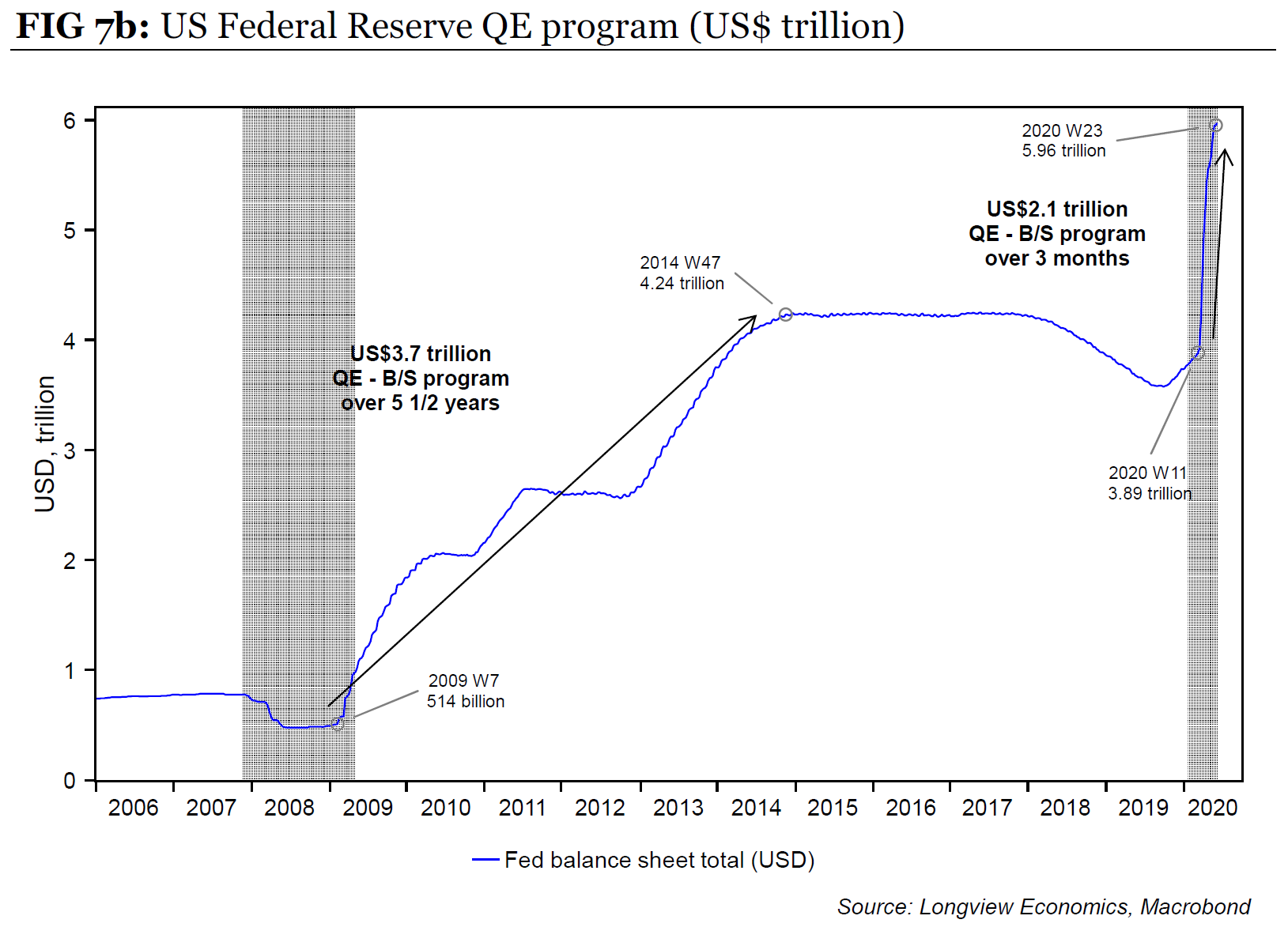

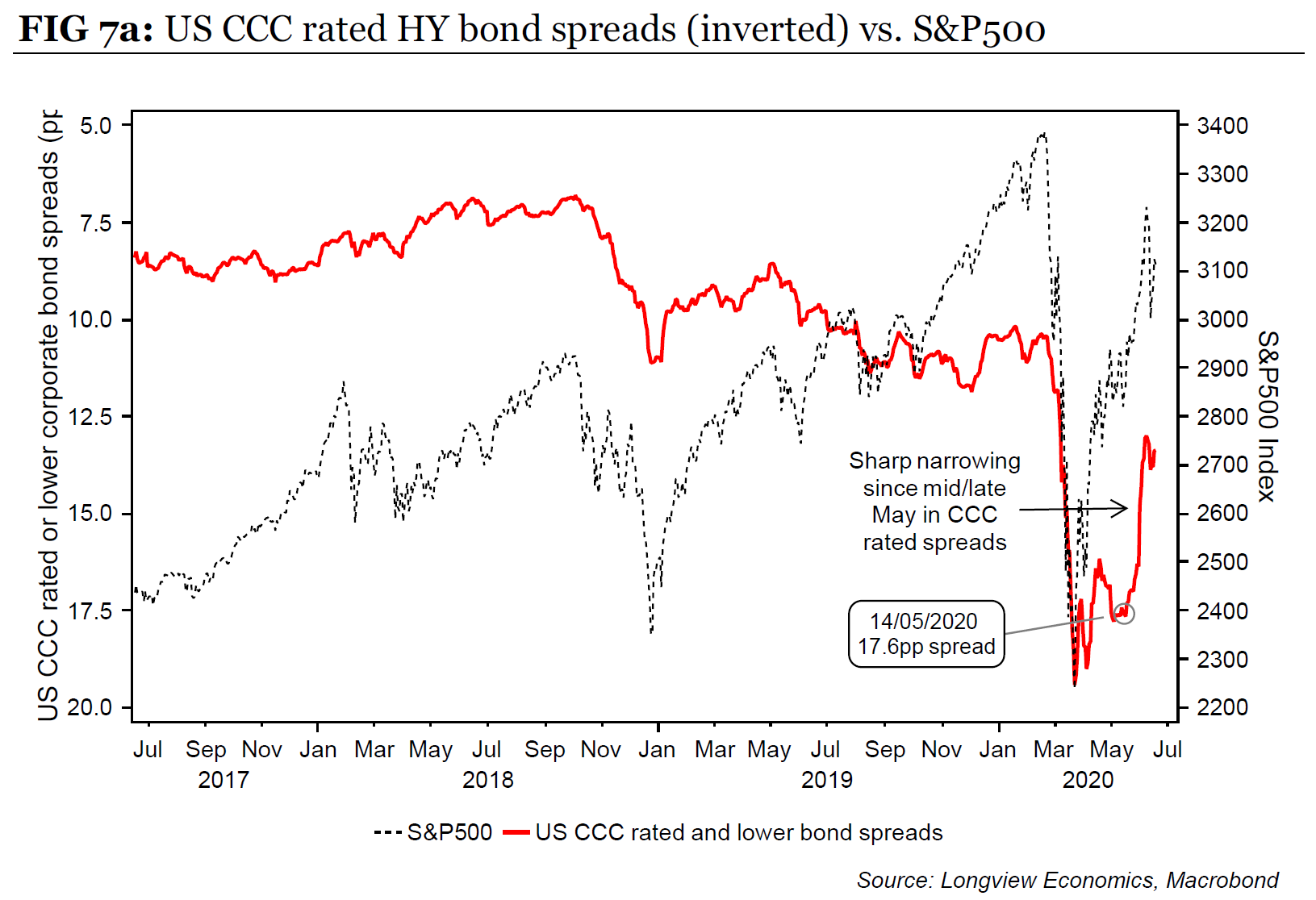

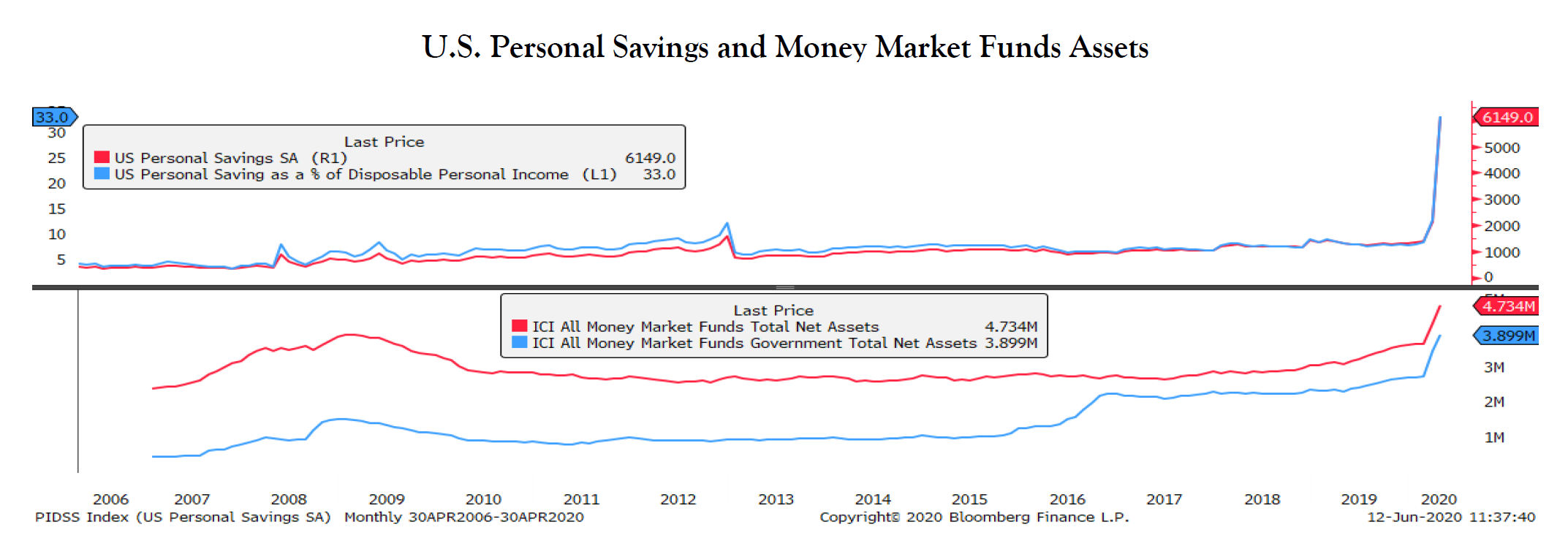

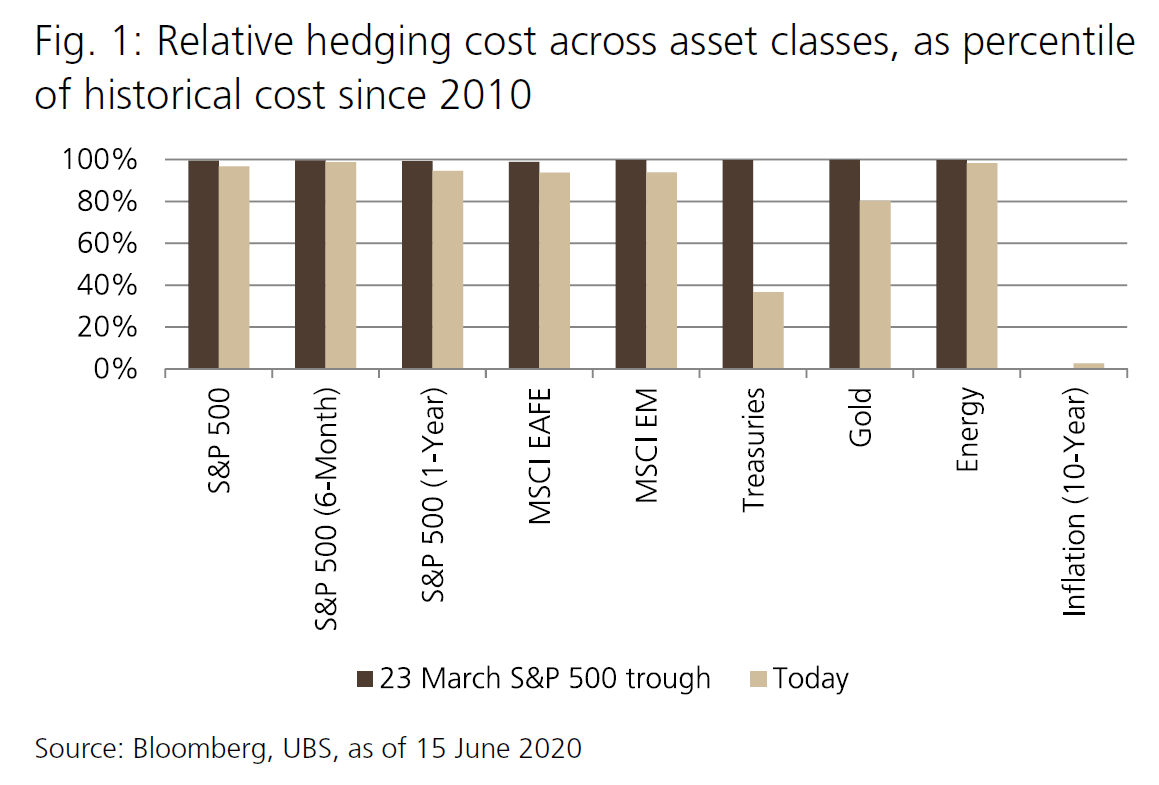

Post a Comment